Matched pairs and block designs

Completely randomized designs are the simplest statistical designs for experiments. They illustrate clearly the principles of control and randomization. However, completely randomized designs are often inferior to more elaborate statistical designs. In particular, matching the subjects in various ways can produce more precise results than simple randomization.

One common design that combines matching with randomization is the matched pairs design. A matched pairs design compares just two treatments. Choose pairs of subjects that are as closely matched as possible. Assign one of the treatments to each subject in a pair by tossing a coin or reading odd and even digits from Table A. Sometimes, each “pair” in a matched pairs design consists of just one subject, who gets both treatments together (for example, each on a different arm or leg) or one after the other. Each subject serves as his or her own control. The order of the treatments can influence the subject’s response, so we randomize the order for each subject, again by a coin toss.

127

EXAMPLE 9 Testing insect repellants

Consumer Reports describes a method for comparing the effectiveness of two insect repellants. The active ingredient in one is 15% Deet. The active ingredient in the other is oil of lemon eucalyptus. Repellants are tested on several volunteers. For each volunteer, the left arm is sprayed with one of the repellants and the right arm with the other. This is a matched pairs design in which each subject compares two insect repellants. To guard against the possibility that responses may depend on which arm is sprayed, which arm receives which repellant is determined randomly. Beginning 30 minutes after applying the repellants, once every hour, volunteers put each arm in separate 8-cubic-foot cages containing 200 disease-free female mosquitoes in need of a blood meal to lay their eggs. Volunteers leave their arms in the cages for five minutes. The repellant is considered to have failed if a volunteer is bitten two or more times in a five-minute session. The response is the number of one-hour sessions until a repellant fails.

Matched pairs designs use the principles of comparison of treatments and randomization. However, the randomization is not complete—we do not randomly assign all the subjects at once to the two treatments. Instead, we randomize only within each matched pair. This allows matching to reduce the effect of variation among the subjects. Matched pairs are an example of block designs.

Block design

A block is a group of experimental subjects that are known before the experiment to be similar in some way that is expected to affect the response to the treatments. In a block design, the random assignment of subjects to treatments is carried out separately within each block.

A block design combines the idea of creating equivalent treatment groups by matching with the principle of forming treatment groups at random. Blocks are another form of control. They control the effects of some outside variables by bringing those variables into the experiment to form the blocks. Here are some typical examples of block designs.

128

![]() Hawthorne effect The Hawthorne effect is a term referring to the tendency of some people to work harder and perform better when they are participants in an experiment. Individuals may change their behavior due to the attention they are receiving from researchers rather than because of any manipulation of independent variables.

Hawthorne effect The Hawthorne effect is a term referring to the tendency of some people to work harder and perform better when they are participants in an experiment. Individuals may change their behavior due to the attention they are receiving from researchers rather than because of any manipulation of independent variables.

The effect was first described in the 1950s by researcher Henry A. Landsberger during his analysis of experiments conducted during the 1920s and 1930s at the Hawthorne works electric company.

The electric company had commissioned research to determine if there was a relationship between productivity and work environment.

The focus of the original studies was to determine if increasing or decreasing the amount of light workers received would have an effect on worker productivity. Employee productivity seemed to increase due to the changes but then decreased after the experiment was over. Researchers suggested that productivity increased due to attention from the research team and not because of changes to the experimental variables. Lansdberger defined the Hawthorne effect as a short-term improvement in performance caused by observing workers.

Later research into the Hawthorne effect has suggested that the original results may have been overstated. In 2009, researchers at the University of Chicago reanalyzed the original data and found that other factors also played a role in productivity and that the effect originally described was weak at best.

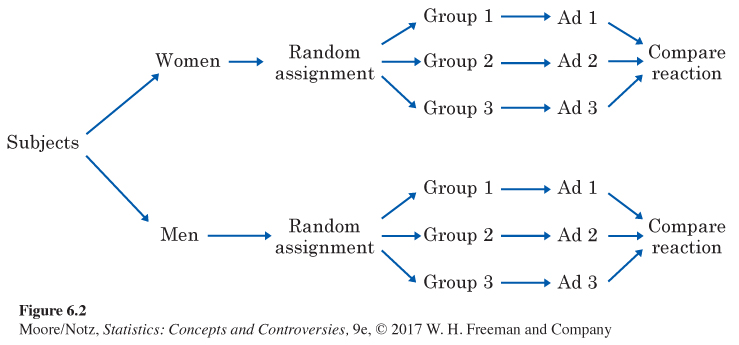

EXAMPLE 10 Men, women, and advertising

Women and men respond differently to advertising. An experiment to compare the effectiveness of three television commercials for the same product will want to look separately at the reactions of men and women, as well as assess the overall response to the ads.

