4.1 An Introduction to Consciousness

129

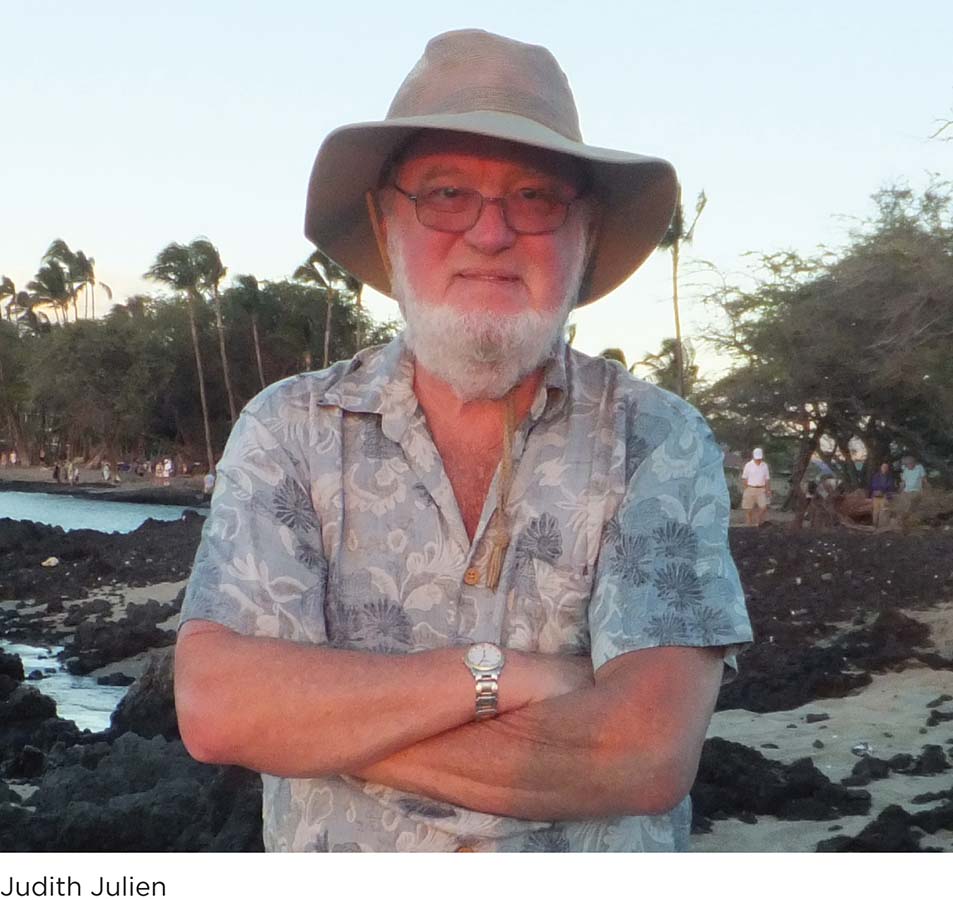

Dr. Robert Julien is an anesthesiologist, a physician who keeps patients comfortable and monitors their vital signs during surgery. Anesthesiologists administer drugs that interfere with pain, paralyze the muscles, and induce a sleeplike state. How these substances alter consciousness is still somewhat mysterious (Geddes, 2011, November 29).

