10.1 Sex and Sexuality

sexuality and gender

GUESS THE PROFESSION

Sex and Sexuality

GUESS THE PROFESSION

Stephen Patten usually walks into Portland’s veteran’s hospital around 6:00 a.m. Then he checks his e-mail, puts on his scrubs, and heads to the operating room to prepare for the day’s surgeries. What do you think Stephen does for a living?

Stephanie Buehler spends much of her workday discussing erections, orgasms, and relationship woes. People of all different ages, ethnicities, and cultural backgrounds come to her for help with their most intimate problems. What is Stephanie’s profession?

Stephen Patten is a nurse. But if you guessed he is a doctor, you’re not alone. Many of Stephen’s patients jump to the same conclusion when they see a man in his mid-fifties approach their bedside. Stephen is indeed unusual in his field: More than 90% of nurses in the United States are women, according to a 2008 survey (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2010). But there is another reason patients do a double take when this 200-pound lumberjack type walks through the door and says, “Hi, I’m Stephen. I’ll be your nurse today.” It has to do with our notions of masculine and feminine. In other words, it relates directly to gender, a concept we will explore in the upcoming pages.

Dr. Stephanie Buehler is a certified sex therapist, a psychotherapist who specializes in helping individuals and couples resolve sexual issues. You may think your secret sexual fantasies are unusual, but Dr. Buehler would probably not be surprised if you shared them with her. It takes a lot to shock a woman who spends 8 hours a day discussing sexual concerns with all types of people. Her clients range in age from 18 to 80 and come from all walks of life. She sees firefighters, physicians, homemakers, and college students like you; she sees heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual clients. Her work has afforded her a privileged view of human sexuality—a slice of which we are going to share with you.

426

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

after reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

- LO 1 Define sex and distinguish it from sexuality.

- LO 2 Identify the biological factors that determine sex.

- LO 3 Identify some of the causes of intersexual development.

- LO 4 Define gender and explain how culture plays a role in its development.

- LO 5 Distinguish between transgender and transsexual.

- LO 6 Describe the human sexual response as identified by Masters and Johnson.

- LO 7 Define sexual orientation and summarize how it develops.

- LO 8 Identify the symptoms of sexual dysfunctions.

- LO 9 Classify sexually transmitted infections and identify their causes.

- LO 10 Describe human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its role in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

- LO 11 Define sexual scripts and describe some of the ways people deviate from sex-related cultural norms.

Let’s Talk About Sex

LO 1 Define sex and distinguish it from sexuality.

When people talk about sex, they often are referring to a sexual act such as intercourse. But sex can also refer to the classification of people as male or female, a distinction based on genetic composition and the structure and/or function of reproductive organs (Pryzgoda & Chrisler, 2000). Gender, on the other hand, refers to the dimension of masculinity and femininity based on social, cultural, and psychological characteristics. The American Psychological Association (APA, 2010c, 2011a) recommends using the term “sex” when referring to biological status and “gender” for the cultural roles and expectations that distinguish males and females. According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013), “gender” also indicates the public and often legally recognized role a person has as a man or woman, boy or girl.

From your reading of other chapters in this book, you know that psychologists often view behaviors as resulting from an interaction of biological, psychological, and social forces. We will use this biopsychosocial perspective to emphasize the role these factors play in our sexuality. In other words, how they influence our sexual activities, attitudes, and behaviors.

Sex: It’s In Your Biology

What are the topics of sex and gender doing in a psychology textbook, and are they important enough to merit their own chapter? Sex and gender play a role in the scientific study of behavior and mental processes, serving as important variables to be studied. And you know intuitively that relationships and emotions related to sexuality are a part of what makes us human.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we describe variables as measurable characteristics that can vary or change over time. Some variables, like sex and gender, vary across groups, and we study their impact on the members of those groups. In this chapter, we will explore sex and gender as they relate to a variety of topics in psychology.

Note: Quotations attributed to Stephen Patten and Dr. Stephanie Buehler are personal communications.

427

In this chapter, you will learn about the biology of sexual determination and differences of sex development, and explore how sex influences human behavior. Sex is one of the most intimate—and fascinating—dimensions of human behavior. It is also one of the most difficult to study.

