10.2 Gender

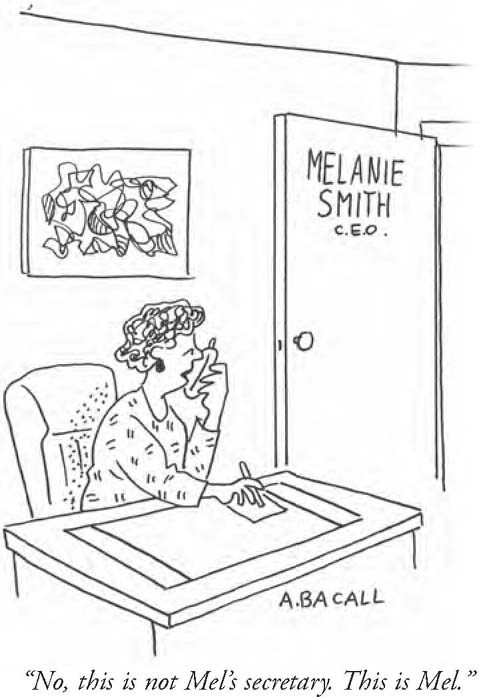

With the prior biology lesson under our belt, let’s consider its implications for psychology. What does it mean to be a “man” or “woman” in today’s world? Many think of men as being assertive, logical, and in charge, whereas women are perceived as more caring, sensitive, and emotional. But such characterizations are simplistic and frequently inaccurate. Just ask Stephen Patten.

A MASCULINE TOUCH

Have you ever been hospitalized? If so, you probably remember your nurses—perhaps better than your doctors. The role of the nurse is extremely important. Nurses are the people who make sure you are clean, comfortable, and properly medicated at all hours of the day. When you press the call button at 2:00 a.m., it is the nurse who appears at your bedside. As you undergo a frightening or painful procedure, it is typically the nurse who holds your hand. Few professions demand such a high level of sensitivity and compassion.

Have you ever been hospitalized? If so, you probably remember your nurses—perhaps better than your doctors. The role of the nurse is extremely important. Nurses are the people who make sure you are clean, comfortable, and properly medicated at all hours of the day. When you press the call button at 2:00 a.m., it is the nurse who appears at your bedside. As you undergo a frightening or painful procedure, it is typically the nurse who holds your hand. Few professions demand such a high level of sensitivity and compassion.

The field of nursing is dominated by women, who are sometimes perceived as being more caring and nurturing than men. But according to Stephen Patten, the ability to care and nurture has little to do with gender. The son of a minister, Stephen was raised to believe that men have the capacity for deep compassion—and he has put this lesson to work in his 32-year career.

Nothing is more rewarding than the nurse–patient relationship, according to Stephen. Nursing, he says, is “the most intimate of any of the health-care professions.” Doctors diagnose and treat diseases (an important job indeed), but the nurse is the patient’s advocate and lifeline. Lying on an operating table unable to move and unconscious, you are in no position to help yourself, but the nurse is there to make sure you are hydrated, to cover you with a warming blanket, and to ensure that hospital staff use proper sterilization techniques so you do not acquire a dangerous infection, among other things.

Some patients are pleasantly surprised to discover a man will be caring and advocating for them in their most vulnerable state. But others have trouble accepting the idea that Stephen could serve in such a capacity. “What are you, some sort of lesbian trapped in a man’s body?” one patient demanded to know. Another flat-out refused to have a male nurse participate in her care. Why do you think these patients reacted to Stephen this way? We suspect it has something to do with their preconceived notions about gender roles.

Gender: Beyond Biology

LO 4 Define gender and explain how culture plays a role in its development.

Earlier we described gender as the dimension of masculinity and femininity based on social, cultural, and psychological characteristics. Men are typically perceived as masculine, and women are assumed to be feminine. But concepts of masculine and feminine vary according to culture, social context, and the individual. We learn how to behave in gender-appropriate ways through the gender roles designated by our culture (although some behavioral differences between males and females are apparent from birth; more on this in a bit). Gender roles are demonstrated through the actions, general beliefs, and characteristics associated with masculinity and femininity. This understanding of expected male and female behavior is generally demonstrated by around age 2 or 3. So too is the ability to differentiate between boys and girls, and men and women (Zosuls, Miller, Ruble, Martin, & Fabes, 2011). Most of us have been the target of a curious toddler, openly asking questions or making comments about sex or gender.

