10.3 Humanistic, Learning, and Trait Theories

We have thus far discussed the psychoanalytic theories of personality development, which emphasize the importance of factors beyond one’s control. You don’t get to choose the identity of your parents, the dynamics within your family, or the nature of your childhood conflicts. Nor do you have the ability to direct unconscious activities. If you’re looking for a perspective that emphasizes greater control and self-

The Brighter Side: Maslow and Rogers

CONNECTIONS

The behaviorists, presented in Chapter 1 and Chapter 5, suggested that our behaviors are shaped by factors in the environment. Because of this, we are at the mercy of forces beyond our control. The humanists challenged this position.

The humanistic perspective began gaining momentum in the 1960s and 1970s in response to the negative, mechanistic view of human nature apparent in other theories. According to the humanists, not only are we innately good, we are also in control of our destinies, and these positive aspects of human nature drive the development of personality. According to leading humanists Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers, our natural tendency is to grow in a positive direction.

LO 6 Summarize Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, and describe self-

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs was introduced in Chapter 9, in reference to motivation. According to Maslow, behaviors are motivated by needs. If a basic need is not being met, we are less likely to meet needs higher in the hierarchy. Here, we see how Maslow’s hierarchy can be used to understand personality.

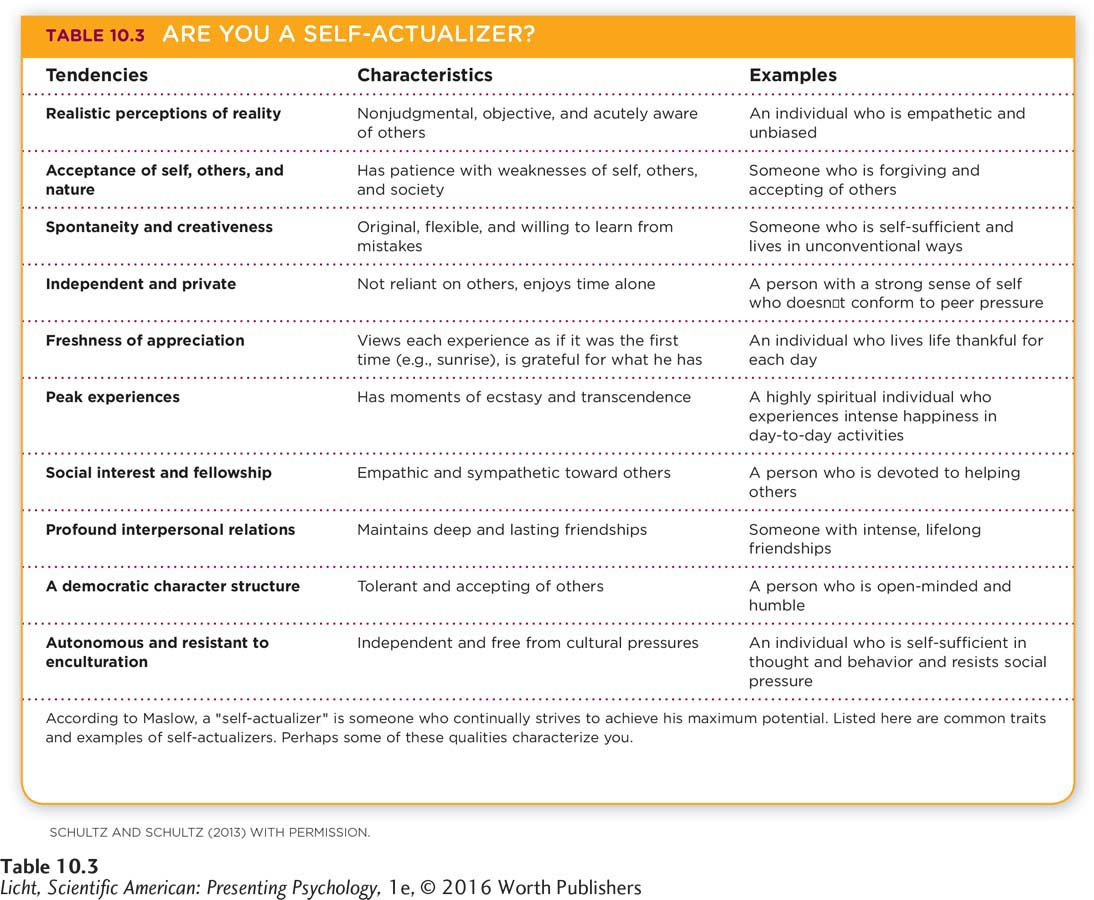

MASLOW AND PERSONALITY Abraham Maslow (1908–

419

Apply This

Pope Francis greets residents of the Varginha shantytown in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The leader of the Catholic Church is known for his humility and commitment to helping the poor. He is the type of person Maslow might have called a “self-

