11.1 Prenatality: A Womb with a View

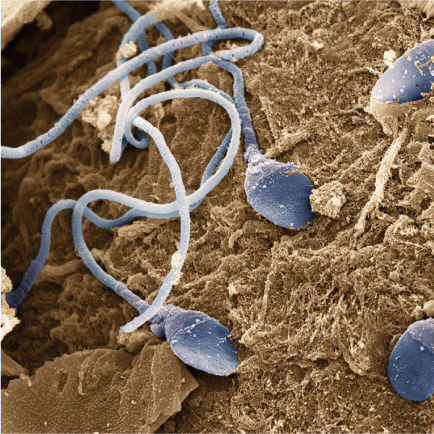

You probably calculate your age by counting your birthdays. But the fact is that on the day you were born, you were already 9 months old. The prenatal stage of development ends with birth and begins 9 months earlier when about 200 million sperm make the journey from a woman’s vagina, through her uterus, and on to her fallopian tubes. That journey is a perilous one. Many of the sperm have defects that prevent them from swimming vigorously enough to make any progress, and others get stuck in the spermatazoidal equivalent of a traffic jam in which too many sperm are headed in the same direction at the same time. Of those that do manage to make their way through the uterus, many will take a wrong turn and end up in the fallopian tube that does not contain an egg. In fact, a mere 200 or so of the original 200 million sperm will manage to find the correct fallopian tube and get close enough to an egg to release digestive enzymes that erode the egg’s protective outer layer. The moment the first sperm manages to penetrate the egg’s coating, the egg will release a chemical that seals the coating and keeps all the other sperm from entering. After triumphing over 199,999,999 of its closest friends, this single successful sperm will shed its tail and fertilize the egg. About 12 hours later, the egg will merge with the nuclei of the sperm, and the prenatal development of a unique human being will begin.

427

Prenatal Development

What are the three prenatal stages?

A zygote is a fertilized egg that contains chromosomes from both an egg and a sperm. From the first moment of its existence, a zygote has one thing in common with the person it will someday become: sex. Each human sperm and each human egg contain 23 chromosomes. One of these chromosomes (the 23rd) comes in two varieties known as X and Y. An egg always has an X chromosome, but a sperm can have either an X or a Y chromosome. If the egg is fertilized by a sperm that has a Y chromosome, then the zygote is male (XY), and if it is fertilized by a sperm that has an X chromosome, then the zygote is female (XX).

The germinal stage is the 2-

If the zygote successfully implants itself in the uterine wall, it earns the right to be called an embryo and a new stage of development begins. The embryonic stage is a period that lasts from the 2nd week until about the 8th week (see FIGURE 11.1). During this stage, the embryo continues to divide and its cells begin to differentiate. Merely 1 inch long, the embryo already has a beating heart and other body parts, such as arms and legs. Embryos that have XY chromosomes begin to produce a hormone called testosterone, which masculinizes their reproductive organs.

BIOPHOTO ASSOCIATES/SCIENCE SOURCE

JAMES STEVENSON/SCIENCE SOURCE

428

At about 9 weeks, the embryo gets a new name: fetus. The fetal stage is a period that lasts from the 9th week until birth. The fetus has a skeleton and muscles that make it capable of movement. It develops a layer of insulating fat beneath its skin, and its digestive and respiratory systems mature. The cells that will ultimately become the brain divide very quickly around the 3rd and 4th week after conception, and this process is more or less complete by 24 weeks. During the fetal stage, brain cells begin to generate axons and dendrites (which permit communication with other brain cells). They also begin to undergo a process (described in the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter) known as myelination, which is the formation of a fatty sheath around the axons of a neuron. Just as plastic sheathing insulates a wire, myelin insulates a brain cell and prevents the leakage of neural signals that travel along the axon. This process starts during the fetal stage but doesn’t end for years; the myelination of the cortex, for example, continues into adulthood.

Why are human beings born with underdeveloped brains?

Although the brain undergoes rapid and complex growth during the fetal period, at birth it is nowhere near its adult size. Whereas a newborn chimpanzee’s brain is nearly 60% of its adult size, a newborn human’s brain is only 25% of its adult size, which is to say that 75% of a human’s brain development occurs outside the womb. Why are humans born with such underdeveloped brains?

First, adult humans have huge heads. If a newborn human’s head were 60% of its adult size—

Prenatal Environment

How does the uterine environment affect the unborn child?

The womb is an environment that has a powerful impact on development (Coe & Lubach, 2008; Glynn & Sandman, 2011; Wadhwa, Sandman, & Garite, 2001). For example, the placenta is the organ that physically links the bloodstreams of the mother and the embryo or fetus and permits the exchange of certain chemicals. That’s why the foods a woman eats during pregnancy can affect her unborn child. The children of mothers who receive insufficient nutrition during pregnancy often have physical problems (Stein et al., 1975) and psychological problems, most notably an increased risk of schizophrenia and antisocial personality disorder (Neugebauer, Hoek, & Susser, 1999; Susser, Brown, & Matte, 1999). The foods a woman eats during pregnancy can also shape her child’s food preferences: Studies show that infants tend to like the foods and spices that their mothers ate while they were in utero (Mennella, Johnson, & Beauchamp, 1995).

But it isn’t just food that affects the fetus. Almost anything a woman eats, drinks, inhales, injects, sniffs, snorts, or rubs on her skin can pass through the placenta. Agents that impair development are called teratogens, which literally means “monster makers.” Teratogens include environmental poisons such as lead in the water, paint dust in the air, or mercury in fish, but the most common teratogens can be purchased at 7-

429

OTHER VOICES: Men, Who Needs Them?