435

A person’s gender identity is the feeling or sense of being either male or female, and compatibility, contentment, and conformity with one’s gender (Egan & Perry, 2001; Tobin et al., 2010). Gender identity is often reinforced by learning and parental stereotyping of appropriate girl/boy behaviors, but does not always follow such a script. Researchers have found that an environment that does not specify strict gender roles results in children developing more fluid ideas about gender-appropriate behavior (Hupp, Smith, Coleman, & Brunell, 2010). Thus, if a child is growing up in a single-parent home, she will likely see her parent taking on the traditional gender roles of both males and females, and will be more comfortable stepping outside the boundaries prescribed by such roles.

Learning and Gender Roles

Gender typing is “the development of traits, interests, skills, attitudes, and behaviors that correspond to stereotypical masculine and feminine social roles” (Mehta & Strough, 2010, p. 251). These gender roles can be acquired through observational learning, as explained by social-cognitive theory (Bussey & Bandura, 1999; Else-Quest, Higgins, Allison, & Morton, 2012; Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2002). We learn from our observations of others in our environment, particularly by watching those of the same gender. Children also learn and model the behaviors represented in electronic media and books (Kingsbury & Coplan, 2012).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we described how learning can occur by observing and imitating a model. Here we see how this type of learning can shape the formation of gender roles.

Operant conditioning is also involved in the development of gender roles. Children often receive reinforcement for behaviors considered gender-appropriate and punishment (or lack of attention) for those viewed as inappropriate. Parents, caregivers, relatives, and peers reinforce gender-appropriate behavior by smiling, laughing, or encouraging. But when children exhibit gender-inappropriate behavior (a boy playing with a doll, for example), the people in their lives might frown, get worried, or even put a stop to it. Through this combination of encouragement and discouragement a child learns to conform to society’s expectations. Keep in mind that not all parents and caregivers are passionate about preserving traditional gender roles.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we discussed operant conditioning, which is learning that results from consequences. Here, the positive reinforcer is encouragement, which leads to an increase in a desired behavior. The punishment is discouragement, which reduces the unwanted behavior.

436

Cognition and Gender Schemas

In addition to learning by observation and reinforcement, children seem to develop gender roles by actively processing information (Bem, 1981). In other words, children think about the behaviors they observe, including the differences between males and females. They watch their parents’ behavior, often following suit (Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2002). Using the information they have gathered, they develop a variety of gender-specific rules they believe should be followed (for example, girls help around the house, boys play with model cars; Yee & Brown, 1994). These rules provide the framework for gender schemas, which are the psychological or mental guidelines that dictate how to be masculine or feminine. Gender schemas also impact how we process information or remember events (Barberá, 2003). For example, Martin and Halverson (1983) found that children were more likely to remember events incorrectly if those events violated gender stereotypes. If they saw a little girl playing with a truck and a little boy playing with a doll, they were likely to recall the girl having the doll and the boy having the truck when tested several days later. In a more recent study, children were asked to recall information from storybooks they had just heard on audiotape. Immediately afterward, their recall of the stories was “often imprecise,” most likely because their notions of gender-appropriate behavior (gender schemas) colored their memories. For example, one of the stories told of a little girl who was trying to help an adult male overcome his fear of walking on a high wire. Yet many children inaccurately remembered the little girl being afraid, or thought that the man was protecting her (Frawley, 2008). Apparently, their gender schemas incorporated the assumption that men are brave, and this interfered with their ability to recall the story correctly.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we stated that schemas are a component of cognition. Schemas are collections of ideas or notions representing a basic unit of understanding. Here, we see a specific type of schema that influences conceptions of gender and memories.

