9.2 Biodiversity benefits humans and other species.

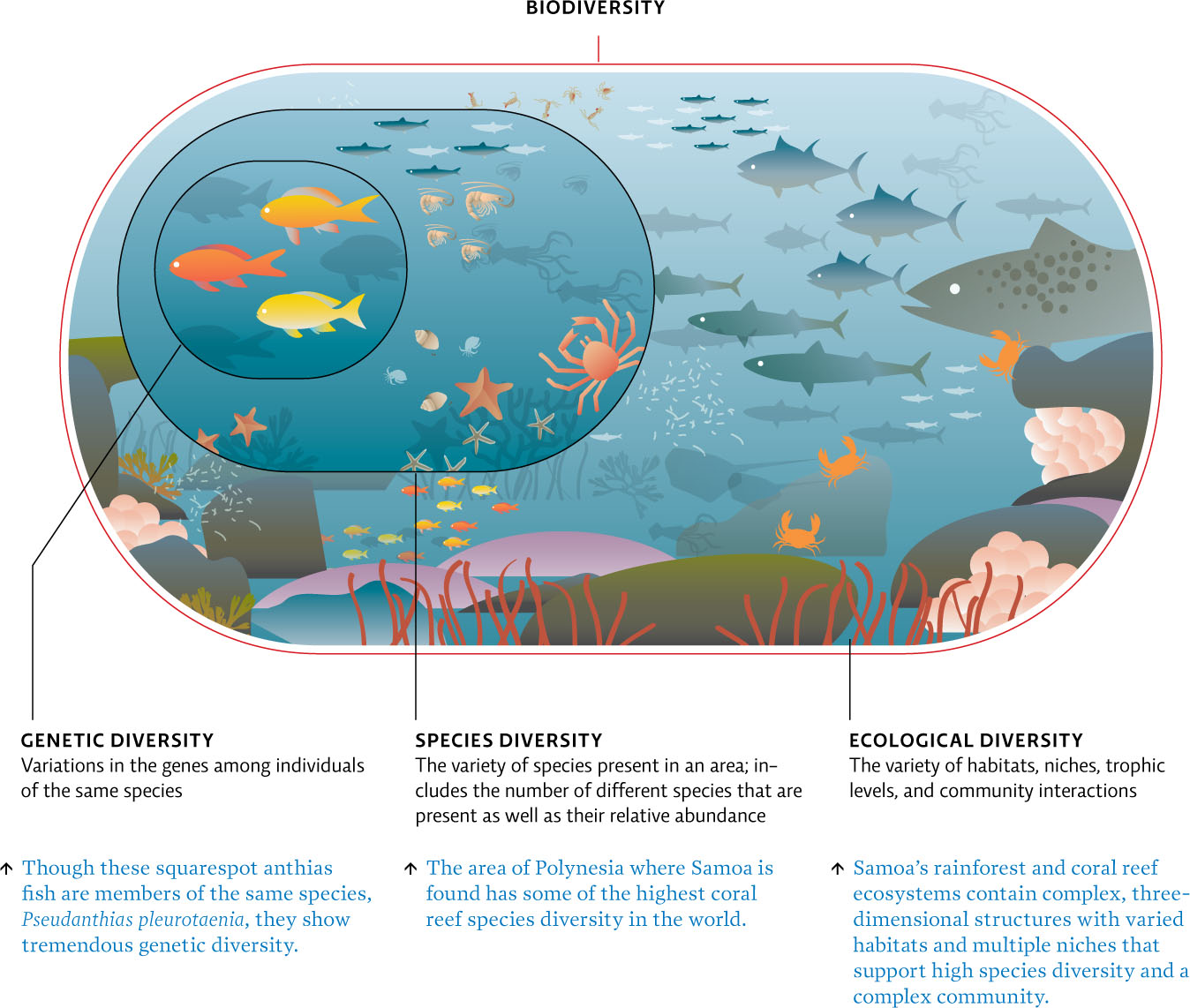

Why did Cox suspect that Samoa might hold the key to a cancer cure? Tropical regions like Samoa—warm, lush, close to the equator—contain the greatest concentration and variety of plant and animal life forms on Earth. This variety is called biodiversity. Countries of this region have both high species diversity and high genetic diversity. They also usually have high ecological diversity, a wide variety of communities and ecosystems with different habitats, many trophic levels, and lots of niches. [infographic 9.1]

