8.1 A forest is more than just its trees

| CHAPTER 8 | COMMUNITY ECOLOGY |

BRINGING A FOREST BACK FROM THE BRINK

128

129

CORE MESSAGE

Ecological communities are complex assemblages of all the different species that can potentially interact in an area. All the pieces of the ecological community are connected; change one thing and many others are affected. This means ecosystems are often negatively affected by human impact. Understanding the interconnections within the communities may allow us to better protect and even help restore damaged ecosystems.

Guiding questions

After reading this chapter, you should be able to answer the following questions:

How do matter and energy move through ecological communities?

How do matter and energy move through ecological communities? How do biotic and abiotic factors affect community composition, structure, and function?

How do biotic and abiotic factors affect community composition, structure, and function? How do species interactions contribute to the overall viability of the community?

How do species interactions contribute to the overall viability of the community? In what ways do human actions affect ecological communities and how can we take steps to help restore damaged ecosystems?

In what ways do human actions affect ecological communities and how can we take steps to help restore damaged ecosystems? How do ecosystems change over time through ecological succession? How can we use this knowledge to assist in ecosystem restoration?

How do ecosystems change over time through ecological succession? How can we use this knowledge to assist in ecosystem restoration?

130

Recently, conservation biologist Josh Noseworthy and a friend decided to take a winter hike through New Brunswick to Ayers Lake, one of the most pristine places in the world. To get there, they had to walk up a long forest road, which seemed to take forever—in part, because the scenery was so depressing. All they could see were the same types of trees—the same height, width, and age. It was hard evidence that this land had once been stripped by lumber companies harvesting trees, mostly for construction or paper, which were then replaced with row upon row of the same type of species, all planted at the same time. There was nothing natural about this silent forest; the only colours were the dark trunks of the monotonic trees, separated by starkly white, snowy spaces that reflected the bright sunlight that forced the hikers to occasionally squint to see. Finally, after what seemed like an interminable climb, Noseworthy came to the top of a hill, looked down at the vista below, and exhaled. This, he thought, is what a forest should look like.

Below him lay one of the last remaining parts of a crucial ecosystem known as the Acadian forest. The difference between what they had just passed through and what lay before them was remarkable. To descend into the Acadian forest, Noseworthy and his fellow hiker had to carefully make their way through the thick, diverse vegetation, winding their way around trees of all shapes and sizes. After being in the bright sunlight, it took their eyes a while to adjust to the darkness of the native forest, where tall trees create a canopy that barely lets any light through. They passed through a massive, dense stand of trees whose cavities would house the spring nests of birds or squirrels—the same species that help disperse the trees’ seeds. They stepped over huge, moss-covered fallen trunks that were slowly decaying and replenishing the soil, while serving as rich habitat for invertebrate communities that recycle the trees’ nutrients, and the elusive salamanders that feed on the worms and insects. It was winter, so the forest was relatively quiet, but in the spring it would come to life with the multi-layered calls of different species of birds, the chatter of squirrels, and the rhythmic carpentry of the woodpecker.

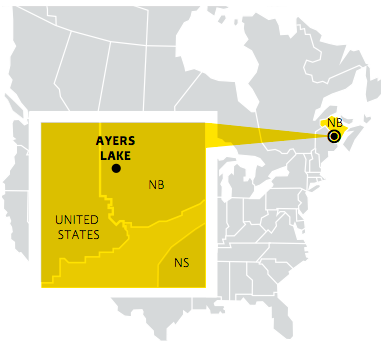

Finally, using the shards of light penetrating the treetops to deftly navigate through the diverse vegetation, the hikers reached Ayers Lake, one of the few remaining water bodies without a single cottage, farm, or humanmade structure alongside it. The sight made Noseworthy, a conservation biologist at Nature Conservancy Canada (NCC), stop in his tracks. “It was really quite an experience for me to see a lake surrounded by only forest,” he says. “I’ve read about the lake for years, and been to many Acadian forests before, but never one that had not been altered by human activity in some way.” That’s because less than 5% of the Acadian forest remains in its natural state.

WHERE IS AYERS LAKE?

131