14.4 Stress Management: Dealing with It

Most university students (92 percent) say they occasionally feel overwhelmed by the tasks they face, and over a third say they have dropped courses or received low grades in response to severe stress (Duenwald, 2002). No doubt you are among the lucky 8 percent who are entirely cool and report no stress. But just in case you are not, you may be interested in our exploration of stress management techniques: ways to counteract psychological and physical stress reactions directly by managing your mind and body, and ways to sidestep stress by managing your situation.

14.4.1 Mind Management

Stressful events are magnified in the mind. If you fear public speaking, for example, just the thought of an upcoming presentation to a group can create anxiety. And if you do break down during a presentation (going blank, for example, or blurting out something embarrassing), intrusive memories of this stressful event could echo in your mind afterward. A significant part of stress management, then, is control of the mind.

14.4.1.1 Repressive Coping

Controlling your thoughts is not easy, but some people do seem to be able to banish unpleasant thoughts from the mind. This style of dealing with stress, called repressive coping, is characterized by avoiding situations or thoughts that are reminders of a stressor and maintaining an artificially positive viewpoint. Everyone has some problems, of course, but repressors are good at deliberately ignoring them (Barnier, Levin, & Maher, 2004). So, for example, when repressors suffer a heart attack, they are less likely than other people to report intrusive thoughts of their heart problems in the days and weeks that follow (Ginzburg, Solomon, & Bleich, 2002).

When is it useful to avoid stressful thoughts and when is avoidance a problem?

Like Elizabeth Smart, who for years after her rescue focused in interviews on what was happening in her life now, rather than repeatedly discussing her past in captivity, people often rearrange their lives in order to avoid stressful situations. Many victims of rape, for example, not only avoid the place where the rape occurred, but may move away from their home or neighborhood (Ellis, 1983). Anticipating and attempting to avoid reminders of the traumatic experience, they become wary of strangers, especially men who resemble the assailant, and they check doors, locks, and windows more frequently than before. It may make sense to try to avoid stressful thoughts and situations if you are the kind of person who is good at putting unpleasant thoughts and emotions out of mind (Coifman et al., 2007). For some people, however, the avoidance of unpleasant thoughts and situations is so difficult that it can turn into a grim preoccupation (Parker & McNally, 2008; Wegner & Zanakos, 1994). For those who cannot avoid negative emotions effectively, it may be better to come to grips with them. This is the basic idea of rational coping.

14.4.1.2 Rational Coping

What are the three steps in rational coping?

Rational coping involves facing the stressor and working to overcome it. This strategy is the opposite of repressive coping and so may seem to be the most unpleasant and unnerving thing you could do when faced with stress. It requires approaching, rather than avoiding, a stressor in order to lessen its longer-

562

When the trauma is particularly intense, rational coping may be difficult to undertake. In rape trauma, for example, even accepting that the rape happened takes time and effort; the initial impulse is to deny the event and try to live as though it had never occurred. Psychological treatment may help during the exposure step by helping victims to confront and think about what happened. Using a technique called prolonged exposure, rape survivors relive the traumatic event in their imagination by recording a verbal account of the event and then listening to the recording daily. In one study, rape survivors were instructed to seek out objectively safe situations that caused them anxiety or that they had avoided. This sounds like bitter medicine indeed, but it is remarkably effective, producing significant reductions in anxiety and symptoms of post-

The third element of rational coping involves coming to an understanding of the meaning of the stressful events. A trauma victim may wonder again and again: Why me? How did it happen? Why? Survivors of incest frequently voice the desire to make sense of their trauma (Silver, Boon, & Stones, 1983), a process that is difficult, even impossible, during bouts of suppression and avoidance.

14.4.1.3 Reframing

Changing the way you think is another way to cope with stressful thoughts. Reframing involves finding a new or creative way to think about a stressor that reduces its threat. If you experience anxiety at the thought of public speaking, for example, you might reframe by shifting from thinking of an audience as evaluating you to thinking of yourself as evaluating them, and this might make speech giving easier.