152

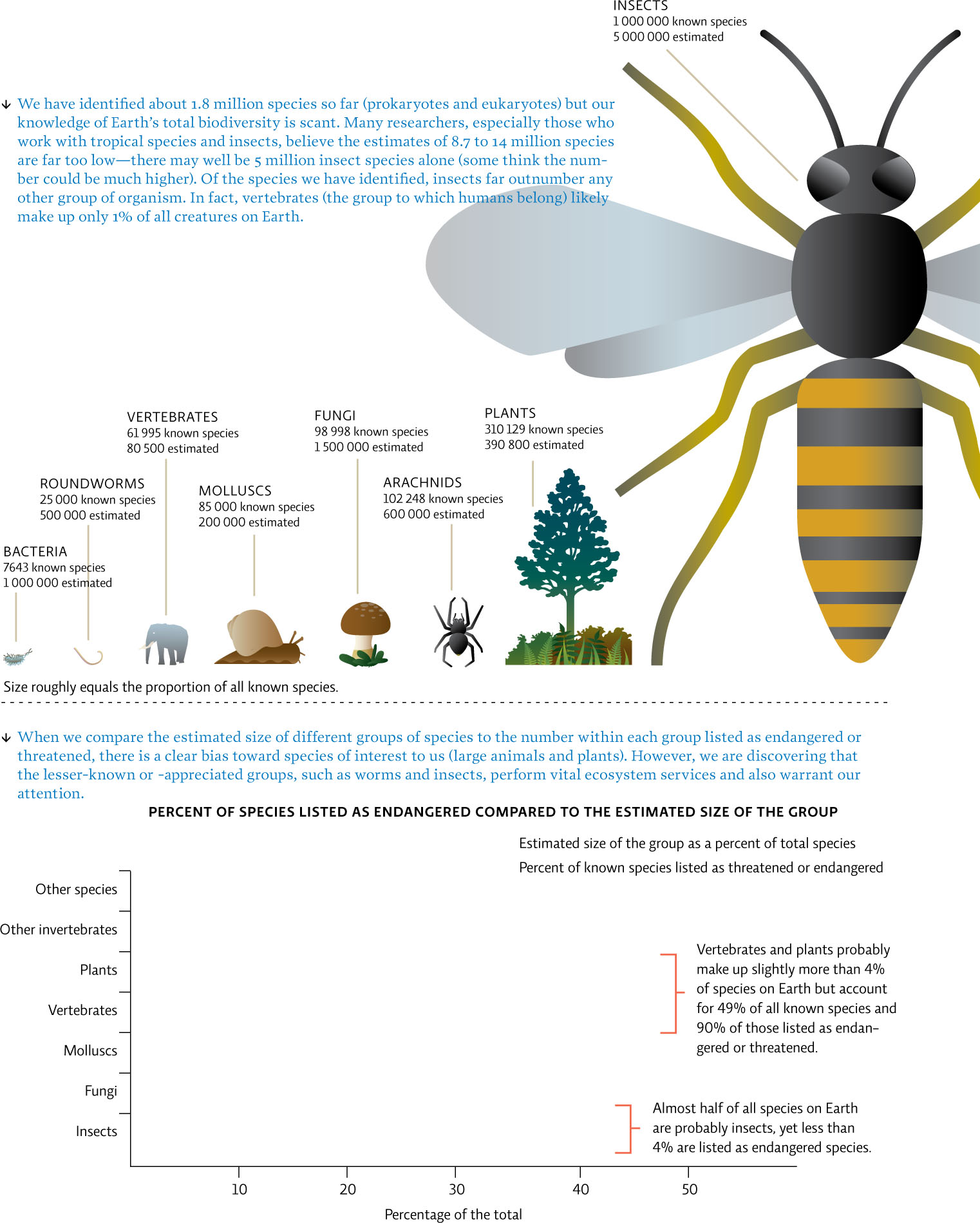

It is virtually impossible to know just how many species exist on Earth. This uncertainty has given rise to a awide range of estimates—anywhere from 3 to 100 million. Further, in a 2011 paper, researchers estimated that of all the species now living on Earth, we humans have yet to discover or identify about 86% of them. [infographic 9.2]