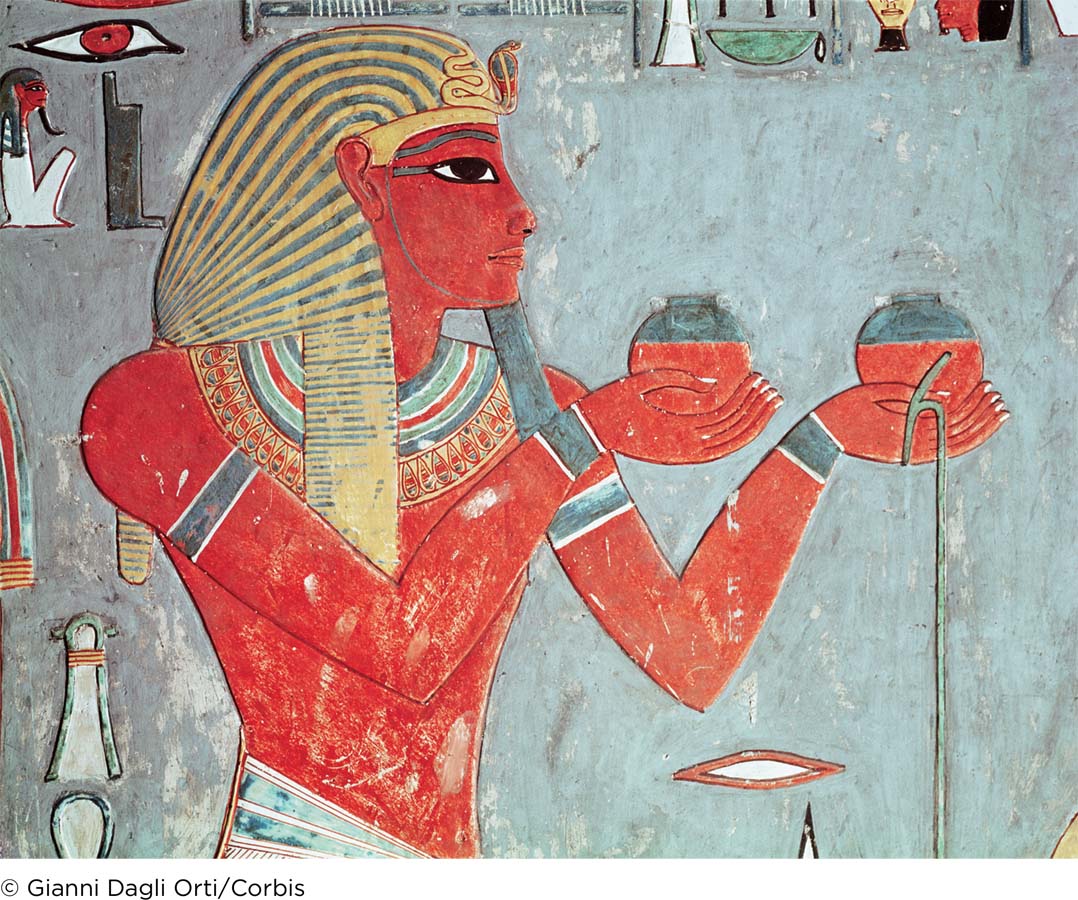

Wall art from the Tomb of Horemheb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings depicts a person holding two round vessels representing poppy flowers. The ancient Egyptians used the poppy opiate morphine for pain relief, but its therapeutic role was controversial (El Ansary et al., 2003).

MIND-

In ancient times, people may have sought pain relief by dipping their wounds in cold rivers and streams. They concocted mixtures of crushed roots, barks, herbs, fruits, and flowers to ease pain and induce sleep in surgical patients (Keys, 1945). Many of the plant chemicals discovered by these early peoples are still given to patients today, although in slightly different forms. Opium was used by the ancient Egyptians (El Ansary, Steigerwald, & Esser, 2003), and its chemical relatives are used by modern-

Nevertheless, it took many centuries for anesthesia to become a regular part of surgery. Before the mid-

Note: Unless otherwise specified, quotations attributed to Dr. Robert Julien and Matt Utesch are personal communications.

130

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, you should be able to:

LO 1 Define consciousness.

LO 2 Explain how automatic processing relates to consciousness.

LO 3 Describe how we narrow our focus through selective attention.

LO 4 Identify how circadian rhythm relates to sleep.

LO 5 Summarize the stages of sleep.

LO 6 Recognize various sleep disorders and their symptoms.

LO 7 Summarize the theories of why we dream.

LO 8 Define psychoactive drugs.

LO 9 Identify several depressants and stimulants and know their effects.

LO 10 Discuss some of the hallucinogens.

LO 11 Explain how physiological and psychological dependence differ.

LO 12 Describe hypnosis and explain how it works.

LO 1 Define consciousness.

consciousness The state of being aware of oneself, one’s thoughts, and/or the environment; includes various levels of conscious awareness.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we introduced the evolutionary perspective. The adaptive trait to remain aware even while asleep has evolved through natural selection, allowing our ancestors to defend against predators and other dangerous situations.