Reframing can be an effective way to prepare for a moderately stressful situation, but if something like public speaking is so stressful that you cannot bear to think about it until you absolutely must, the technique may not be usable. Stress inoculation training (SIT) is a reframing technique that helps people to cope with stressful situations by developing positive ways to think about the situation. For example, in one study, people who had difficulty controlling their anger were trained to rehearse and reframe their thoughts with phrases like these: “Just roll with the punches, do not get bent out of shape,” “You do not need to prove yourself,” “I am not going to let him get to me,” “It is really a shame he has to act like this,” and “I will just let him make a fool of himself.” Anger-

How has writing about stressful events been shown to be helpful?

Reframing can take place spontaneously if people are given the opportunity to spend time thinking and writing about stressful events. In an important series of studies, Jamie Pennebaker (1989) found that the physical health of university students improved after they spent a few hours writing about their deepest thoughts and feelings. Compared with students who had written about something else, members of the self-

563

14.4.2 Body Management

Stress can express itself as tension in your neck muscles, back pain, a knot in your stomach, sweaty hands, or the harried face you glimpse in the mirror. Because stress so often manifests itself through bodily symptoms, bodily techniques such as meditation, relaxation therapy, biofeedback, and aerobic exercise are useful in its management.

14.4.2.1 Meditation

Meditation is the practice of intentional contemplation. Techniques of meditation are associated with a variety of religious traditions and are also practised outside religious contexts. The techniques vary widely. Some forms of meditation call for attempts to clear the mind of thought, others involve focusing on a single thought (e.g., thinking about a candle flame), and still others involve concentration on breathing or on a mantra (a repetitive sound such as om). At a minimum, the techniques have in common a period of quiet.

What are some positive outcomes of meditation?

Time spent meditating can be restful and revitalizing. Beyond these immediate benefits, many people also meditate in an effort to experience deeper or transformed consciousness. Whatever the reason, meditation does appear to have positive psychological effects (Hölzel et al., 2011). Many believe it does so, in part, by improving control over attention. The focus of many forms of meditation, such as mindfulness meditation, is on teaching ourselves how to remain focused on, and accepting of, our immediate experience. Interestingly, experienced meditators show deactivation in the default mode network (which is associated with mind wandering; see Figure 5.6 in the Consciousness chapter) during meditation relative to non-

14.4.2.2 Relaxation

Imagine for a moment that you are scratching your chin. Do not actually do it; just think about it and notice that your body participates by moving ever so slightly, tensing and relaxing in the sequence of the imagined action. Edmund Jacobson (1932) discovered these effects with electromyography (EMG), a technique used to measure the subtle activity of muscles. A person asked to imagine rowing a boat or plucking a flower from a bush would produce slight levels of tension in the muscles involved in performing the act. Jacobson also found that thoughts of relaxing the muscles sometimes reduced EMG readings when people did not even report feeling tense. Our bodies respond to all the things we think about doing every day. These thoughts create muscle tension even when we think we are doing nothing at all.

564

These observations led Jacobson to develop relaxation therapy, a technique for reducing tension by consciously relaxing muscles of the body. A person in relaxation therapy may be asked to relax specific muscle groups one at a time or to imagine warmth flowing through the body or to think about a relaxing situation. This activity draws on a relaxation response, a condition of reduced muscle tension, cortical activity, heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure (Benson, 1990). Basically, as soon as you get in a comfortable position, quiet down, and focus on something repetitive or soothing that holds your attention, you relax.

Relaxing on a regular basis can reduce symptoms of stress (Carlson & Hoyle, 1993) and even reduce blood levels of cortisol, the biochemical marker of the stress response (McKinney et al., 1997). For example, in individuals who are suffering from tension headache, relaxation reduces the tension that causes the headache; in individuals with cancer, relaxation makes it easier to cope with stressful treatments for the disease; in individuals with stress-

