15.6 Attraction and Love

Less than a year after meeting Susanne, Joe purchased an engagement ring. He carried it around in his pocket for 3 months, and then proposed to her one morning over breakfast. They have been happily married for over 5 years. Some things have changed since that rendezvous at Chili’s 8 years ago. Joe left the ice cream business for a corporate career, little Kristina is now a teenager, and Susanne gave birth to TRIPLETS in February 2013—two boys and a girl.

Other things remain the same, like Joe’s goofy sense of humor. He still strolls into the supermarket singing at the top of his lungs and tells people “good morning” when it’s 11 o’clock at night. “I’m a big kid,” Joe says, “but you know when it comes to my family, it’s all about making sure that they are happy and making sure that they are taken care of, and that’s my only priority in life.”

Interpersonal Attraction

LO 12 Identify the three major factors contributing to interpersonal attraction.

It seems Joe and Susanne have made a very happy life for themselves. Things can get hectic with three infant triplets and a teen, but they seem content and able to cope with whatever challenges may arise. Joe and Susanne make a great team. How do you explain their compatibility? We suspect it has something to do with interpersonal attraction, the factors that lead us to form friendships or romantic relationships with others. What are these mysterious attraction factors? Let’s focus our attention on the three that are most important: proximity, similarity, and physical attractiveness.

We’re Close: Proximity

We would guess that the majority of people in your social circle live nearby. Proximity, or nearness, plays a significant role in the formation of our relationships. The closer two people live geographically, the greater the odds that they will meet and spend time together, and the more likely they are to establish a bond (Festinger, Schachter, & Back, 1950; Nahemow & Lawton, 1975). One study looking at the development of friendships in a college classroom setting concluded that sitting in nearby seats and being assigned to the same work groups correlated with the development of friendships (Back, Schmukle, & Egloff, 2008). In other words, sitting next to someone in class, or even in the same row, increases the chances that you will become friends. Would you agree?

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described how researchers examine relationships between two variables. A correlation does not necessarily mean one variable causes changes in the other. What other factors might be influencing friendships to develop in the classroom?

Notions of proximity have changed since the introduction of the Internet. Thanks to applications like Skype and Google Hangouts, we can now have face-to-face conversations with people who are thousands of miles away. Online dating sites offer similar capabilities through chats and instant messaging. They also offer the option of geographic filtering, allowing users to narrow their searches to people who live in a certain zip code or city. But do all these new tools really improve the way people relate to one another? For Joe and Susanne, the answer seems to be “yes.” If it weren’t for Match.com, their paths probably would not have crossed. As for the rest of humanity, the answer is not so straightforward.

SOCIAL MEDIA and psychology

The great advantage of online dating, according to researchers, is that it broadens the dating pool, providing users with opportunities to meet people they never would encounter offline (Finkel et al., 2012). What other medium offers a safe way to browse through thousands, if not millions, of potential partners and prescreen candidates based on a slew of personal data?

The great advantage of online dating, according to researchers, is that it broadens the dating pool, providing users with opportunities to meet people they never would encounter offline (Finkel et al., 2012). What other medium offers a safe way to browse through thousands, if not millions, of potential partners and prescreen candidates based on a slew of personal data?

661

LOOKING FOR LOVE IN ELECTRONIC PLACES.

There are drawbacks, however, like the tendency for many online daters to focus on profile pictures and other superficial details. Also, don’t count on the compatibility algorithms many online dating sites advertise, as researchers are skeptical of them (Finkel, et al., 2012). Despite these shortcomings, relationships that start on these sites are surprisingly successful. According to one study, around 20% of couples who met online had formed lasting relationships, defined as married, engaged, or living together (Bargh & McKenna, 2004).

You may be wondering how social media sites such as Facebook affect interpersonal bonds. Research suggests that many people use social media to enhance the relationships they already have (Anderson, Fagan, Woodnutt, & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2012). Teenagers, in particular, use social networking sites to make contact with their “offline” friends. Their online activities are primarily social (communicating as opposed to playing video games, for example) and seem to reinforce existing friendships (Reich et al., 2012).

Mere-Exposure Effect

These repeated contacts with friends serve a purpose; the mere-exposure effect suggests that the more we are exposed to people, food, jingles, songs, politics, or music, the more positive a reaction we have toward them. More time spent online with friends can strengthen relationships, merely through exposure.

The mere-exposure effect may, to a certain extent, explain why Joe and Susanne are more in love today than they were 8 years ago. After years of positive exposure to one another (living under the same roof, raising children together, and sharing new experiences), their connection has deepened.

Believe it or not, the mere-exposure effect also appears to affect your perception of your own face. Think of how many times you have looked at yourself in the mirror. How do you think that repeated exposure impacts your estimation of your attractiveness? In one study, researchers showed students pictures of themselves and the reversed, or mirror image, versions of those photos. Amazingly, students preferred the reversed image—the one they see every time they look in the mirror—to the “normal” photo. Yet, the opposite was true when the pictures were shown to their friends; they, too, preferred the image they repeatedly see (Mita, Dermer, & Knight, 1977).