420

LO 7 Discuss Rogers’ view of self-

Amy Chua poses with her daughters at home in New Haven, Connecticut. This Yale law professor is best-

ROGERS AND PERSONALITY Carl Rogers (1902–

self-

ideal self The self-

Rogers highlighted the importance of self-

unconditional positive regard According to Rogers, the total acceptance or valuing of a person, regardless of behavior.

Like Freud, Rogers believed caregivers play a vital role in the development of personality and self-

An Appraisal of the Humanistic Theories

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described positive psychology as a relatively new approach. The humanists’ optimism struck the right chord with many psychologists, who wondered why the field was not focusing on human strengths and virtues.

Let’s step back and review the potential weaknesses of the humanistic approach. For humanistic and psychoanalytic theories alike, creating operational definitions can be challenging. How can you use the experimental method to test a subjective approach whose concepts are open to interpretation (Schultz & Schultz, 2013)? Imagine submitting a research proposal that included two randomly assigned groups of children: one group whose parents were instructed to show them unconditional positive regard and the other group whose parents were told to instill conditions of worth. The proposal would never amount to a real study, not only because it raises ethical issues, but also because it would be impossible to control the experimental conditions. Another problem with unconditional positive regard in particular is that constantly praising, attempting to boost self-

Learning and Social-

421

ROBOTS CAN LEARN, TOO Tank the Roboceptionist is very good at what he does (providing room numbers, directions, weather forecasts, and so on), and he can respond to a range of unexpected remarks and questions in character with his persona. Say “I love you,” and he will shoot back with something like, “That’s nice, but you don’t even know me.” Assault his keyboard with offensive remarks such as “I hate you!” and “@#?! you!” and he will tell you that you are not being very nice. But Tank’s persona and everything he says are predetermined by the human beings who created him. Imagine if Tank could craft his own witty responses from scratch. And wouldn’t it be something if he could learn from his environment and independently develop new skills?

ROBOTS CAN LEARN, TOO Tank the Roboceptionist is very good at what he does (providing room numbers, directions, weather forecasts, and so on), and he can respond to a range of unexpected remarks and questions in character with his persona. Say “I love you,” and he will shoot back with something like, “That’s nice, but you don’t even know me.” Assault his keyboard with offensive remarks such as “I hate you!” and “@#?! you!” and he will tell you that you are not being very nice. But Tank’s persona and everything he says are predetermined by the human beings who created him. Imagine if Tank could craft his own witty responses from scratch. And wouldn’t it be something if he could learn from his environment and independently develop new skills?

A student at the Edinburgh International Science Festival interacts with a robot that is capable of developing game strategies. This robot is engaging the student in “rock-

It turns out that robots can “learn” to some degree. For example, researchers have fashioned robots that can take a collection of objects and categorize them according to the sounds they make when shaken, dropped, or manipulated in other ways (Smith, 2009, March 23). HERB (the Home Exploring Robot Butler) can learn to find his way through messy rooms (Srinivasa et al., 2009). There are also robots that demonstrate observational learning, imitating simple human behaviors like head movements and hand gestures (Breazeal & Scassellati, 2002).

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we described operant conditioning, the type of learning that occurs when we make connections between behaviors and their consequences. The robot’s exiting is followed by a signal, which serves as a reinforcer. But unlike Thorndike’s cats, the robot cannot experience “pleasurable” outcomes. It is programmed to respond to outcomes in a predetermined way.

One very popular area of robot research is “reinforcement learning,” according to Dr. Simmons. Here’s a hypothetical example of how it might work. Researchers program a robot to have some goal, such as exiting a room. The robot begins the task by randomly moving around (not unlike Thorndike’s cats from Chapter 5), but eventually it will come upon a path that leads to an exit. Upon leaving the room, the robot gets a signal indicating that the behavior should be repeated. With continued reinforcement through signals received for correct behavior, the robot tends to make fewer errors and reaches the exit more quickly. Over time, its average performance improves. But like most robot-

With improvements in technology and computer programming, is it possible that robots might one day be capable of possessing personality? If you asked a follower of Freud, we suspect the answer would be a forceful “no.” Robots do not have unresolved conflicts from childhood; in fact, they don’t even have childhoods (remember, the story of Tank is just a human invention). A robot cannot dream, feel sexual urges, or repress unwanted thoughts. Ask a strict behaviorist if robots of the future might be capable of having personality, and you might get a very different answer.