A very personal topic for most people, sex is not openly discussed in many homes, schools, doctors’ offices, or even bedrooms in North America (Byers, 2011). This is ironic, given that North American culture supplies a steady stream of sexual imagery, words, and media. Many parents feel embarrassed discussing sex with their children. Medical and mental health professionals find it difficult to communicate with patients about sexual issues. Some of us cannot even talk honestly about sex with our sexual partners.

Dr. Buehler, in her own words:

Research and Sex

Researchers use a variety of approaches to study human sexuality, including surveys, interviews, case studies, and the experimental method. There are also many technologies to observe and measure physiological responses (Chivers, Seto, Lalumiere, Laan, & Grimbos, 2010). For example, MRI and fMRI can be used to study sexual arousal during intercourse and other sexual activities (Schultz, van Andel, Sabelis, & Mooyaart, 1999).

But as you can imagine, studying sexual behavior has its difficulties. People are often uncomfortable discussing sex, especially their own sex lives, so getting participants to open up can be tricky. The extreme intimacy many people feel about their sexuality can also make research that includes the observation of sexual behavior especially challenging. As a result, our knowledge of sexual behavior is often limited to self-reporting. Yet there are problems with relying on self-reported data, including the tendency for some people to be dishonest or portray themselves in the best possible light. There are ways to sidestep these issues, however. For example, Rieger and Savin-Williams (2012) had participants view short video clips of images that were neutral (landscape) or sexually explicit (male or female models masturbating). Given that our pupils dilate when we are sexually aroused, the researchers were able to use this variable as an index of sexual arousal. They measured the degree to which participants’ pupils dilated when they looked at neutral versus sexually explicit images, gauging the participants’ sexual arousal without being too intrusive.

428

Not everyone is shy about personal sexual behavior, of course, and that is good news for researchers. Participants in human sexuality studies engage in a variety of sexual activities, including sexual intercourse and masturbation, with approval from Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to ensure ethical treatment.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the importance of using representative samples. Here, we refer to participants who have chosen to take part in human sexuality research. We must interpret findings cautiously as their behaviors may not reflect those of the general population.

Now it’s time to delve into the heart of the chapter. Get ready to explore the many facets of sexuality and gender.

The Biology of Sexual Determination

A person’s sex (male or female) depends on both genes and hormones. Sex determination refers to the designation of genetic sex, which guides the activity of hormones that direct the development of reproductive organs and structures (Ngun, Ghahramani, Sánchez, Bocklandt, & Vilain, 2011). Let’s take a closer look at how all this works.

LO 2 Identify the biological factors that determine sex.