Consciousness is a concept that can be difficult to pinpoint. Psychologist G. William Farthing offers a good starting point: Consciousness is “the subjective state of being currently aware of something either within oneself or outside of oneself” (1992, p. 6). Consciousness is best defined as the state of being aware of oneself, one’s thoughts, and/or the environment. According to this definition of subjective awareness, one can be asleep and still be aware (Farthing, 1992). Consider this example: You are dreaming about a siren blaring and you wake up to discover it is your alarm clock; you were clearly asleep but aware at the same time, as the sound registered in your brain. This ability to remain aware while asleep was especially useful for our primitive ancestors, who needed to be vigilant about dangers day and night.

Consciousness and Memory

Several years ago, Dr. Julien had a patient who didn’t want to have general anesthesia during her hysterectomy, an operation to remove the uterus. Anesthesiologists typically put patients “to sleep” for hysterectomies, but Dr. Julien agreed to honor the patient’s unusual request. He gave her a drug called Versed (midazolam) to help her relax, but not enough to knock her out. (Versed belongs to a class of calming drugs called depressants, which you will learn about later.) The woman seemed to be wide awake throughout the 21/2-hour procedure, chatting with doctors and nurses and even requesting that certain music be played in the operating room (much to the dismay of the surgical team).

A patient lies awake on the operating table as doctors stimulate his brain with electrical currents. With the right combination of anesthetics, a patient can be wide awake yet feel no pain and form no lasting memory of the procedure.

131

At 11:00 P.M. that night, a nurse called Dr. Julien saying the patient was furious that he had used general anesthesia during the operation (which he had not done). The drug Dr. Julien had used to help the patient relax can also cause memory loss for events experienced while under its influence. Unable to remember the surgery, the patient logically assumed she had been given general anesthesia. “I went to the hospital at midnight to explain to the patient that I had honored her request and that she had been wide awake during the procedure but was unable to form memory proteins because the Versed had blocked their formation,” Dr. Julien explained. In other words, the Versed had interfered with the production of a protein needed for memory creation. “To this day, I’m not sure she ever accepted my explanation or forgave me for taking away any memory of the procedure” (Julien & DiCecco, 2010, p. 11).

Would you say Dr. Julien’s patient was conscious during the operation? If consciousness is a “subjective state of being currently aware” (Farthing, 1992, p. 6), then it would appear she was conscious during the surgery. She was alert and talking, yet her awareness of the event vanished within hours. Was this a problem with her consciousness or her memory? Although memory plays an important role in conscious processes, it is not equivalent to consciousness. The patient appeared to be “aware” during the procedure, but later had no memory of the event. As Dr. Julien explained to her, a failure occurred in the process involved in memory formation, perhaps in the encoding or storage of the event (Chapter 6).

Millions of Americans suffer from memory problems similar to that experienced by Dr. Julien’s patient. They are aware, alert, and able to have meaningful conversations, yet they cannot form new memories because they suffer from Alzheimer’s (Chapter 6) or another form of dementia. There are also people who cannot form memories because they are taking consciousness-

Studying Consciousness

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the contributions of these early psychologists. Wundt founded the first psychology laboratory, edited the first psychological journal, and used experimentation to measure psychological processes. Titchener was particularly interested in examining consciousness and the “atoms” of the mind.

The field of psychology began with the study of consciousness. Wilhelm Wundt and his disciple Edward Titchener founded psychology as a science based on exploring consciousness and its contents. Another early psychologist, William James, regarded consciousness as a “stream” that provides a sense of day-