422

LO 8 Use learning theories to explain personality development.

Behaviorists like B. F. Skinner were not interested in studying the thoughts and emotions typically equated with expressions of personality. They focused on measuring observable behaviors that they believed resulted from learning processes such as classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning. From this perspective, personality is a collection of behaviors, all of which have been shaped through a lifetime of learning.

Let’s look at an example. Think of a friend or classmate who is very outgoing. A behaviorist would suggest she has been consistently reinforced to act this way. She gets positive attention, perhaps a promotion at work, and is surrounded by many friends, all of which reinforce her outgoing behavior. This characteristic, which psychologists might call “extraversion,” is just one of the many dimensions of personality molded by learning. Now apply the behaviorist principle to robots. Learning is the foundation for personality, and robots are capable of learning. Looking at things from this perspective, it seems plausible that robots could develop rudimentary personalities.

Like any theory of personality, behaviorism has limitations. Critics contend that behaviorism essentially ignores anything that is not directly observable and thus portrays humans too simplistically, as passive and unaware of what is going on in their internal and external environments. Julian Rotter (1916–

LO 9 Summarize Rotter’s view of personality.

ROTTER AND PERSONALITY According to Rotter, a key component of personality is locus of control, a pattern of beliefs about where control or responsibility for outcomes resides. If a person has an internal locus of control, she believes that the causes of her life events generally reside within her, and that she has some control over them. For example, such a person would say that her career success depends on how hard she works, not on luck (Rotter, 1966). Someone with an external locus of control believes that causes for outcomes reside outside of him; he assigns great importance to luck, fate, and other features of the environment, over which he has little control. As this person sees it, getting a job occurs when all the circumstances are right and luck is on his side (Rotter, 1966). A person’s locus of control refers to beliefs about the self, not about others.

expectancy A person’s predictions about the consequences or outcomes of behavior.

Rotter also explored how behaviors are influenced by thoughts about the future. Expectancy refers to the predictions we make about the outcomes and consequences of our behaviors (Infographic 10.2). A woman who is considering whether she should confront the manager of a restaurant over a bad meal will decide her next move based on her expectancy: Does she expect to be thrown out the door, or does she believe it will lead to a free meal? In these situations, there is an interaction among expectancies, behaviors, and environmental factors.

