12.3 From Depression to Mania

MELISSA’S SECOND DIAGNOSIS Unfortunately for Melissa, receiving a diagnosis and treatment did not solve her problems. She hated herself for having OCD, and her parents and some friends had a hard time accepting her diagnosis. “Every day I woke up, I wanted to die,” says Melissa, who reached a breaking point during her sophomore year in high school. After a particularly difficult day at school, Melissa returned home with the intention of taking her own life. Luckily, a friend recognized that she was in distress and notified Melissa’s family members, who rushed home to find Melissa curled up in a ball in the corner of her room, rocking back and forth and mumbling nonsense. They took Melissa to the hospital, where she would be safe and begin treatment. During her 3-

MELISSA’S SECOND DIAGNOSIS Unfortunately for Melissa, receiving a diagnosis and treatment did not solve her problems. She hated herself for having OCD, and her parents and some friends had a hard time accepting her diagnosis. “Every day I woke up, I wanted to die,” says Melissa, who reached a breaking point during her sophomore year in high school. After a particularly difficult day at school, Melissa returned home with the intention of taking her own life. Luckily, a friend recognized that she was in distress and notified Melissa’s family members, who rushed home to find Melissa curled up in a ball in the corner of her room, rocking back and forth and mumbling nonsense. They took Melissa to the hospital, where she would be safe and begin treatment. During her 3-

Melissa (right) poses with childhood friend Mary Beth, whom she credits for helping save her life. The day that Melissa came home intending to attempt suicide, Mary Beth recognized her friend’s distress and called for help. Thanks to the intervention of friends and family, Melissa received the treatment she needed.

DSM–

LO 6 Summarize the symptoms and causes of major depressive disorder.

major depressive disorder A psychological disorder that includes at least one major depressive episode, with symptoms such as depressed mood, problems with sleep, and loss of energy.

