10.4 Adulthood: Change We Can’t Believe In

Adulthood is the stage of development that begins around 18 to 21 years and ends at death. Because physical change slows from a gallop to a crawl, many of us think of adulthood as the destination to which the process of development finally delivers us, and that once we’ve arrived, our journey is pretty much complete. Nothing could be further from the truth. A whole host of physical, cognitive, and emotional changes take place between our first legal beer and our last legal breath.

adulthood

The stage of development that begins around 18 to 21 years and ends at death.

340

Changing Abilities

The early 20s are the peak years for health, stamina, vigor, and prowess, and because our psychology is so closely tied to our biology, these are also the years during which most cognitive abilities are sharpest. At this very moment, you probably see farther, hear better, and remember more accurately than you ever will again. Enjoy it. Somewhere between the ages of 26 and 30, you will begin the slow and steady decline that will not end until you do. Just 10 or 15 years after puberty, your body will begin to break down in almost every way. Your muscles will be replaced by fat, your skin will become less elastic, your hair will thin and your bones will weaken, your sensory abilities will become less acute, and your brain cells will die at an accelerated rate. Eventually, if you are a woman, your ovaries will stop producing eggs, and you will become infertile. Eventually, if you are a man, your erections will be softer and fewer and farther between. Indeed, other than being more resistant to colds and less sensitive to pain, your elderly body just won’t work as well as your youthful body does.

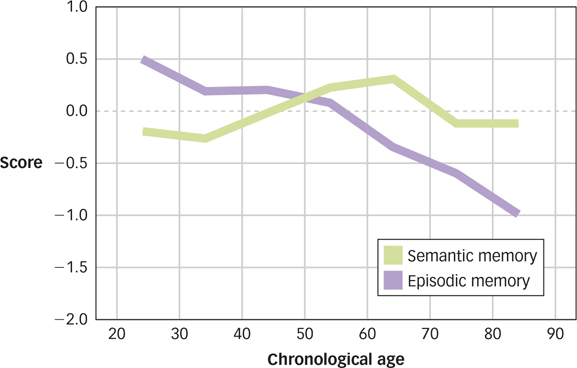

But don’t worry, the news gets worse. Because as these physical changes accumulate, they will begin to have measurable psychological consequences (Salthouse, 2006; see FIGURE 10.12). For instance, as you age, your prefrontal cortex will deteriorate more quickly than the other areas of your brain (Raz, 2000), and you will experience a noticeable decline on cognitive tasks that require effort, initiative, or strategy. Although your memory will worsen in general, you will experience more decline in working memory (the ability to hold information “in mind”) than in long-

What physical and psychological changes are associated with adulthood?

DATA VISUALIZATION

Cognitive Decline with Age

www.macmillanhighered.com/

But not all the news is bad. Even though your cognitive machinery will get rustier, research suggests that you will partially compensate by using it much more skillfully (Bäckman & Dixon, 1992; Salthouse, 1987). Older chess players remember chess positions much more poorly than younger players do, but they play just as well because they learn to search the board more efficiently (Charness, 1981). Older typists react more slowly than younger typists do, but they type just as quickly and accurately because they are better at anticipating the next word in spoken or written text (Salthouse, 1984). All of this suggests that older adults are using the skills they developed over a lifetime to compensate for the age-

How do adults compensate for their declining abilities?

341

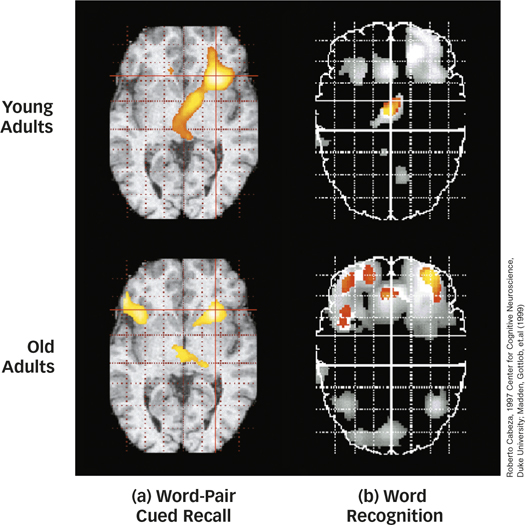

Even the brain changes the way it does business. As you know from the Neuroscience and Behavior chapter, brains are differentiated—

Changing Goals

So one reason why Grandpa can’t find his car keys is that his prefrontal cortex doesn’t work as well as it used to. But another reason is that the location of car keys just isn’t the sort of thing that grandpas spend their precious time memorizing (Haase, Heckhausen, & Wrosch, 2013). According to socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen & Turk-

How do informational goals change in adulthood?