All of the authors of this book are men, so we’re very much in favor of their continued existence. But in this only-

…With expanding reproductive choices, we can expect to see more women choose to reproduce without men entirely. Fortunately, the data for children raised by only females is encouraging. As the Princeton sociologist Sara S. McLanahan has shown, poverty is what hurts children, not the number or gender of parents.

That’s good, since women are both necessary and sufficient for reproduction, and men are neither. From the production of the first cell (egg) to the development of the fetus and the birth and breast-

Think about your own history. Your life as an egg actually started in your mother’s developing ovary, before she was born; you were wrapped in your mother’s fetal body as it developed within your grandmother.

After the two of you left Grandma’s womb, you enjoyed the protection of your mother’s prepubescent ovary. Then, sometime between 12 and 50 years after the two of you left your grandmother, you burst forth and were sucked by her fimbriae into the fallopian tube. You glided along the oviduct, surviving happily on the stored nutrients and genetic messages that Mom packed for you.

Then, at some point, your father spent a few minutes close by, but then left. A little while later, you encountered some very odd tiny cells that he had shed. They did not merge with you, or give you any cell membranes or nutrients—

Over the next nine months, you stole minerals from your mother’s bones and oxygen from her blood, and you received all your nutrition, energy and immune protection from her. By the time you were born your mother had contributed six to eight pounds of your weight. Then as a parting gift, she swathed you in billions of bacteria from her birth canal and groin that continue to protect your skin, digestive system and general health. In contrast, your father’s 3.3 picograms of DNA comes out to less than one pound of male contribution since the beginning of Homo sapiens 107 billion babies ago.

And while birth seems like a separation, for us mammals it’s just a new form of attachment to our female parent. If your mother breast-

I don’t dismiss the years I put in as a doting father, or my year at home as a house husband with two young kids. And I credit my own father as the more influential parent in my life. Fathers are of great benefit. But that is a far cry from “necessary and sufficient” for reproduction.

If a woman wants to have a baby without a man, she just needs to secure sperm (fresh or frozen) from a donor (living or dead). The only technology the self-

Ultimately the question is, does “mankind” really need men? With human cloning technology just around the corner and enough frozen sperm in the world to already populate many generations, perhaps we should perform a cost–benefit analysis.

It’s true that men have traditionally been the breadwinners. But women have been a majority of college graduates since the 1980s, and their numbers are growing. It’s also true that men have, on average, a bit more muscle mass than women. But in the age of ubiquitous weapons, the one with the better firepower (and knowledge of the law) triumphs.

Meanwhile women live longer, are healthier and are far less likely to commit a violent offense. If men were cars, who would buy the model that doesn’t last as long, is given to lethal incidents and ends up impounded more often?

Recently, the geneticist J. Craig Venter showed that the entire genetic material of an organism can be synthesized by a machine and then put into what he called an “artificial cell.” This was actually a bit of press-

When I explained this to a female colleague and asked her if she thought that there was yet anything irreplaceable about men, she answered, “They’re entertaining.”

Gentlemen, let’s hope that’s enough.

From the New York Times, August 24, 2012. © 2012 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

430

Tobacco is the other common teratogen, and there is no debate about its effects. About 20% of American mothers admit to smoking during pregnancy (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005). The half-

What can a fetus hear?

The prenatal environment is rich with chemicals, and it is also rich with information. Unlike an automobile, which operates only after it has been fully assembled, the human brain is operating while it is being built, and research shows that the developing fetus can sense stimulation and learn from it. Wombs are dark because only the brightest light can filter through the mother’s abdomen, but they are not quiet. The fetus can hear its mother’s heartbeat, the gastrointestinal sounds associated with her digestion, and her voice. How do we know? Newborns will suck a nipple more vigorously when they hear the sound of their mother’s voice than when they hear the voice of a female stranger (Querleu et al., 1984), demonstrating that they are more familiar with the former. Similarly, newborns whose mothers read aloud from The Cat in the Hat during their pregnancies react as though the story is familiar (DeCasper & Spence, 1986). Newborns who are presented with words from two languages prefer hearing their mother’s native language—

Developmental psychology studies continuity and change across the life span.

Developmental psychology studies continuity and change across the life span. The prenatal stage of development begins when a sperm fertilizes an egg, producing a zygote. The zygote, which contains chromosomes from both the egg and the sperm, develops into an embryo at 2 weeks and then into a fetus at 8 weeks.

The prenatal stage of development begins when a sperm fertilizes an egg, producing a zygote. The zygote, which contains chromosomes from both the egg and the sperm, develops into an embryo at 2 weeks and then into a fetus at 8 weeks. The fetal environment has important physical and psychological influences on the fetus. In addition to the food a pregnant woman eats, teratogens, or agents that impair fetal development, can affect the fetus. Some of the most common teratogens are tobacco and alcohol.

The fetal environment has important physical and psychological influences on the fetus. In addition to the food a pregnant woman eats, teratogens, or agents that impair fetal development, can affect the fetus. Some of the most common teratogens are tobacco and alcohol. Although the fetus cannot see much in the womb, it can hear sounds and become familiar with those it hears often, such as its mother’s voice.

Although the fetus cannot see much in the womb, it can hear sounds and become familiar with those it hears often, such as its mother’s voice.

431