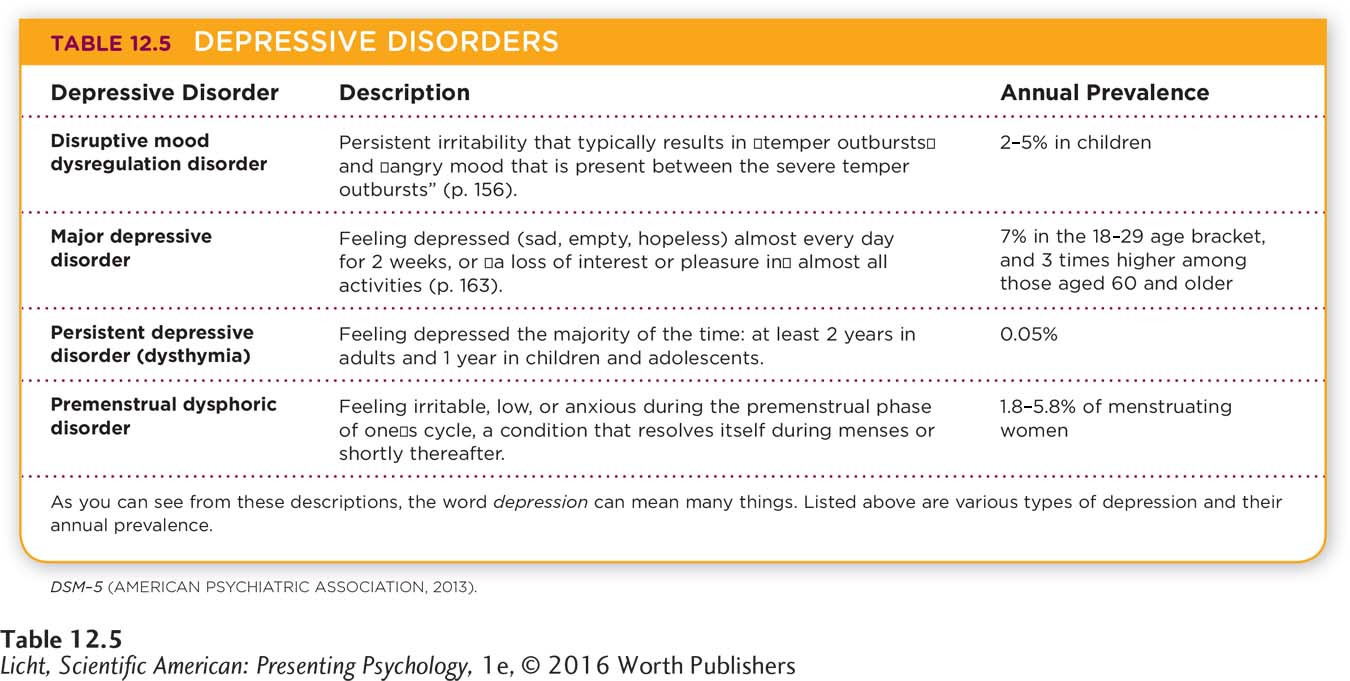

During that hospital stay, doctors gave Melissa a new diagnosis in addition to OCD. They told her that she was suffering from depression. Apparently, the profound sadness and helplessness she had been feeling were symptoms of major depressive disorder, one of the depressive disorders described in the DSM–

depressed mood, which might result in feeling sad or hopeless;

reduced pleasure in activities almost all of the time;

substantial loss or gain in weight, without conscious effort, or changes in appetite;

sleeping excessively or not sleeping enough;

feeling tired, drained of energy;

feeling worthless or extremely guilt-

ridden; difficulty thinking or concentrating;

persistent thoughts about death or suicide.

Actor Jon Hamm is among the millions of Americans who have struggled with depression (Vernon, 2010, September 18). In any one year, approximately 7% of the American population is diagnosed with major depressive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Kessler, Chiu, et al., 2005). If you or someone you know appears to be experiencing depression or suicidal thoughts, do not hesitate to seek help. Call the National Suicide Prevention Line: 1-

493

Someone with five or more of these symptoms would feel significantly distressed and experience problems in social interactions and at work.

In order to be diagnosed with major depressive disorder, a person must have experienced at least one major depressive episode. Some people suffer a single episode, while others battle recurrent episodes. In some instances, the disorder is triggered by the birth of a baby. Approximately 3–

When making a diagnosis, the clinician must be able to distinguish the symptoms of major depression from normal reactions to a “significant loss,” such as the death of a loved one. This is not always easy because responses to death often resemble depression. A key distinction is that grief generally decreases with time, and comes in waves associated with memories or reminders of the loss; the sadness associated with a major depressive episode tends to remain steady (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Major depressive disorder is one of the most common and devastating psychological disorders. In the United States, for example, the lifetime prevalence of major depressive disorder is almost 17% (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005); this means that nearly 1 in 5 people experience a major depressive episode at least once in life. Women are more likely to be affected than men (Kessler et al., 2003), and rates of this disorder are already 1.5 to 3 times higher for females beginning in adolescence (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The effects of major depressive disorder extend far beyond the individual. For Americans ages 15 to 44, this condition is at the top of the list enumerating causes of disability (World Health Organization, 2008a)—and this means it impacts the productivity of the workforce. In a comprehensive study of major depressive disorder, respondents reported that their symptoms prevented them from going to work or performing day-

494

CULTURE Depression is one of the most common disorders in the world, yet the symptoms experienced, the course of treatment, and the words used to describe it vary from culture to culture. For example, people in China rarely report feeling “sad,” but instead focus on physical symptoms, such as dizziness, fatigue, or inner pressure (Kleinman, 2004). In Thailand, depression is commonly expressed through physical and mental symptoms, such as headaches, fatigue, daydreaming, social withdrawal, irritation, and forgetfulness (Chirawatkul, Prakhaw, & Chomnirat, 2011).

