9.6 Who Is Most Intelligent?

If everyone in the world were equally intelligent, we probably wouldn’t even have a word for it. What makes intelligence such an interesting and important topic is that some individuals—

Individual Differences in Intelligence

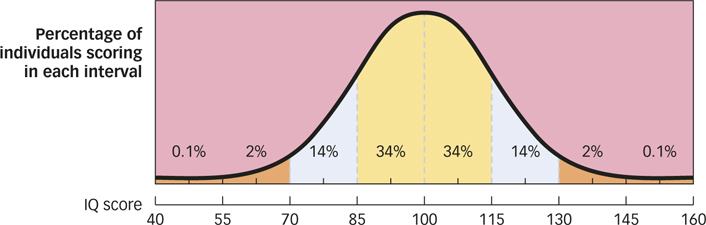

The average IQ is 100, and the vast majority of us—

Those of us who occupy the large middle of the intelligence spectrum often embrace a number of myths about those who live at the extremes. For example, movies typically portray the “tortured genius” as a person (usually a male person) who is brilliant, creative, misunderstood, despondent, and more than a little weird. But for the most part, Hollywood has the relationship between intelligence and mental illness backwards: People with very high intelligence are less prone to mental illness than are people with very low intelligence (Dekker & Koot, 2003; Didden et al., 2012; Walker et al., 2002) and very high IQ children are about as well-

306

What one thing clearly distinguishes gifted children?

On the other end of the intelligence spectrum are people with intellectual disabilities, which is defined by an IQ of less than 70. About 70% of people with IQs in this range are male. Two of the most common causes of intellectual disability are Down syndrome (caused by the presence of a third copy of chromosome 21) and fetal alcohol syndrome (caused by a mother’s alcohol use during pregnancy). Unlike intellectual gifts, intellectual disabilities tend to be quite general, and people who have them typically show impaired performance on most or all cognitive tasks. Perhaps the greatest myth about the intellectually disabled is that they are unhappy. A recent survey of people with Down syndrome (Skotko, Levine, & Goldstein, 2011) revealed that more than 96% are happy with their lives, like who they are, and like how they look. People with intellectual disabilities face many challenges, and being mistaken for miserable people is clearly one of them.

Group Differences in Intelligence

In the early 1900s, Stanford professor Lewis Terman improved on Binet and Simon’s work and produced the intelligence test now known as the Stanford–

Was Terman right or wrong? Terman made three claims: First, he claimed that intelligence is influenced by genes; second, he claimed that members of some racial groups score better than others on intelligence tests; and third, he claimed that the difference in scores is due to a difference in genes. Virtually all modern scientists agree that Terman’s first two claims are indeed true: Intelligence is influenced by genes and some groups do perform better than others on intelligence tests. However, Terman’s third claim—

Before answering that question, we should be clear about one thing: Between-

But fair or not, they do. Whites routinely outscore Latinos, who routinely outscore Blacks (Neisser et al., 1996; Rushton, 1995). Women routinely outscore men on tests that require rapid access to and use of semantic information, production and comprehension of complex prose, fine motor skills, and perceptual speed of verbal intelligence, and men routinely outscore women on tests that require transformations in visual or spatial memory, certain motor skills, spatiotemporal responding, and fluid reasoning in abstract mathematical and scientific domains (Halpern, 1997; Halpern et al., 2007). Indeed, group differences in performance on intelligence tests “are among the most thoroughly documented findings in psychology” (Suzuki & Valencia, 1997, p. 1104). Although the average difference between groups is considerably less than the average difference within groups, Terman was right when he noted that some groups perform better than others on intelligence tests. The question is why?

307

Tests and Test Takers

One possibility is that there is something wrong with the tests. In fact, the earliest intelligence tests asked questions whose answers were more likely to be known by members of one group (usually White Europeans) than by members of another. For example, when Binet and Simon asked students, “When anyone has offended you and asks you to excuse him, what ought you to do?,” they were looking for answers such as “accept the apology graciously.” Answers such as “demand three goats” would have been counted as wrong. But intelligence tests have come a long way in a century, and one would have to look hard to find questions on a modern intelligence test that have the same blatant cultural bias that Binet and Simon’s test did (Suzuki & Valencia, 1997). It would be difficult to argue that the large differences between the average scores of different groups is due entirely—

How can the testing situation affect a person’s performance on an IQ test?