423

INFOGRAPHIC 10.2

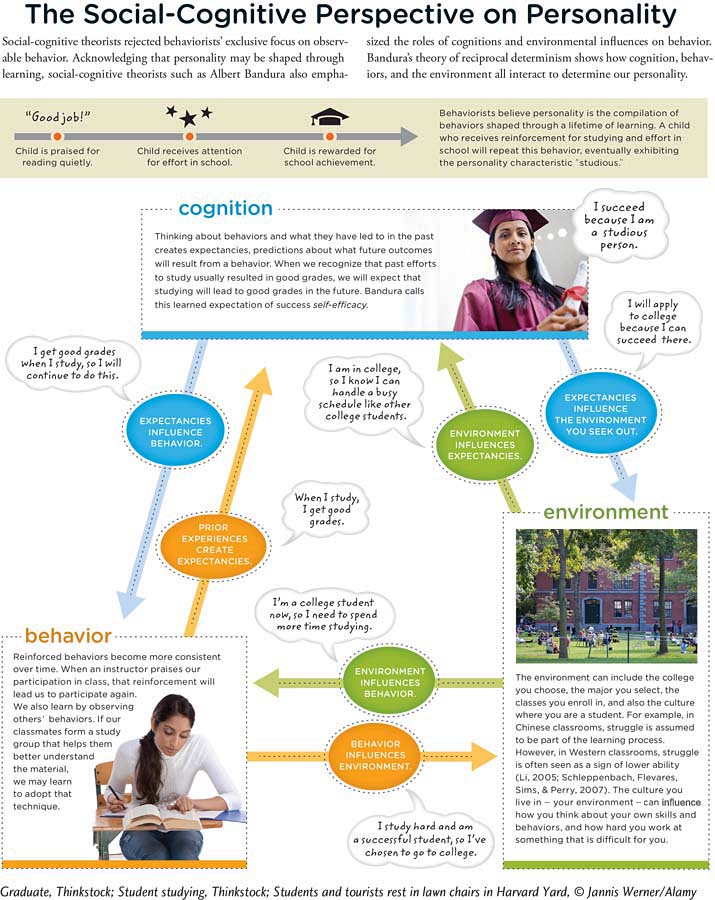

LO 10 Discuss how Bandura uses the social-

social-

BANDURA AND PERSONALITY Another early critic of the behaviorist approach was Albert Bandura (1925–

424

self-

Psychologist Albert Bandura asserts that personality is molded by a continual interaction between cognitions and social interactions, including observations of other people’s behaviors. His approach is known as the social-

Bandura also pointed to the importance of self-

reciprocal determinism According to Bandura, multidirectional interactions among cognitions, behaviors, and the environment.

Beliefs play a key role in our ability to make decisions, problem solve, and deal with life’s challenges. The environment also responds to our behaviors. In essence, we have internal forces (beliefs, expectations) directing our behavior, external forces (reinforcers, punishments) responding to those behaviors, and the behaviors themselves influencing our beliefs and the environment. Beliefs, behavior, and environment form a complex system that determines our behavior patterns and personality (Infographic 10.2 on page 423). Bandura (1978, 1986) refers to this multidirectional interaction as reciprocal determinism.

Let’s use an example to see how reciprocal determinism works. A student harbors a certain belief about herself (I am going to graduate with honors). This belief influences her behavior (she studies hard and reaches out to instructors), which affects her environment (instructors take note of her enthusiasm and offer support). Thus, you can see, personality is the result of an ongoing interaction among cognitions, behaviors, and the environment. Bandura’s reciprocal determinism resembles Rotter’s view. Both suggest that personality is shaped by an ongoing interplay of cognitive expectancies, behaviors, and environment.

TAKING STOCK The learning and social-

Trait Theories and Their Biological Basis

traits The relatively stable properties that describe elements of personality.

trait theories Theories that focus on personality dimensions and their influence on behavior; can be used to predict behaviors.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT TANK If you ask Dr. Reid Simmons to come up with some adjectives to describe Tank the Roboceptionist, he will offer words like “conscientious,” “agreeable,” “reserved,” “naïve,” “loyal,” and “caring.” All of these are examples of traits, the relatively stable properties that describe elements of personality. The trait theories presented here are different from theories discussed earlier in that they focus less on explaining why and how personality develops and more on describing personality and predicting behaviors.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT TANK If you ask Dr. Reid Simmons to come up with some adjectives to describe Tank the Roboceptionist, he will offer words like “conscientious,” “agreeable,” “reserved,” “naïve,” “loyal,” and “caring.” All of these are examples of traits, the relatively stable properties that describe elements of personality. The trait theories presented here are different from theories discussed earlier in that they focus less on explaining why and how personality develops and more on describing personality and predicting behaviors.

425

LO 11 Distinguish trait theories from other personality theories.

ALLPORT AND PERSONALITY One of the first trait theorists was Gordon Allport (1897–

surface traits Easily observable characteristics that derive from source traits.

source traits Basic underlying or foundational characteristics of personality.

CATTELL AND PERSONALITY Raymond Cattell (1905–

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described a correlation as a relationship between two variables. Here, we describe factor analysis, which examines the relationships among an entire set of variables.