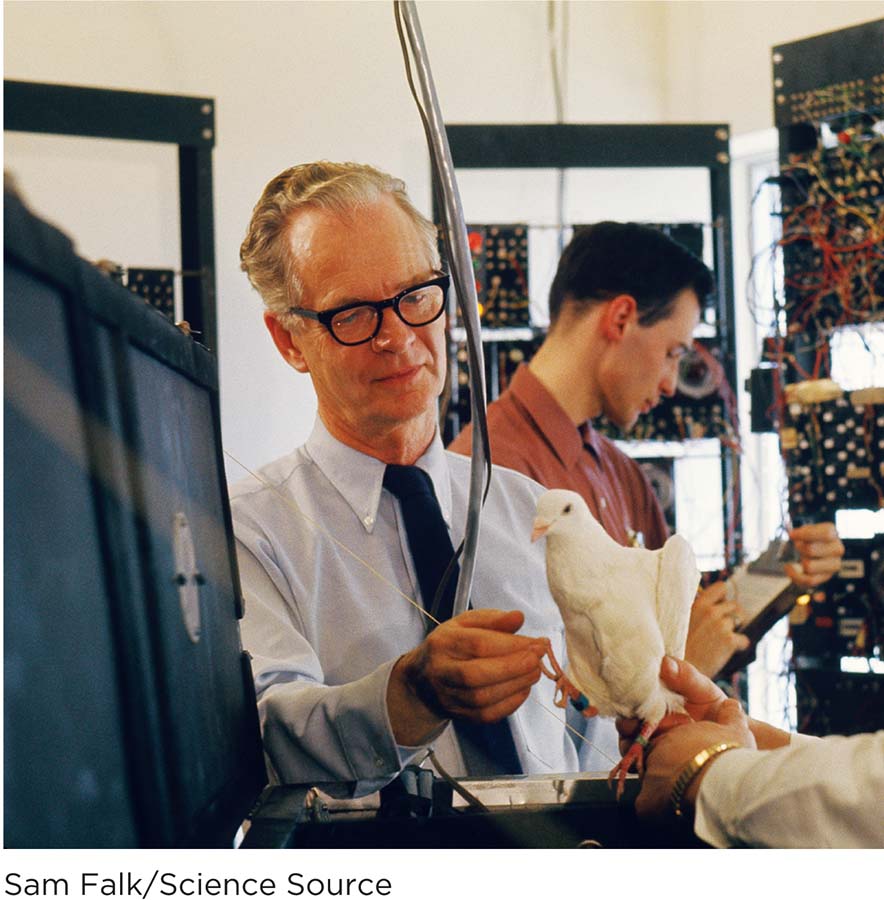

B. F. Skinner works with a pigeon in the laboratory. A die-

Although psychology started with the introspective study of consciousness, American psychologists John Watson, B. F. Skinner, and other behaviorists insisted that the science of psychology should restrict itself to the study of observable behaviors. This attitude persisted until the 1950s and 1960s, when psychology underwent a revolution of sorts. Researchers began to direct their focus back on the unseen mechanisms of the mind. Cognitive psychology, the scientific study of conscious processes such as thinking, problem solving, and language, emerged as a major subfield. Today, understanding consciousness is an important goal of psychology, and many believe science can be used to investigate its mysteries.

132

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we presented the concept of objective reports, which are free of opinions, beliefs, expectations, and values. Here, we note that descriptions of consciousness are more subjective in nature, and do not lend themselves to objective reporting.

Advanced technology for examining brain processes and functions has added to our growing knowledge of consciousness, but barriers to studying it remain. One is that consciousness is subjective, pertaining only to the individual who experiences it. Thus, it is impossible to objectively study another’s conscious experience (Blackmore, 2005; Farthing, 1992). To make matters more complicated, one’s consciousness changes from moment to moment. Right now you are concentrating on these words, but in a few seconds you might be thinking of something else or slip into light sleep. In spite of these challenges, researchers around the world are inching closer to understanding consciousness by studying it from many perspectives. Welcome to the world of consciousness and its many shades of gray.

The Nature of Consciousness

There are many elements of conscious experience, including desire, thought, language, sensation, perception, knowledge of self, and of course memory, as conscious experiences usually involve the retrieval of memories. Simply stated, any cognitive process is potentially a part of your conscious experience. Let’s look at what this means, for example, when you go shopping on the Internet. Your ability to navigate from page to page hinges on your recognition of visual images (Is that the PayPal home page or my e-

Stop reading and listen. Do you hear background sounds you didn’t notice before—

try this

LO 2 Explain how automatic processing relates to consciousness.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 3, we introduced the concept of sensory adaptation, which is the tendency to become less sensitive to and less aware of constant stimuli after a period of time. This better prepares us to detect changes in the environment, which can signal important activities that require our attention. Here, we see how this can occur through automatic processing.

automatic processing Detection, encoding, and sometimes storage of information without conscious effort or awareness.

Do you recall dropping your keys in your bag this morning? Many routine activities, such as putting away keys and locking the door, occur without our awareness. We might not remember these events because we never gave them our attention in the first place.

