8.2 All the pieces of the ecological community puzzle are connected

In the years before Europeans settled in the Maritimes, as much as 50% of the land was covered in Acadian forest—a highly diverse ecosystem made up of many plant, animal, and fungal species, not to mention the millions of species of bacteria that inhabit the soil. These forests, found throughout southeastern Canada and the northeastern United States, provided vital functions. These include serving as habitat for innumerable species, providing a natural sink for carbon dioxide that helps regulate climate, and creating a dense root network that pulls up thousands of litres of water per day in the summertime, contributing to the forest’s humidity levels and its rainfall. These roots also provide other benefits: they protect surface waters by reducing the flow of sediments into nearby streams during rainstorms, allowing the water to soak into the ground to replenish groundwater supplies. (See Chapter 11 for more on the services forests provide.)

But once Western settlers arrived, they quickly began clearing the land to create farms and harvest timber. Where sections of the forest remained, lumber companies began to remove the trees they needed (hardwood for paper, softwood for lumber). If they could work around the remaining species, these less desirable trees were left behind; if not, everything was removed. Companies then replanted species that grew the fastest, such as spruce trees, so they could be reharvested as quickly as possible. Now, only pockets of the natural Acadian forest remain, mostly in small, isolated areas surrounded by steep gorges that make them inaccessible to harvesting, such as the area around Ayers Lake.

Since so little of the Acadian forest remains untouched, some of its characteristics are somewhat hard to determine. In general, a healthy Acadian forest has a mix of 30 or so different species of trees, living interdependently with associated plants and animals. The well-being of any one of those species depends on the health of the entire ecosystem—a concept that falls within the field of community ecology. This is the study of how a given ecosystem functions—how space is structured, why certain species thrive in certain areas, and how individual species in the same community interact with one another and their habitat. This includes understanding how various species contribute to ecosystem services like pollination, water purification, and nutrient cycling.