A completely randomized design considers all subjects, both men and women, as a single pool. The randomization assigns subjects to three treatment groups without regard to their sex. This ignores the differences between men and women. A better design considers women and men separately. Randomly assign the women to three groups, one to view each commercial. Then separately assign the men at random to three groups. Figure 6.2 outlines this improved design.

129

EXAMPLE 11 Comparing welfare systems

A social policy experiment will assess the effect on family income of several proposed new welfare systems and compare them with the present welfare system. Because the future income of a family is strongly related to its present income, the families who agree to participate are divided into blocks of similar income levels. The families in each block are then allocated at random among the welfare systems.

A block is a group of subjects formed before an experiment starts. We reserve the word “treatment” for a condition that we impose on the subjects. We don’t speak of six treatments in Example 10 even though we can compare the responses of six groups of subjects formed by the two blocks (men, women) and the three commercials. Block designs are similar to stratified samples, which we discussed in Chapter 4. Blocks and strata both group similar individuals together. We use two different names only because the idea developed separately for sampling and experiments. The advantages of block designs are the same as the advantages of stratified samples. Blocks allow us to draw separate conclusions about each block—for example, about men and women in the advertising study in Example 10. Blocking also allows more precise overall conclusions because the systematic differences between men and women can be removed when we study the overall effects of the three commercials. The idea of blocking is an important additional principle of statistical design of experiments. A wise experimenter will form blocks based on the most important unavoidable sources of variability among the experimental subjects. Randomization will then average out the effects of the remaining variation and allow an unbiased comparison of the treatments.

NOW IT’S YOUR TURN

Question 6.2

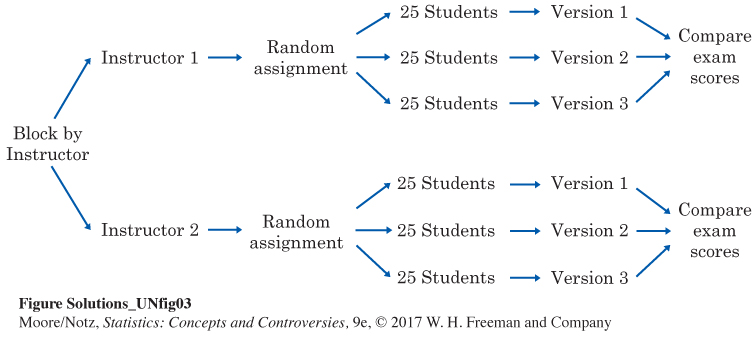

6.2 Multiple-choice exams. A researcher was interested in whether the order of the answers to multiple-choice questions affects exam scores. He made three versions of an exam. Each version had the same questions and the same set of answers, but the order of the possible answers was different for each version. The three versions were given to students in two classes having different instructors. Each class had an enrollment of 75 students. The researcher was concerned that scores might also depend on instructor, so instructor was treated as a blocking variable. Use a diagram to outline a block design for this experiment. Use Figure 6.2 as a model.

6.2 In this experiment, the instructors are the blocks, for which the 75 students in each class are split randomly into three groups of 25, each receiving a different version of the test. Exam scores would then be compared as the response variable. Here is a sample diagram.

Like the design of samples, the design of complex experiments is a job for experts. Now that we have seen a bit of what is involved, for the remainder of the text we will usually assume that most experiments were completely randomized.

130

STATISTICAL CONTROVERSIES

Is It or Isn’t It a Placebo?

Natural supplements are big business: creatine and amino acid supplements to enhance athletic performance; green tea extract to boost the immune system; yohimbe bark to help your sex life; grapefruit extract and apple cider vinegar to support weight loss; white kidney bean extract to block carbs. Store shelves and websites are filled with exotic substances claiming to improve your health.

A therapy that has not been compared with a placebo in a randomized experiment may itself be just a placebo. In the United States, the law requires that new prescription drugs and new medical devices show their safety and effectiveness in randomized trials.

What about those “natural remedies”? The law allows makers of herbs, vitamins, and dietary supplements to claim without any evidence that they are safe and will help “natural conditions.” They can’t claim to treat “diseases.” Of course, the boundary between natural conditions and diseases is vague. Without any evidence whatsoever, we can claim that Dr. Moore’s Old Indiana Extract promotes healthy hearts. But without clinical trials and an okay by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), we can’t claim that it reduces the risk of heart disease. No doubt lots of folks will think that “promotes healthy hearts” means the same thing as “reduces the risk of heart disease” when they see our advertisements. We also don’t have to worry about what dose of Old Indiana Extract our pills contain or about what dose might actually be toxic.

Should the FDA require natural remedies to meet the same standards as prescription drugs? What does your statistical training tell you about claims not backed up by well-designed experiments? What about the fact that sometimes these natural remedies have real effects? Should that be sufficient for requiring FDA approval on natural remedies?