AUTOMATIC PROCESSING In describing consciousness, psychologists often distinguish between cognitive processes that occur automatically (without effort, awareness, or control) and cognitive activity that requires us to focus our attention on specific sensory input (with effort and awareness, we choose what to attend to and where to direct our focus). Our sensory systems absorb an enormous amount of information, and the brain must sift through this data and determine what is important and needs immediate attention, what can be ignored, and what can be processed and stored for later use. This automatic processing allows information to be collected and saved (at least temporarily) with little or no conscious effort (McCarthy & Skowronski, 2011; Schmidt-

Automatic processing can also refer to the involuntary cognitive activity guiding some behaviors. We are seemingly able to behave and act without focusing our attention. Behaviors seem to occur without intentional awareness, and without getting in the way of our other activities (Hassin, Bargh, & Zimerman, 2009). Do you remember the last time you drove your car on a familiar route, daydreaming the entire time? Somehow you arrived at your destination without noticing much about your driving, the traffic, and so forth. Or have you ever been listening to music while cleaning the kitchen, and then realized you were almost finished without once being aware that you had scrubbed the countertop or mopped the floor? You were conscious enough to complete complex tasks, but not enough to realize that you were doing so.

133

Although unconscious processes direct various behaviors, we can also make conscious decisions about where to focus our attention. While walking to class you might focus intently on a conversation you just had with your friend or an exam you will take in an hour. With this type of conscious activity, we deliberately channel or direct our attention.

LO 3 Describe how we narrow our focus through selective attention.

selective attention The ability to focus awareness on a small segment of information that is available through our sensory systems.

SELECTIVE ATTENTION Although we have access to a vast amount of information in our internal and external environments, we can only focus our attention on a small portion at one time. This narrow focus on specific stimuli is known as selective attention. Talking to someone in a crowded room, you are able to block out the chatter and noise around you and immerse yourself in the conversation. This efficient use of selective attention is known as the cocktail-

This doesn’t mean other information goes undetected (remember we are constantly gathering data through automatic processing). Our tendency is to adapt to continuous input, and ignore the unimportant sensory stimuli that bombard us every moment. We are designed to pay attention to abrupt, unexpected changes in the environment, and to stimuli that are unfamiliar or especially strong (Bahrick & Newell, 2008; Daffner et al., 2007; Parmentier & Andrés, 2010). Imagine you are studying in a busy courtyard. You are aware the environment is bustling with activity, but you fail to pay attention to every person—