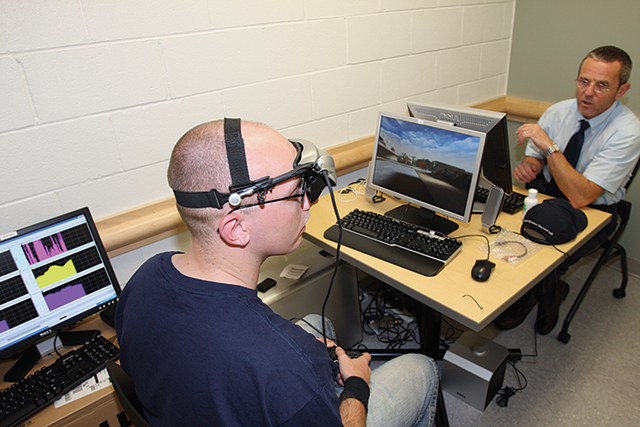

14.4.2.3 Biofeedback

Would not it be nice if, instead of having to learn to relax, you could just flip a switch and relax as fast as possible? Biofeedback, the use of an external monitoring device to obtain information about a bodily function and possibly gain control over that function, was developed with this goal of high-

How does biofeedback work?

Biofeedback can help people control physiological functions they are not likely to become aware of in other ways. For example, you probably have no idea right now what brain-

Recent studies suggest that EEG biofeedback (or neurofeedback) is moderately successful in treating brain-

14.4.2.4 Aerobic Exercise

A jogger nicely decked out in a neon running suit bounces in place at the crosswalk and then springs away when the signal changes. It is tempting to assume that this jogger is the picture of psychological health: happy, unstressed, and even downright exuberant. As it turns out, the stereotype is true: Studies indicate that aerobic exercise (exercise that increases heart rate and oxygen intake for a sustained period) is associated with psychological well-

565

What are the benefits of exercise?

To try to tease apart causal factors, researchers have randomly assigned people to aerobic exercise activities and no-

The reasons for these positive effects are unclear. Researchers have suggested that the effects result from increases in the body’s production of neurotransmitters such as serotonin, which can have a positive effect on mood (as discussed in the Neuroscience and Behaviour chapter) or from increases in the production of endorphins (the endogenous opioids discussed in the Neuroscience and Behaviour, and Consciousness chapters) (Jacobs, 1994).

Beyond boosting positive mood, exercise also stands to keep you healthy into the future. Current Canadian government recommendations suggest that 150 minutes a week of exercise, in bouts of 10 minutes or longer, will improve fitness and strength and lead to feeling better (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2011b). Perhaps the simplest thing you can do to improve your happiness and health, then, is to participate regularly in an aerobic activity. Pick something you find fun: Sign up for a dance class, get into a regular basketball game, or start paddling a canoe—

14.4.3 Situation Management

After you have tried to manage stress by managing your mind and managing your body, what is left to manage? Look around and you will notice a whole world out there. Perhaps that could be managed as well. Situation management involves changing your life situation as a way of reducing the impact of stress on your mind and body. Ways to manage your situation can include seeking out social support, religious or spiritual practice, and finding a place for humour in your life.

14.4.3.1 Social Support

The wisdom of the National Safety Council’s first rule—

566

An intimate partner can help you remember to get your exercise and follow your doctor’s orders, and together you will probably follow a more healthy diet than you would all alone with your snacks.

Talking about problems with friends and family can offer many of the benefits of professional psychotherapy, usually without the hourly fees.

Sharing tasks and helping each other when times get tough can reduce the amount of work and worry in each other’s lives.

The helpfulness of strong social bonds, though, transcends mere convenience. Lonely people are more likely than others to be stressed and depressed (Baumeister & Leary, 1995), and they can be more susceptible to illness because of lower-

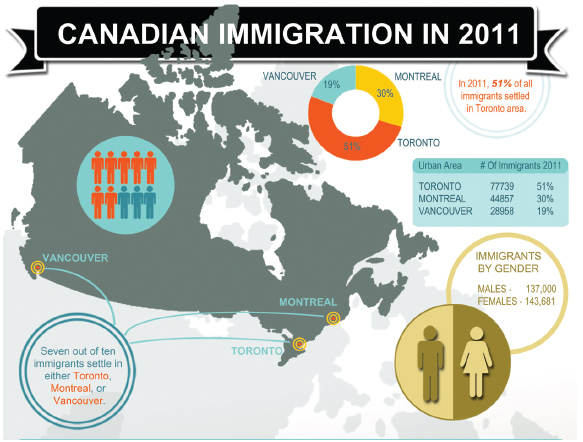

CULTURE & COMMUNITY: Oh Canada, Our (New) Home and (Non-)Native Land…

According to the 2006 Canadian census, immigrants accounted for 24 percent of the Canadian population and over one million immigrants arrived in Canada between 2001 and 2006 (Milan, 2011). Three quarters of these immigrants are from Asia, with China and India being the major source countries. Of course, this means that many immigrants have neither English nor French as their mother tongue. Do they find immigration stressful? To some extent, they must: Immigration generally involves leaving friends, extended family, and everything that is familiar behind. The language and culture is also alien, and immigrants often arrive without a guaranteed source of income. Given potential trouble with communication, lack of knowledge of local customs, decreases in social support, and financial uncertainty that accompany immigration, one might expect a higher rate of mental illness amongst new immigrants to Canada.

