13.2 Insight Therapies

521

Laura Lichti had many reasons to feel proud the day she received her master’s degree in counseling. After working full-

AWARENESS EQUALS POWER Laura Lichti grew up in a picturesque town high in the clouds of the Rocky Mountains. Her family was, in her words, “very, very conservative,” and her church community tight-

AWARENESS EQUALS POWER Laura Lichti grew up in a picturesque town high in the clouds of the Rocky Mountains. Her family was, in her words, “very, very conservative,” and her church community tight-

With her gentle line of inquiry, the mentor encouraged Laura to search within herself for answers. Thoughtfully, empathically, she taught Laura how to find her voice, create her own solutions, and direct her life in a way that was true to herself. “[She] took it back to me,” Laura says. “It was beautiful.”

Inspired to give others what her mentor had given her, Laura resolved to become a psychotherapist for children and teens. She paid her way through community college, went on to a 4-

Today, Laura empowers clients much in the same way her mentor empowered her—

Taking It to the Couch, Freudian Style: Psychoanalysis

LO 3 Describe how psychoanalysis differs from psychodynamic therapy.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 10, we introduced the concept of repression, which is a defense mechanism through which the ego moves anxiety-

When imagining the stereotypical “therapy” session, many people picture a person reclining on a couch and talking about dreams and memories from childhood. Modern-

FREUD AND THE UNCONSCIOUS Sigmund Freud (1900/1953), the father of psychoanalysis, proposed that humans are motivated by two animal-

