10.5 Who Is Most Intelligent?

If everyone in the world were equally intelligent, we probably would not even have a word for it. What makes intelligence such an interesting and important topic is that some individuals—

10.5.1 Individual Differences in Intelligence

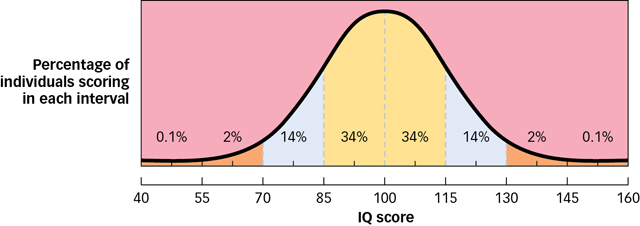

The average IQ is 100, and the vast majority of us—

Those of us who occupy the large middle of the intelligence spectrum often embrace a number of myths about those who live at the extremes. For example, movies typically portray the “tortured genius” as a person (usually a male person) who is brilliant, creative, misunderstood, despondent, and more than a little bit weird. Although some psychologists do think there is a link between creative genius and certain forms of psychopathology (Gale et al., 2012; Jamison, 1993; cf. Schlesinger, 2012), for the most part Hollywood has the relationship between intelligence and mental illness backwards: People with very high intelligence are less prone to mental illness than are people with very low intelligence (Dekker & Koot, 2003; Didden et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2002). Indeed, a 15 point decrease in IQ at age 20 is associated with a 50 percent increase in the risk of later hospitalization for schizophrenia, mood disorder, and alcohol-

Another staple of Hollywood’s vivid imagination is the “maladjusted child braniac.” In fact, research suggests that very high IQ children are about as well-

417

What one thing most clearly distinguishes gifted children?

It is worth noting that gifted children are rarely gifted in all departments, but instead have gifts in a single domain such as mathematics, language, or music. More than 95 percent of gifted children show a sharp disparity between their mathematical and verbal abilities (Achter, Lubinski, & Benbow, 1996). Because gifted children tend to be “single-

On the other end of the intelligence spectrum are people with intellectual disabilities, which can range from mild (50 < IQ < 69) to moderate (35 < IQ < 49) to severe (20 < IQ < 34) to profound (IQ < 20). About 70 percent of people with IQs in this range are male. Two of the most common causes of intellectual disability are Down syndrome (caused by the presence of a third copy of chromosome 21) and fetal alcohol syndrome (caused by a mother’s alcohol use during pregnancy). These intellectual disabilities are quite general, and people who have them typically show impaired performance on most or all cognitive tasks. Myths about people with intellectual disabilities abound. For example, many people think the intellectually disabled are mentally ill, but in fact, their rate of mental illness is similar to that found in the general population (Deb, Thomas, & Bright, 2001). Another myth about the intellectually disabled is that they are unhappy. A recent survey of people with Down syndrome (Skotko, Levine, & Goldstein, 2011) revealed that more than 96 percent are happy with their lives, like who they are, and like how they look. People with intellectual disabilities face many challenges, and being misunderstood is one of the most difficult.

10.5.2 Group Differences in Intelligence

In the early 1900s, Stanford professor Lewis Terman improved on Binet and Simon’s work and produced the intelligence test now known as the Stanford–

A century later, these sentences make most of us cringe. Terman appeared to be making three claims: First, that intelligence is influenced by genes; second, that members of some racial groups score better than others on intelligence tests; and third, that the difference in scores is due to a difference in genes. Virtually all modern scientists agree that Terman’s first two claims are true: Intelligence is influenced by genes and some groups do perform better than others on intelligence tests. However, Terman’s third claim—

418

Before answering that question we should be clear about one thing: Between-

But fair or not, they do. Asians routinely outscore Caucasians, who routinely outscore Latinos, who routinely outscore blacks (Neisser et al., 1996; Rushton, 1995). Women routinely outscore men on tests that require rapid access to and use of semantic information, production and comprehension of complex prose, fine motor skills, and perceptual speed of verbal intelligence, and men routinely outscore women on tests that require transformations in visual or spatial memory, certain motor skills, spatiotemporal responding, and fluid reasoning in abstract mathematical and scientific domains (Halpern, 1997; Halpern et al., 2007). Indeed, group differences in performance on intelligence tests “are among the most thoroughly documented findings in psychology” (Suzuki & Valencia, 1997, p. 1104). Although the average difference between groups is considerably less than the average difference within groups, so that there is a huge amount of overlap between the groups, Terman was right when he noted that some groups perform better than others on intelligence tests. The question is why?

