13.7 Schizophrenia

Degrees of Psychopathology

LO 8 Recognize the symptoms of schizophrenia.

How would it feel to have voices following you throughout the day, commenting on your behaviors, attacking your character, and taunting you with hurtful remarks: “You’re ugly, you’re worthless, you deserve to die” (Halpern, 2013, p. 2). Meanwhile, your perception of the world is grossly distorted. Nickels, dimes, and pennies all look the same, and the subway you take to class is really on its way to a Nazi concentration camp—or so you believe. These are actual symptoms reported by Lisa Halpern, who suffers from a disabling psychological disorder called schizophrenia (skit-sə-′frē-nē-ə). People with schizophrenia experience psychosis, a loss of contact with reality that is severe and chronic.

Schizophrenia, Take 5

The hallmark features of schizophrenia are disturbances in thinking, perception, and language (TABLE 13.7). Psychotic symptoms include delusions, which are strange or false beliefs that a person maintains even when presented with contradictory evidence. Common delusional themes include being persecuted by others, spied upon, or ridiculed. Some people have grandiose delusions; they may believe they are extraordinarily talented or famous, for example. Others are convinced that radio reports, newspaper headlines, or public announcements are about them. Delusions appear very real to those experiencing them.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| There is a great deal of public confusion about what it means to have schizophrenia. Listed above are some common features of this frequently misunderstood disorder. | |

| SOURCE: DSM–5 (AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION, 2013). | |

People with schizophrenia may also hear voices or see things that are not actually present. This psychotic symptom is known as a hallucination—a “perception-like experience” that the individual believes is real, but that is not evident to others. Hallucinations can occur with any of the senses, but auditory hallucinations are most common. Often they manifest as voices commenting on what is happening in the environment, or using threatening or judgmental language (APA, 2013).

569

The symptoms of schizophrenia are often classified as positive and negative (TABLE 13.8). Positive symptoms are excesses or distortions of normal behavior, and include delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized speech—all of which are generally not observed in people without psychosis. Negative symptoms, on the other hand, refer to the reduction or absence of normal behaviors. Common negative symptoms are social withdrawal, diminished speech or speech content, limited emotions, and loss of energy and follow-up (Tandon, Nasrallah, & Keshavan, 2009).

| Positive Symptoms of Schizophrenia | Negative Symptoms of Schizophrenia |

|---|---|

| Delusions | Decreased emotional expression |

| Hallucinations | Lack of motivation |

| Disorganized speech | Decreased speech production |

| Grossly disorganized behavior | Reduced pleasure |

| Abnormal motor behavior | Lack of interest in interacting with others |

| Schizophrenia symptoms can be grouped into two main categories: Positive symptoms indicate the presence of excesses or distortions of normal behavior; negative symptoms refer to a reduction in normal behaviors and mental processes. | |

| SOURCE: DSM–5 (AMERICAN PSYCHIATRIC ASSOCIATION, 2013). | |

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we noted that the term positive does not always mean “good.” Positive punishment means the addition of an aversive stimulus. Positive symptoms refer to additions or excesses, not an evaluation of the “goodness” of the symptoms. Negative refers to the reduction or absence of behaviors, not an evaluation of the “badness” of the symptoms.

To be diagnosed with schizophrenia, a person must display symptoms for the majority of days in a 1-month period and experience significant dysfunction with respect to work, school, relationships, or personal care for at least 6 months. (And it must be determined that these problems do not result from substance abuse or a serious medical condition.) DSM–5 introduced a major change in how schizophrenia is diagnosed, as the new edition no longer includes the subtypes used in previous editions (paranoid, disorganized, catatonic, undifferentiated, and residual). With the new edition, clinicians can rate the presence and severity of symptoms (hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, unusual psychomotor behaviors, and negative symptoms).