Such nearly unfathomable biodiversity brings with it many benefits. Samoa, like most other places around the world, depends on biodiversity to provide a vast array of ecosystem services: photosynthetic organisms (plants on land; algae and phytoplankton in the sea) bring in energy, produce oxygen, and sequester carbon. Other organisms capture and pass along important nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. Others still help purify the air and water and eventually become food for other creatures. And populations are kept in check by predators and competitors so that no single species grows too populous or gobbles up too many needed resources. For example, in the forests of Samoa, the tooth-billed pigeon is important for the propagation of mahogany, a species of tree found throughout Polynesia. The pigeon may be the only native animal that can open the trees seeds so new seedlings can take root. Meanwhile, adult mahogany trees provide habitat and food to a variety of insect, bird, mammal, and reptile species. They are also key players in carbon cycling and soil stabilization, and serve as a windbreak in coastal areas. (See Chapter 5 for more on ecosystem services.)

153

154

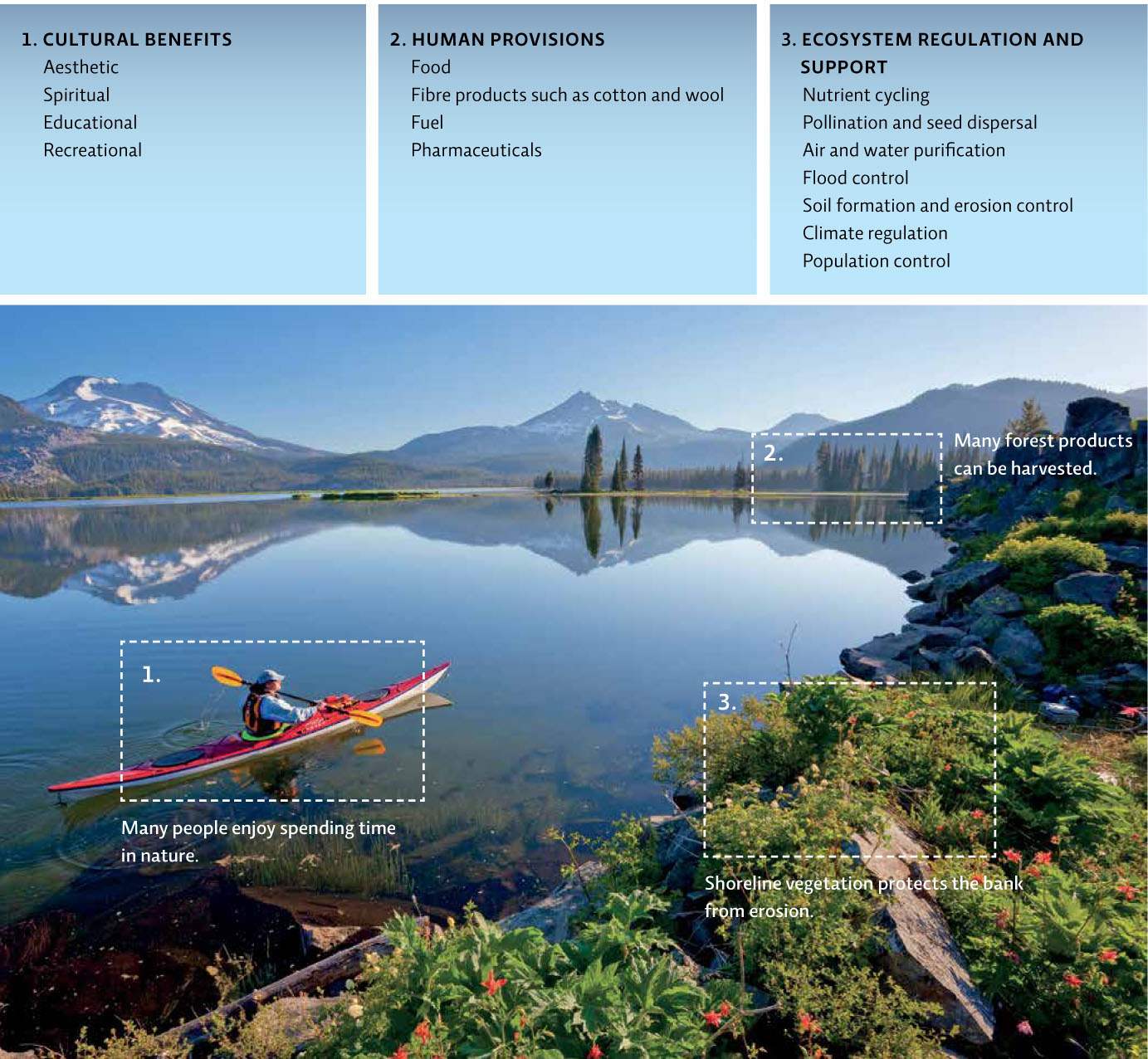

Biodiversity supplies cultural benefits as well—whether it is the enjoyment of a natural area for recreation or aesthetic appreciation, or a societal tradition rooted in nature. In Samoa, native foods are an important part of traditional feasts; the Sunday meal typically features tropical foods like fresh fruit, root vegetables including taro, and lots of seafood. Kava, a traditional drink prepared from the roots of a native pepper plant, is often drunk before ceremonial events and has a mild tranquilizing effect. It is also purported to have analgesic effects.

Biodiverse ecosystems have economic value, too. In Samoa, the forests provide not only food, fuel, and building material, but also pharmaceuticals. People use the chemicals they extract from plants not only to attend to their individual human health issues, but also as a source of income. [infographic 9.3]