523

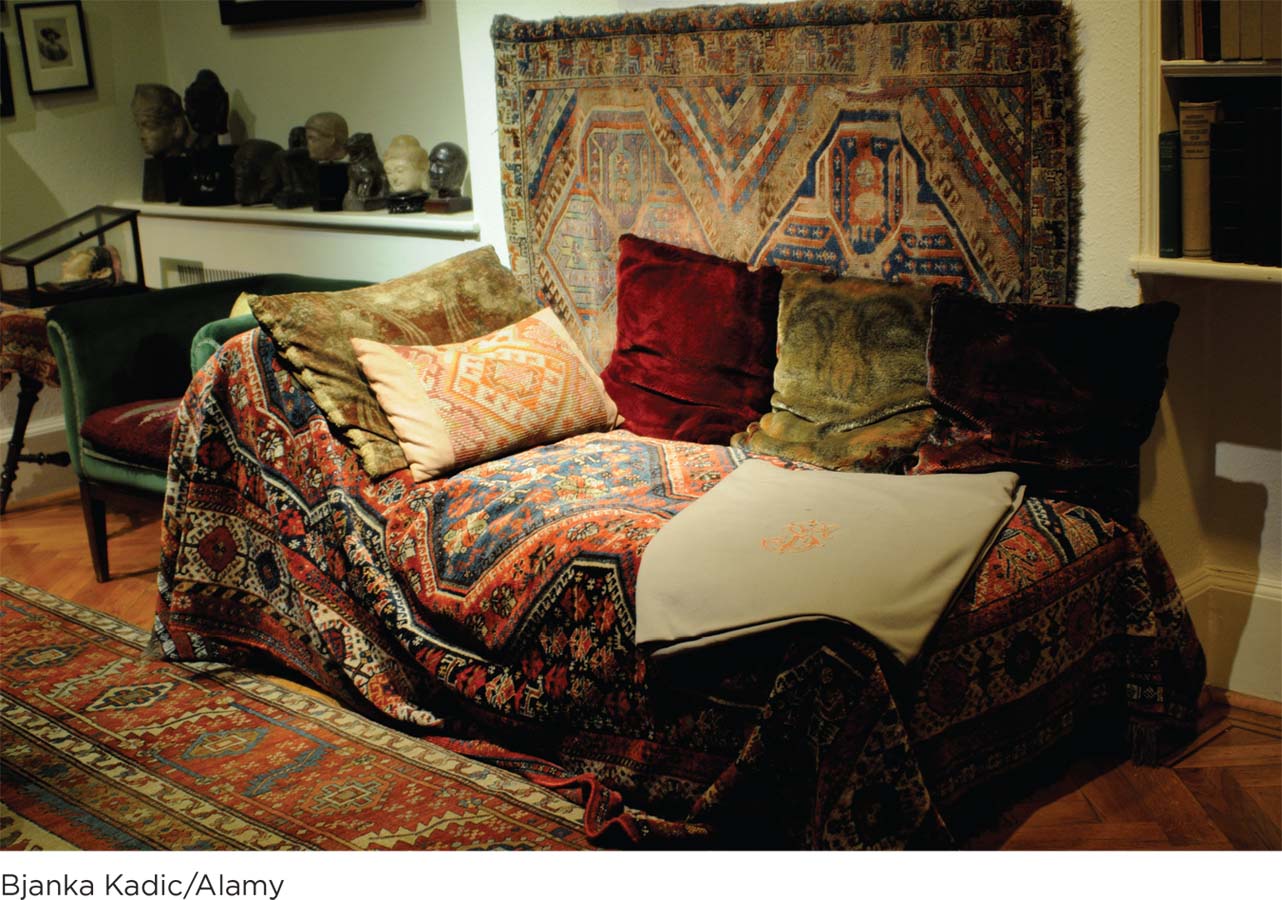

Freud’s psychoanalytic couch appears on display at the Freud Museum in London. All of Freud’s patients reclined on this piece of furniture, which is reportedly quite comfortable with its soft cushions and Iranian rug cover (Freud Museum, n.d., para. 4). Freud sat in the chair at the head of the couch, close to but not within view of his patient. Bjanka Kadic/Alamy

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 4, we introduced Freud’s theory of dreams. He suggested manifest content is the apparent meaning of a dream. The latent content contains the hidden meaning of a dream, representing unconscious urges. Freud believed that to expose this latent content, we must look deeper than the reported storyline of the dream.

free association A psychoanalytic technique in which a patient says anything that comes to mind.

Dreams, according to Freud, are a pathway to unconscious thoughts and desires (Freud, 1900/1953). The overt material of a dream (what we remember upon waking) is called its manifest content, which can disguise a deeper meaning, or latent content, hidden from awareness due to potentially uncomfortable issues and desires. Freud would often use dreams as a launching pad for free association, a therapy technique in which a patient says anything and everything that comes to mind, regardless of how silly, bizarre, or inappropriate it may seem.

interpretation A psychoanalytic technique used to discover unconscious conflicts driving behavior.

Freud believed this seemingly directionless train of thought would lead to clues about the patient’s unconscious. Piecing together the hints he gathered from dreams, free association, and other parts of therapy sessions, Freud would identify and make inferences about the unconscious conflicts driving the patient’s behavior. He called this investigative work interpretation. When the time seemed right, Freud would share his interpretations, increasing the patient’s self-

resistance A patient’s unwillingness to cooperate in therapy; a sign of unconscious conflict.

You might be wondering what behaviors psychoanalysts consider signs of unconscious conflict. One indicator is resistance, a patient’s unwillingness to cooperate in therapy. Examples of resistance might include “forgetting” appointments or arriving late for them, or becoming angry or agitated when certain topics arise. Resistance is a crucial step in psychoanalysis because it means the discussion might be veering close to something that makes the patient feel uncomfortable and threatened, like a critical memory or conflict causing distress. If resistance occurs, the job of the therapist is to help the patient identify its unconscious roots.

transference A type of resistance that occurs when a patient reacts to a therapist as if dealing with parents or other caregivers from childhood.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 10, we presented projective personality tests. The assumption is that the test taker’s unconscious conflicts are projected onto the test material. It is up to the therapist to try to uncover these underlying issues. Here, the patient is projecting these conflicts onto a therapist.

Another key sign of unconscious conflict is transference, which occurs when a patient reacts to the therapist as if she is dealing with her parents or other important people from childhood. Suppose Chepa relates to Dr. Foster as if he were a favorite uncle. She never liked letting her uncle down, so she resists telling Dr. Foster things she suspects would disappoint him. Transference is a good thing, because it illuminates the unconscious conflicts fueling a patient’s behaviors (Hoffman, 2009). One of the reasons Freud sat off to the side and out of a patient’s line of vision was to encourage transference. With Freud in this neutral position, patients would have an easier time projecting their unconscious conflicts and feelings onto him.