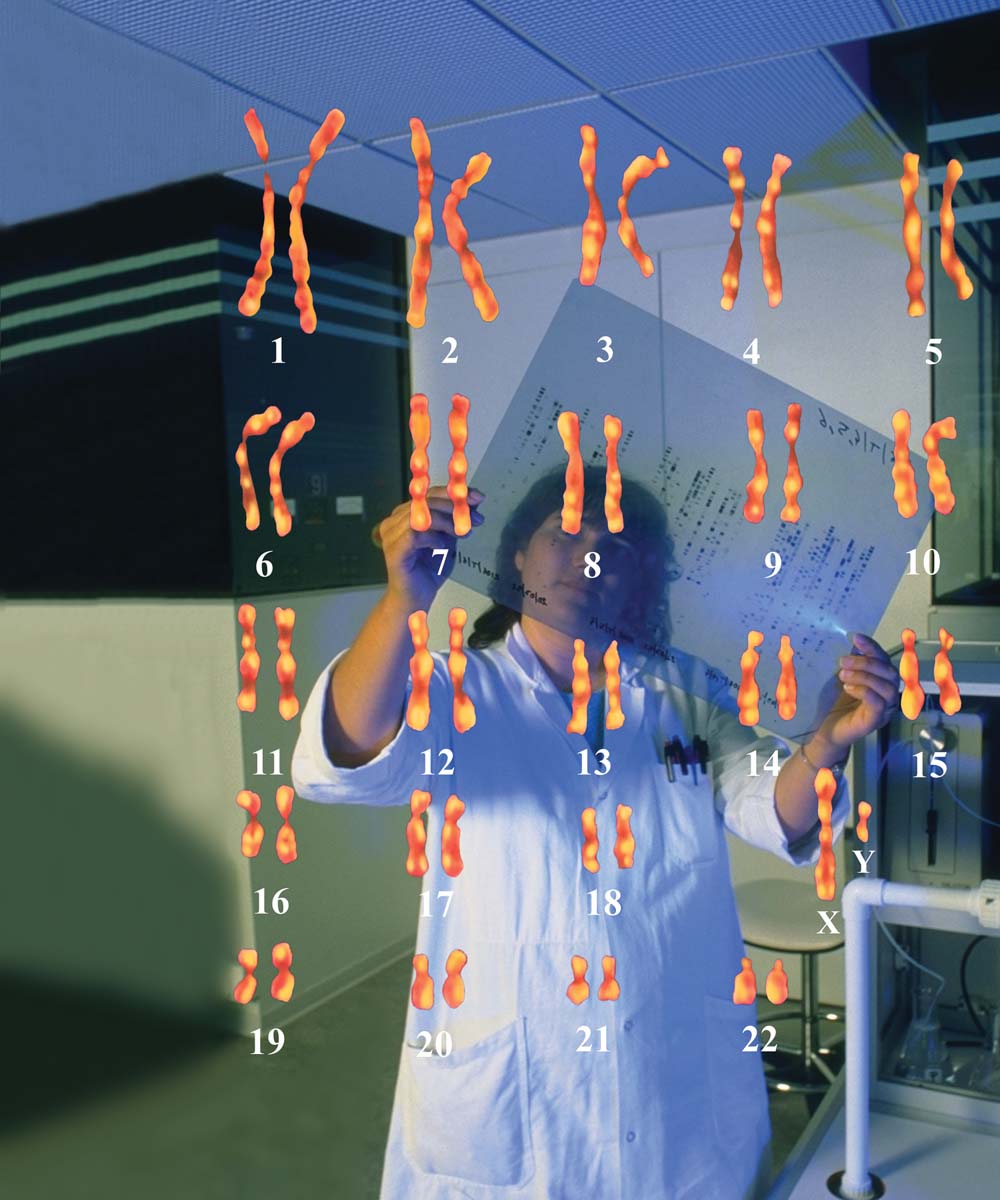

Your genetic sex was determined by your father’s sperm. In the moment of conception, dad’s sperm united with mom’s egg to form a zygote. A zygote contains genetic material from both parents in the form of 46 chromosomes—23 from mom, 23 from dad. These chromosomes provide the blueprint for biological development, including that of the physiological structures associated with sex. The 23rd pair of chromosomes, also referred to as the sex chromosomes, includes specific instructions for the zygote to develop into a female or a male. It’s as simple as X and Y.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 8, we learned that the mother’s ovum and the father’s sperm come together and form a single cell known as a zygote. Under normal circumstances, the zygote continues to divide as it moves through the fallopian tube toward the uterus. The resulting mass of cells eventually implants in the uterine wall.

Sex Chromosomes

The egg from the mother carries an X chromosome, and the sperm from the father carries either an X chromosome or a Y chromosome. When the sperm contributes an X chromosome to the 23rd pair, the genetic sex is XX, and the zygote generally develops into a female. If the sperm carries a Y chromosome, the genetic sex is XY, and the zygote typically develops into a male. About 50% of sperm carry the X chromosome, and 50% carry the Y chromosome. This is the reason the population is approximately half male and half female.

Genes and Hormones

From the moment a zygote is formed, genetic sex is constant. In other words, the composition of the 23rd pair of chromosomes remains female (XX) or male (XY). We should note, however, that the structure and function of the reproductive organs do not always match the original genetic sex (XX or XY). The development of reproductive anatomy is influenced by a variety of factors, including interactions among genes and the activity of hormones produced by the sex glands (also known as gonads) of the fetus (Blecher & Erickson, 2007; Dennis, 2004). For the sake of the discussion here, we’ll assume that the genetic sex matches the developing physical characteristics.