The growing appreciation for the value of ecosystem services provided by species highlights the importance of species as members of an ecological community. But many people feel that the value of any given species goes beyond its instrumental value (i.e., the ecological, medicinal, or monetary benefits it can provide for humans) and contend that all species have intrinsic value and are therefore worth preserving.

Once they arrived in Samoa, Cox and his family settled in a thatched hut on the far western edge of the island in the village of Falealupo—just a few steps from the sea and as far as they could get from the comparatively modern neighbouring island of American Samoa. There, amid a tropical swirl of insects, humidity, and white sand, with no electricity or running water, Cox apprenticed himself to a mostly female cadre of healers. His primary teacher was Pela Lilo, an 82-year-old woman whose particular collection of plant-based remedies had been passed down to her through generations.

Lilo and her fellow healers shared hundreds of natural remedies with Cox—the bark of vavae (Ceiba pentandra) to treat asthma, leaves of the kuava tree (Psidium guajaba) for diarrhea, and root of ‘Ago (Curcuma longa) for rashes. It turned out that the Samoans did not have a word for breast cancer (one purported treatment for “lumpy breasts” did not prove effective against breast tumours). But they did have a treatment for “yellowing fever,” a disease Westerners know as Hepatitis C; boiling the bark of the mamala tree (Homalanthus nutans) and drinking the extract twice a day was known to relieve symptoms. After seeing a demonstration of the potion’s power, Cox gathered samples of mamala bark and sent them off (along with dozens of other promising roots, stems, and leaves) to colleagues at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), in Bethesda, Maryland, for testing.

155

But what he saw as a garden of medical promise, others saw as timber. And just as the mamala bark was yielding up its secrets to scientists at the NCI, loggers were negotiating with Falealupo’s villagers to clear-cut, or remove, all of the trees from the forests where this tree grew most abundantly. In Samoa, habitat destruction such as this had already gobbled up nearly 80% of the island’s lowland forests. Cox despaired at the thought of how many undiscovered medicines would be annihilated if the loggers had their way.

156