11.4 Adolescence: Minding the Gap

Between childhood and adulthood is an extended developmental stage that may not qualify for a “hood” of its own, but that is clearly distinct from the stages that come before and after. Adolescence is the period of development that begins with the onset of sexual maturity (about 11 to 14 years of age) and lasts until the beginning of adulthood (about 18 to 21 years of age). Unlike the transition from embryo to fetus or from infant to child, this transition is sudden and clearly marked. In just 3 or 4 years, the average adolescent gains about 18 kg and grows about 20 cm. For girls, all this growing starts at about the age of 10 and ends when they reach their full heights at about the age of 15.5. For boys it starts at about the age of 12 and ends at about the age of 17.5.

The beginnings of this growth spurt signals the onset of puberty, which refers to the bodily changes associated with sexual maturity. These changes involve primary sex characteristics, which are bodily structures that are directly involved in reproduction, for example, the onset of menstruation in girls and the enlargement of the testes, scrotum, and penis and the emergence of the capacity for ejaculation in boys. They also involve secondary sex characteristics, which are bodily structures that change dramatically with sexual maturity but that are not directly involved in reproduction, for example, the enlargement of the breasts and the widening of the hips in girls and the appearance of facial hair, pubic hair, underarm hair, and the lowering of the voice in both genders. This pattern of changes is caused by increased production of estrogen in girls and testosterone in boys.

How does the brain change at puberty?

Just as the body changes during adolescence, so too does the brain. For example, there is a marked increase in the growth rate of tissue connecting different regions of the brain just before puberty (Thompson et al., 2000). The Czech–

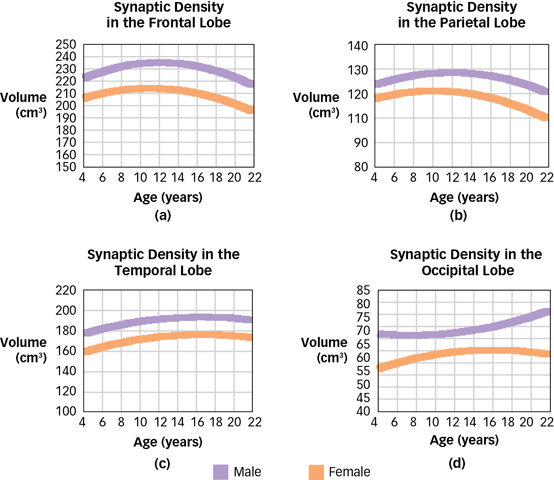

But the most important neural changes occur in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain associated with the ability to regulate emotions, and to control attention and behaviour. An infant’s brain forms many more new synapses than it actually needs, and by the time children are 2 years old they have about 15 000 synapses per neuron, which is roughly twice as many as the average adult (Huttenlocher, 1979). This early period of synaptic proliferation is followed by a period of synaptic pruning in which the connections that are not frequently used are eliminated. This is a clever system that allows the brain’s wiring to be determined in part by its experience in the world. Scientists used to think that this process ended early in life, but recent evidence suggests that the prefrontal cortex undergoes a second wave of synaptic proliferation just before puberty, and a second round of synaptic pruning during adolescence (Giedd et al., 1999). During this period, the prefrontal cortex also seems to be forming faster, more efficient connections with the rest of the brain (Paus, 2005). Clearly, the adolescent brain is a work in progress.

453

11.4.1 The Protraction of Adolescence

How has the onset of puberty changed over the last century?

The age at which puberty begins varies across individuals (e.g., people tend to reach puberty at about the same age as their same-

454

The increasingly early onset of puberty has important psychological consequences. Just two centuries ago, the gap between childhood and adulthood was relatively brief because people became physically mature at roughly the same time that they were ready to accept adult roles in society, and these roles did not normally require them to have extensive schooling. But in modern societies, people typically spend 3 to 10 years in school after they reach puberty. Thus, while the age at which people become physically adult has decreased, the age at which they are prepared or allowed to take on adult responsibilities has increased, and so the period between childhood and adulthood has become protracted. What are the consequences of a protracted adolescence?

