Science and Psychology

FRUSTRATED MINERS

Extreme circumstances tend to awaken the darker elements of human nature, and the Chilean mining ordeal was no exception. During those first 17 days underground, the men split into three factions, each with its own designated leader and sleeping territory. They squabbled over pieces of cardboard that they used as mattresses, and a few arguments reportedly escalated into fistfights (CBS News/Associated Press, 2010, October 16; Franklin, 2011). But the same life-or-death situations that elicit what is most ugly about humankind can also summon what is most beautiful—our ability to feel compassion, to comfort and support one another, and to sacrifice personal needs for the benefit of the group. In the case of Los 33, the beautiful triumphed over the ugly.

Extreme circumstances tend to awaken the darker elements of human nature, and the Chilean mining ordeal was no exception. During those first 17 days underground, the men split into three factions, each with its own designated leader and sleeping territory. They squabbled over pieces of cardboard that they used as mattresses, and a few arguments reportedly escalated into fistfights (CBS News/Associated Press, 2010, October 16; Franklin, 2011). But the same life-or-death situations that elicit what is most ugly about humankind can also summon what is most beautiful—our ability to feel compassion, to comfort and support one another, and to sacrifice personal needs for the benefit of the group. In the case of Los 33, the beautiful triumphed over the ugly.

The men were able to move beyond their personal disputes and see the big picture. They realized that banding together was the only sensible way to endure. Like players on a team, they began to assume special roles and responsibilities. The “pastor” José Henríquez led the group in regular prayers; the “electrician” Edison Peña cobbled together a bootleg lighting system; and the “doctor” Yonny Barrios drew from the knowledge of medicine he learned while caring for his sick mother. The miners selected two very different yet complementary leaders: the foreman Luis Urzúa and a second unofficial leader named Mario Sepúlveda. Formerly known as “El Loco” or the “Crazy One,” Sepúlveda once pole-danced on the bus the miners daily rode, sending them into fits of laughter. Now they looked to him for strength and inspiration (Franklin, 2011).

To break the monotony of their subterranean existence, the miners coordinated their daily activities, starting their morning with a prayer, holding a midday “townhall” meeting where they voted democratically on all major decisions, and praying again in the afternoon. When it was time for their daily meal, they gathered like a family, politely waiting to eat until all 33 members had been served (Franklin, 2011).

The men experienced their share of psychological meltdowns during those first 17 days, but they found comfort in the bonds of brotherhood. “We were like a family,” said Samuel Ávalos. “When someone falls, you pick them up” (Franklin, 2011, p. 103). And like very close family members, they could almost feel each other’s pain. “I was more worried about my companions,” said Ávalos, referring to the younger men who had just started to raise families. “They had little babies, pregnant wives. That broke me…. To see my compañeros cry and cry” (p. 109).

17

The roles these men assumed, the ways in which they cooperated, and the emotional support they offered to each other are just the types of social dynamics that social scientists would be interested in studying (Chapter 15). Equally interesting from the standpoint of social psychology was the manner in which people throughout the world responded when they learned that rescuers had made contact with the miners.

THINK again

What’s in a Number?

When news broke that Los 33 were alive and well, Chile erupted in celebration (Reuters, 2010, August 22). News of the trapped miners was headlined, broadcast, and tweeted across the globe. It was difficult to believe that all 33 men had survived the rockfall and endured 17 days in a sweltering hole with no food or clean water—and done so with honor and dignity. Some said it was testament to the goodness of the human spirit. Others called it a miracle of God. Still others pointed to the mystical nature of numerology, which attempts to provide explanations for a variety of events and observations. The number 33, which numerologists consider a “master healer” (Culbertson, 2009, October 15), was thought to play an important role in the rescue of the Chilean miners. Here is some of the “evidence” presented to support this claim (AFP, 2010, October 13; freedomflores, 2010, October 18; The Vigilant Citizen, 2010, October 14):

When news broke that Los 33 were alive and well, Chile erupted in celebration (Reuters, 2010, August 22). News of the trapped miners was headlined, broadcast, and tweeted across the globe. It was difficult to believe that all 33 men had survived the rockfall and endured 17 days in a sweltering hole with no food or clean water—and done so with honor and dignity. Some said it was testament to the goodness of the human spirit. Others called it a miracle of God. Still others pointed to the mystical nature of numerology, which attempts to provide explanations for a variety of events and observations. The number 33, which numerologists consider a “master healer” (Culbertson, 2009, October 15), was thought to play an important role in the rescue of the Chilean miners. Here is some of the “evidence” presented to support this claim (AFP, 2010, October 13; freedomflores, 2010, October 18; The Vigilant Citizen, 2010, October 14):

- There were 33 miners.