132

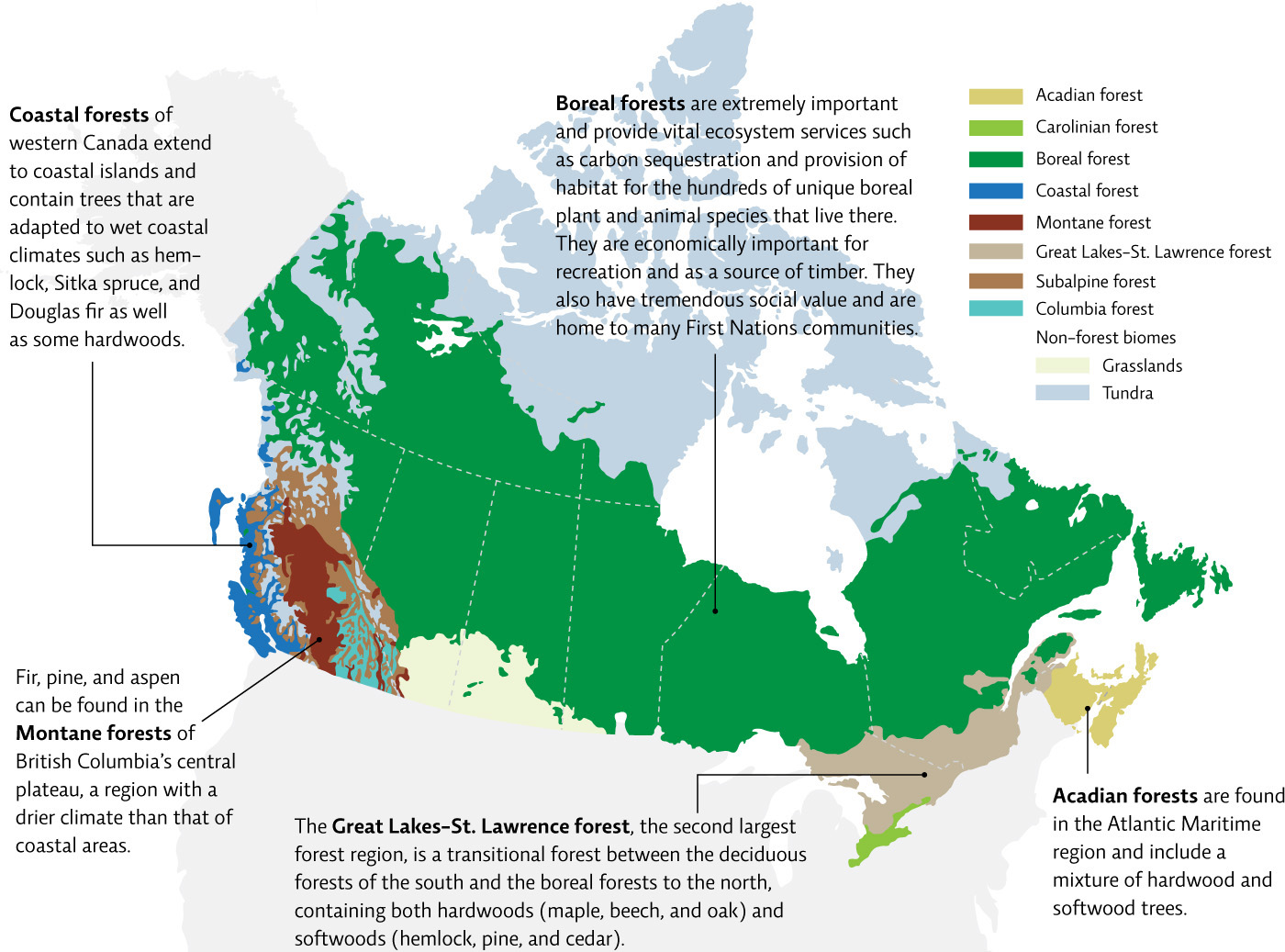

Many community ecologists are fascinated by the Acadian forest, because it contains a mix of tree species from both boreal and temperate zones, whose edges overlap to create a highly diverse mix of wildlife. The boreal forest—also known as taiga—is particularly important to Canada, as it covers more than half of the country. It is one of the world’s richest resources, serving as the breeding site for 30% of all North American birds, among them millions of ducks and waterfowl, and containing much of the world’s supply of liquid fresh water.

Although boreal forests are dominated by coniferous trees, approximately 30% of boreal land mass is covered by wetlands, mainly peatlands. Peatlands are distinct, moss-dominated ecological communities, which develop deep organic soils that store large amounts of carbon. Because mosses and other peatland plants decompose very slowly, these soils accumulate over thousands of years, making peat soils a relatively nonrenewable resource, and making damaged peatlands impossible to restore within human lifespans. Wetlands are not only highly biodiverse; they also provide extremely important water management services, including filtration and replenishment of groundwater reserves.

When the boreal forest transitions to the temperate forests found further south, you find a kaleidoscope of different organisms that rarely meet anywhere else in the world—aside from the mix of trees of many types, ages, and sizes, the Acadian forest contains a wide range of insects, worms, fungi, birds, rodents, and large predators such as hawks, bobcats, and black bears. The forest contains a wide range of habitats, from the dense tree cover Noseworthy hiked through to marshes and bogs (peatlands), which are the homes of fish, frogs, and the smaller aquatic organisms they feed on. Different levels of the forest itself, from forest floor to the upper canopy, offer different niches, occupied by different species. [infographic 8.1]

133

The Acadian forest is a prime example of how every piece of an ecosystem is interdependent—change one thing, and many others are affected. Ecologists often say “you can’t do one thing”; the loss of even one species can disrupt an entire ecosystem. For instance, cutting down trees reduces habitat for lichens, which drape from those trees; without these hanging lichens, there are fewer Northern Parula warblers (a small migratory songbird), which use those lichens for their nests. Fewer of these nests mean fewer warblers to feast on forest insects, and so more insects survive. It also means less food for predators that live off the eggs and small birds. Lichens, one of the few foods available in the winter, also help sustain deer and other year-round residents.

In the Acadian forests (and many areas worldwide) lichens are considered an indicator species—those that are particularly vulnerable to perturbations of the ecosystem. Most lichens are very vulnerable to the effects of air pollution, acting like sponges that soak up chemical pollutants in rainwater. If lichens start to disappear, this lets us know there is a problem and gives us time to act before other species are affected.

An ecosystem as diverse as the Acadian forest has several indicator species. Take the brown creeper, a tiny (7–8 grams), lanky songbird with a fairly narrow niche—it feeds on invertebrates found in the crevices formed by the deep bark furrows of large, live trees. “As soon as the density of those trees goes down, so does the density of the brown creeper,” says Marc-André Villard, a biologist at the Université de Moncton in New Brunswick.

Another indicator species of the Acadian forest is the ovenbird. With its striped belly and loud, characteristic call, it spends most of its time on the forest floor, where it feeds on invertebrates found in dead leaves. When trees are cut down and dragged through the soil, this reduces and disturbs the amount of leaf litter—essentially depriving the ovenbird of its main food source. “This small bird is sensitive to even small changes in tree density,” says Villard. “And when their numbers drop, it can take them years to recover.”