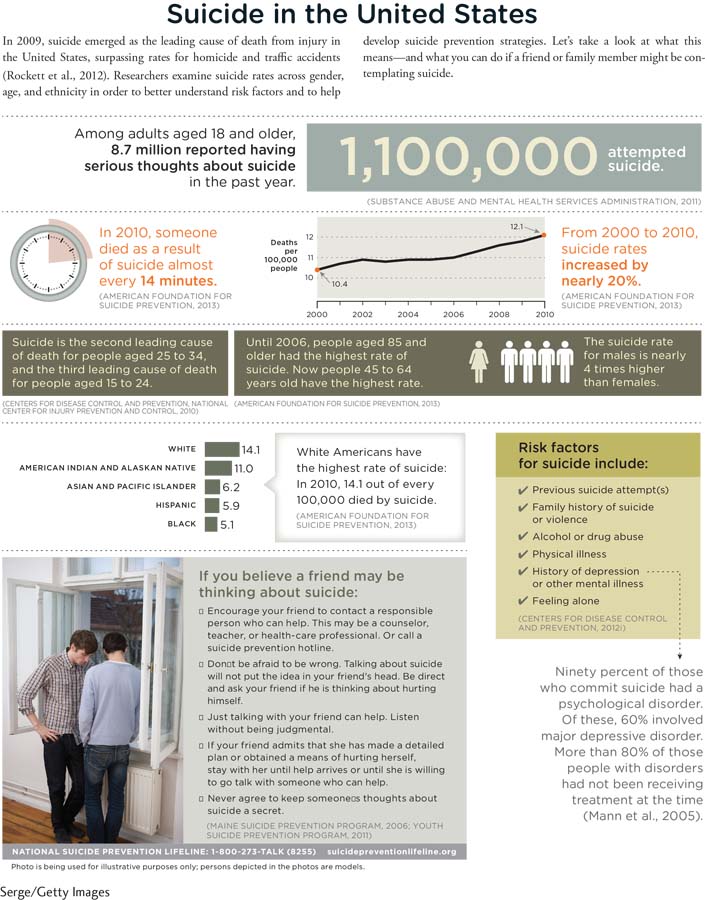

SUICIDE The recurrent nature of major depressive disorder creates increased risk for suicide and health complications (Monroe & Harkness, 2011). Around 9% of adults in 21 countries confirm they have harbored “serious thoughts of suicide” at least once (Infographic 12.2), and around 3% have attempted suicide (Borges et al., 2010). According to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, 2013, October 1), approximately 90% of people who commit suicide have a psychological disorder, usually depressive disorder and/or substance abuse disorder.

495

INFOGRAPHIC 12.2

The Biology of Depression

Nearly 7% of Americans battle depression in any given year (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Kessler, Chiu, et al., 2005). What underlies this staggering statistic? There appears to be something biological at work.

GENETIC FACTORS Studies of twins, family pedigrees, and adoptions tell us that major depressive disorder runs in families, with a heritability rate of approximately 40–

NEUROTRANSMITTERS AND THE BRAIN Three neurotransmitters appear to be associated with the cause and course of major depressive disorder: norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine. The relationships among these neurotransmitters are complicated and research is still ongoing (El Mansari et al., 2010; Torrente, Gelenberg, & Vrana, 2012), but the findings are intriguing. For example, serotonin deficiency has been associated with major depressive disorder (Torrente et al., 2012), and genes may be responsible for some of this irregular activity, particularly in the amygdala and other brain areas involved in processing emotions associated with this disorder (Northoff, 2012).?Depression also seems to be correlated with specific structural features in the brain (Andrus et al., 2012). People with major depressive disorder may have irregularities in the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus. For example, some regions of the right cortex show significant thinning in people who face a high risk of developing major depressive disorder (Peterson et al., 2009). Studies have zeroed in on a variety of factors, such as increased structure size, decreased volume, and changes in neural activity (Kempton et al., 2011; Sacher et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2013). Research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technologies points to irregularities in neural pathways involved in processing emotions and rewards for people with major depressive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Major depressive disorder most likely results from a complex interplay of many neural factors. What’s difficult to determine is whether changes in the brain precede the disorder, or the disorder alters the brain.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described the endocrine system, which uses glands to convey messages via hormones. These chemicals released into the bloodstream can cause aggression and mood swings, as well as influence growth and alertness. Hormones may also play a role in major depressive disorder.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 11, we discussed the HPA system, which helps to maintain balance in the body by overseeing the sympathetic nervous system, the neuroendocrine system, and the immune system. The HPA system is also associated with depressive episodes.

HORMONES There is also evidence that hormones play a role in depression. People with depressive disorders may have high levels of cortisol, a hormone secreted by the adrenal glands (Belmaker & Agam, 2008; Dougherty, Klein, Olino, Dyson, & Rose, 2009). Women sufferers, in particular, appear to be affected by stress-

Psychological Roots of Depression

Having a baby is a stressful, life-

496

Earlier we mentioned heritability rates of 40–

learned helplessness A tendency for people to believe they have no control over the consequences of their behaviors, resulting in passive behavior.