Biology and Gender

Clearly, culture and learning influence the development of gender-specific behaviors and interests, but could biology play a role too? Research on nonhuman primates suggests this is the case (Hines, 2011a). A growing body of literature points to a link between testosterone exposure in utero and specific play behaviors (Swan et al., 2010). For example, male and female infants as young as 3 to 8 months demonstrate gender-specific toy preferences that cannot be explained by mere socialization or learning (Hines, 2011b). Research using eye-tracking technology reveals that baby girls spend more time looking at dolls, while boys tend to focus on toy trucks (Alexander, Wilcox, & Woods, 2009). Although these early differences seem to be unlearned, infants as young as 6 months can learn to discriminate between male and female faces and voices. Perhaps their toy interests have a learned component as well (Martin, Ruble, & Szkrybalo, 2002). But the bottom line is, not all gender-specific behaviors can be attributed to culture and upbringing—a principle well illustrated by the heartbreaking story of Bruce Reimer.

437

Dr. Buehler: What made you choose this field of study?

nature AND nurture

The Case of Bruce Reimer

Bruce Reimer and his twin brother were born in 1965. During a circumcision operation at 8 months, Bruce’s penis was almost entirely burnt away by electrical equipment used in the procedure. When he was about 2 years old, his parents took the advice of Johns Hopkins psychologist John Money and decided to raise Bruce as a girl (British Broadcasting Company [BBC], 2005, September). The thinking at the time was that what made a person a male or female was not necessarily the original structure of the genitals, but rather how he or she was raised (Diamond, 2004).

Bruce Reimer and his twin brother were born in 1965. During a circumcision operation at 8 months, Bruce’s penis was almost entirely burnt away by electrical equipment used in the procedure. When he was about 2 years old, his parents took the advice of Johns Hopkins psychologist John Money and decided to raise Bruce as a girl (British Broadcasting Company [BBC], 2005, September). The thinking at the time was that what made a person a male or female was not necessarily the original structure of the genitals, but rather how he or she was raised (Diamond, 2004).

Just before Bruce’s second birthday, doctors removed his testicles and used the tissues to create the beginnings of female genitalia. His parents began calling him Brenda, dressing him like a girl and encouraging him to engage in stereotypically “girl” activities such as baking and playing with dolls (BBC, 2005, September). But Brenda did not adjust so well to her new gender assignment. An outcast at school, she was called cruel names like “caveman” and “gorilla.” She brawled with both boys and girls alike, and eventually got kicked out of school (CBC News, 2004, May 10; Diamond & Sigmundson, 1997).

When Brenda hit puberty, the problem became even worse. Despite ongoing psychiatric therapy and estrogen replacement, she could not deny what was in her nature—she refused to consider herself female (Diamond & Sigmundson, 1997). Brenda became suicidal, prompting her parents to tell her the truth about the past (BBC, 2005, September).

At age 14, Brenda decided to “reassign himself” to be a male. He then changed his name to David, began taking male hormones, and underwent a series of penis construction surgeries (Colapinto, 2000; Diamond & Sigmundson, 1997). At 25, David married and adopted his wife’s children, and for some time it appeared he was doing quite well (Diamond & Sigmundson, 1997). But sadly, at the age of 38, he took his own life.

HIS PARENTS…DECIDED TO RAISE BRUCE AS A GIRL.

We are in no position to explain the tragic death of David Reimer, but we cannot help but wonder what role his traumatic gender reassignment might have played. Keep in mind that this is just an isolated case. As discussed in Chapter 1, we should be extremely cautious about making generalizations from case studies, which may or may not be representative of the larger population. Many people who undergo sex reassignment go on to live happy and fulfilling lives.

Gender-Role Stereotypes

The case of Bruce Reimer touches on another important topic: gender-role stereotypes. Growing up, David (who was called “Brenda” at the time) did not enjoy wearing dresses and playing “girl” games. He didn’t adhere to the gender-role stereotypes assigned to little girls. Gender-role stereotypes, which begin to take hold around age 3, are strong ideas about the nature of males and females—how they should dress, what kinds of games they should like, and so on. Decisions about children’s toys, in particular, follow strict gender-role stereotypes (boys play with trucks, girls play with dolls), and any crossing over risks ridicule from peers, sometimes even adults. Gender-role stereotypes are apparent in toy commercials (Kahlenberg & Hein, 2010) and pictures in coloring books (Fitzpatrick & McPherson, 2010). They also manifest themselves in academic settings. For example, many girls have negative attitudes about math, which seem to be associated with parents’ and teachers’ expectations about gender differences in math competencies (Gunderson, Ramirez, Levine, & Beilock, 2012).