TAKING STOCK: AN APPRAISAL OF PSYCHOANALYSIS The oldest form of talk therapy, psychoanalysis, is still alive and well today. But Freud’s theories have come under sharp criticism. For one thing, they are not evidence-

524

Although Freud’s theories have been criticized, the impact of his work is extensive (just note how often it is cited in this textbook). Freud helped us appreciate how childhood experiences and unconscious processes can shape personality and behavior. Even Laura, who does not identify herself as a psychoanalyst, says that Freudian notions sometimes come into play with her clients. If a person has a traumatic experience in childhood, for example, it may resurface both in therapy and real life, she notes. Like Laura, many contemporary psychologists do not identify themselves as psychoanalysts. But that doesn’t mean Freud has left the picture. Far from it.

Goodbye, Couch; Hello, Chairs: Psychodynamic Therapy

psychodynamic therapy A type of insight therapy that incorporates core psychoanalytic themes, including the importance of unconscious conflicts and experiences from the past.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 10, we introduced the neo-

Psychodynamic therapy is an updated take on psychoanalysis. This newer approach has been evolving over the last 30 to 40 years, incorporating many of Freud’s core themes, including the idea that personality and behaviors often can be traced to unconscious conflicts and experiences from the past.

However, psychodynamic therapy breaks from traditional psychoanalysis in important ways. Therapists tend to see clients once a week for several months rather than many times a week for years. And instead of sitting quietly off to the side of a client reclining on a couch, the therapist sits face-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we described the experimental method, a research technique that can uncover cause-

For many years, psychodynamic therapists treated clients without much evidence to back up their approach (Levy & Ablon, 2010, February 23). But recently, researchers have begun testing the effects of psychodynamic therapy with rigorous scientific methods, and their results are encouraging. Randomized controlled trials suggest psychodynamic psychotherapy is effective for treating an array of disorders, including depression, panic disorder, and eating disorders (Leichsenring & Rabung, 2008; Milrod et al., 2007; Shedler, 2010), and the benefits may last long after treatment has ended. People with borderline personality disorder, for example, appear to experience fewer and less severe symptoms (such as a reduction in suicide attempts) for several years following psychodynamic therapy (Bateman & Fonagy, 2008; Shedler, 2010). Yet, this approach is not ideal for everyone. It requires high levels of verbal expression and awareness of self and the environment. Symptoms like hallucinations or delusions might interfere with these requirements.

You Can Do It! Humanistic Therapy

LO 4 Outline the principles and characteristics of humanistic therapy.

For the first half of the 20th century, most psychotherapists leaned on the theoretical framework established by Freud. But in the 1950s, some psychologists began to question Freud’s dark view of human nature and his approach to treating clients. A new perspective began to take shape, one that focused on the positive aspects of human nature; this humanism would have a powerful influence on generations of psychologists, including Laura Lichti.

525

Thirteen-

THE CLIENT KNOWS During college, Laura worked as an adult supervisor at a residential treatment facility for children and teens struggling with mental health issues. The experience was eye-

THE CLIENT KNOWS During college, Laura worked as an adult supervisor at a residential treatment facility for children and teens struggling with mental health issues. The experience was eye-

Laura continues to use this approach in her work as a therapist, allowing each client to steer the course of his therapy. For example, Laura might begin a session by asking a client to experiment with art therapy. Some people are enthusiastic about art therapy; others resist, but Laura makes it a rule never to coerce a client with statements such as, “Well, you need to do it because I am your therapist.” Instead, she might say, “Okay, what do you think would work? If art is not going to work, what is interesting to you?” Maybe the client likes writing song lyrics; if so, Laura will follow his lead. “Okay, then why don’t you write a song for me?”

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced the field of positive psychology, which draws attention to human strengths and potential for growth. The humanistic perspective was a forerunner to this approach. As a treatment method, humanistic therapy emphasizes the positive nature of humans and strives to harness this for clients in treatment.

This approach to therapy is very much a part of the humanistic movement, which was championed by American psychotherapist Carl Rogers (1902–

humanistic therapy A type of insight therapy that emphasizes the positive nature of humankind.

With this optimistic spirit, Rogers and others pioneered several types of insight therapy collectively known as humanistic therapy, which emphasizes the positive nature of humankind. Unlike psychoanalysis, which tends to focus on the distant past, humanistic therapy concentrates on the present, seeking to identify and address current problems. And rather than digging up unconscious thoughts and feelings, humanistic therapy emphasizes the conscious experience: What’s going on in your mind right now?