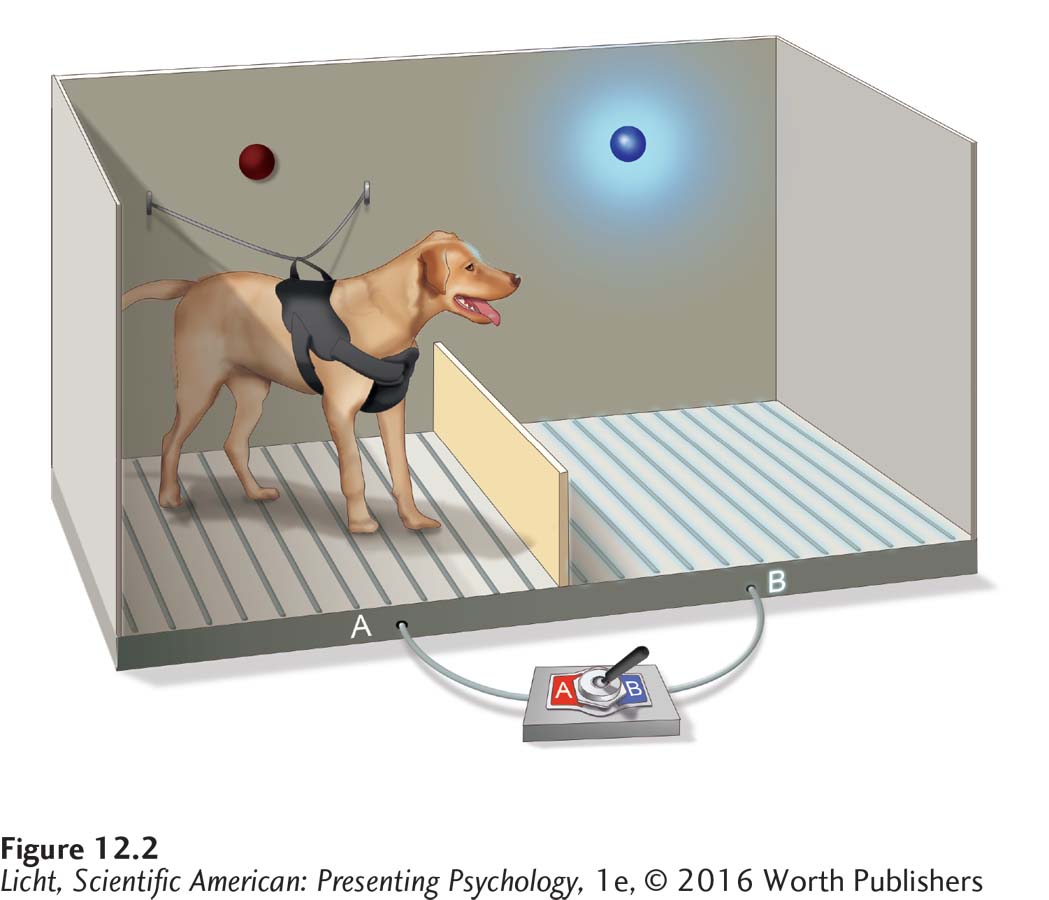

LEARNED HELPLESSNESS According to researcher Martin Seligman, people often become depressed because they believe they have no control over the consequences of their behaviors (Overmier & Seligman, 1967; Seligman, 1975; Seligman & Maier, 1967). To demonstrate this learned helplessness, Seligman restrained dogs in a “hammock” and then randomly administered inescapable painful electric shocks to their paws (Figure 12.2). The next day the same dogs were put into another cage. Although unrestrained, they did not try to escape shocks administered through a floor grid (even though they could have, by jumping over a low barrier in the cage). Seligman concluded the dogs had learned they couldn’t control painful experiences during the prior training; they were acting in a depressed manner. He translated this finding to people with major depressive disorder, suggesting that they too feel powerless to change things for the better, and therefore become depressed.

Dogs restrained in a hammock were unable to escape painful shocks administered through an electrical grid on the floor of a specially designed cage called a shuttle box. The dogs soon learned that they were helpless and couldn’t control these painful experiences. They did not try to escape by jumping over the barrier even when they were not restrained. The figure here shows the electrical grid activated on side B.