And yet, even when test questions are unbiased, testing situations may not be. For example, studies show that African American students perform more poorly on tests if they are asked to report their race at the top of the answer sheet, because doing so causes them to feel anxious about confirming racial stereotypes (Steele & Aronson, 1995) and anxiety naturally interferes with test performance (Reeve, Heggestad, & Lievens, 2009). European American students do not show the same effect when asked to report their race. When Asian American women are reminded of their gender, they perform unusually poorly on tests of mathematical skill, presumably because they are aware of stereotypes suggesting that women can’t do math. But when the same women are instead reminded of their ethnicity, they perform unusually well on such tests, presumably because they are aware of stereotypes suggesting that Asians are especially good at math (Shih, Pittinsky, & Ambady, 1999). Findings such as these remind us that the situation in which intelligence tests are administered may cause group differences in performance that do not reflect group differences in actual intelligence.

Environments and Genes

Biases in the testing situation may explain some of the between-

How can environmental factors help explain between-

Do genes play any role in this difference? So far, there is no compelling evidence that they do. For example, the average African American has about 20% European genes, and yet those who have more are no smarter than those who have fewer, which is not what we’d expect if European genes made people smart (Loehlin, 1973; Scarr et al., 1977). Similarly, African American children and mixed-

308

Improving Intelligence

Intelligence can be improved—

How might children’s intelligence be enhanced?

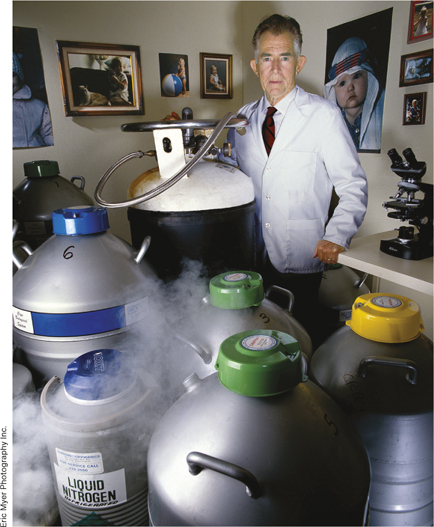

Perhaps all this will be simpler in the future. Cognitive enhancers are drugs that produce improvements in the psychological processes that underlie intelligent behavior. For example, stimulants such as Ritalin (methylphenidate) and Adderall (mixed amphetamine salts) can enhance cognitive performance by improving people’s ability to focus attention, manipulate information in working memory, and flexibly control responses (Sahakian & Morein-

Some scientists believe that cognitive enhancement will eventually be achieved by altering the brain’s basic structure at birth. By manipulating the genes that guide hippocampal development, scientists have created a strain of “smart mice” that have extraordinary memory and learning abilities, leading the researchers to conclude that “genetic enhancement of mental and cognitive attributes such as intelligence and memory in mammals is feasible” (Tang et al., 1999, p. 64). Although no one has yet developed a safe and powerful “smart pill” or “smart gene therapy,” many experts believe that this will happen in the next few years (Farah et al., 2004; Rose, 2002; Turner & Sahakian, 2006). When it does, we will need a whole lot of intelligence to know how to handle it.

309

SUMMARY QUIZ [9.6]

Question 9.19

| 1. | Which of the following statements is false? |

- Modern intelligence tests have a very strong cultural bias.

- Testing situations can impair the performance of some groups more than others.

- Test performance can suffer if the test taker is concerned about confirming a racial or gender stereotype.

- Some ethnic groups perform better than others on intelligence tests.

a.

Question 9.20

| 2. | On which of the following does broad agreement exist among scientists? |

- Differences in the intelligence test scores of different ethnic groups are clearly due to genetic differences between those groups.

- Differences in the intelligence test scores of different ethnic groups are caused in part by factors such as low birth weight and poor diet that are more prevalent in some groups than in others.

- Differences in the intelligence test scores of different ethnic groups always reflect real differences in intelligence.

- Genes that are strongly associated with intelligence have been found to be more prevalent in some ethnic groups than in others.

b.

Question 9.21

| 3. | Gifted children tend to |

- be equally gifted in several domains.

- be gifted in a single domain.

- lose their special talent in adulthood.

- change the focus of their interests relatively quickly.

b.