1.3 The Search for Objective Measurement: Behaviorism Takes Center Stage

In 1894, a student of Titchener’s, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) published an influential book, The Animal Mind. She reviewed what was then known about perception, learning, and memory in different animal species. She argued that nonhuman animals, much like human animals, have conscious mental experiences (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987). Watson vehemently disagreed.

Archives of the History of American Psychology

The schools of psychological thought that had developed by the early 20th century— structuralism, functionalism, and psychoanalysis—differed substantially from one another. But they shared an important similarity: Each tried to understand the inner workings of the mind by examining what the owners of those minds had to say about them. People reported on their perceptions, thoughts, memories, and feelings, and psychologists used those data to figure out what was going on inside. But some psychologists found these kinds of data to be distressingly imprecise and subjective, and as the 20th century unfolded, these psychologists developed a new approach. Behaviorism was the idea that psychology should restrict itself to studying objectively observable behavior, and it represented a dramatic departure from previous schools of thought.

behaviorism

An approach that advocates that psychologists restrict themselves to the scientific study of objectively observable behavior.

Watson and the Emergence of Behaviorism

John Broadus Watson (1878–1958) believed that private experience could never be a proper object of scientific inquiry. Science required replicable, objective measurements of phenomena that are accessible to all observers, and verbal reports of subjective experience did not pass that test. So instead of asking people to report on their mental lives, Watson proposed that psychologists should instead study behavior—what people do, rather than what people say—because behavior can be measured reliably and objectively.

How did behaviorism help psychology advance as a science?

Watson was deeply interested in the work of Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936), who studied digestion in dogs. In the course of his work, Pavlov had noticed that his dogs not only salivated at the sight of food, but they also salivated at the sight of the person who fed them. The feeders were not dressed in Alpo suits, so why should the mere sight of people trigger a basic digestive response? To answer this question, Pavlov developed a procedure in which he sounded a tone every time he fed the dogs, and then he looked to see what happened when he sounded the tone but didn’t feed them. And what happened was this: They drooled! Pavlov went on to develop a hugely important theory to explain how the sound of a tone could cause a dog to drool (and you’ll learn all about it in Chapter 7). He referred to the tone as the stimulus (which is a sensory input from the environment) and to salivation as the response (which is a reaction to a stimulus). Watson made these ideas the building blocks of behaviorism, which is sometimes called stimulus–response (S–R) psychology.

stimulus

Sensory input from the environment.

response

An action or physiological change elicited by a stimulus.

B. F. Skinner and the Development of Behaviorism

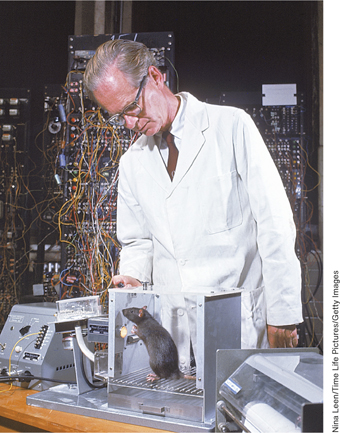

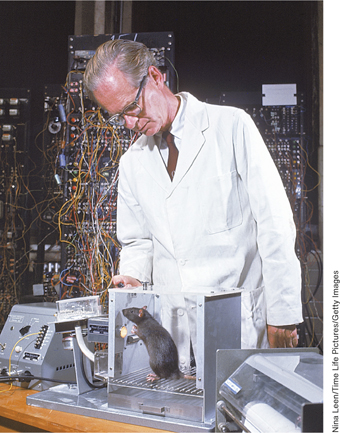

Burrhus Frederick Skinner (1904–1990) admired Pavolv’s experiments and Watson’s theories, but he thought something important was still missing. Pavlov’s dogs had been passive participants that stood around, listened to tones, and drooled. Skinner recognized that in everyday life, animals don’t just stand there—they do something! Animals act on their environments in order to find shelter, food, or mates, and Skinner wondered if he could develop behaviorist principles that would explain how animals learned to do all those things.