NEGATIVE THINKING Cognitive therapist Aaron Beck (1976) suggested that depression is connected with negative thinking. Depression, according to Beck, is the product of a “cognitive triad”—a negative view of experiences, self, and the future. Here’s an example: A student receives a failing grade on an exam, so she begins to think she is a poor student, and that belief leads her to the conclusion that she will fail the course. This self-

497

If you aren’t convinced that beliefs contribute to depression, consider this: The way people respond to their experience of depression may impact the severity of the disorder. People who repeatedly focus on this experience are much more likely to remain depressed and perhaps even descend into deeper depression (Eaton et al., 2012; Nolen-

We can think of mental health as a continuum, with healthy thoughts, emotions, and behaviors at one extreme, and dysfunction, distress, and deviance at the other. We can also conceptualize mood as a continuum, with a depressed mood at one end and neutral moods (not too sad, not too happy) in the center. But what lies at the other extreme? If it’s the opposite of depression, then it must be good, right? Not necessarily, as you will soon see.

Bipolar Disorders

HIGHEST HIGHS, LOWEST LOWS When Ross began battling bipolar disorder, he went through periods of euphoria and excitement. Sometimes he would stay awake for 4 consecutive days, or sleep barely an hour per night for 2 weeks in a row—

HIGHEST HIGHS, LOWEST LOWS When Ross began battling bipolar disorder, he went through periods of euphoria and excitement. Sometimes he would stay awake for 4 consecutive days, or sleep barely an hour per night for 2 weeks in a row—

DSM–

LO 7 Compare and contrast bipolar disorders and major depressive disorder.

manic episodes States of continuous elation that is out of proportion to the setting, and can include irritability, very high and sustained levels of energy, and an “expansive” mood.

The extreme energy, euphoria, and confidence Ross felt were most likely the result of manic episodes, also known as mania. Manic episodes are often characterized by continuous elation that is out of proportion for the situation. Other features include irritability, very high and sustained levels of energy, and an “expansive” mood, meaning the person feels more powerful than he really is and behaves in a showy or overly confident way. During one of these manic episodes, a person exhibits three or more of the symptoms listed below, which represent deviations from normal behavior (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

grandiose or extremely high self-

esteem; reduced sleep;

increased talkativeness;

a “flight of ideas” or the feeling of “racing” thoughts;

easily distracted;

heightened activity at school or work;

physical agitation;

displaying poor judgment and engaging in activities that could have serious consequences (risky sexual behavior, or excessive shopping sprees, for example).

498

It is not unusual for a person experiencing a severe manic episode to be hospitalized. Mania is difficult to hide and can be dangerous. One may act out of character, doing things that damage important relationships or jeopardize work. A person may become violent, posing a risk to himself and others. Seeking help is unlikely, because mania leads to impaired judgment, feelings of grandiosity, and euphoria. (Why would you seek help if you feel on top of the world?) At these times, the support of others is essential.