438

Children, especially boys, tend to cling to gender-role stereotypes very tightly. You are much more likely to see a girl playing with a “boy” toy than a boy playing with a “girl” toy. Society, in turn, is more tolerant of girls who cross gender stereotypes. In many cultures, the actions of a tomboy (a girl who behaves in ways society considers masculine) are more acceptable than those of a “sissy” (a derogatory term for a boy who acts in a stereotypically feminine way; Martin & Ruble, 2010; Thorne, 1993). Despite such judgments, some children do not conform to societal pressure (Tobin et al., 2010).

Androgyny

Those who cross gender-role boundaries and engage in behaviors associated with both genders are said to exhibit androgyny. An androgynous person might be nurturing (generally considered a feminine quality) and assertive (generally considered a masculine quality), thus demonstrating characteristics associated with both genders (Johnson et al., 2006). But concepts of masculine and feminine—and therefore what constitutes androgyny—are not consistent across cultures. In North America, notions about gender are revealed in clothing colors; parents frequently dress boy babies in blue and girl babies in pink. In the African nation of Swaziland, on the other hand, children are dressed androgynously, wearing any color of the rainbow (Bradley, 2011).

Transgender and Transsexual

LO 5 Distinguish between transgender and transsexual.

The development of gender identity and the acceptance of gender roles go relatively smoothly for most people. But sometimes societal expectations of being male or female differ from what an individual is feeling inwardly, leading to discontent. At birth, most people are identified as male or female; this is referred to as an infant’s natal gender, or gender assignment. When natal gender does not feel right, an individual may have transgender experiences. According to the American Psychological Association, transgender refers to people “whose gender identity, gender expression, or behavior does not conform to that typically associated with the sex to which they were assigned at birth” (APA, 2011b. Remember that gender identity is the feeling or sense of being either male or female. For a person who is transgender, a mismatch occurs between that sense of identity and the gender assignment at birth. This disparity can be temporary or persistent (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Approximately 700,000 individuals in the United States (around 0.2% of the population) consider themselves to be transgender (Gates, 2011).

When the discrepancy between natal gender and gender identity leads to significant experiences and/or expression of distress, an individual might meet the criteria for a gender dysphoria diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some transgender individuals try to resolve this discontent through medical intervention. According to the American Psychiatric Association, a person is considered transsexual if he or she seeks or undergoes “a social transition from male to female or female to male, which in many, but not all, cases also involves a somatic transition by cross-sex hormone treatment and genital surgery (sex reassignment surgery)” (APA, 2013, p. 451, italics in original). Transsexual people frequently report they have always had the feeling they were born into the body of a person of the opposite sex. There is a lot of inconsistency in the terminology and labels associated with trans: those who are considered and identify themselves as transgender, transsexual, or nonconforming to traditional gender identities. Thus, we should be sensitive about labeling and, when possible, ask trans people how they would like to be identified (Hendricks & Testa, 2012).

439

As you can see, gender is a complex and intangible social construct. Now let’s tackle something a little more concrete. Are you ready for sex?

show what you know

Question 10.5

1. __________ refers to how masculinity and femininity are defined based on culture, social setting, and psychological characteristics.

- Sex

- Sex role

- Gender schema

- Gender

Question 10.6

2. A sixth-grader states that men are more assertive, logical, and in charge than women. She has learned about this __________ from a variety of sources in her immediate setting and culture.

- gender identity

- observational learning

- gender role

- androgyny

Question 10.7

3. The psychological or mental rules that dictate how to be masculine and feminine are known as __________.

Question 10.8

4. Describe the difference between transgender and transsexual.

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.