5.4 Hypnosis: Open to Suggestion

You may have never been hypnotized, but you have probably heard or read about it. Its wonders are often described with an air of amazement, and demonstrations of stage hypnosis make it seem very powerful and mysterious. When you think of hypnosis, you may envision people completely under the power of a hypnotist, who is ordering them to dance like a chicken or perhaps “regress” to early childhood and talk in childlike voices. Many common beliefs about hypnosis are false. Hypnosis refers to a social interaction in which one person (the hypnotist) makes suggestions that lead to a change in another person’s (the subject’s) subjective experience of the world (Kirsch et al., 2011). The essence of hypnosis is in leading people to expect that certain things will happen to them that are outside their conscious will (Wegner, 2002).

5.4.1 Induction and Susceptibility

To induce hypnosis, a hypnotist may ask the person to be hypnotized to sit quietly and focus on some item, such as a spot on the wall (or a swinging pocket watch), and then make suggestions to the person about what effects hypnosis will have (e.g., “your eyelids are slowly closing” or “your arms are getting heavy”). Even without hypnosis, some suggested behaviours might commonly happen just because a person is concentrating on them—

215

What makes someone easy to hypnotize?

Not everyone is equally hypnotizable. Susceptibility varies greatly. Some highly suggestible people are very easily hypnotized, most people are only moderately influenced, and some people are entirely unaffected by attempts at hypnosis. Susceptibility is not easily predicted by a person’s personality traits. A hypnotist will typically test someone’s hypnotic susceptibility with a series of suggestions designed to put a person into a more easily influenced state of mind. One of the best indicators of a person’s susceptibility is the person’s own judgment. So, if you think you might be hypnotizable, you may well be (Hilgard, 1965). People with active, vivid imaginations, or who are easily absorbed in activities such as watching a movie, are also somewhat more prone to be good candidates for hypnosis (Sheehan, 1979; Tellegen & Atkinson, 1974).

5.4.2 Hypnotic Effects

From watching stage hypnotism, you might think that the major effect of hypnosis is making people do peculiar things. So what do we actually know to be true about hypnosis? There are some impressive demonstrations that suggest real changes occur in those under hypnosis. At the 1849 festivities for Prince Albert of England’s birthday, for example, a hypnotized guest was asked to ignore any loud noises and then did not even flinch when a pistol was fired near his face. These days, hypnotists are discouraged from using firearms during stage shows, but they often have volunteers perform other impressive feats. One common claim for superhuman strength under hypnosis involves asking a hypnotized person to become “stiff as a board” and lie unsupported with shoulders on one chair and feet on another while the hypnotist stands on the hypnotized person’s body.

Studies have demonstrated that hypnosis can undermine memory, but with important limitations. People susceptible to hypnosis can be led to experience posthypnotic amnesia, the failure to retrieve memories following hypnotic suggestions to forget. Ernest Hilgard (1986) taught a hypnotized person the populations of some remote cities, for example, and then suggested that the participant forget the study session; the person was quite surprised after the session at being able to give the census figures correctly. Asked how he knew the answers, the individual decided he might have learned them from a TV program. Such amnesia can then be reversed in subsequent hypnosis.

Importantly, research has found that only memories that were lost under hypnosis can be retrieved through hypnosis. The false claim that hypnosis helps people to unearth memories that they are not able to retrieve in normal consciousness seems to have surfaced because hypnotized people often make up memories to satisfy the hypnotist’s suggestions. For example, Paul Ingram, a sheriff’s deputy accused of sexual abuse by his daughters in the 1980s, was asked by interrogators in session after session to relax and imagine having committed the crimes. He emerged from these sessions having confessed to dozens of horrendous acts of “satanic ritual abuse.” These confessions were called into question, however, when independent investigator Richard Ofshe used the same technique to ask Ingram about a crime that Ofshe had simply made up out of thin air, something of which Ingram had never been accused. Ingram produced a three-

216

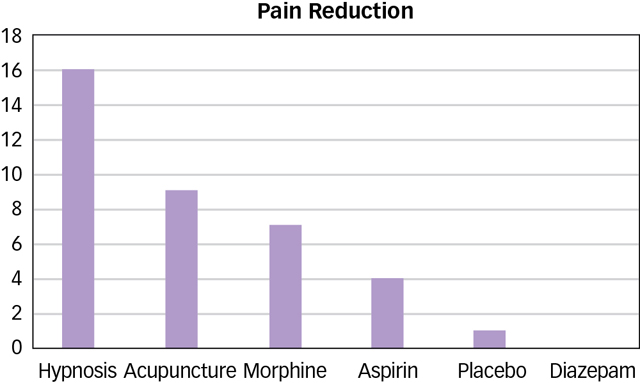

Hypnosis can lead to measurable physical and behavioural changes in the body. One well-

What evidence supports the idea that hypnosis leads to observable changes in the body?

