1.4 Descriptive Research

LO 8 Recognize the forms of descriptive research.

descriptive research Research methods that describe and explore behaviors, but with findings that cannot definitively state cause-

Suppose a researcher is interested in studying how the sudden arrival of drugs, sweets, and other prohibited goods affects the miners’ social interactions. This is a great topic for descriptive research, the type of investigation psychologists conduct when they need to explore a subject of interest. Descriptive research is primarily concerned with describing, and is useful for studying new or unexplored topics when researchers might not have specific expectations about outcomes. But there are some things descriptive research cannot achieve. This method provides us with clues to the causes of behaviors, but it cannot unearth cause-

Naturalistic Observation

naturalistic observation A type of descriptive research that studies participants in their natural environment through systematic observation.

According to one study, male college students are less conscientious about hand-

One form of descriptive research is naturalistic observation, which involves studying participants in their natural environments using systematic observation. And when we say “natural environments,” we don’t necessarily mean the “wild.” It could be an office, a home, or even a preschool. In one naturalistic study, researchers explored the interactions that occurred when parents dropped off their children at preschool. One variable of interest was the length of time it took parents to leave the children at school. The researchers found that the longer parents or caregivers took to leave, the less time the children played with their peers and the more likely they were to stand by and watch other kids playing. The researchers also noted that women were somewhat more likely than men to hold the children and physically pick them up during drop-

NATURALLY, IT’S A CHALLENGE As with any type of research, naturalistic observation centers around variables, and those variables must be pinned down with operational definitions. Let’s say a researcher is interested in studying aggressiveness in enclosed spaces and decides to examine aggression among Los 33: an intriguing topic given that research has linked stress and hot temperatures to more aggressive behaviors (Anderson, 2001; Fay & Maner, 2014; Kruk, Halász, Meelis, & Haller, 2004). At the beginning of the study, the researcher would need to operationally define aggression, including detailed descriptions of specific behaviors that illustrate it. Then she might create a checklist of aggressive behaviors like shouting and pushing, and a coding system to help keep track of them.

27

Naturalistic observation allows psychologists to observe participants going about their business in their normal environments, without the disruptions of artificial laboratory settings. Perhaps the most important requirement of naturalistic observation is that researchers must not disturb the participants or their environment, so participants won’t change their normal behaviors (particularly those behaviors the researchers wish to observe). Some problems arise with this arrangement, however. Natural environments are cluttered with a variety of unwanted variables, and removing them can alter the natural state of affairs the researchers are striving to maintain. And because the variables in natural environments are so hard to control, researchers may have trouble replicating findings. Suppose the researcher opted to study the behavior of Los 33 during their heated dominoes matches. In this natural setting, she would not be able to control who played and when; whoever showed up at the dominoes table would become a participant in her study.

observer bias Errors introduced into the recording of observations due to a researcher’s value system, expectations, or attitudes.

OBSERVER BIAS How can we be sure observers will do a good job recording behaviors? A researcher who detests dominoes might pay attention to very different aspects of domino-

Case Study

case study A type of descriptive research that closely examines one individual or small group.