429

In a genetic male, the presence of the Y chromosome causes the gonads to become testes. If the Y chromosome is not present, as in the case of a genetic female, then the gonads develop into ovaries (Hines, 2011a). Both the testes and ovaries secrete hormones that influence the development of reproductive organs: androgens in the case of the testes and estrogen in the case of the ovaries. (These sex hormones are also secreted by the adrenal glands in both males and females.) Testosterone, for example, is an androgen that influences whether the fetus develops male or female genitals.

Distinguishing Between Males and Females

Even though the genetic sex of the fetus is determined at conception, it is not possible to ascertain the sex until 7 weeks after conception through blood tests (Devaney, Palomaki, Scott, & Bianchi, 2011). Fetal genital anatomy can be determined by ultrasound by the end of the first trimester (Scheffer et al., 2010). But it is usually not until adolescence that the sex structures kick into reproductive action. Puberty begins, and the cycle of life is poised to continue.

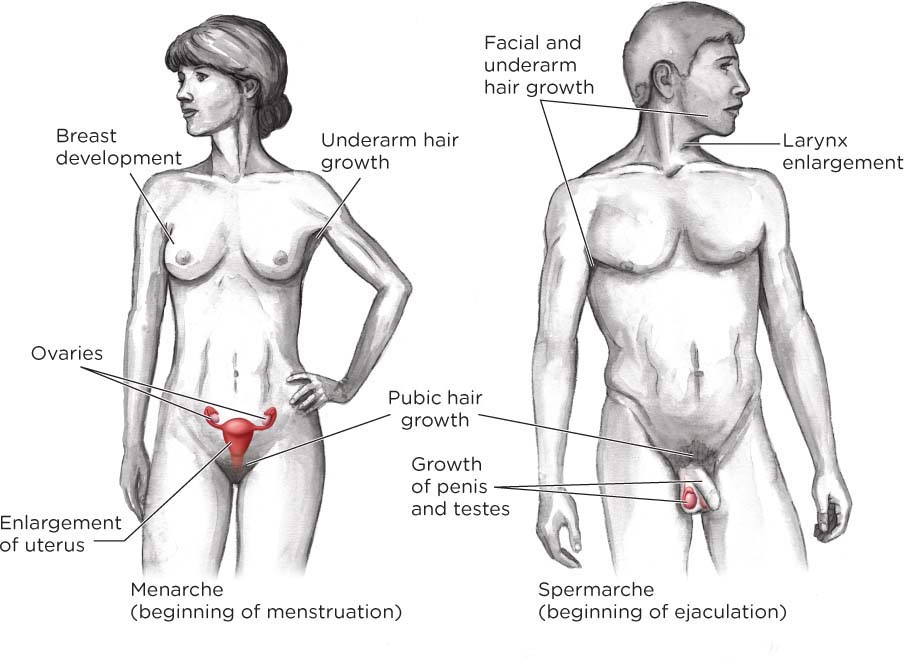

Puberty is a period when notable changes occur in physical development, ultimately leading to sexual maturity and the ability to reproduce. During this time, the primary and secondary sex characteristics develop (Figure 10.1). In addition, one of the most significant changes for males is spermarche, or first ejaculation (often occurring during sleep). The equivalent for females is menarche, or first menstruation (Ladouceur, 2012; Mendle, Harden, Brooks-Gunn, & Graber, 2010).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 8, we noted that primary sex characteristics, including the ovaries, uterus, vagina, penis, scrotum, and testes, are related to reproduction. Secondary sex characteristics, such as deepening of the voice in males and breast development in females, are indirectly involved with reproduction.

Vive la Différence

Apart from the obvious physical differences between the sexes, what else distinguishes males and females? Adult male brains, on average, are approximately 10% larger than adult female brains (Feis, Brodersen, von Cramon, Luders, & Tittgemeyer, 2013). There are also structural disparities in the brain; for example, the cerebral hemispheres are not completely symmetric, and males and females differ somewhat in these asymmetries (Tian, Wang, Yan, & He, 2011). MRI analyses point to sex differences in the brain networks involved in social cognition and visual-spatial abilities (Feis et al., 2013). Some distinctions between male and female brains are believed to be influenced by hormones secreted prenatally, suggesting they have a biological basis (Sanders, Sjodin, & de Chastelaine, 2002).