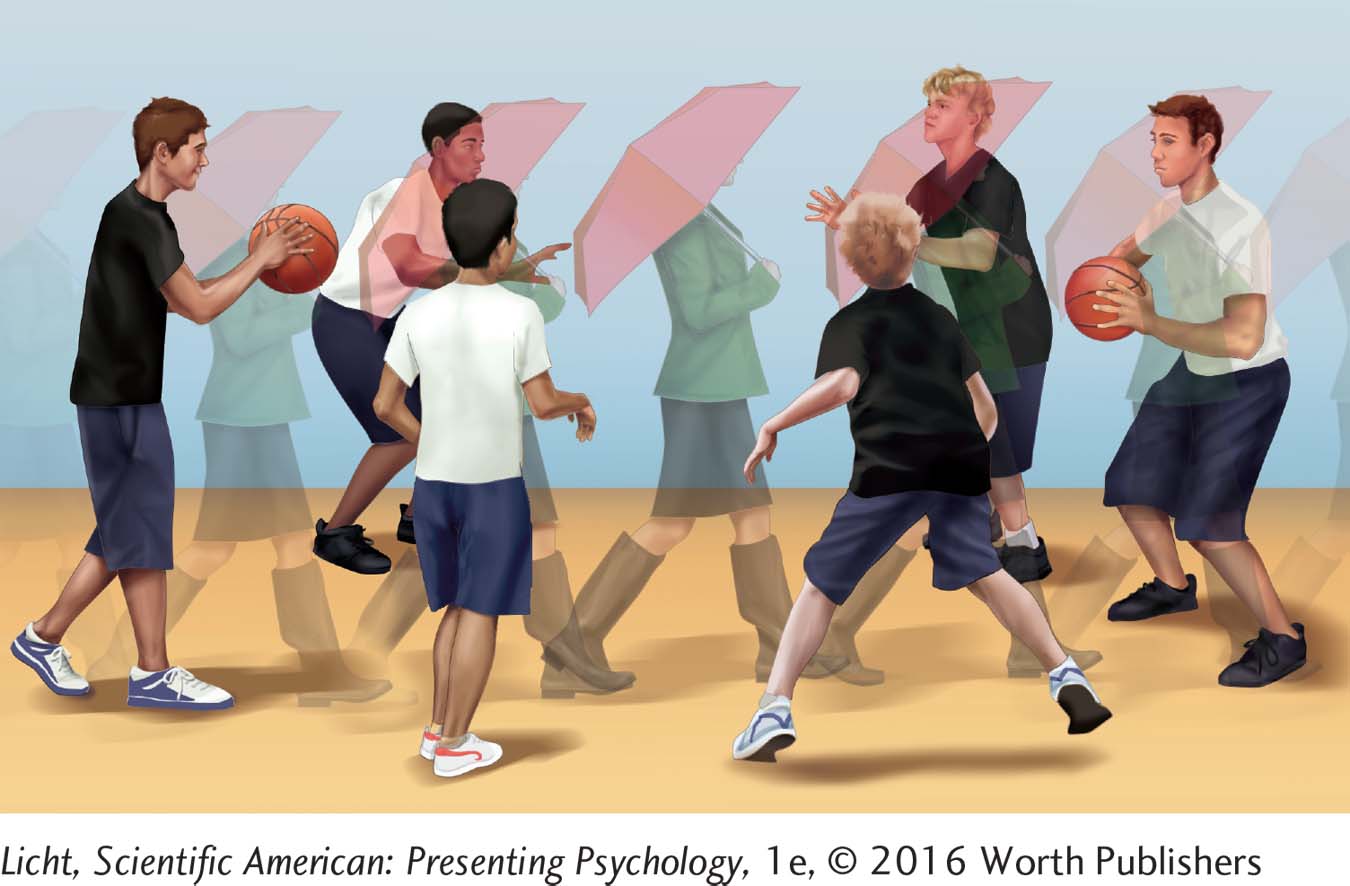

In an elegant demonstration of inattentional blindness, researchers asked a group of participants to watch a video of men passing around a basketball. As the participants kept careful tabs on the players’ passes, a semi-

134

INATTENTIONAL BLINDNESS Selective attention is great if you need to study for a psychology test while others are watching a movie, but it can also be dangerous. Suppose a friend sends you a hilarious text message while you are walking toward a busy intersection. Thinking about the text can momentarily steal your attention away from signs of danger, like a car turning right on red without stopping. While distracted by the text message, you might step into the intersection—

Ulric Neisser illustrated just how blind we can be to objects directly in our line of vision. In one of his studies, participants were instructed to watch a video of men passing a basketball from one person to another (Neisser, 1979; Neisser & Becklen, 1975). As the participants diligently followed the basketball with their eyes, counting each pass, a partially transparent woman holding an umbrella was superimposed walking across the basketball court. Only 21% of the participants even noticed the woman (Most et al., 2001; Simons, 2010); the others had been too fixated on counting the basketball passes to see her (Mack, 2003).

LEVELS OF CONSCIOUSNESS People often equate consciousness with being awake and alert, and unconsciousness with being passed out or comatose. But the distinction is not so clear, because there are different levels of conscious awareness including wakefulness, sleepiness, drug-

Wherever your attention is focused at this moment, that is your conscious experience—

show what you know

Question 1

1. One barrier to studying consciousness is the fact that it is _________________ , pertaining only to the person who experiences it.

subjective

Question 2

2. While studying for an exam, your sensory systems absorb an inordinate amount of information from your surroundings, most of which escapes your awareness. Because of _________________ , you generally do not get overwhelmed with incoming sensory data.

consciousness

automatic processing

depressants

encoding

b. automatic processing

Question 3

3. Inattentional blindness is the tendency to “look without seeing.” Given what you know about selective attention, how would you advise someone to avoid inattentional blindness?

Answers will vary. The ability to focus awareness on a small segment of information that is available through our sensory systems is called selective attention. Although we are exposed to many different stimuli at once, we tend to pay particular attention to abrupt or unexpected changes in the environment. Such events may pose a danger and we need to be aware of them. However, selective attention can cause us to be blind to objects directly in our line of vision. This “looking without seeing” can have serious consequences, as we fail to see important occurrences in our surroundings. Our advice would be to try to remain aware of the possibility of inattentional blindness, in particular when you are in situations that could involve serious injury.