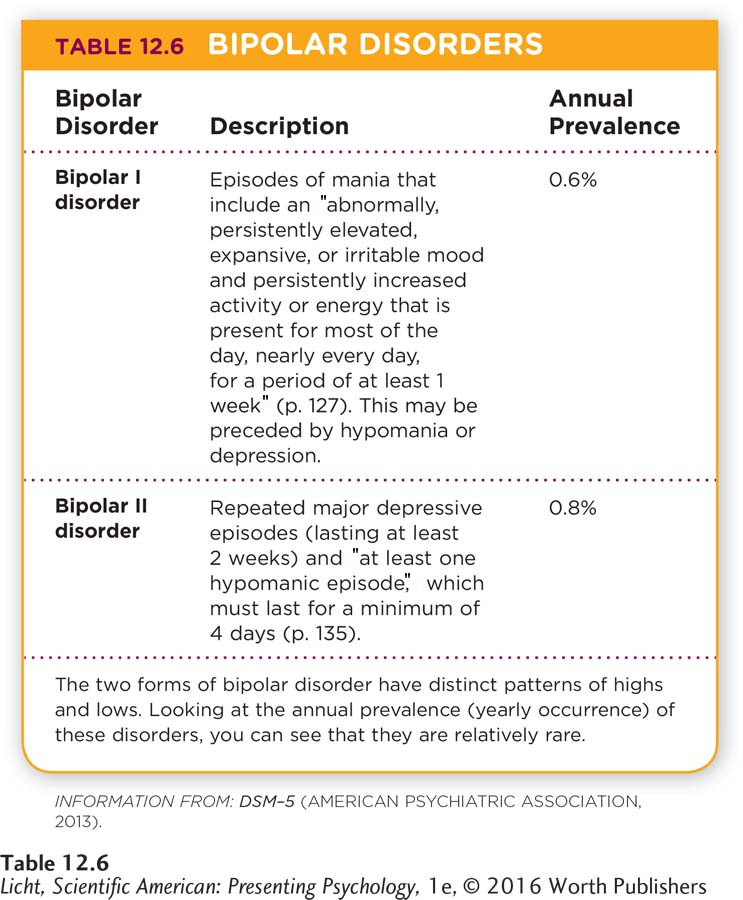

There are various types of bipolar disorder. To be diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, a person must experience at least one manic episode, substantial distress, and great impairment. Bipolar II disorder requires at least one major depressive episode as well as a hypomanic episode. Hypomania is associated with some of the same symptoms as a manic episode, but it is not as severe and does not impair one’s ability to function (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Table 12.6).

BIPOLAR CYCLING Some people with bipolar disorder cycle between extreme highs and lows of emotion and energy that last for days, weeks, or even months. During bouts of mania, a person’s mood can be unusually elevated, irritable, or expansive. At the other extreme are feelings of deep sadness, emptiness, and helplessness. Periods of mania and depression may be brought on by life changes and stressors (Malkoff-

Actress Catherine Zeta-

Bipolar disorder is uncommon. Over the course of a lifetime, about 0.8% of the American population will receive a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder, and 1.1% bipolar II disorder (Merikangas et al., 2007). Men and women are equally likely to be affected, but men tend to experience earlier onset of symptoms, while the incidence for women seems to be higher later in life (Altshuler et al., 2010; Kennedy et al., 2005).

WHO GETS BIPOLAR DISORDER? Although researchers have not determined the cause of bipolar disorder, evidence from twin and adoption studies underscores the importance of genes. If one identical twin is diagnosed with bipolar disorder, there is a 40–

But nature is not the only force at work in bipolar disorder; nurture seems to play an important role, too. The fact that there is a higher rate of bipolar disorder in high-