430

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 9, we described one robust gender difference relating to social cognition: Women are better and faster than men in identifying emotional expressions. However, it is not clear if these differences result from biological or cultural influences.

Cognition

Despite these contrasts in brain size and structure, males and females do not differ significantly in terms of general intelligence (Burgaleta et al., 2012; Halpern et al., 2007), a pairing many researchers find remarkable: “Apparently, males and females can achieve similar levels of overall intellectual performance by using differently structured brains in different ways” (Deary, Penke, & Johnson, 2010, p. 209). Researchers do find different patterns of neurological activity in males and females, but remember that brains can change in response to experience, a phenomenon called neuroplasticity. Sex differences may be due to changes in synaptic connections and neural networks that result from the different experiences of being male or female (Hyde, 2007).

What are some of the functional differences between male and female brains? One important area of difference is mental rotation; studies suggest that men are better than women at mentally rotating objects (Collins & Kimura, 1997). With practice, women may be able to catch up, however. In one study, women who practiced mentally rotating objects while playing computer games showed greater improvement on measures of mental rotation than did the men (Cherney, 2008). Another area of difference is verbal competence. In childhood, girls tend to perform better on tests of verbal ability, but the discrepancies are so small that they don’t provide useful information for making educational decisions (Hyde & Linn, 1988; Wallentin, 2009). Differences in cognitive development between boys and girls are “minimal,” and these disparities are only responsible for a small proportion of the variability in children’s scores on cognitive tasks (Ardila, Rosselli, Matute, & Inozemtseva, 2011).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we explored mental imagery, which is involved in the cognitive task of mental rotation. Here, we see that this visual-spatial ability seems to be different for men and women, although it is not clear how much is due to biology and how much is due to environmental influences.

Research suggests that some cognitive gender disparities carry over into adulthood, with women outperforming men in verbal tasks and men showing greater spatial and mathematical abilities. These differences between men and women have declined over the past several decades, suggesting changes in sociocultural factors, such as greater availability of advanced math courses and more support for both men and women to pursue careers that interest them (Deary et al., 2010; Wai, Cacchio, Putallaz, & Makel, 2010). When it comes to mathematics performance in children, gender is not the best predictor; environmental factors such as mother’s education, the learning environment of the home, and effectiveness of the elementary school are “far stronger predictors” (Lindberg, Hyde, Petersen, & Linn, 2010).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we learned there are many similarities between male and female brains, but some disparities do exist. The differences in brain function, although biological, can also be explained in terms of experience.

Aggression

We’ve discussed gender disparities in brain anatomy and cognitive abilities, but how do males and females differ in terms of behavior? Men tend to demonstrate more physical aggression (such as hitting) than females (Ainsworth & Maner, 2012; see Chapter 15), but that doesn’t mean females aren’t aggressive in their own way. Some researchers report that females exhibit more relational aggression, or aggressive behaviors that are indirect and aimed at relationships, such as spreading rumors or excluding certain group members (Archer, 2004; Archer & Coyne, 2005; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). These gender differences typically appear early in life (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008; Hanish, Sallquist, DiDonato, Fabes, & Martin, 2012).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7 and Chapter 8 we presented the concept of heritability (in relation to intelligence and schizophrenia, for example). Here, we note that around half of the variability in aggressive behavior can be attributed to genes and the other half to environment.

What causes these differences in males and females? One hormonal candidate is testosterone, which has been associated with aggression (Montoya, Terburg, Bos, & van Honk, 2012) and, as discussed earlier, exists at higher levels in males. Studies of identical twins suggest that approximately 50% of aggressive behavior can be explained by genetic factors (DiLalla, 2002; Tackett, Waldman, & Lahey, 2009). This implies that a significant proportion of gender differences in aggressive behavior results from an interaction between environmental factors and genetics (Brendgen et al., 2005; Rowe, Maughan, Worthman, Costello, & Angold, 2004). In addition, researchers have noted that boys tend to be more aggressive when raised in nonindustrial societies; patriarchal societies, in which women have less power and are considered inferior to men; and polygamous societies, in which men can have more than one wife. Why are these males more aggressive? Evolutionary psychology would suggest that competition for resources (including females) increases the likelihood of aggression (Wood & Eagly, 2002).