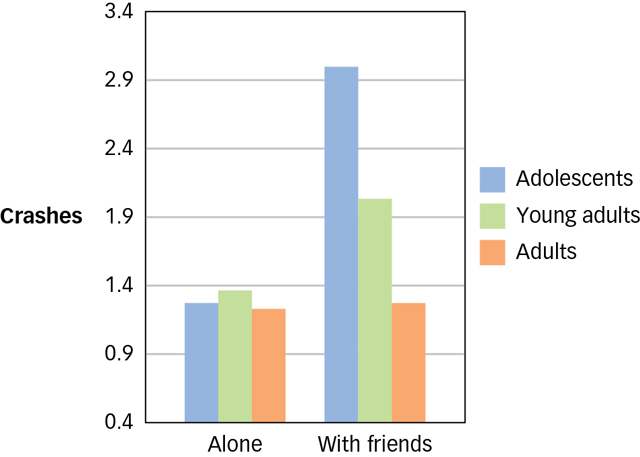

Adolescence is often characterized as a time of internal turmoil and external recklessness, and some psychologists have speculated that the protraction of adolescence is in part to blame for its sorry reputation (Moffitt, 1993). According to these theorists, adolescents are adults who have temporarily been denied a place in adult society, mostly through the school system and through restrictions on the types of work that adolescents in Western countries like Canada and the United States are permitted to do (Epstein, 2007a). American teenagers are subjected to 10 times as many restrictions as adults, and twice as many restrictions as American Marines on active duty or incarcerated felons (Epstein, 2007a). As such, they feel especially compelled to do things to protest these restrictions and demonstrate their adulthood, such as smoking, drinking, using drugs, having sex, and committing crimes. In a sense, adolescents are people who are forced to live in a strange gap between two worlds, and the pathologies of adolescence are partly a result of this predicament. As one researcher noted, “Trapped in the frivolous world of peer culture, they learn virtually everything they know from one another rather than from the people they are about to become. Isolated from adults and wrongly treated like children, it is no wonder that some teens behave, by adult standards, recklessly or irresponsibly” (Epstein, 2007b).

Are adolescent problems inevitable?

But the storm and stress of adolescence is by no means inevitable (Steinberg & Morris, 2001). Research suggests that the “moody adolescent” who is a victim of “raging hormones” is largely a myth. Adolescents are no moodier than children (Buchanan, Eccles, & Becker, 1992), and fluctuations in their hormone levels have only a tiny impact on their moods (Brooks-

455

11.4.2 Sexuality

What makes adolescence especially difficult?

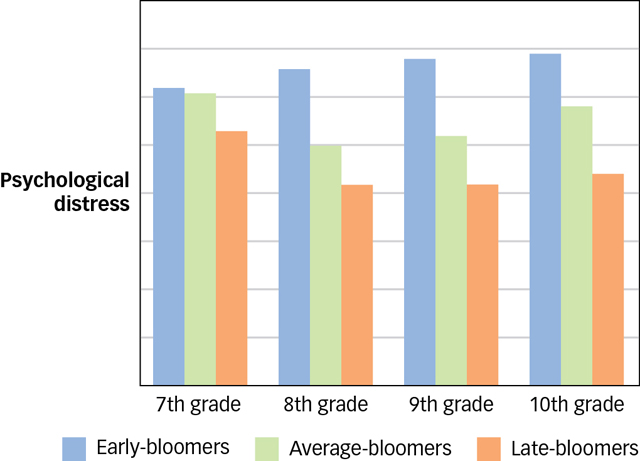

Puberty can be a difficult time, but it is especially difficult for girls who reach it earlier than their peers. These girls are more likely to experience a range of negative consequences, from distress and depression to delinquency and disease (Mendle, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2007) (see FIGURE 11.13). This happens for several reasons (Ge & Natsuaki, 2009). First, early bloomers do not have as much time as their peers do to develop the skills necessary to cope with adolescence (Petersen & Grockett, 1985), but because they look so mature, people expect them to act like adults. In other words, early puberty creates unrealistic expectations and demands that the adolescent may have trouble fulfilling. Second, early blooming girls draw the attention of older men, who may lead them into a variety of unhealthy activities (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996). Some research suggests that for girls, the timing of puberty has a greater influence on emotional and behavioural problems than does the occurrence of puberty itself (Buchanan et al., 1992). The timing of puberty does not have such consistent effects on boys: Some studies suggest that early maturing boys do better than their peers, some show they do worse, and some show that there is no difference at all (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001). Interestingly, recent research suggests that for boys, tempo, the speed with which they transition from the first to the last stages of puberty, may be a better predictor of negative outcomes than is timing (Mendle et al., 2010).