499

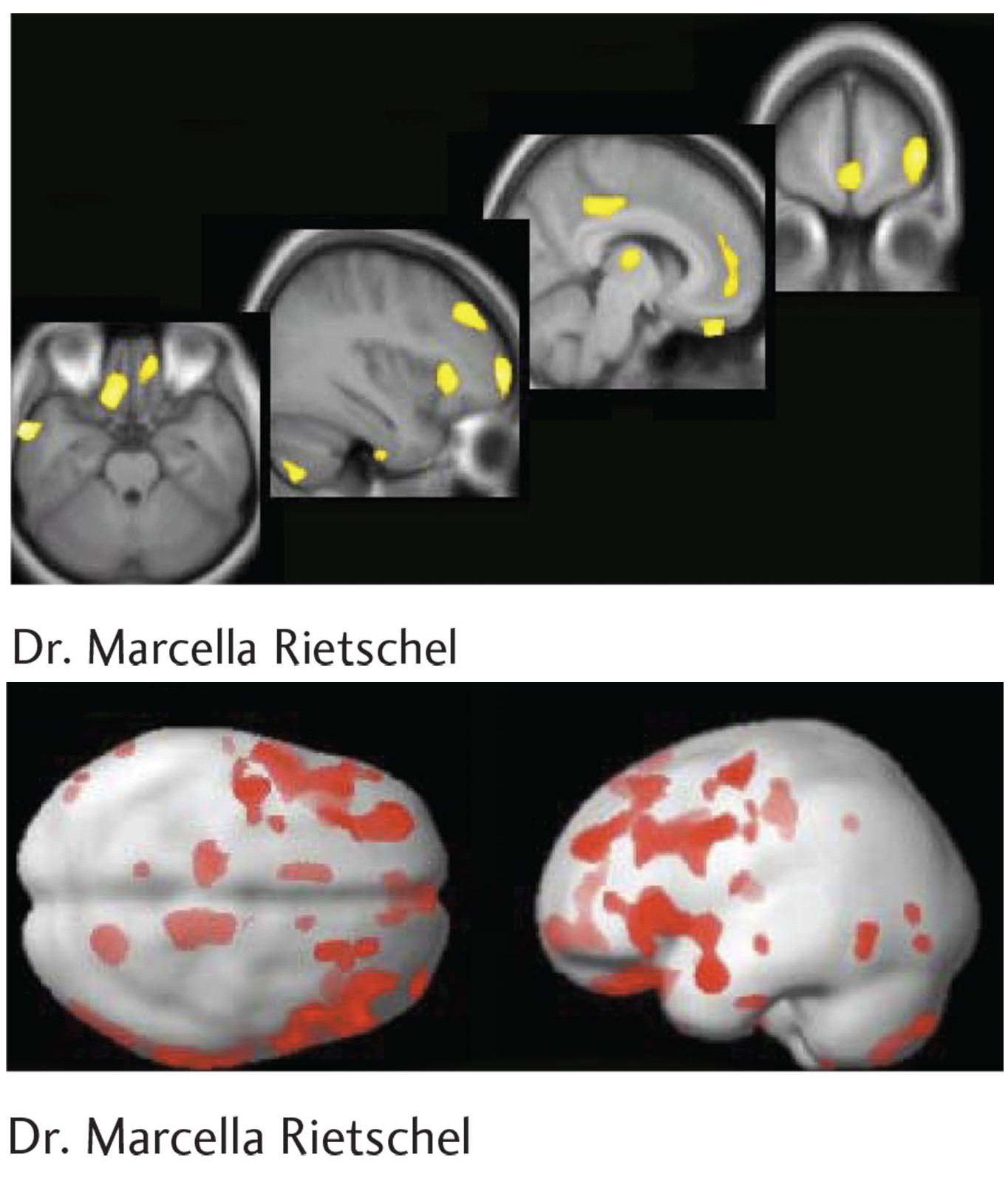

Using imaging techniques, researchers have identified certain brain irregularities that appear to be linked to bipolar disorder. These MRI images highlight areas of decreased gray matter volume in prefrontal and temporal areas associated with high-

show what you know

Question 1

1. There are many factors involved in the cause and course of major depressive disorder. Prepare notes for a 5-

Answers will vary, but can be based on the following information. The symptoms of major depressive disorder can include feelings of sadness or hopelessness, reduced pleasure, sleeping excessively or not at all, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness, or difficulties thinking or concentrating. The hallmarks of major depressive disorder are the “substantial” severity of symptoms and impairment in the ability to perform expected roles. Biological theories suggest the disorder results from a genetic predisposition, neurotransmitters, and hormones. Psychological theories suggest that feelings of learned helplessness and negative thinking may play a role. Not just one factor is involved in major depressive disorder, but rather the interplay of several.

Question 2

2. Ross described going 4 days without sleeping, or 2 weeks sleeping only 1 hour per night. He was exploding with energy, and feeling on top of the world. It is likely that Ross was experiencing periods of euphoria and excitement known as:

depression.

manic episodes.

panic attacks.

anxiety.

b. manic episodes.

Question 3

3. What is the difference between bipolar I disorder and bipolar II disorder?

In order to be diagnosed with bipolar I disorder, a person must experience at least one manic episode spanning a week or more. These periods of mania are characterized by increased energy and activity and unusual excitement and/or irritability. Depression and hypomania may also occur.

To be diagnosed with bipolar II disorder, a person must experience recurrent episodes of major depression lasting 2 or more weeks and at least one episode of hypomania spanning 4 or more days. Hypomania is a mild version of mania; the symptoms are similar, but not disabling.

Question 4

4. Compare the symptoms of bipolar disorder with those of major depressive disorder.

A diagnosis of bipolar I disorder requires that a person experience at least one manic episode, substantial distress, and great impairment. Bipolar II disorder requires at least one major depressive episode as well as a hypomanic episode, which is associated with some of the same symptoms as a manic episode, but is not as severe and does not impair one’s ability to function. People with bipolar disorder cycle between extreme highs and lows of emotion and energy that last for days, weeks, or even months. Individuals with major depressive disorder, on the other hand, tend to experience a persistent low mood, loss of energy, and feelings of worthlessness.