9.4 There are many different ways to protect and enhance biodiversity.

Cox has deployed a small team of ethnobotanists throughout the Pacific to take a census of island plants and to collect seeds from those species with fewer than 100 remaining specimens. This careful accounting—which often requires scaling down cliffs and dangling from helicopters—will provide the basis of a large-scale conservation effort that scientists hope to replicate in other regions of the world. “If we know what we are losing and where we’re losing it, we can plan a counter-offensive,” says David Burney, from the National Tropical Botanical Garden on the Hawaiian island of Kaua’i. “The census helps us to figure out what’s due to habitat loss, and so on.”

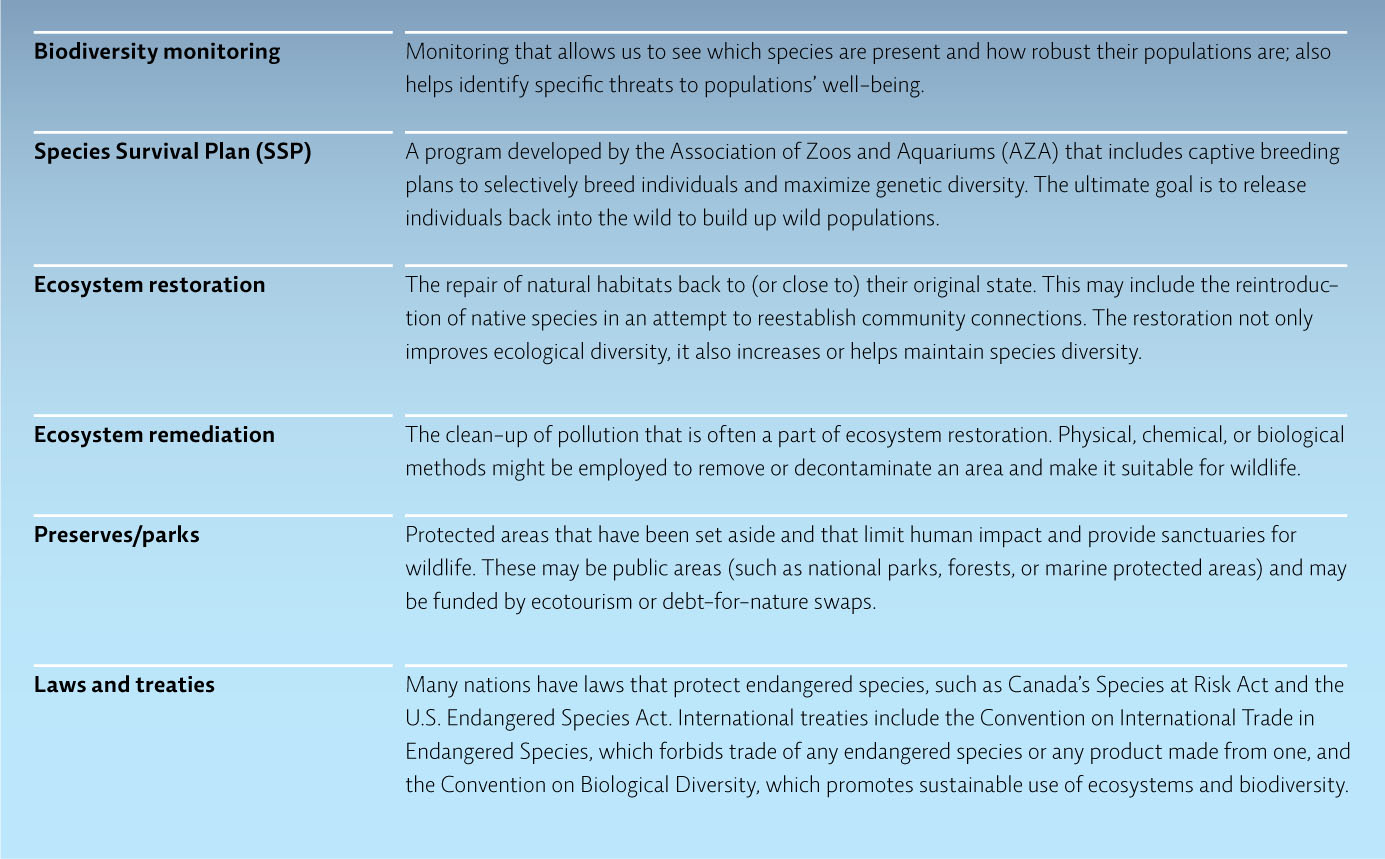

This type of basic field research—evaluating an area to see what species are present, how healthy and genetically diverse that species’ population is, and what threats the species face—is essential to protecting and maintaining biodiversity. After all, we can’t save or protect what we don’t even know exists or don’t realize is in danger of extinction. But it is only the first step.

Early programs that addressed species endangerment often took the single species approach: they singled out well-known animals, like pandas and condors, and focused on the specific threats those individual species faced, often using captive breeding programs to increase population sizes.

In some ways, this approach has been a huge success: it has saved grey wolves, eagles, and even brown pelicans from complete decimation. And it’s brought a great deal of attention and funding to conservation efforts. Indeed, the single species approach is still employed today. Zoos around the world participate in Species Survival Plans which use careful breeding programs to maximize genetic diversity. Among other things, this includes moving reproductive animals from zoo to zoo to introduce new genes into a breeding program or to minimize inbreeding. The ultimate goal of these programs is to release animals back into the wild.

But the tendency to focus on only those species (cute, furry, large) that are photogenic enough to capture the public’s attention means that many, if not most, species in need of help fall through the cracks (people are more likely to donate money to “Save the panda!” than to “Save the white warty-back pearly mussel!”). For that reason, many experts now support an ecosystem approach. This means identifying entire ecosystems—often biodiversity hotspots—that are at risk, and taking steps to restore or rehabilitate damaged habitat and then to protect it from further damage or exploitation. It may involve reforestation projects, removal of non-native species, restoration of a natural river’s flow patterns, or the clean-up of pollution (remediation)—the restoration goal depends on the ecosystem in question. Proponents of the ecosystem approach point out that by focusing on the ecosystem as a whole, the entire community benefits—not only the species we knew were endangered, but also those that we didn’t even know were there.

In order to shift to an ecosystem focus we must know how to identify when an ecosystem is in danger. Ecologists are developing metrics (factors that are measured) to assess ecosystem quality, such as species richness and evenness, soil health, water quality, plant community composition, and the abundance of non-native species.

The protection of habitat often includes establishing preserves—which can include national parks, forests, grasslands, and in the ocean, marine protected areas—where human access is deliberately restricted. In Samoa, 5% of the land is legally protected to one degree or another; the goal of Cox and his colleagues is to increase that to 15%. In other parts of the world, the preservation of natural areas can be funded by debt-for-nature swaps in which a wealthy nation forgives part of the debt of a developing nation in return for the developing nation’s pledge to protect certain ecosystems. So far, almost $1 billion in debt has been forgiven in these programs.

161

162

Laws and international treaties also offer species more formal protection, often by mandating the steps outlined above (namely monitoring, restoration, and protection). The Species at Risk Act (SARA), passed in 2002, provides provisions for officially identifying a species as endangered (a listed species) and mandates that listed species and their habitats be protected in Canada. In many cases, this law has been very successful, but its effectiveness is perpetually hampered by inadequate funding and by conflicts with economic interests and a slow, political approval process. International treaties such as the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species and the Convention on Biological Diversity offer protection of endangered and threatened species beyond the borders of an individual country. [infographic 9.7]