- They sent up a note saying, “Estamos bien en el refugio los 33.” This statement contains 33 characters and spaces.

- The eventual rescue date was 10/13/10; the sum of these digits equals 33.

- Drilling the rescue tunnel took 33 days, and the width of the rescue tunnel was said to be 66 centimeters, which is 33 times two.

NUMEROLOGY TO THE RESCUE?

Are you detecting a pattern? Anyone can draw a connection or find a pattern if they try hard enough, and these patterns do not necessarily represent a unifying theory or provide a scientific explanation. They are just coincidences.

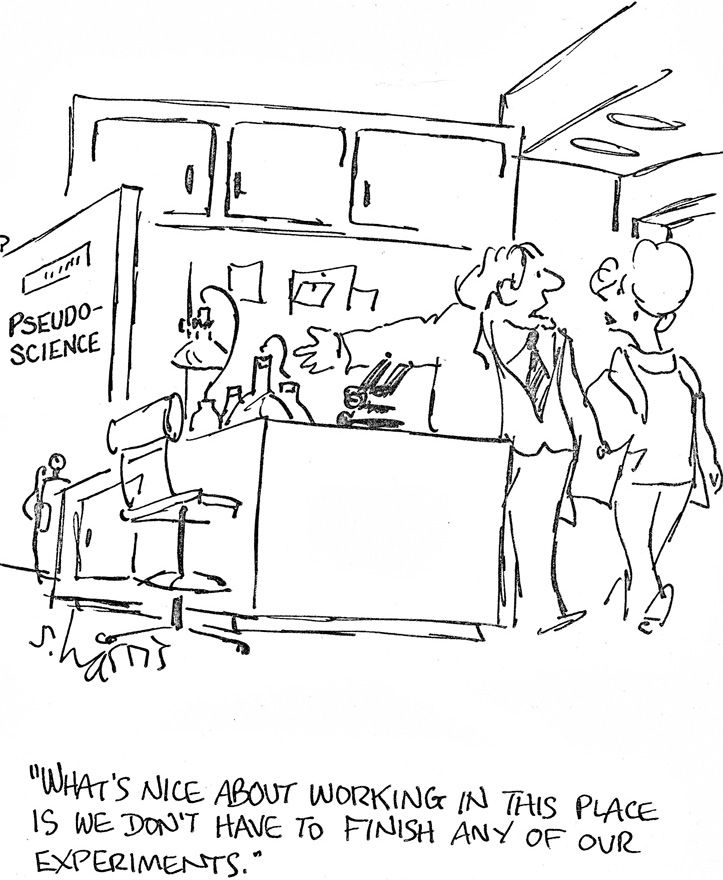

While the beliefs surrounding numerology may have provided a meaningful way for some people to interpret the miners’ experiences, such beliefs have no scientific validity. In the following section, we’ll examine “pseudosciences” like numerology and explain how we use critical thinking to evaluate them in comparison to scientific research and thought.

LO 6 Evaluate pseudopsychology and its relationship to critical thinking.

As intriguing as this apparent 33 theme may be, it has no scientific meaning. Numerology is a prime example of pseudopsychology, an approach to explaining and predicting behavior and events that appears to be psychology but is not supported by empirical, objective evidence. Another familiar pseudopsychology is astrology, which uses a chart of the heavens called a horoscope to predict everything from the weather to romantic relationships. Surprisingly, many people have difficulty distinguishing between pseudosciences, like astrology, and true sciences. One study found that nearly half of college science majors could not tell the difference between astrology, the pseudoscience, and astronomy, the actual scientific study of stars and other celestial bodies (De Robertis & Delaney, 1993).