In fact, the opposite appears to be true: Immigrants are more likely to be in better health than Canadian-

Unfortunately, this rosy picture fades quickly—

567

Why is the hormone oxytocin a health advantage for women?

The value of social support in protecting against stress may be very different for women and men: Whereas women seek support under stress, men are less likely to do so. The fight-

14.4.3.2 Religious Experiences

National polls indicate that about 72 percent of Canadians believe in a god, and many who do, pray at least once per day. Many who believe in a higher power believe that their faith will be rewarded in an afterlife—

Why are religiosity and spirituality associated with health benefits?

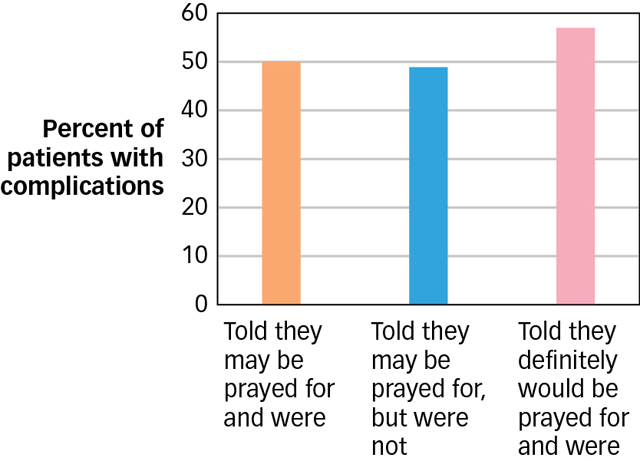

Why do people who endorse religiosity or spirituality have better mental and physical health? Is it divine intervention? Several testable ideas have been proposed. Engagement in religious or spiritual practices, such as attendance at weekly religious services, may lead to the development of a stronger and more extensive social network, which has well-

568

14.4.3.3 Humour

How does humour mitigate stress?

It would be nice to laugh at your troubles and move on. Most of us recognize that humour can diffuse unpleasant situations and bad feelings, and it makes sense that bringing some fun into your life could help to reduce stress. The extreme point of view on this topic is staked out in self-

There is a kernel of truth to the theory that humour can help us cope with stress. For example, humour can reduce sensitivity to pain and distress, as researchers found when they subjected volunteers to an overinflated blood pressure cuff. Participants were more tolerant of the pain during a laughter-

Humour can also reduce the time needed to calm down after a stressful event. For example, men viewing a highly stressful film about three industrial accidents were asked to narrate the film aloud, either by describing the events seriously or by making their commentary as funny as possible. Although men in both groups reported feeling tense while watching the film and showed increased levels of sympathetic nervous arousal (increased heart rate and skin conductance, decreased skin temperature), those looking for humour in the experience bounced back to normal arousal levels more quickly than did those in the serious story group (Newman & Stone, 1996).

If laughter and fun can alleviate stress quickly in the short term, do the effects accumulate to improve health and longevity? Sadly, the evidence suggests not (Provine, 2000). A study titled Do Comics Have the Last Laugh? tracked the longevity of comedians in comparison to other entertainers and nonentertainers (Rotton, 1992). It was found that the comedians died younger—

The management of stress involves strategies for influencing the mind, the body, and the situation.

People try to manage their minds by trying to suppress stressful thoughts or avoid the situations that produce them, by rationally coping with the stressor, and by reframing.

Body management strategies involve attempting to reduce stress symptoms through meditation, relaxation, biofeedback, and aerobic exercise.

Overcoming stress by managing your situation can involve seeking out social support, engaging in religious experiences, or attempting to find humour in stressful events.