342

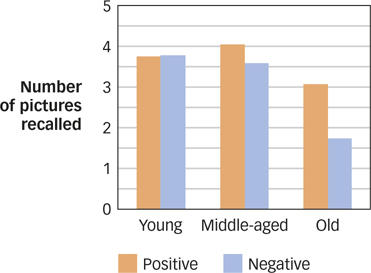

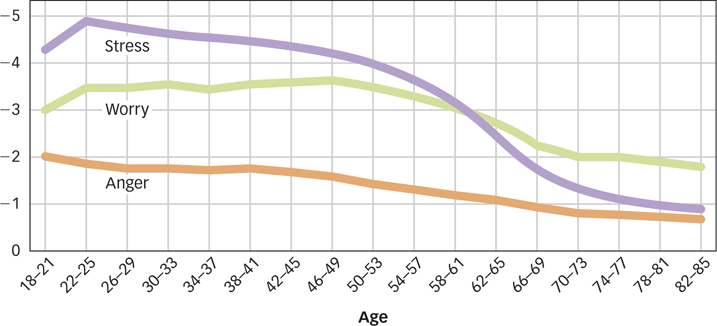

That’s one of the reasons why older people are much worse than younger people when they try to remember a series of unpleasant faces (see FIGURE 10.14), but only slightly worse when they try to remember a series of pleasant faces (Mather &Carstensen, 2003). Indeed, compared to younger adults, older adults are generally better at sustaining positive emotions and curtailing negative ones (Isaacowitz, 2012; Isaacowitz & Blanchard-

Is late adulthood a happy or unhappy time for most people?

Because having a short future orients people toward emotionally satisfying rather than intellectually profitable experiences, older adults become more selective about their interaction partners, choosing to spend time with family and a few close friends rather than with a large circle of acquaintances. One study monitored a group of people from the 1930s to the 1990s and found that the rate of interaction with acquaintances declined from early to middle adulthood, but the rate of interaction with spouses, parents, and siblings remained stable or increased (Carstensen, 1992). “Let’s go meet some new people” isn’t something that most 60-

343

Changing Roles

The psychological separation from parents that begins in adolescence usually becomes a physical separation in adulthood. In virtually all human societies, young adults leave home, get married, and have children of their own. The average college-

But do marriage and children really make us happy? Research shows that married people live longer, have more frequent sex (and enjoy that sex more), and earn several times as much money as unmarried people do (Waite, 1995). Given these differences, it is no surprise that married people report being happier than unmarried people—

What does research say about marriage, children, and happiness?

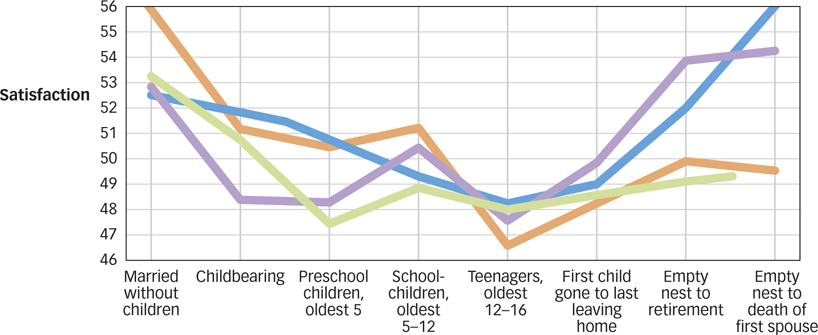

Children are another story. In general, research suggests that children do not increase their parents’ happiness, and may even decrease it (DiTella, MacCulloch, & Oswald, 2003; Simon, 2008; Senior, 2014). For example, parents typically report lower marital satisfaction than do nonparents—

344

Other Voices: You Are Going to Die

You Are Going to Die

Human development begins at conception and ends at death. Most of us would rather think about the conception part. Getting old seems scary and depressing, and one of the reasons why we send elderly people to retirement homes is so we don’t have to watch as they wrinkle and wither and die. The essayist Tim Kreider (2013) thinks this is a terrible loss—