But here’s the flip side. Repeated negative exposures may lead to stronger distaste. If a person you frequently encounter has annoying habits or uncouth behavior, negative feelings might develop, even if your feelings were initially positive (Cunningham, Shamblen, Barbee, & Ault, 2005). This could be problematic for romantic relationships. All those minor irritations you overlooked early in the relationship can evolve into major headaches.

Similarity

Perhaps you have heard the saying “birds of a feather flock together.” This statement alludes to the concept of similarity, another factor that contributes to interpersonal attraction (Moreland & Zajonc, 1982; Morry, Kito, & Ortiz, 2011). We tend to prefer those who share our interests, viewpoints, ethnicity, values, and other characteristics. Even age, education, and occupation tend to be similar among those who are close (Lott & Lott, 1965).

662

Physical Attractiveness

We probably don’t need to tell you that physical attractiveness plays a major role in interpersonal attraction (Eastwick, Eagly, Finkel, & Johnson, 2011; Lou & Zhang, 2009). But here is the question: Is beauty really in the eye of the beholder or do people from different cultures and historical periods generally see eye to eye? There is some degree of consistency in the way people rate facial attractiveness (Langlois et al., 2000), with facial symmetry generally considered an attractive trait (Grammer & Thornhill, 1994). But some aspects of beauty do appear to be culturally distinct (Gangestad & Scheyd, 2005). In some parts of the world, people go to great lengths to elongate their necks, increase height, pierce their bodies, augment their breasts, enlarge or reduce the size of their waists, and paint themselves—just so others within their culture will find them attractive. In America, the ideal body shape for women has changed over the years (think of Marilyn Monroe versus Jennifer Aniston), suggesting that cultural concepts of beauty can morph over time.

Looking Good in Those Genes: The Evolutionary Perspective

Why is physical attractiveness so important? Beauty is a sign of health, and healthy people have greater potential for longevity and successful breeding (Gangestad & Scheyd, 2005). Consider this evidence: Women are more likely to seek out men with healthy-looking physical characteristics when they are experiencing peak fertility and are likely to conceive. Ovulating women tend to look for masculine characteristics that suggest a genetic advantage, such as facial symmetry and social dominance, in order to provide the greatest benefit to offspring. This type of man can provide good genes, meaning his offspring have a greater chance of being healthy, attractive, and living longer, but will he stick around and help raise children?

One group of researchers used this “evolutionary explanation” to explore why women might seek out “sexy cads,” or men who are unlikely to take care of their children. Female undergraduate students were asked to participate in what they believed was a study on how their health influenced their mate selection. The women were asked to provide several urine samples to determine when they were ovulating. In one of the research settings, women viewed pictures of physically attractive and average-looking men. The physically attractive men were charismatic and adventurous, and the average-looking men were reliable, stable, and good providers—or so the women were told. When the women were ovulating, they tended to believe that the sexy cads (physically attractive and charismatic men) would actually be more devoted fathers and partners than the “nice” reliable men (Durante, Griskevicius, Simpson, Cantú, & Li, 2012). The implication is that women may choose more attractive-looking men even when it is not in their best interest to do so. You can probably think of some films that portray women making these types of choices. More often than not, such movies have happy endings. Do you think this is what usually happens in real life?

Beauty Perks

Physically attractive people seem to have more opportunities. Beauty is correlated with how much money someone makes, the type of job she holds, and overall success (Pfeifer, 2012). Good-looking children and adults are viewed as more intelligent and more popular, and are treated better in general (Langlois et al., 2000). Why would this be? From the perspective of evolutionary psychology, all these characteristics would be good indicators of reproductive potential. And many people fall prey to the halo effect, or the tendency to assign excessive weight to one dimension of a person. This concept was originally described by Thorndike in 1920 as it related to the evaluation of others. People tend to form these general impressions early on and then cling to them, even in the absence of supporting evidence, or the presence of contradictory evidence (Aronson, 2012). The way we respond to beautiful people is one example of the halo effect; our initial impression of their beauty may lead us to assume they have other positive characteristics like superior intelligence, popularity, and desirability.

663

Beauty may captivate you in the beginning stages of a relationship, but other characteristics and qualities gain importance as time goes along. Think about the type of person you want for a life partner. Whom would you want to hold your hand when you’re sick in the hospital—the lingerie model or the person you most respect and trust?

What Is Love?

In America, we are taught to believe that love is the foundation of marriage. People in Western cultures do tend to marry for love, but this is not the case everywhere. In Harare, Zimbabwe, for example, people might also marry for reasons associated with the needs of the family, such as maintaining alliances and social status (Wojcicki, van der Straten, & Padian, 2010). Similarly, many marriages in India and other parts of South Asia are arranged by family members. Love may not be present in the beginning stages of such alliances, but it can blossom.