With estimates ranging from a 0.3–1% lifetime risk, schizophrenia is relatively unusual (APA, 2013; Saha, Chant, Welham, & McGrath, 2005). Although men and women appear to be equally likely to be affected (Abel, Drake, & Goldstein, 2010; Saha et al., 2005), the onset of the disorder tends to occur earlier in men. Males are typically diagnosed during their late teens or early twenties, whereas the peak age for women is the late twenties (APA, 2013; Gogtay, Vyas, Testa, Wood, & Pantelis, 2011). In most cases, schizophrenia is a lifelong disorder that causes significant disability and a high risk for suicide. The prognosis is worse for earlier onset schizophrenia, but this may be related to the fact that men, who tend to develop symptoms earlier in life, are in poorer condition when first diagnosed (APA, 2013). Furthermore, there is a higher prevalence of schizophrenia among people in lower socioeconomic classes (Tandon, Keshavan, & Nasrallah, 2008).

Untangling the Roots of Schizophrenia

LO 9 Analyze the biopsychosocial factors that contribute to schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is a complex psychological disorder that results from a perfect storm of biological, psychological, and social factors. Because this disorder springs from a complex interaction of genes and environment, researchers have a hard time predicting who will be affected.

570

For many years, various experts focused the blame on environmental factors, such as unhealthy family dynamics and bad parenting. A common scapegoat was the “schizophrenogenic mother,” whose poor parenting style was believed to cause the disorder in her child (Harrington, 2012). Thankfully, this belief has been shattered by our new understanding of the brain. Schizophrenia is now one of the most heavily researched psychological disorders, with approximately 5,000 new articles added to the search databases every year (Tandon et al., 2008)! Among the most promising areas of research is the genetics of schizophrenia. It turns out that schizophrenia runs in families, and few cases illustrate this principle better than that of the Genain sisters.

nature AND nurture

Four Sisters

Nora, Iris, Myra, and Hester Genain were identical quadruplets, born in 1930. Their mother went to great lengths to treat them equally, and in many ways the children were equals (Mirsky & Quinn, 1988). As babies, they cried in unison and teethed at the same times. As toddlers, they played with the same toys, wore the same dresses, and rode the same tricycles. The little girls were said to be so mentally in sync that they never argued (Quinn, 1963).

Nora, Iris, Myra, and Hester Genain were identical quadruplets, born in 1930. Their mother went to great lengths to treat them equally, and in many ways the children were equals (Mirsky & Quinn, 1988). As babies, they cried in unison and teethed at the same times. As toddlers, they played with the same toys, wore the same dresses, and rode the same tricycles. The little girls were said to be so mentally in sync that they never argued (Quinn, 1963).

Mr. and Mrs. Genain kept the girls isolated. Spending most of their time at home, the quads cultivated few friendships and didn’t go out with boys. The Genains may have protected their daughters from the world outside, but they could not shield them from the trouble brewing inside their brains.

At age 22, one of the sisters, Nora, was hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder characterized by hallucinations, delusions, altered speech, and other symptoms. Within months, a second sister, Iris, was admitted to a psychiatric ward as well. She, too, had the symptoms of psychosis. Both Nora and Iris were diagnosed with schizophrenia, and it was only a matter of years before Myra and Hester joined them (Mirsky & Quinn, 1988). What are the odds of a birth resulting in identical quadruplets who would all develop schizophrenia? One in 1.5 billion, according to one scholar’s estimate (Mirsky et al., 2000). As you can imagine, the case of the Genain quads has drawn the attention of many scientists. David Rosenthal and his colleagues at the National Institute of Mental Health studied the women when they were in their late twenties and again when they were 51. To protect the quads’ identities, Rosenthal assigned them the pseudonyms Nora, Iris, Myra, and Hester, which spell out NIMH, the acronym for the National Institute of Mental Health. Genain is also an alias, meaning “dreadful gene” in Greek (Mirsky & Quinn, 1988).

LIKE ANY PSYCHOLOGICAL PHENOMENON, SCHIZOPHRENIA IS A PRODUCT OF BOTH NATURE AND NURTURE.