18

Why do horoscopes often seem to be accurate in their descriptions and predictions? Consider this excerpt from a monthly Cancer horoscope: “Life at home or time spent dealing with your family will require more patience and cooperation than usual. Others might need advice or help and you may have to make yourself available” (Horoscope. com, 2012). When you think about it, this statement could apply to just about any human being on the planet. Doesn’t dealing with family inevitably require extra “patience and cooperation”? And isn’t it true that family and friends often ask for help and advice? How could you possibly prove such a statement wrong? You couldn’t. That’s why astrology is not science. A telltale feature of a pseudopsychology, like any pseudoscience, is its tendency to make assertions so broad and vague that they cannot be refuted (Stanovich, 2010).

Critical Thinking

Why can’t we use pseudopsychology to help predict and explain behaviors? Because there is no solid evidence for its effectiveness, no scientific support for its findings. Critical thinking is absent from the “pseudotheories” used to explain the pseudopsychologies (Rasmussen, 2007). What is critical thinking and when should we use it? Critical thinking is the process of weighing various pieces of evidence, synthesizing them (putting them together), and determining how each contributes to the bigger picture. Critical thinking requires one to consider the source of information and the quality of evidence before making a decision on the validity of material. The process involves thinking beyond definitions, focusing on underlying concepts and applications, and being open-minded and skeptical at the same time. Psychology is driven by critical thinking; pseudopsychology is not (Rasmussen, 2007).

Let’s put our critical thinking skills to work by examining the numerological “evidence” pertaining to Los 33. First, can we trust the data? One source suggests the rescue hole was 66 centimeters, but another says it was 68 centimeters. Some miners were rescued on 10/13/10, but others emerged on 10/14/10 (the rescue took place over the course of 2 days). Hmm, some of the 33s appear to be fading into thin air. Lesson learned: We should use critical thinking to evaluate the evidence for a claim.

But critical thinking goes far beyond verifying the facts (Yanchar, Slife, & Warne, 2008). Even if every piece of numerological evidence was spot-on, you would still have to weigh the relative importance of each piece of information and combine them all in a logical way: What do all these 33s mean, and can your conclusion predict what happens next? Here, we run into trouble again. Numerology and other pseudosciences cannot effectively predict future events.

Critical thinking is an invaluable skill, whether you are a trapped miner struggling to survive, a psychologist planning an experiment, or a student trying to earn a good grade in psychology class. For example, has anyone ever told you that choosing “C” on a multiple-choice question is your best bet when you don’t know the answer? There is little research showing this is the best strategy (Skinner, 2009). Next time you’re offered a tempting niblet of folk wisdom, think before you bite: What kind of evidence exists to support this claim? Can it be used to predict future events?

Using the principles of critical thinking, see what you can gather from the findings related to handwriting analysis and dishonesty presented in From the Pages of Scientific American.

19

from the pages of SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

Murder, She Wrote

Handwriting Analysis May Reveal Dishonesty

A new study adds “writing with large strokes and applying high pressure on paper” to the list of telltale signs that someone might be lying. Researchers at Haifa University in Israel could tell whether or not students were writing the truth by analyzing these physical properties of their handwriting.

Lying requires more cognitive resources than being truthful, says lead author Gil Luria. “You need to invent a story, make sure not to contradict yourself, etcetera.” Any task done simultaneously, therefore, becomes less automatic. Tabletop pressure sensors showed this effect in the students’ handwriting, which became more belabored when they fibbed.

Handwriting analysis could eventually complement other lie detection methods and would add a new dimension because, unlike almost all other techniques, it doesn’t rely on verbal communication, Luria says.

Nicole Branan. Reproduced with permission. Copyright © 2010 Scientific American, a division of Nature America, Inc. All rights reserved.

show what you know

Question 1.1

1. An instructor in the psychology department assigns a project requiring students to read several journal articles on a controversial topic. They are then required to weigh various pieces of evidence from the articles, synthesize the information, and determine how the various findings contribute to understanding the topic. This process is known as:

- pseudotheory.

- critical thinking.

- hindsight bias.

- applied research.

Question 1.2

2. __________ is an approach to explaining and predicting events that appears to be psychology but is not supported by empirical, objective evidence.

Question 1.3

3. How would you explain to someone that astrology is a pseudopsychology?

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.