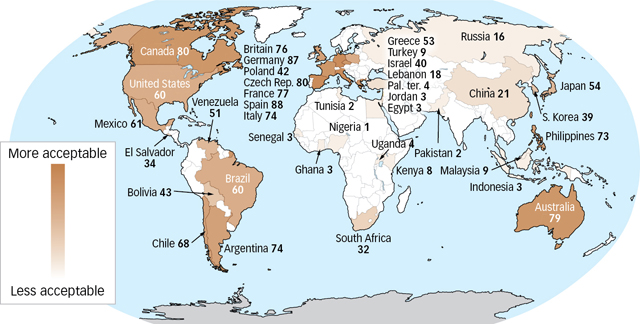

For some adolescents, puberty is additionally complicated by the fact that they are attracted to members of the same sex. Most gay men report having become aware of their sexual orientation between the ages of 6 and 18, and most lesbians report having become aware between the ages of 11 and 26 (Calzo et al., 2011). Not only does their sexual orientation make gay adolescents different from the vast majority of their peers (a mere 2 percent of Canadian adults identify themselves as lesbian, gay, or bisexual) (Statistics Canada, 2004), but it can also subject them to disapproval from family, friends, and community. In a recent survey (Pew Research Center Global Attitudes Project, 2013), almost 1 in 5 Canadians said that homosexuality is a way of life that should not be accepted by society, and Canada is much more accepting of homosexuality than are many other nations (see FIGURE 11.14). In some countries, gay citizens are imprisoned or sentenced to death.

456

Given so much social disapproval, it is little wonder that the happiness and well-

Is sexual orientation a matter of nature or nurture?

What determines whether a person’s sexuality is primarily oriented toward the same or the opposite sex? For a long time, psychologists believed that a person’s sexual orientation depended primarily on his or her upbringing. For example, psychoanalytic theorists claimed that boys who grow up with a domineering mother and a submissive father are less likely to identify with their father and are therefore more likely to become homosexual. Okay. Nice theory. But the fact is that scientific research has failed to identify any aspect of parenting that has a significant impact on a child’s ultimate sexual orientation (Bell, Weinberg, & Hammersmith, 1981). Perhaps the most telling fact is that children raised by homosexual couples and children raised by heterosexual couples are equally likely to become heterosexual adults (Patterson, 1995). There is also little support for the idea that a person’s early sexual encounters have a lasting impact on his or her sexual orientation (Bohan, 1996).

So what does determine a person’s sexual orientation? There is now considerable evidence to suggest that biology plays the major role. Not only do gay people have a larger proportion of gay siblings than do heterosexuals (Bailey et al., 1999), but the identical twin of a gay man (with whom he shares 100 percent of his genes) has a 50 percent chance of being gay, whereas the fraternal twin or non-

Of course, genes and prenatal biology cannot be the sole determinant of a person’s sexual orientation because many homosexual men and women have identical twins who shared both their fetal environment and their genes, and who are nonetheless heterosexual. There must be other factors and, at present, we just do not know what they are. But one thing we do know is that regardless of what leads people to have a particular sexual orientation, there is no evidence that it can be changed by so-

457

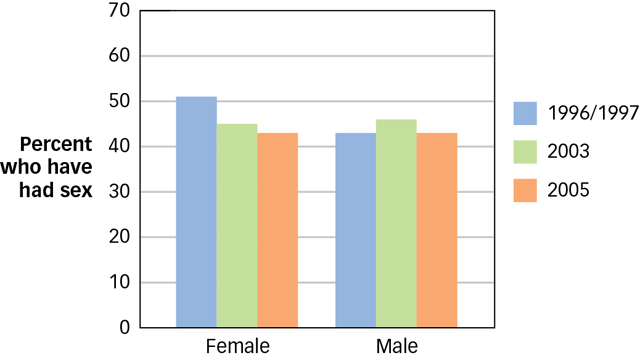

In 2005, 43% of Canadian teens aged 15 to 19 reported having had sexual intercourse at least once, with no difference between men and women (Rotermann, 2008). Interestingly, the rate at which young Canadian women engage in sex is dropping. In 1996/1997, 51% of young women aged 15 to 19 reported having sexual intercourse at least once, compared to 43% in 2005. The proportion of adolescents reporting experience with sexual intercourse was higher among 18 to 19 year olds (approximately 67%) than among 15 to 17 year olds (approximately 33%) and was higher in Quebec (58%) than in the other Canadian provinces (see TABLE 11.2). FIGURE 11.15 shows the general trends in sexual activity among male and female teens from 1996 to 2005.

|

|

1996/1997 (%) |

2003 (%) |

2005 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age Group |

|

|

|

|

15 to 17 |

32 |

30 |

29 |

|

18 to 19 |

70 |

68 |

65 |

|

Province |

|

|

|

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

46 |

54 |

49 |

|

Prince Edward Island |

37 |

52 |

35 |

|

Nova Scotia |

31 |

49 |

49 |

|

New Brunswick |

43 |

52 |

43 |

|

Quebec |

59 |

62 |

58 |

|

Ontario |

41 |

40 |

37 |

|

Manitoba |

39 |

43 |

39 |

|

Saskatchewan |

54 |

39 |

43 |

|

Alberta |

44 |

39 |

39 |

|

British Columbia |

47 |

37 |

40 |

Why do many adolescents make unwise choices about sex?