LO 5 Describe person-

Synonyms

person-

person-

PERSON-

nondirective A technique used in person-

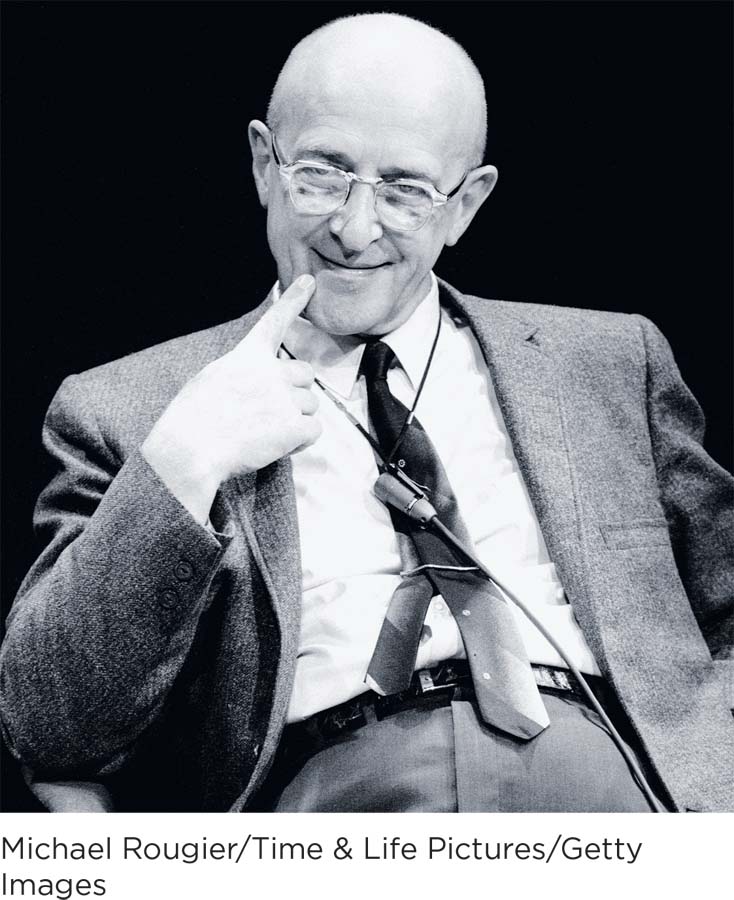

Carl Rogers leads a group therapy session in 1966. One of the founders of humanistic psychology, Rogers firmly believed that every human being is fundamentally good and capable of self-

Suppose Laura has a male client who is drawn toward artistic endeavors. He loves dancing, singing, and acting, but his parents believe that boys should be tough and play sports. The client has spent his life trying to become the person others expect him to be, meanwhile denying the person he is deep down, which leaves him feeling unfulfilled and empty. Using a person-

526

Part of Rogers’ philosophy was his refusal to identify the people he worked with as “patients” (Rogers, 1951). Patients depend on doctors to make decisions for them, or at least give them instructions. In Rogers’ mind, it was the patient who had the answers, not the therapist. So he began using the term client and eventually settled on the term person.