10.5.2.1 Tests and Test Takers

One possibility is that there is something wrong with the tests. In fact, there is now little doubt that the earliest intelligence tests asked questions whose answers were more likely to be known by members of one group (usually white Western Europeans) than by members of another. For example, when Binet and Simon asked students, “When anyone has offended you and asks you to excuse him, what ought you to do?,” they were looking for answers such as “accept the apology graciously.” Answers such as “demand three goats” would have been counted as wrong. But intelligence tests have come a long way in a century, and one would have to look hard to find questions on a modern intelligence test that have the same blatant cultural bias that Binet and Simon’s test did (Suzuki & Valencia, 1997). Moreover, group differences emerge even on those portions of intelligence tests that measure nonverbal skills, such as Raven’s Progressive Matrices Test (see Figure 10.4). It would be difficult to argue that the large differences between the average scores of different groups is due entirely—

How can the testing situation affect a person’s performance on an IQ test?

Of course, even when test questions are unbiased, testing situations may not be. For example, studies show that African American students perform more poorly on tests if they are asked to report their race at the top of the answer sheet, because doing so causes them to feel anxious about confirming racial stereotypes (Steele & Aronson, 1995) and anxiety naturally interferes with test performance (Reeve, Heggestad, & Lievens, 2009). European American students do not show the same effect when asked to report their race. When Asian American women are reminded of their gender, they perform unusually poorly on tests of mathematical skill, presumably because they are aware of stereotypes suggesting that women cannot do mathematics. But when the same women are instead reminded of their ethnicity, they perform unusually well on such tests, presumably because they are aware of stereotypes suggesting that Asians are especially good at mathematics (Shih, Pittinsky, & Ambady, 1999). Indeed, when women read an essay suggesting that mathematical ability is strongly influenced by genes, they perform more poorly on subsequent mathematics tests (Dar-

419

10.5.2.2 Environments and Genes

Biases in the testing situation may explain some of the between-

How can environmental factors help explain between-

There is broad agreement among scientists that environment plays a major role. For example, African American children have lower birth weights, poorer diets, higher rates of chronic illness, poorer medical care, attend worse schools, and are three times more likely than European American children to live in single-

What would it take to prove that behavioural and psychological differences between groups have a genetic origin? It would take the kind of evidence that scientists often find when they study the physical differences between groups. For example, people who have hepatitis C are often given a prescription for antiviral drugs, and European Americans typically benefit more from this treatment than African Americans do. Although physicians once thought this was because European Americans were more likely to take the medicine they were given, scientists have recently discovered a gene that makes people unresponsive to these antiviral drugs—

420

10.5.3 Improving Intelligence

Intelligence can be improved—

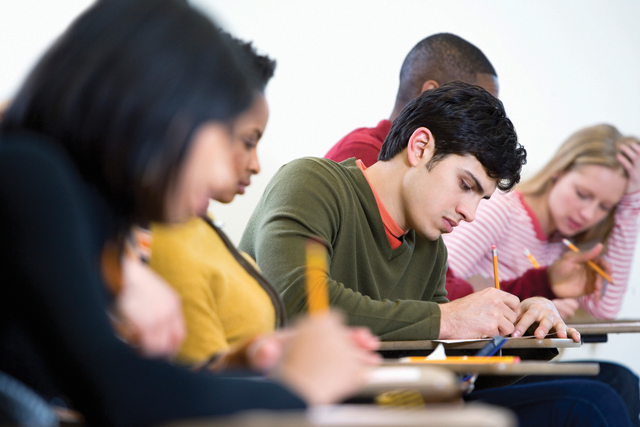

Perhaps all this will be simpler in the future. Cognitive enhancers are drugs that produce improvements in the psychological processes that underlie intelligent behaviour. For example, stimulants such as Ritalin (methylphenidate) and Adderall (mixed amphetamine salts) can enhance cognitive performance (Elliott et al., 1997; Halliday et al., 1994; McKetin et al., 1999), which is why there has been an increase in their use by healthy students over the past few years. Surveys suggest that almost 7 percent of students in American universities have used prescription stimulants for cognitive enhancement, and that on some campuses the number is as high as 25 percent (McCabe et al., 2005). Across Canadian university campuses, the percentages range from 1 to 33 percent (Ainsworth-

How might your children enhance their intelligence?