My sister and I recently toured the retirement community where my mother has announced she’ll be moving. I have been in some bleak clinical facilities for the elderly where not one person was compos mentis and I had to politely suppress the urge to flee, but this was nothing like that. It was a very cushy modern complex housed in what used to be a seminary, with individual condominiums with big kitchens and sun rooms, equipped with fancy restaurants, grills and snack bars, a fitness center, a concert hall, a library, an art room, a couple of beauty salons, a bank and an ornate chapel of Italian marble. You could walk from any building in the complex to another without ever going outside, through underground corridors and glass-

At all times of major life crisis, friends and family will crowd around and press upon you the false emotions appropriate to the occasion. “That’s so great!” everyone said of my mother’s decision to move to an assisted-

My sadness is purely selfish, I know. My friends are right; this was all Mom’s idea, she’s looking forward to it, and she really will be happier there. But it also means losing the farm my father bought in 1976, where my sister and I grew up, where Dad died in 1991. We’re losing our old phone number, the one we’ve had since the Ford administration, a number I know as well as my own middle name. However infrequently I go there, it is the place on earth that feels like home to me, the place I’ll always have to go back to in case adulthood falls through. I hadn’t realized, until I was forcibly divested of it, that I’d been harboring the idea that someday, when this whole crazy adventure was over, I would at some point be nine again, sitting around the dinner table with Mom and Dad and my sister. And beneath it all, even at age 45, there is the irrational, little-

Plenty of people before me have lamented the way that we in industrialized countries regard our elderly as unproductive workers or obsolete products, and lock them away in institutions instead of taking them into our own homes out of devotion and duty. Most of these critiques are directed at the indifference and cruelty thus displayed to the elderly; what I wonder about is what it’s doing to the rest of us.

Segregating the old and the sick enables a fantasy, as baseless as the fantasy of capitalism’s endless expansion, of youth and health as eternal, in which old age can seem to be an inexplicably bad lifestyle choice, like eating junk food or buying a minivan, that you can avoid if you’re well-

We don’t see old or infirm people much in movies or on TV. We love explosive gory death onscreen, but we’re not so enamored of the creeping, gray, incontinent kind. Aging and death are embarrassing medical conditions, like hemorrhoids or eczema, best kept out of sight. Survivors of serious illness or injuries have written that, once they were sick or disabled, they found themselves confined to a different world, a world of sick people, invisible to the rest of us. Denis Johnson writes in his novel Jesus’ Son: “You and I don’t know about these diseases until we get them, in which case we also will be put out of sight.”

My own father died at home, in what was once my childhood bedroom. He was, in this respect at least, a lucky man. Almost everyone dies in a hospital now, even though absolutely nobody wants to, because by the time we’re dying all the decisions have been taken out of our hands by the well, and the well are without mercy. Of course we hospitalize the sick and the old for some good reasons (better care, pain relief), but I think we also segregate the elderly from the rest of society because we’re afraid of them, as if age might be contagious. Which, it turns out, it is.

… You are older at this moment than you’ve ever been before, and it’s the youngest you’re ever going to get. The mortality rate is holding at a scandalous 100 percent. Pretending death can be indefinitely evaded with hot yoga or a gluten-

Just yesterday my mother sent me a poem she first read in college—

Do you agree with Kreider: Do we do a disservice to the young when we segregate the old?

From the New York Times, January 20, 2013. © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited. http:/

345

Does all of this mean that people would be happier if they didn’t have children? Not necessarily. Because researchers cannot randomly assign people to be parents or nonparents, studies of the effects of parenthood are necessarily correlational. People who want children and have children may be somewhat less happy than people who neither want them nor have them, but it is possible that people who want children would be even less happy if they didn’t have them. What does seem clear is that raising children is a challenging job that people find most rewarding when they’re not in the middle of doing it.

SUMMARY QUIZ [10.4]

Question 10.11

| 1. | The peak years for health, stamina, vigor, and prowess are |

- childhood.

- the early teens.

- the early 20s.

- the early 30s.

c.

Question 10.12

| 2. | Data suggest that, for most people, the last decades of life are |

- characterized by an increase in negative emotions.

- spent attending to the most useful information.

- extremely satisfying.

- a time during which they begin to interact with a much wider circle of people.

c.

Question 10.13

| 3. | Which is true of marital satisfaction over the life span? |

- It increases steadily.

- It decreases steadily.

- It is remarkably stable.

- It shows peaks and valleys, corresponding to the presence and ages of children.

d.