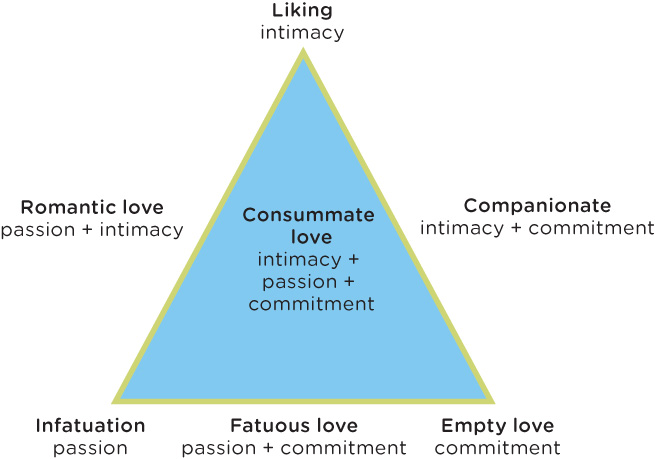

Sternberg’s Theory of Love

In a pivotal study published in 1986, Robert Sternberg proposed that love is made up of three elements: passion (feelings leading to romance and physical attraction); intimacy (feeling close); and commitment (the recognition of love). He conceptualized these elements in terms of the corners of a triangle (Figure 15.4). Love comes in many varieties, according to Sternberg, and can include any combination of the three elements.

Many relationships begin with exhilaration and intense physical attraction, and then evolve into more intimate connections. This is the type of love we often see portrayed in the movies. The combination of connection, concern, care, and intimacy is what Sternberg called romantic love. Romantic love is similar to what some psychologists refer to as passionate love (also known as “love at first sight”), or love that is based on zealous emotion, leading to intense longing and sexual attraction (Hatfield, Bensman, & Rapson, 2012). As a relationship grows, intimacy and commitment develop into companionate love, or love that consists of profound fondness, camaraderie, understanding, and emotional closeness. Companionate love is typical of a couple that has been together for many years. They become comfortable with each other, routines set in, and passion often fizzles (Aronson, 2012). Although the passion may wane, the friendship is strong. Consummate love (kān(t)-sə-mət) is evident when intimacy and commitment are accompanied by passion. The ultimate goal is to maintain all three components of the triangle.

Research and life experiences tell us that relationships inevitably change. Romantic love is generally what drives people to commit to one another (Berscheid, 2010). But the passion associated with this stage generally decreases over time. That does not mean it cannot reemerge, however. Can you think of ways this passion might be rekindled—a romantic night out, some sexy new underwear, a trip to fantasy-land? Companionate love, in contrast, tends to grow over time. As we experience life with a partner, it is companionate love that seems to endear us to one another (Berscheid, 2010).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we discussed sensory adaptation, which refers to the way in which sensory receptors become less sensitive to constant stimuli. In Chapter 5, we presented the concept of habituation, which occurs when an organism becomes less responsive to repeated stimuli. Humans seem to be attracted to novelty, which might underlie our desire for passion.

What type of love do you think online dating sites tend to select for? Is it companionate love (SF loves to garden, looking for someone who…)? Or is it passionate love (SM looking for a good time with no strings attached…)? As Joe can attest, passionate love was present from the beginning of his relationship with Susanne (he jokes about taking a few cold showers before anything happened). Although their passion is still strong and steady, the love and respect they have for one another have grown much deeper.

664

Have you ever wondered about the long-term stability of your relationships? Couples stay together for many reasons, some better than others. Caryl Rusbult’s investment model of commitment focuses on the resources at stake in relationships, including finances, possessions, time spent together, and perhaps even children (Rusbult, 1983). According to this model, decisions to stay together or separate are based on how happy people are in their relationship, their notion of what life would be like without it, and their investment. According to the investment model of commitment (Rusbult & Martz, 1995), people may stay in unsatisfying or unhealthy relationships if they feel there are no better alternatives or believe they have too much to lose. This model helps us understand why people remain in destructive relationships.

Making This Chapter Work for You

At last, we reach the end of our journey through social psychology. We hope that what you have learned in this chapter will come in handy in your everyday social exchanges. Be conscious of the attributions you use to explain the behavior of others—are you being objective or falling prey to self-serving bias? Be mindful of your attitudes—how are they influencing your behavior? Know that your behaviors are constantly being shaped by your social interactions—both as an individual and as a member of groups. Understand the dangers of stereotyping, and know the human suffering caused by aggression. But perhaps most of all, be kind and helpful to others, and allow yourself to experience love.

show what you know

Question 15.19

1. What are the three major factors that play a role in interpersonal attraction?

- social influence; obedience; physical attractiveness

- proximity, similarity, physical attractiveness

- obedience; proximity; social influence

- proximity; love; social influence

Question 15.20

2. Research has shown that most people prefer looking at pictures of their own faces when reversed, but friends prefer normal, nonreversed photos. This finding supports the __________, suggesting repeated viewing of one’s face in the mirror makes it more attractive.

Question 15.21

3. We described how the investment model of commitment can be used to predict the long-term stability of a romantic relationship. How can you use this same model to predict the long-term stability of friendships, positions at work, or loyalty to institutions?

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.

CHECK YOUR ANSWERS IN APPENDIX C.