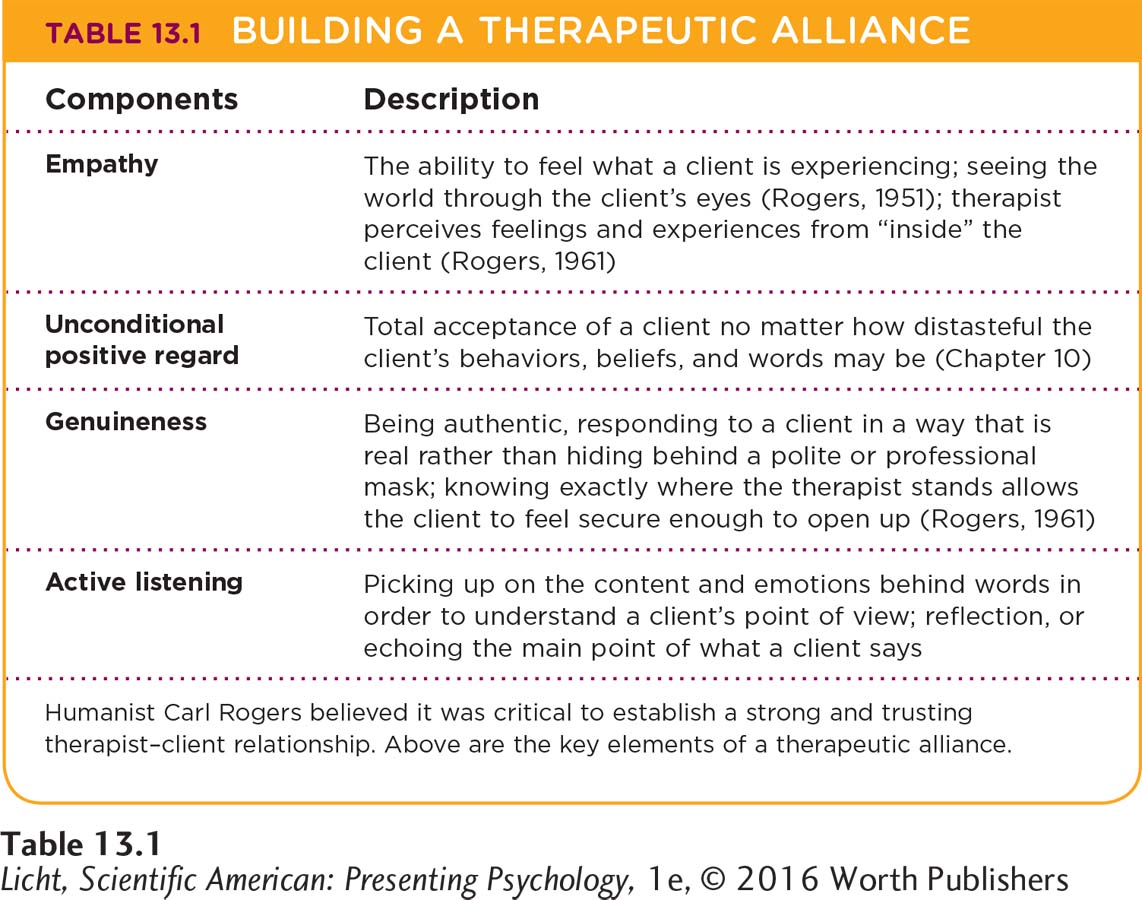

therapeutic alliance A warm and accepting client–

The focus in person-

empathy The ability to feel what a person is experiencing by attempting to observe the world through his or her eyes.

genuineness The ability to respond to a client in an authentic way rather than hiding behind a polite or professional mask.

active listening The ability to pick up on the content and emotions behind words in order to understand a client’s perspective, often by echoing the main point of what the client says.

At this point, you may be wondering what exactly the therapist does during sessions. If a client has all the answers, why does he need a therapist at all? Sitting face-

TAKING STOCK: AN APPRAISAL OF HUMANISTIC THERAPY The humanistic perspective has had a profound impact on our understanding of personality development and on the practice of psychotherapy. Therapists of all different theoretical orientations draw on humanistic techniques to build stronger relationships with clients and create positive therapeutic environments. This type of therapy is useful for an array of people dealing with complex and diverse problems (Corey, 2013), but how it compares to other methods remains somewhat unclear. Studying humanistic therapy is difficult because its methodology has not been operationalized and its use varies from one therapist to the next. Like other insight therapies, humanistic therapy is not ideal for everyone; it requires a high level of verbal ability and self-

527

The insight therapies we have explored—

show what you know

Question 1

1. Suzanne is late for her therapy appointment yet again. Her therapist suggests this might be due to _________________, which generally refers to a patient’s unwillingness to cooperate in therapy.

resistance

Question 2

2. The group of therapies known as _________________ therapy focus on the positive nature of human beings and on the here and now.

humanistic

psychoanalytic

psychodynamic

free association

a. humanistic

Question 3

3. Seeing the world through a client’s eyes and understanding how it feels to be the client is called:

interpretation.

genuineness.

empathy.

self-

actualization.

c. empathy.

Question 4

4. What are the differences between psychoanalytic and psychodynamic therapy?

Psychoanalysis, the first formal system of psychotherapy, attempts to increase awareness of unconscious conflicts, making it possible to address and work through them. The therapist’s goal is to uncover these unconscious conflicts. Psychodynamic therapy is an updated form of psychoanalysis; it incorporates many of Freud’s core themes, including the notion that personality characteristics and behavior problems often can be traced to unconscious conflicts. In psychodynamic therapy, therapists see clients once a week for several months rather than many times a week for years. And instead of sitting quietly off to the side, therapists and clients sit face-