We should of course be worried about the abuse of these drugs. Nonetheless, the distinction between enhancing cognition by taking drugs and enhancing it by other means is not cut and dried. As one distinguished group of scientists (Greely et al., 2008, p. 703) recently concluded, “Drugs may seem distinctive among enhancements in that they bring about their effects by altering brain function, but in reality so does any intervention that enhances cognition. Recent research has identified beneficial neural changes engendered by exercise, nutrition and sleep, as well as instruction and reading.” In other words, if both drugs and exercise enhance cognition by altering the way the brain functions, then what exactly is the difference between them? Other scientists believe this question will soon be moot because cognitive enhancement will be achieved not by altering the brain’s chemistry in university, but by altering its basic structure at birth. By manipulating the genes that guide hippocampal development, scientists have created a strain of “smart mice” that have extraordinary memory and learning abilities, leading the researchers to conclude that “genetic enhancement of mental and cognitive attributes such as intelligence and memory in mammals is feasible” (Tang et al., 1999, p. 64). Although no one has yet developed a safe and powerful “smart pill” or “smart gene therapy,” many experts believe that this will happen in the next few years (Farah et al., 2004; Rose, 2002; Turner & Sahakian, 2006). When it does, we will need a whole lot of wisdom to know how to handle it.

421

OTHER VOICES: How Science Can Build a Better You

Intelligence is a highly prized commodity that buys people a lot of the good things in life. It can be increased by a solid education and a healthy diet, and everyone’s in favour of those things. But it can also be increased by drugs—

… Over the last couple of years during talks and lectures, I have asked thousands of people a hypothetical question that goes like this: “If I could offer you a pill that allowed your child to increase his or her memory by 25 percent, would you give it to them?”

The show of hands in this informal poll has been overwhelming, with 80 percent or more voting no.

Then I asked a follow-

“And what if all of the other kids are taking the pill?” I asked. The tittering stopped and nearly everyone voted yes.

No pill now exists that can boost memory by 25 percent. Yet neuroscientists tell me that pharmaceutical companies are testing compounds in early stage human trials that may enable patients with dementia and other memory-

More intriguing is the notion that a supermemory or attention pill might be used someday by those with critical jobs like pilots, surgeons, police officers—

For years, scientists have been manipulating genes in animals to make improvements in neural performance, strength and agility, among other augmentations. Directly altering human DNA using “gene therapy” in humans remains dangerous and fraught with ethical challenges. But it may be possible to develop drugs that alter enzymes and other proteins associated with genes for, say, speed and endurance or dopamine levels in the brain connected to improved neural performance.

Synthetic biologists contend that re-

Not all enhancements are high-

Ethical challenges for the coming Age of Enhancement include, besides basic safety questions, the issue of who would get the enhancements, how much they would cost, and who would gain an advantage over others by using them. In a society that is already seeing a widening gap between the very rich and the rest of us, the question of a democracy of equals could face a critical test if the well-

Still, the enhancements are coming, and they will be hard to resist. The real issue is what we do with them once they become irresistible.

From the New York Times, November 3, 2012 © 2012 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

422

Some groups outscore others on intelligence tests because (a) testing situations impair the performance of some groups more than others, and (b) some groups live in less healthful and stimulating environments.

There is no compelling evidence to suggest that between-

group differences in intelligence are due to genetic differences. The distinction between genetic and environmental influences on intelligence can be murky. For example, genes can influence an organism’s behaviour by determining which environments it is drawn to.

Intelligence is correlated with mental health, and gifted children are as well-

adjusted as their peers. Human intelligence can be temporarily increased by cognitive enhancers such as Ritalin and Adderall, and nonhuman intelligence has been permanently increased by genetic manipulation.