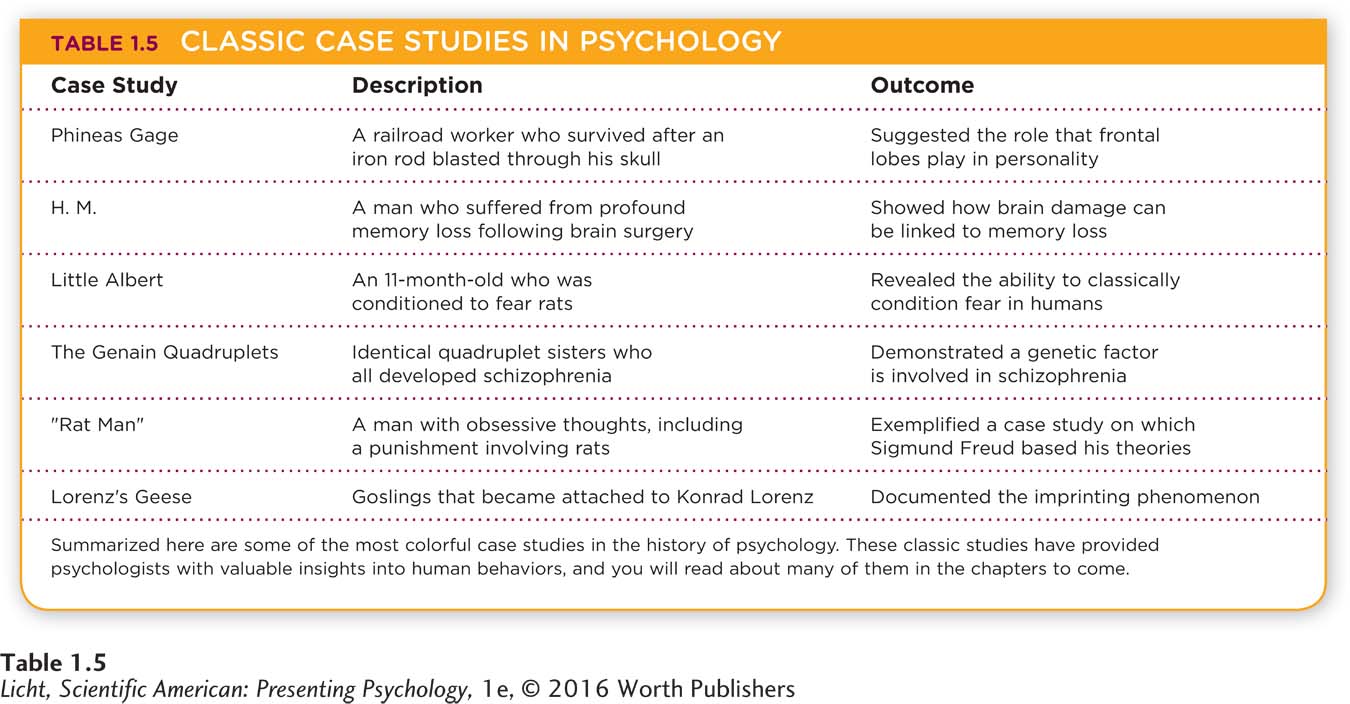

Another type of descriptive research method is the case study, a detailed examination of an individual or small group. Case studies typically involve collecting a vast amount of data on one person or group, often using multiple avenues to gather information. The process might include in-

The subject of one of the most famous case studies in the history of psychology, Kim Peek was able to simultaneously read two pages of a book—

28

No matter how colorful or thought-

Suppose you are trying to examine how parent–

Survey Method

survey method A type of descriptive research that uses questionnaires or interviews to gather data.

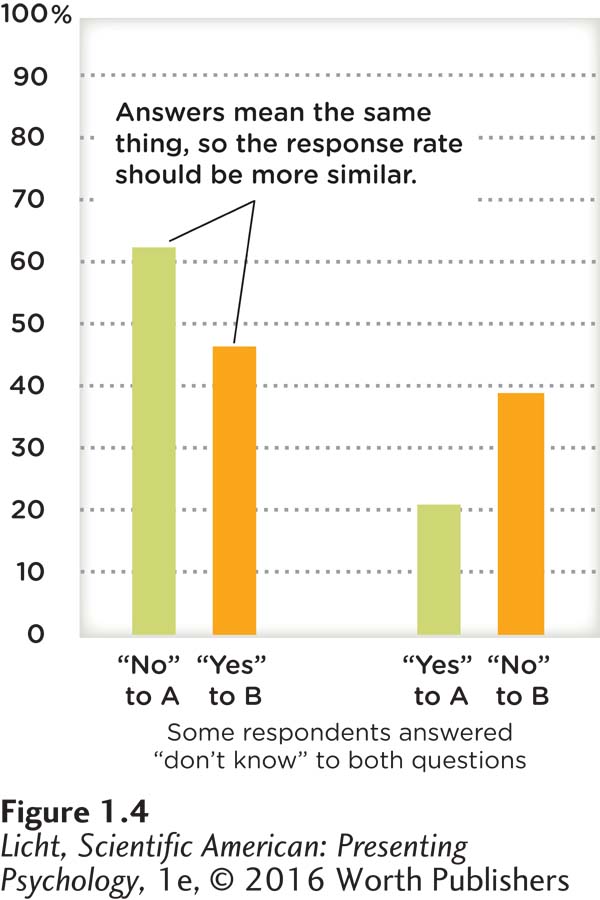

In a classic study, researchers asked two versions of the same question:

(A) Do you think the United States should allow public speeches against democracy?

(B) Do you think the United States should forbid public speeches against democracy?

Answering “no” to Question A (in other words, not allow speeches) should be the same as answering “yes” to Question B (in other words, forbid speeches). However, far more respondents answered “no” to Question A than answered “yes” to Question B. According to the researchers, “the ‘forbid’ phrasing makes the implied threat to civil liberties more apparent” than the “not allow” phrasing does (Rugg, 1941, p. 91). And that’s something fewer people were willing to support.