Inspired by Watson’s behaviorism, B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) investigated the way an animal learns by interacting with its environment. Here, he demonstrates the Skinner box, in which rats learn to press a lever to receive food.

Nina Leen/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

Skinner built what he called a conditioning chamber but that the rest of the world would forever call a Skinner box. The box had a lever and a food tray, and a hungry rat could get food delivered to the tray simply by pressing the lever. But rats can’t read instruction manuals, so how do they learn to do this? Skinner noticed that when a rat was put in the box, it would wander around for a bit, sniffing, touching, and exploring the box. After a while, the rat would accidentally lean on the bar and then—viola!—a food pellet would appear in the tray. So the rat would lean again—and again be fed. Once that happened a few times, the rat would start pressing the bar like a bongo player, stopping only when it was full. Skinner used this observation to postulate the principle of reinforcement, which states that the consequences of a behavior determine whether it will be more or less likely to occur again.

reinforcement

The consequences of a behavior determine whether it will be more or less likely to occur again.

What did Skinner learn by observing the behavior of hungry rats?

The concept of reinforcement became the foundation for Skinner’s “new behaviorism” (Skinner, 1938), and he used it to solve problems in everyday life. For example, one day he was visiting his daughter’s fourth-grade class when he realized that he could improve classroom learning by breaking complicated tasks into small bits and then using the principle of reinforcement to teach children each bit (Bjork, 1993). To learn a complicated math problem, for instance, students would first be asked an easy question about the simplest part of the problem. They would then be told whether the answer was right or wrong, and if a correct response was made, they would move on to a more difficult question. Skinner thought that the satisfaction of knowing they were correct would be reinforcing and help students learn.

If fourth graders and rats could be successfully trained, then why stop there? In a series of controversial popular books (Skinner, 1986; 1971), Skinner laid out his vision of a utopian society in which behavior was controlled by the judicious application of the principle of reinforcement. Skinner claimed that our subjective sense of free will is an illusion and that when we think we are exercising free will, we are actually responding to present and past patterns of reinforcement. We do things in the present that have been rewarding in the past, and our sense of “choosing” to do them is nothing more than an illusion. Not surprisingly, these claims sparked an outcry from critics who believed that Skinner was calling for a repressive society that manipulated people for its own ends. According to the great intellectual magazine, TV Guide, Skinner was advocating “the taming of mankind through a system of dog obedience schools for all” (Bjork, 1993, p. 201). In fact, Skinner was merely suggesting that knowledge of the principles that govern human behavior could be used to increase human well-being. In any case, the controversy certainly increased Skinner’s well-being: A popular magazine that listed the 100 most important people who ever lived ranked him just 39 points below Jesus Christ (Herrnstein, 1977).

Which of Skinner’s claims provoked an outcry?

Skinner’s well-publicized questioning of such cherished notions as free will led to a rumor that he had raised his own daughter in a Skinner box. This urban legend, while untrue, likely originated from the climate-controlled, glass-encased crib that he invented to protect his daughter from the cold Minnesota winter. Skinner marketed the crib under various names, including the “Air-crib” and the “Heir Conditioner,” but it failed to catch on with parents.

Bettmann/Corbis

SUMMARY QUIZ [1.3]

Question

1.11

| 1. |

Behaviorism involves the study of |

- observable actions and responses.

- the potential for human growth.

- unconscious influences and childhood experiences.

- human behavior and memory.

a.

Question

1.12

| 2. |

The experiments of Ivan Pavlov and John Watson centered on |

- perception and behavior.

- stimulus and response.

- reward and punishment.

- conscious and unconscious behavior.

b.

Question

1.13

| 3. |

Who developed the concept of reinforcement? |

- B. F. Skinner

- Ivan Pavlov

- John Watson

- Margaret Floy Washburn

a.