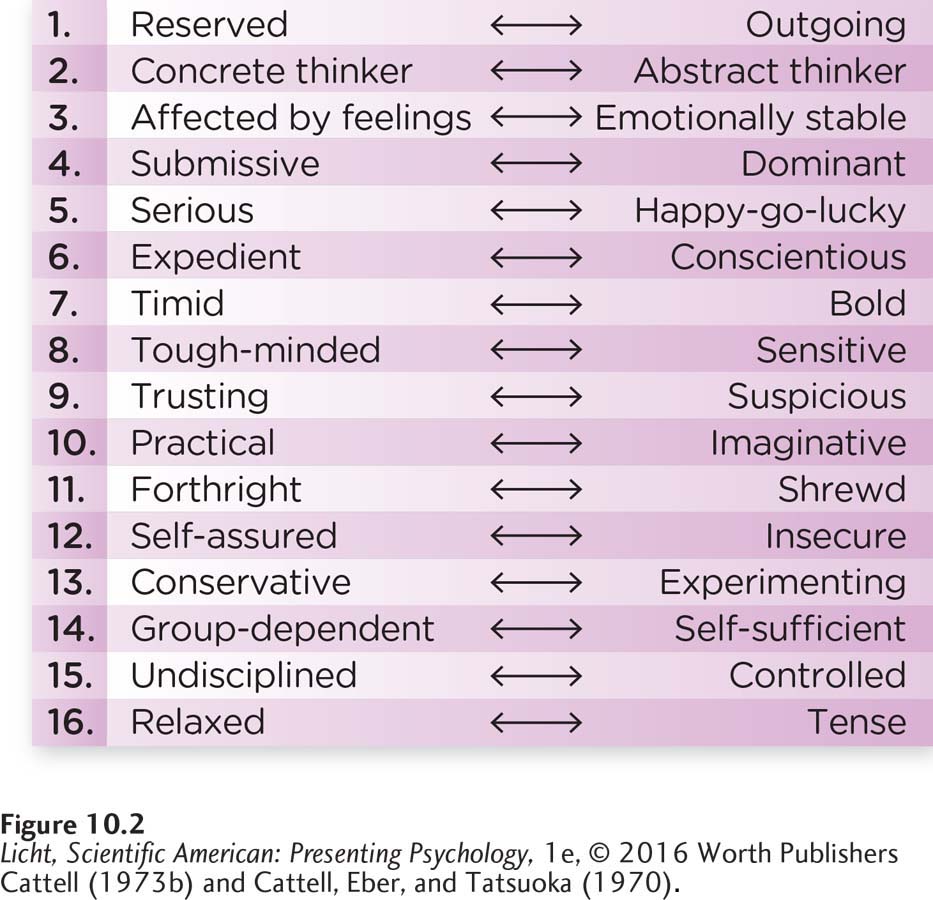

Cattell also condensed the list of surface traits into a much smaller set of 171. Realizing that some of these surface traits would be correlated, he used a statistical procedure known as factor analysis to group them into a smaller set of dimensions according to common underlying properties. With factor analysis, Cattell was able to produce a list of 16 personality factors.

These 16 factors, or personality dimensions, can be considered primary source traits. Looking at Figure 10.2, you can see that the ends of the dimensions represent polar extremes. On one end of the first dimension is the reserved and unsocial person; at the other end is the “social butterfly.” Based on these factors, Cattell developed the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (16PF), which is described in greater detail in the upcoming section on objective personality tests.

Using this list of 16 source traits, Raymond Cattell produced personality profiles by measuring where people fell between the two opposing ends of the dimension for each trait.