One of the fastest ways to collect descriptive data is the survey method, which relies on questionnaires or interviews. A survey is basically a series of questions that can be administered on paper, in face-

WORDING AND HONESTY Like any research design, the survey method has its limitations. The wording of surveys can lead to biases in responses. A question with a positive or negative spin may sway a participant’s response one way or the other: Do you prefer a half-

29

More importantly, participants in studies using the survey method are not always forthright in their responses, particularly when they have to admit to things they are uncomfortable discussing face-

SKIMMING THE SURFACE Another disadvantage of the survey method is that it tends to skim the surface of people’s beliefs or attitudes, failing to tap into the complex issues underlying responses. Ask 1,000 people if they intend to exercise regularly, and you might get more than a few affirmative responses. But yes might mean something quite different from one person to the next (“Yes, it crosses my mind, but I can never go through with it” versus “Yes, I have a specific plan, and I have been able to follow through”). To obtain more precise responses, researchers often ask people to respond to statements using a scale that indicates the degree to which they agree or disagree (for example, a 5-

REPRESENTATIVE SAMPLES AND SURVEYS The representativeness of survey samples can also be called into question. Some surveys fail to achieve representative samples because their response rates fall short of ideal. If a researcher sends out 100 surveys to potential participants and only 20 people return them, how can we be sure that the answers of those 20 responders reflect those of the entire group? Without a representative sample, we cannot generalize the survey findings.

Correlational Method

correlational method A type of descriptive research examining the relationships among variables.

correlation An association or relationship between two (or more) variables.

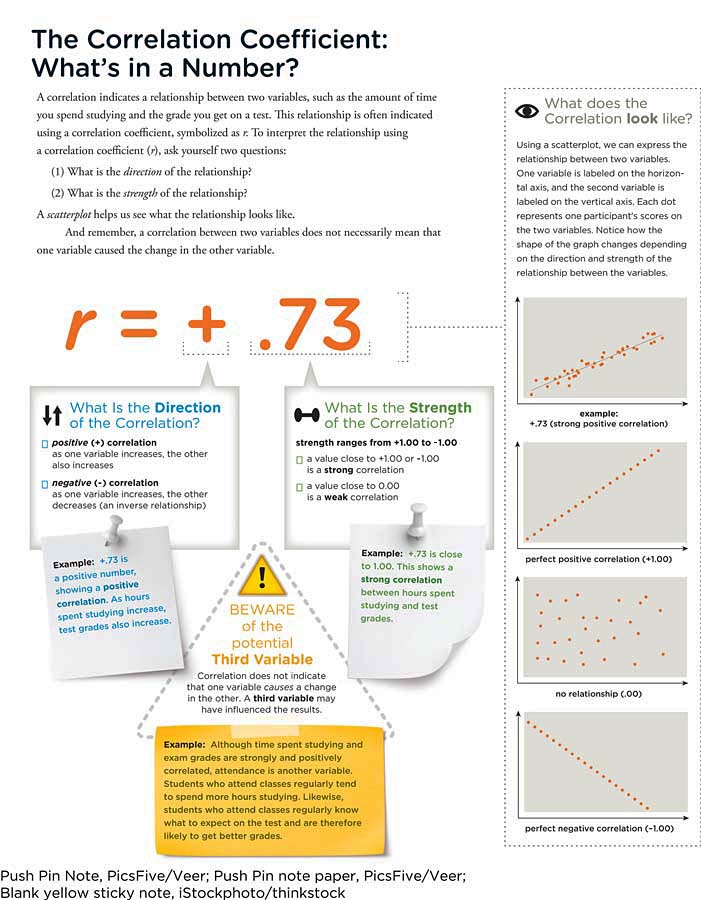

The final form of descriptive research we will cover is the correlational method, which examines relationships among variables and assists researchers in making predictions. When researchers collect data on many variables, it can be useful to determine if these variables are related to each other in some way. A correlation represents a relationship or link between variables (Infographic 1.4, below). For example, there is probably a correlation between the years of working in a mine and yearly salary. The more time a miner has put in, the more cash he takes home. This is an example of a positive correlation. As one variable increases, so does the other. A negative correlation, on the other hand, means as one variable goes up the other goes down (an inverse relationship). A good example would be the number of days trapped in the mine and body weight (at least before rescuers started delivering food). As the number of days increased, the miners’ weight decreased. You have probably noticed correlations between variables in your own life. Increase the hours you devote to studying, and you will likely see your grades go up (a positive correlation). The more you hold a baby, the less she cries (a negative correlation).