The best scientific evidence suggests that sex education leads teens to delay having sex for the first time, increases the likelihood they will use birth control when they do have sex, and lowers the likelihood that they will get pregnant or catch a sexually transmitted disease (Mueller, Gavin, & Kulkarni, 2008; Satcher, 2001). Although young people between the ages of 15 to 24 years have among the highest rates of sexually transmitted infections, condom use is increasing: in 2003, 62% of sexually active people aged 15 to 24 reported than they had used condoms the last time they had intercourse. This proportion increased to 68% in 2009–

458

11.4.3 Parents and Peers

“Who am I?” is a question asked by amnesiacs and adolescents, who tend to ask it for different reasons. Children’s views of themselves and their world are tightly tied to the views of their parents, but puberty creates a new set of needs that begins to snip away at those bonds by orienting adolescents toward peers rather than parents. Psychologist Erik Erikson (1959) characterized each stage of life by the major task confronting the individual at that stage. His stages of psychosocial development (shown in TABLE 11.3) borrow from the work of Sigmund Freud, and suggest that the major task of adolescence is the development of an adult identity. Whereas children define themselves almost entirely in terms of their relationships with parents and siblings, adolescence marks a shift in emphasis from family relations to peer relations.

|

According to Erikson, at each “stage” of development a “key event” creates a challenge or “crisis” that a person can resolve positively or negatively. |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ages |

Stage |

Key Event |

Crisis |

Positive Resolution |

|

1. Birth to 12– |

Oral– |

Feeding |

Trust vs. mistrust |

Child develops a belief that the environment can be counted on to meet his or her basic physiological and social needs. |

|

2. 18 months to 3 years |

Muscular– |

Toilet training |

Autonomy vs. shame/doubt |

Child learns what he or she can control and develops a sense of free will and corresponding sense of regret and sorrow for inappropriate use of self- |

|

3. 3– |

Locomotor |

Independence |

Initiative vs. guilt |

Child learns to begin action, to explore, to imagine, and to feel remorse for actions. |

|

4. 6– |

Latency |

School |

Industry vs. inferiority |

Child learns to do things well or correctly in comparison to a standard or to others. |

|

5. 12– |

Adolescence |

Peer relationships |

Identity vs. role confusion |

Adolescent develops a sense of self in relationship to others and to own internal thoughts and desires. |

|

6. 19– |

Young adulthood |

Love relationships |

Intimacy vs. isolation |

Person develops the ability to give and receive love; begins to make long- |

|

7. 40– |

Middle adulthood |

Parenting |

Generativity vs. stagnation |

Person develops interest in guiding the development of the next generation. |

|

8. 65 to death |

Maturity |

Reflection on and acceptance of one’s life |

Ego integrity vs. despair |

Person develops a sense of acceptance of life as it was lived and the importance of the people and relationships that the individual developed over the life span. |

How do family and peer relationships change during adolescence?

Two things can make this shift difficult. First, children cannot choose their parents, but adolescents can choose their peers. As such, adolescents have the power to shape themselves by joining groups that will lead them to develop new values, attitudes, beliefs, and perspectives. In a sense, the adolescent has the opportunity to invent the adult he or she will soon become, and the responsibility this opportunity entails can be overwhelming. Second, as adolescents strive for greater autonomy, their parents naturally rebel. For instance, parents and adolescents tend to disagree about the age at which certain adult behaviours—

459

Adolescents pull away from their parents, but more importantly, they move toward their peers. Studies show that across a wide variety of cultures, historical epochs, and even species, peer relations evolve in a similar way (Dunphy, 1963; Weisfeld, 1999). Young adolescents initially form groups or “cliques” with same-

Studies show that throughout adolescence, people spend increasing amounts of time with opposite-

Adolescence is a stage of development that is distinct from those stages that come before and after it. It begins with a growth spurt and with puberty, the onset of sexual maturity of the human body. Puberty is occurring earlier than ever before, and the entrance of young people into adult society is occurring later.

During this “in-

between stage,” adolescents are somewhat more prone to do things that are risky or illegal, but they rarely inflict serious or enduring harm on themselves or others. During adolescence, sexual interest intensifies and, in some cultures, sexual activity begins. Sexual activity typically follows a script, many aspects of which are standard across cultures. Although most people are attracted to members of the opposite sex, some are not, and research suggests that biology plays a key role in determining a person’s sexual orientation.

As adolescents seek to develop their adult identities, they seek increasing autonomy from their parents and become more peer-

oriented, forming single- sex cliques, followed by mixed- sex cliques, and finally pairing off as couples.

460