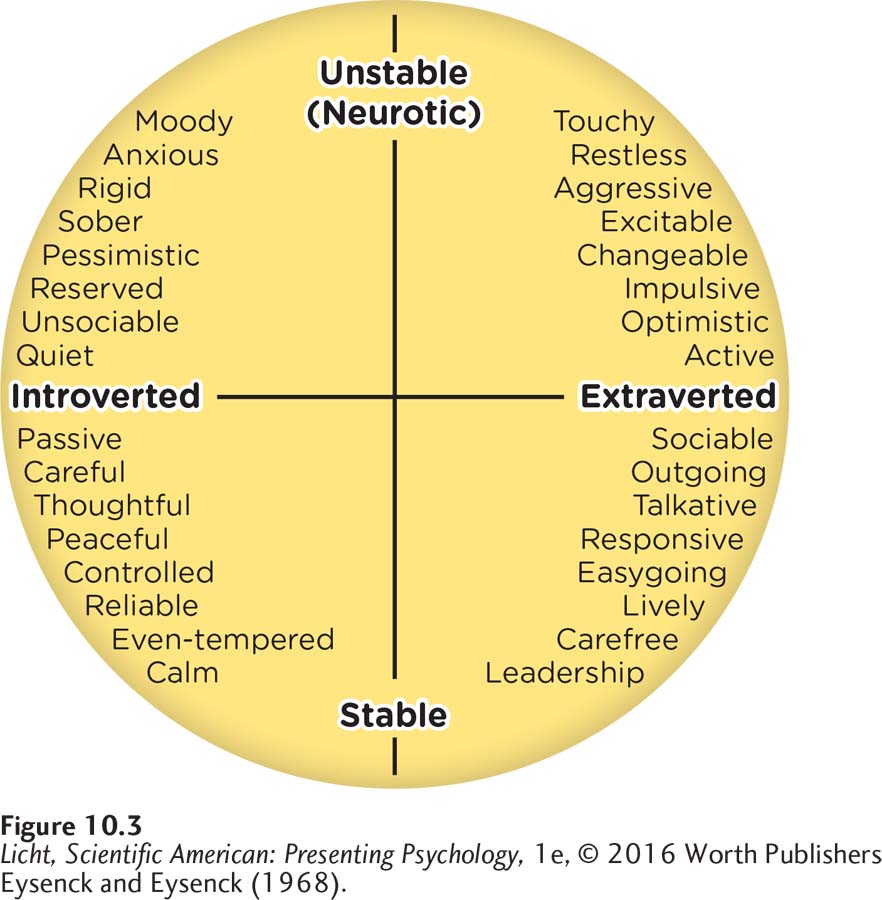

EYSENCK AND PERSONALITY Hans Eysenck (ahy-

Psychologist Hans Eysenck developed a model showing the range of human personality dimensions. This figure displays only the original dimensions Eysenck studied, but years later he proposed an additional dimension: psychoticism. People who score high on the psychoticism trait tend to be impersonal and antisocial.

426

People high on the extraversion end of the introversion–

In addition to identifying these dimensions, Eysenck worked diligently to unearth their biological basis. For example, he proposed a direct relationship between the behaviors associated with the introversion–

The trait theories of Allport, Cattell, and Eysenck paved the way for the trait theories commonly used today. Let’s take a look at one of the most popular models.