30

31

INFOGRAPHIC 1.4

correlation coefficient The statistical measure (symbolized as r) that indicates the strength and direction of the relationship between two variables.

Darío Segovia began to work at the San José mine just 3 months before its collapse, so he would have been at the low end of the pay scale. But working at the notoriously risky mine paid well compared to other mining gigs. Laboring in dangerous conditions is a “third variable” that could influence the relationship between years worked in the mine and salary (Webber, 2010, October 11).

CORRELATION COEFFICIENT Some variables are not related to each other, whereas others have a link between them. Correlations indicate this type of information by representing the strength of the relationship between variables. Some relationships are strong and clear. Others are weak and barely noticeable. Lucky for researchers, there is one number that indicates the relationship’s strength and direction (positive or negative): a statistical measure called the correlation coefficient, which is symbolized as r. Correlation coefficients range from +1.00 to −1.00, with positive numbers indicating a positive relationship between variables and negative numbers indicating an inverse relationship between variables. The closer r is to +1.00 or to −1.00, the stronger the relationship. The closer r is to .00, the weaker the relationship. When the correlation coefficient is very close to zero, there may be no relationship at all between the variables. For example, consider the variables of shoe size and intelligence. Are people with bigger (or smaller) feet more intelligent? Probably not; there would be no link between these two variables, so the correlation coefficient between them (the r value) is around zero. Take a look at Infographic 1.4 to see how correlation coefficients are portrayed on graphs called scatterplots.

Synonyms

third variable third factor

third variable An unaccounted for characteristic of participants or the environment that explains changes in the variables of interest.

THIRD VARIABLE Even if there is a very strong correlation between two variables, this does not indicate there is a causal link between them. No matter how high the r value is or how logical the relationship seems, it does not prove a cause-

Remember, correlational and other descriptive methods can’t identify the causes of behaviors. But this type of research can provide clues to what underlies behaviors, and thus it serves as a valuable tool when other types of experiments are unethical or impossible to conduct (in the previous example, researchers couldn’t ethically manipulate real-

32

across the WORLD

The Many Faces of Facebook

You probably know that Facebook is the most widely used social networking site in the world, far more popular than Twitter and LinkedIn (eBizMBA, 2015). But you may be surprised to learn that 82% of Facebook’s billion-

You probably know that Facebook is the most widely used social networking site in the world, far more popular than Twitter and LinkedIn (eBizMBA, 2015). But you may be surprised to learn that 82% of Facebook’s billion-

WHAT’S THE NUMBER ONE REASON PEOPLE USE FACEBOOK?

Curious about patterns of Facebook use across time and culture, a team of European researchers set out to gather data from users in different countries (Vasalou, Joinson, & Courvoisier, 2010). With the help of Facebook walls and networks, they recruited 423 Facebook users from the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy, Greece, and France. Then they asked the participants to complete an online questionnaire and conducted a statistical analysis of the responses. Their findings were intriguing.

Across cultures, the primary motivation for using Facebook was “social searching,” or connecting with people already known outside of Facebook (friends, family, colleagues, and so on). In second place was “social browsing,” or looking for new acquaintances, which was particularly popular among French and Italian users. When it came to total time investment in Facebook, the British led the pack, averaging between 2 and 5 hours per week (compared to 2 hours or less for those in other countries). French and Greek users were not particularly interested in status updates, and the French did not place a high value on photographs (Vasalou et al., 2010). What do all these findings mean? The answer to this question is beyond the scope of the study. Surveys and other forms of descriptive research are information-

show what you know

Question 1

1. ____________ is primarily useful for studying new or unexplored topics.

An operational definition

Observer bias

Descriptive research

A correlation

c. Descriptive research

Question 2

2. A researcher was interested in studying the behaviors of parents dropping off children at preschool. He trained several teachers to use a checklist and a stopwatch to record how long it took a caregiver to enter and leave the classroom, as well as the subsequent behaviors of the children. This approach to collecting data is referred to as:

naturalistic observation.

representative sampling.

informed consent.

applied research.

a. naturalistic observation.

Question 3

3. Describe the strengths and weaknesses of descriptive research.

Descriptive research explores and describes behaviors. This approach is excellent for investigating unfamiliar topics. A researcher conducting such a study has few or no specific expectations about outcomes, and may use his findings to direct future research. A critical weakness of descriptive research is that it cannot uncover cause-