431

One thing to keep in mind is that, overall, the variation within a gender is much greater than the variation between genders: “Males and females are similar on most, but not all, psychological variables” (Hyde, 2007, p. 260). This gender similarities hypothesis proposed by Hyde (2005) states that males and females exhibit large differences in only a few areas, including some motor behaviors (throwing distance), some characteristics of sexuality (frequency of masturbation), and to a moderate degree, aggression. These physical and behavioral differences between males and females are interesting, but keep in mind that sex development does not always occur along a strictly “male” or “female” path.

Differences of Sexual Development

LO 3 Identify some of the causes of intersexual development

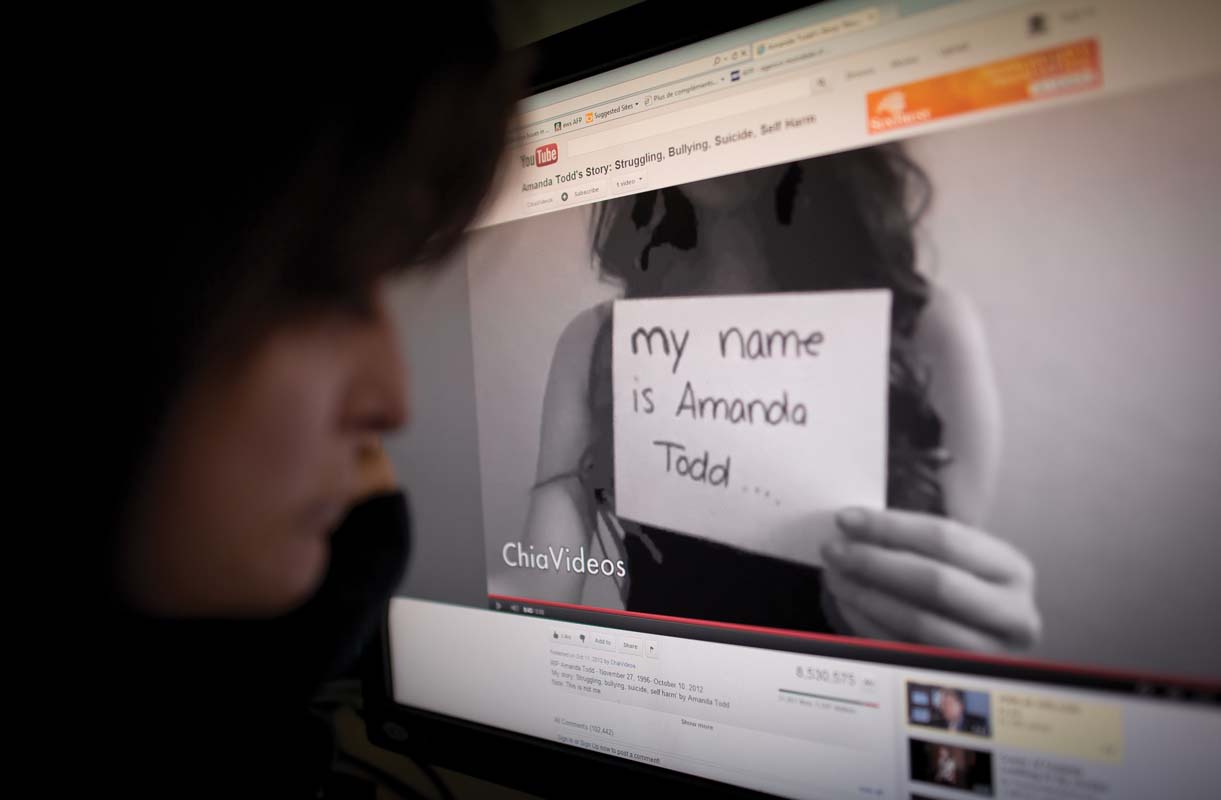

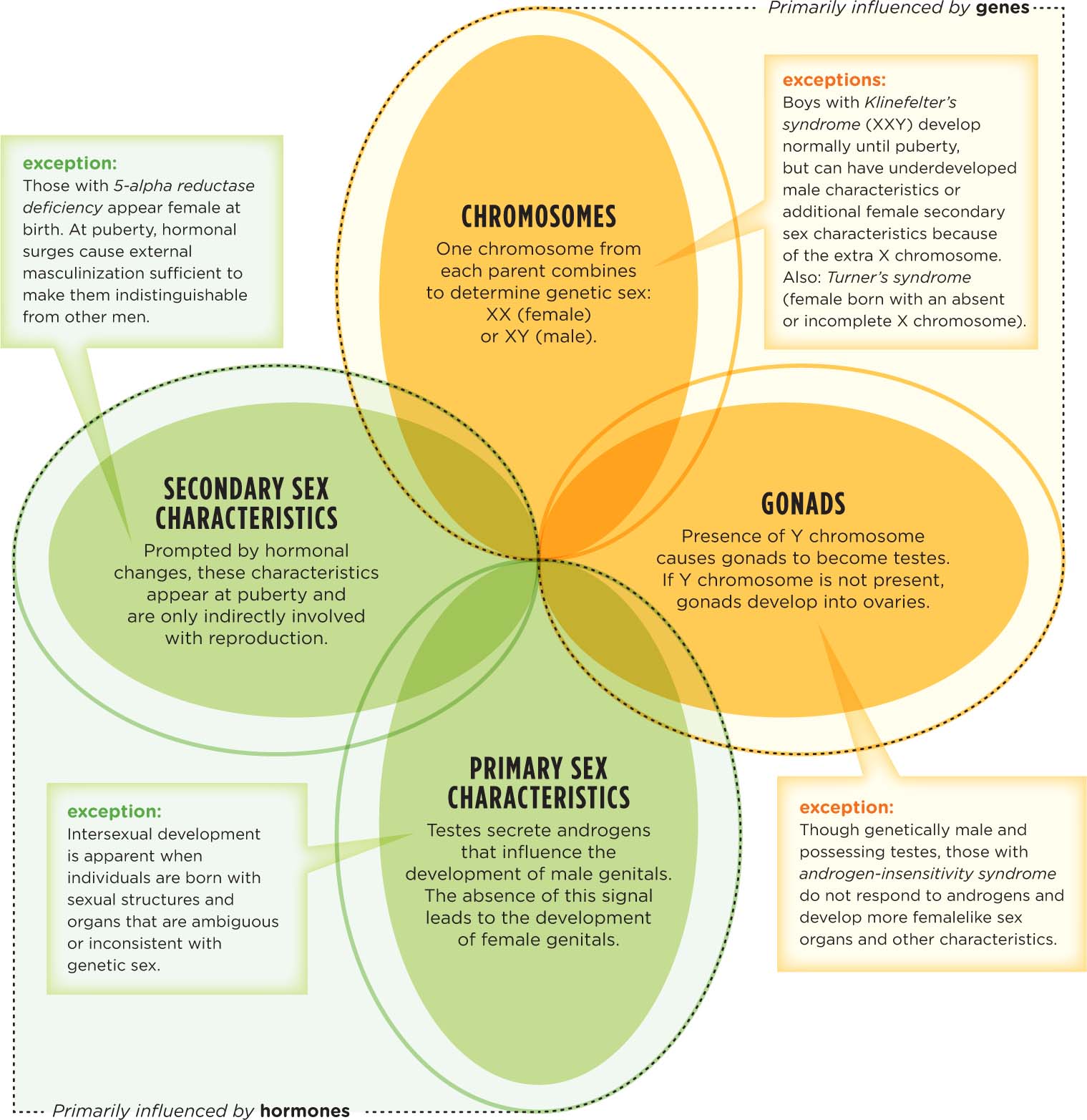

In some cases, hormonal imbalances and genetic abnormalities lead to differences of sex development (Topp, 2013; Infographic 10.1). Such disparities result from “congenital conditions in which development of chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomic sex is atypical” (Lee, Houk, Ahmed, & Hughes, 2006, p. e488). According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013, p. 451), intersexual refers to having “conflicting or ambiguous biological indicators” of male or female in sexual structures and organs (TABLE 10.1). For example, intersexual development would be apparent in a genetic female (XX) or male (XY) who has sexual structures and organs that are ambiguous or inconsistent with genetic sex. Around 1% of infants are found to have differences of sex development at birth. Such an individual might once have been called a “hermaphrodite,” but this term is outdated, derogatory, and misleading because it refers to the impossible condition of being both fully male and fully female (Vilain, 2008).