LO 12 Identify the biological roots of the five-

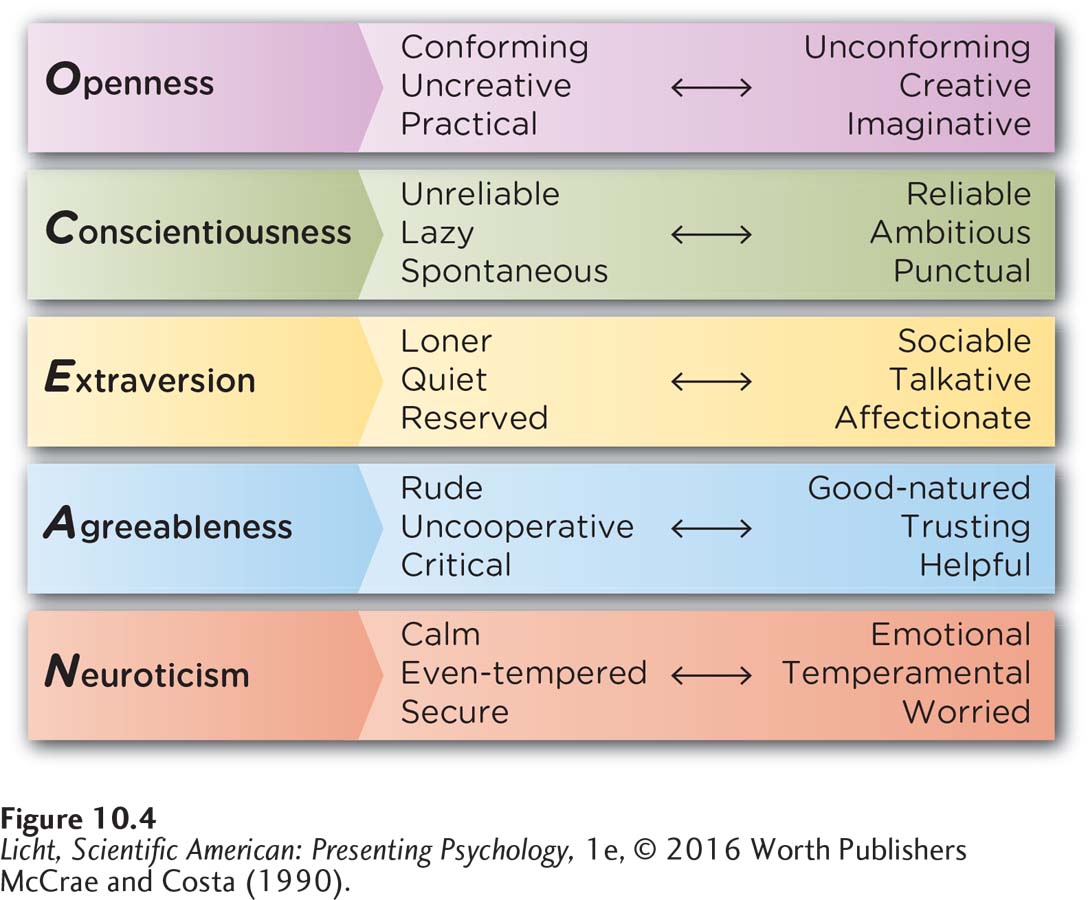

five-

The mnemonic OCEAN will help you remember these factors.

THE BIG FIVE The five-

Empirical support for this model has been established using cross-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we described the Minnesota twin studies, which showed that genes play a role in intellectual abilities. Identical twins share 100% of their genes, fraternal twins share about 50% of their genes, and adopted siblings are genetically very different. Comparing personality traits among these siblings can show the relative importance of genes (nature) and the environment (nurture).

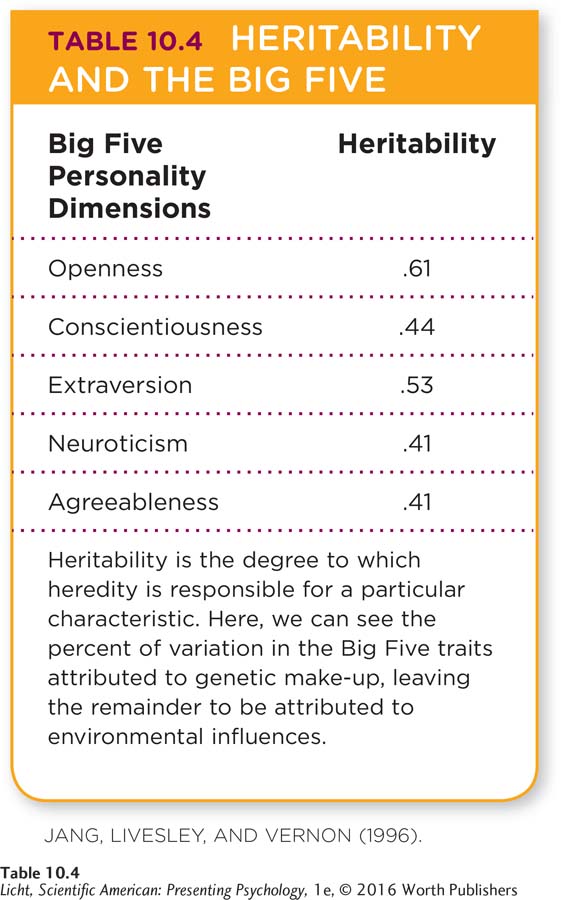

One possible explanation is that these five dimensions are biologically based and universal to humans (Allik & McCrae, 2004; McCrae et al., 2000). Three decades of twin and adoption studies point to a genetic basis for these five factors (McCrae et al., 2000; Yamagata et al., 2006), with openness to experience showing the greatest degree of heritability (McCrae et al., 2000; Table 10.4). Some researchers suggest that dog personalities can be described using similar dimensions, such as extraversion and neuroticism (Ley, Bennett, & Coleman, 2008). And such research is not limited to canines; animals as diverse as squid and orangutans seem to display personality characteristics that are surprisingly similar to those observed in humans (Sinn & Moltschaniwskyj, 2005; Weiss, King, & Perkins, 2006).

427

The biological basis of these five factors is further supported by their general stability over time (Kandler et al., 2010; McCrae et al., 2000). This implies that the dramatic environmental changes most of us experience in life do not have as great an impact as our inherited characteristics. That does not mean personalities are completely static, however; people can experience changes in these five factors over the life span (Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2011). For example, as people age, they tend to score higher on agreeableness and lower on neuroticism, openness, extraversion, and conscientiousness. They also seem to become happier and more easygoing with age, displaying more positive attitudes (Marsh, Nagengast, & Morin, 2013).