The Genain sisters are genetically equal, which suggests that there is some heritable component to their schizophrenia. Yet, each woman experiences the disorder in her own way. Hester did not receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia until she was in her twenties, but she started to show signs of psychological impairment much earlier than her sisters and was never able to hold down a job or live alone. Myra, however, has been employed for the majority of her life and has a family of her own (Mirsky et al., 2000; Mirsky & Quinn, 1988). Like any psychological phenomenon, schizophrenia is a product of both nature and nurture.

Genetic Factors

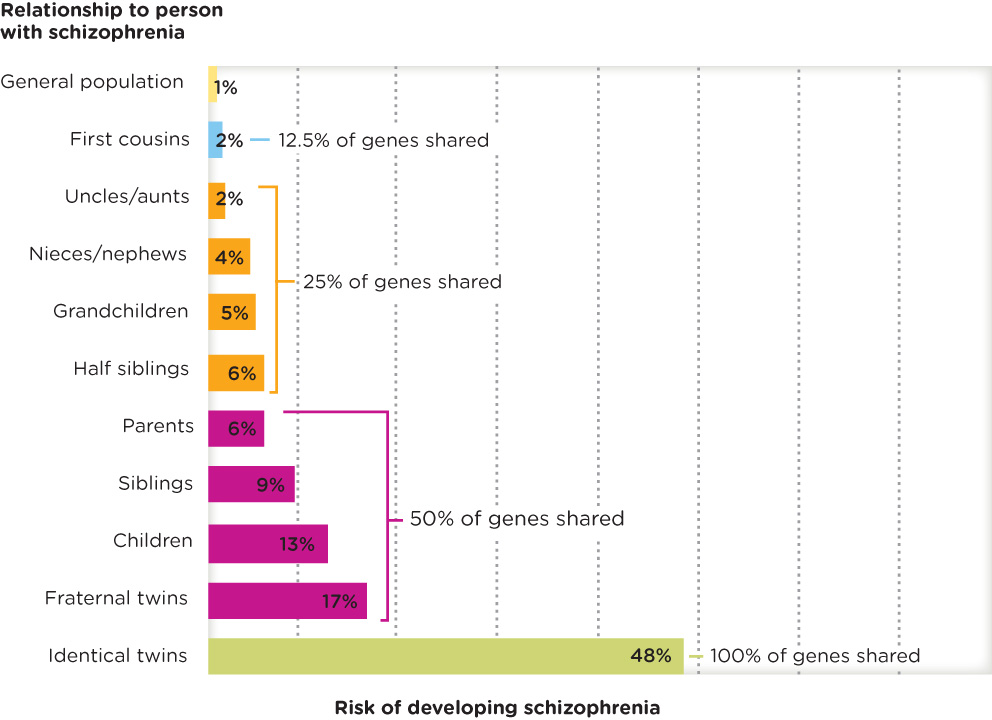

Overall, researchers agree that schizophrenia is “highly heritable,” with genetic factors accounting for around 80% of the risk for developing this disorder (Tandon et al., 2008). Much of the evidence derives from twin, family, and adoption studies (Figure 13.3). If one identical twin has schizophrenia, the risk of the other twin developing the disorder is approximately 41–65% (Petronis, 2004). Compare that to a mere 2% risk for those whose first cousins have schizophrenia (Tsuang, Stone, & Faraone, 2001). If both parents have schizophrenia, the risk of their children being diagnosed with this disorder is 27% (Gottesman, Laursen, Bertelsen, & Mortensen, 2010). Keep in mind that schizophrenia is not caused by a single gene, but by a combination of many genes interacting with the environment (Howes & Kapur, 2009).

571

Diathesis–Stress Model

Like other disorders, schizophrenia is best understood from the biopsychosocial perspective. One model that takes these factors into account is the diathesis–stress model, where diathesis refers to the inherited disposition, for example, to schizophrenia, and stress refers to the stressors and other factors in the environment (internal and external). Identical twins share 100% of their genetic make-up (diathesis), yet the environment produces different stressors for the twins (only one of them loses a spouse, for example). As a result, one twin may develop the disorder, but the other does not. This model suggests that developing schizophrenia involves a genetic predisposition and environmental triggers.