| Differences of Sexual Development | Frequency |

| Intersex (atypical genitalia) | 1 in 1,500 births |

| Klinefelter’s syndrome | 1 in 1,000 births |

| Turner’s syndrome | 1 in 2,500 female births |

| Androgen-insensitivity syndrome | 1 in 13,000 births |

| 5-alpha reductase deficiency | Very rare—incidence unknown |

| People with ambiguous sexual characteristics are considered to have differences of sexual development. Listed above are the frequency estimates for some common causes of intersexuality. | |

|

SOURCES: GENETICS HOME REFERENCE (2008); INTERSEX SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA (2008); NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH, EUNICE KENNEDY SHRIVER NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF CHILD HEALTH AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT (N.D.). |

|

The roots of intersexuality lie early in development, when fetal sensitivity to hormones determines the path of sexual differentiation, with timing and the amount of hormones as important factors. If a male fetus is insensitive to androgens, for example, he may develop more femalelike sex organs (known as androgen insensitivity syndrome; Mazur, 2005). A fetally androgenized female develops more malelike sex organs as a result of being exposed to excess androgens (Dessens, Slijper, & Drop, 2005).

Chromosomes and Intersexuality

Differences of sexual development can also be traced to irregularities in the sex chromosomes, as the creation of the 23rd pair does not always follow the expected pattern of XX or XY (Juul, Main, & Skakkebaek, 2011; Wodrich & Tarbox, 2008). On some occasions, there are too many chromosomes or one missing. In the case of Klinefelter’s syndrome, a male is born with at least one extra X chromosome in the 23rd pair (for example, XXY). A boy with Klinefelter’s syndrome typically develops normally until puberty, but then has a greater chance of developing female sex characteristics such as breasts. He is infertile or may have underdeveloped sexual organs and secondary sex characteristics (Mandoki, Sumner, Hoffman, & Riconda, 1991; Manning, Kilduff, & Trivers, 2013). In Turner’s syndrome, a female is born with only one X chromosome (as opposed to two X chromosomes), anatomically normal genitals, ovaries that are not fully developed, and infertility. Girls with this syndrome who go undiagnosed or untreated are at increased risk for estrogen deficiency, hypothyroidism, cardiovascular issues, and short stature (Hjerrild, Mortensen, & Gravholt, 2008). Despite the possibility of developmental delays in cognitive, social, and emotional functioning, women with Turner’s syndrome who receive treatment can lead independent, stable, and productive lives (McCauley & Sybert, 2006).

432

INFOGRAPHIC 10.1: Different Layers of Sexual Determination

When thinking about the biological factors that determine sex, most people envision the primary sex characteristics that indicate our assignment at birth. But one’s sex is made up of many layers with different influences. Though they often all combine in a predictable way, there can be exceptions at any point. Looking at variations at each layer demonstrates the complex reality of sex that goes far beyond what is declared on our birth certificates.

433

show what you know

Question 10.1

1. __________ refers to our sexual activities, attitudes, and behaviors.

- Sex

- Sex determination

- Sexuality

- Gender

Question 10.2

2. A physician attempts to explain to a young couple some of the biological factors that determine sex. She states that when the 23rd chromosome pair contains an X and a Y, the zygote generally develops:

- into a female.

- into a male.

- ovaries.

- the anatomy of both sexes.

Question 10.3

3. On occasion, the 23rd pair of chromosomes does not follow the expected pattern and will include too many chromosomes. For example, a person with __________ is born with at least one extra X chromosome.

Question 10.4

4. How are chromosomes involved in differences of sex development?

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.

434