Apply This

Personality traits impact your life in ways you may find surprising. Would you believe that creativity—

Japanese calligrapher Kawamata-

Men and women appear to differ with respect to the five factors, although there is not total agreement on how. A review of studies from 55 nations reported that, across cultures, women score higher than men on conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism (Schmitt, Realo, Voracek, & Allik, 2008). Men, on the other hand, seem to demonstrate greater openness to experience. These disparities are not extreme, however; the variation within the groups of males and females is greater than the differences between males and females. Critics suggest that using such rough measures of personality may conceal some of the true differences between men and women; in order to shed light on such disparities, they suggest investigating models that incorporate 10 to 20 traits rather than just 5 (Del Giudice, Booth, & Irwing, 2012).

428

The five-

Maybe you could have predicted women would score higher on measures of agreeableness and neuroticism; perhaps you would have guessed the opposite. Research suggests that some gender stereotypes do indeed contain a kernel of truth (Costa, Terracciano, & McCrae, 2001; Terracciano et al., 2005). Let’s find out if this principle holds true for cultural stereotypes as well.

across the WORLD

Culture of Personality

Have you heard the old joke about European stereotypes? It starts out like this: In heaven, the chefs are French, the mechanics German, the lovers Italian, the police officers British, and the bankers Swiss (Mulvey, 2006, May 15). This joke plays upon what psychologists might call “national stereotypes,” or preconceived notions about the personalities of people belonging to certain cultures. The joke assumes, for example, that Italian people have some underlying quality that makes them excel in romance but not money management. Are such national stereotypes accurate?

Have you heard the old joke about European stereotypes? It starts out like this: In heaven, the chefs are French, the mechanics German, the lovers Italian, the police officers British, and the bankers Swiss (Mulvey, 2006, May 15). This joke plays upon what psychologists might call “national stereotypes,” or preconceived notions about the personalities of people belonging to certain cultures. The joke assumes, for example, that Italian people have some underlying quality that makes them excel in romance but not money management. Are such national stereotypes accurate?

PLEASE LEAVE YOUR STEREOTYPES AT THE BORDER!

To get to the bottom of this question, a group of researchers used personality tests to assess the Big Five traits of nearly 4,000 people from 49 cultures (Terracciano et al., 2005). When they compared the results of the personality tests to national stereotypes, they found no evidence that the stereotypes mirrored reality. Not only are these stereotypes invalid, but as history demonstrates, they can pave the way for “prejudice, discrimination, or persecution” (p. 99).

An Appraisal of the Trait Theories

As you can see from the examples above, trait theories have facilitated important psychological research. But like any scientific approach, they have their flaws. One major criticism is that trait theories fail to explain the origins of personality. What aspects of personality are innate, and which are environmental? How do unconscious processes, motivations, and development influence personality? If you’re looking to answer these types of questions, trait theories might not be your best bet.

Trait theories also tend to underestimate environmental influences on personality. As psychologist Walter Mischel pointed out, environmental circumstances can affect the way traits manifest themselves (Mischel & Shoda, 1995). A person who is high on the openness factor may be nonconforming in college, wearing unique clothing and pursuing unusual hobbies, but put her in the military and her nonconformity will probably assume a new form.

show what you know

429

Question 1

1. ____________ was a humanist who was interested in exploring people who are self-

Abraham Maslow; Carl Rogers

Question 2

2. The total acceptance of a child regardless of her behavior is known as:

conditions of worth.

repression.

the real self.

unconditional positive regard.

d. unconditional positive regard.

Question 3

3. According to ____________, personality is the compilation of behaviors that have been shaped via reinforcement and other forms of conditioning.

learning theory

Question 4

4. Julian Rotter proposed that personality is influenced by ____________, one’s beliefs about where responsibility or control exists.

reinforcement

locus of control

expectancy

reinforcement value

b. locus of control

Question 5

5. Reciprocal determinism represents a complex multidirectional interaction among beliefs, behavior, and environment. Draw a diagram illustrating how reciprocal determinism explains one of your behavior patterns.

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following definition (and see Infographic 10.2). Reciprocal determinism refers to the multidirectional interactions among cognitions, behaviors, and the environment guiding our behavior patterns and personality.

Question 6

6. The relatively stable properties of personality are:

traits.

expectancies.

reinforcement values.

ego defense mechanisms.

a. traits.

Question 7

7. Name the Big Five traits and give one piece of evidence for their biological basis.

Answers will vary (and see Table 10.4). The Big Five traits include openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Three decades of twin and adoption studies point to a genetic (and therefore biological) basis of these five factors. The proportion of variation in the Big Five traits attributed to genetic make-