The Brain

People with schizophrenia generally experience a thinning of the cortex, leading to enlarged ventricles, the cavities in the brain that are filled with cerebrospinal fluid. Research also shows that the total volume of the brain is reduced in schizophrenia (Tandon et al., 2008). In general, these abnormalities are thought to be related to problems with “cognitive control” and psychotic symptoms (Glahn et al., 2008). A word of caution when interpreting these findings, however: It is possible that differences in brain structures are not just due to schizophrenia; they may also result from long-term use of medications to control its symptoms (Jaaro-Peled, Ayhan, Pletnikov, & Sawa, 2010).

572

Neurotransmitter Theories

Evidence suggests that abnormal neurotransmitter activity plays a role in schizophrenia. According to the dopamine hypothesis, the synthesis, release, and concentrations of dopamine are all elevated in people who have been diagnosed with schizophrenia and are suffering from psychosis (van Os & Kapur, 2009). Support for the dopamine hypothesis comes from the successful use of medications that block the receptor sites for dopamine. These drugs reduce the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia, presumably because they decrease the potential impact of the excess dopamine being produced (van Os & Kapur, 2009).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we discussed activity at the synapse. When neurotransmitters are released, they must bind to receptor sites in order to relay their message to the receiving neuron (“fire” or “don’t fire”). Medications that block or inhibit the receptor sites on the receiving neuron are referred to as antagonists, and some of these are used to reduce symptoms of schizophrenia.

Although the effect of increased dopamine has not been precisely determined, one suggestion is that it influences the “reward system” of the brain. Excess dopamine may make it hard for people to pay attention to what is rewarding in the environment, or pick out its most salient, or important, aspects (van Os & Kapur, 2009). They often focus on environmental stimuli that lead them to lose touch with reality. So, when they experience delusions, it is possible they are trying to make sense of the salient experiences on which they are focused. Hallucinations might result from placing too much importance on some of their “internal representations” (Kapur, 2003).

The dopamine hypothesis has evolved over the last several decades, with many researchers coming to appreciate the ongoing dynamic between neurochemical processes as they relate to the individual in the environment. We cannot just study what dopamine does in the synapse; we must take into consideration how dopamine’s irregularities are affected by the individual’s interactions within the environment (Howes & Kapur, 2009).

Environmental Triggers and Schizophrenia

Some experts suspect that schizophrenia is associated with exposure to a virus in utero, such as human papilloma virus (HPV). Several illnesses a woman can contract while pregnant, including genital reproductive infections, influenza, and some parasites, may increase her baby’s risk of developing schizophrenia later in life (Brown & Patterson, 2011). Retrospective evidence (that is, information collected much later) suggests that the offspring of mothers who were exposed to viruses while pregnant are more likely to develop schizophrenia as adolescents. However, research on this theory is still ongoing and must be replicated.

Schizophrenia is not the result of poor parenting; nor is it a product of classical or operant conditioning. That being said, there are some sociocultural and environmental factors that may play a minor role in one’s risk for developing the disorder, as well as the severity of symptoms. Evidence exists, for instance, that complications at birth, social stress, and cannabis abuse are related to a slightly increased risk of schizophrenia onset (Tandon et al., 2008).

We now turn our focus to another type of disorder that is intimately connected to one of psychology’s core areas of study: personality.

show what you know

Question 13.20

1. A loss of contact with reality is referred to as __________.

Question 13.21

2. A woman with schizophrenia reports hearing voices that tell her she is ugly and worthless. This is an example of a(n):

- hallucination.

- delusion.

- negative symptom.

- diathesis.

Question 13.22

3. What are some biopsychosocial factors that contribute to the development of schizophrenia?

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.

573