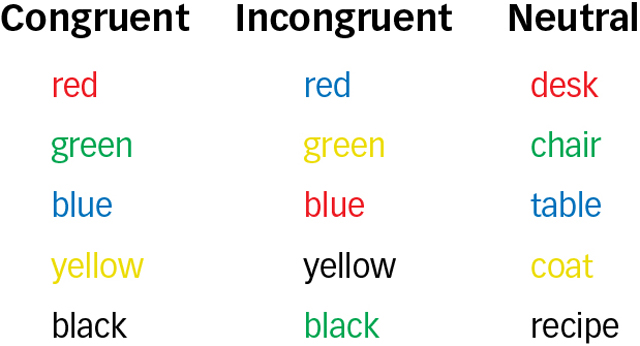

Hypnosis also has been shown to enable people to control mental processes previously believed to be beyond conscious control. For instance, the Stroop task (Stroop, 1935) is a classic psychological test in which a person is asked to name the colour of words on a page (appearing in ink that is red, blue, green, etc.). This is a simple task. However, sometimes the words themselves are the names of colours, but are printed in a different colour of the ink. It turns out that people are significantly slower, and make more errors, when naming ink colours that do not match the content of the word (e.g., when the word “blue” is written in red ink) than if the content is neutral or congruent (e.g., if the word “desk” or “red” is written in red ink) (see FIGURE 5.15). This effect is present no matter how hard we try. Amazingly, the effect is completely eliminated when highly suggestible people are hypnotized and told to respond to all words the same way (Raz et al., 2002). Importantly, though, follow-

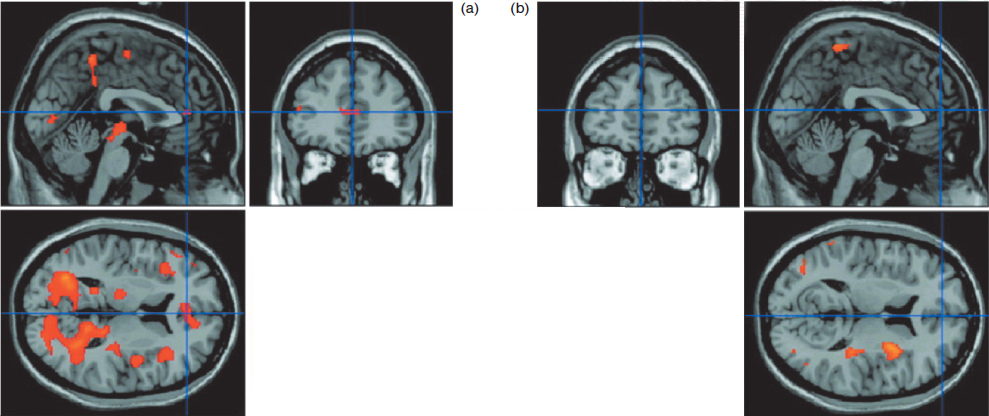

Nevertheless, people under hypnotic suggestion are not merely telling hypnotists what they want to hear. Instead, they seem to be experiencing what they have been asked to experience. Under hypnotic suggestion, for example, regions of the brain responsible for colour vision are activated in highly hypnotizable people when they are asked to perceive colour, even when they are really shown grey stimuli (Kosslyn et al., 2000). While engaged in the Stroop task, people who can eliminate the Stroop effect under suggestion show decreased activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), the part of the brain involved in conflict monitoring (FIGURE 5.16) (Raz, Fan, & Posner, 2005), consistent with the lack of conflict perceived between the colour name and ink. Overall, hypnotic suggestion appears to change the subjective perception of those experiencing it, as reflected by changes in their self-

Hypnosis is an altered state of consciousness characterized by suggestibility.

Although many claims for hypnosis overstate its effects, hypnosis can create the experience that one’s actions are occurring involuntarily, create analgesia, and even change brain activations in ways that suggest that hypnotic experiences are more than imagination

217

OTHER VOICES: The Blink of an Eye

On December, 8, 1995, Jean-

As incapacitated as he was, he was able to write a remarkable memoir, Le scaphandre et le papillon, which he “dictated” to an assistant one letter at a time by blinking his left eyelid. The letters of the alphabet, organized in order of frequency, were presented on a screen, his assistant would point to each in turn, and Bauby would blink once, yes, at the appropriate letter. In the long hours of solitude at night in his hospital bed, he would compose and memorize the sections of the memoir, to be dictated the next morning. His story was translated into English as The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.

In his book Bauby detailed the mundane experiences of every day life—

He was frustrated at no longer being able to communicate fluently (he was a witty and engaging conversationalist before the stroke). Jokes and witticisms that he would normally use fell flat when they were dictated labouriously, one letter at a time. The enforced humourlessness was one of the main limitations of his condition.

He related how one day he was playing hangman with his son (since he could guess letters one at a time). He was suddenly overcome by an intense grief because although his son was physically close, he could not ruffle his hair, hug him close, or even touch him. He called this situation “monstrous … horrible,” and startled his son when an involuntary sob escaped him.

Despite the sadness of his situation, he also noted the beauty of memory and imagination: how, like a butterfly, his thoughts could go where they please—

Bauby wrote about the reality of his situation—

Bauby died of heart failure in late winter of 1997, a few days after the publication of his extraordinary memoir.

Quotations from Bauby, J. (1997). The diving bell and the butterfly. London, UK: Fourth Estate.

218