8.4 Adolescence

Members of the St. Thomas Boys Choir in Leipzig, Germany, practice a chant in rehearsal. Choir directors are struggling with the fact that young boys’ voices are deepening earlier as the years go by. In the mid-

333

THE WALKING, TALKING HORMONE Jocelyn is no longer a cute little bundle of girlhood; nowadays, she is a “walking, talking hormone,” says Jasmine. “Boys, make-

THE WALKING, TALKING HORMONE Jocelyn is no longer a cute little bundle of girlhood; nowadays, she is a “walking, talking hormone,” says Jasmine. “Boys, make-

adolescence The transition period between late childhood and early adulthood.

Jocelyn’s behaviors are stereotypical of teenagers, or adolescents. Adolescence refers to the transition period between late childhood and early adulthood, and it can be challenging for both parents and kids. As you may recall from earlier in the chapter, Jasmine proved to be quite a challenge for her own mom when she was a teen, skipping school and carousing until late at night with friends. “At 14, I had already started the crazy life,” says Jasmine, who considers herself blessed to have a daughter like Jocelyn, who gets As and Bs in her classes, doesn’t use drugs or alcohol, and participates in her school’s volleyball, basketball, and dance teams.

In the United States, adult responsibilities often are distant concepts for adolescents. But this is not universal. For example, in underdeveloped countries, children take on adult responsibilities as soon as they are able. In some parts of the world, girls younger than 18 are already married and dealing with grown-

Physical and Cognitive Development in Adolescence

LO 12 Give examples of significant physical changes that occur during adolescence.

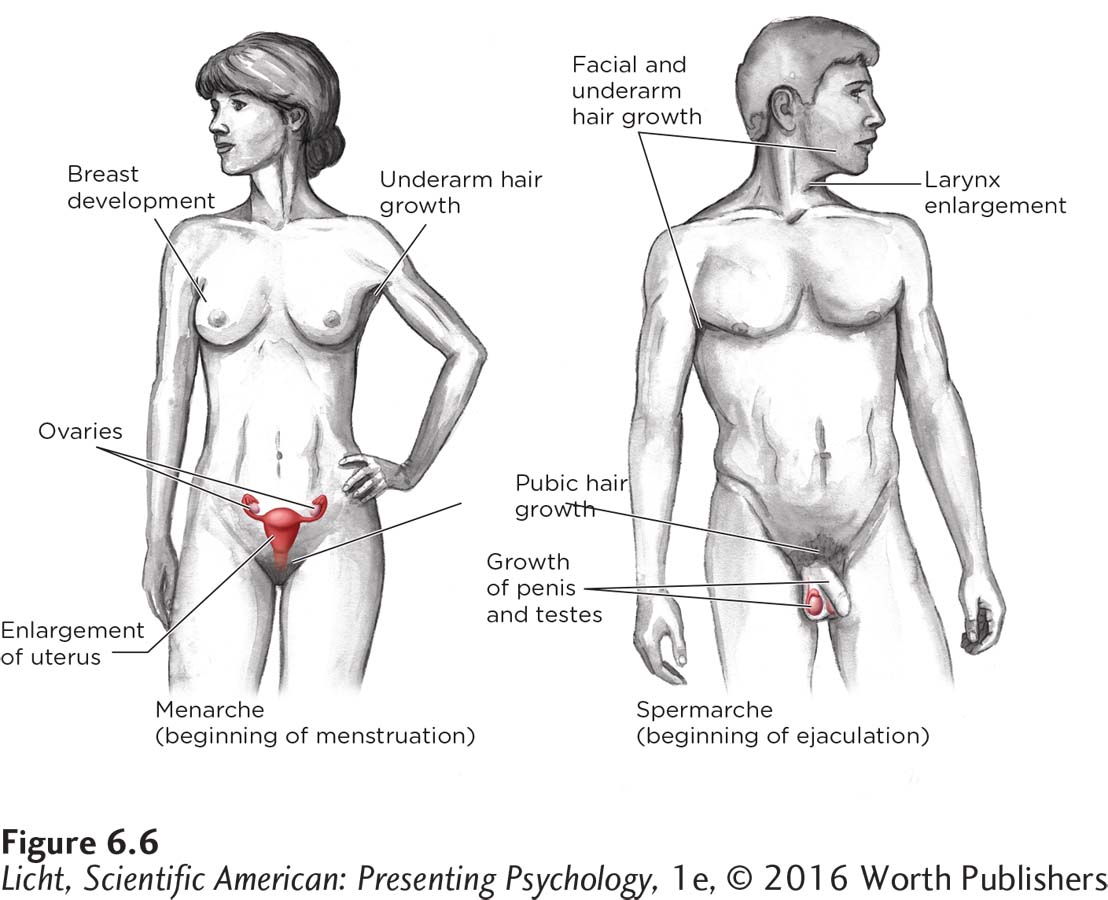

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT Adolescence is a time of dramatic physical growth, comparable to that which occurs during fetal development. The “growth spurt” includes rapid changes in height, weight, and bone growth, and usually begins between ages 9 and 10 for girls and ages 12 and 16 for boys. Sex hormones, which influence this growth and development, are at high levels.

puberty The period of development during which the body changes and becomes sexually mature and capable of reproduction.

primary sex characteristics Organs associated with reproduction, including the ovaries, uterus, vagina, penis, scrotum, and testes.

secondary sex characteristics Body characteristics, such as pubic hair, underarm hair, and enlarged breasts, that develop in puberty but are not associated with reproduction.

Puberty is the period during which the body changes and becomes sexually mature and able to reproduce (Figure 8.5, below). During puberty, the primary sex characteristics (reproductive organs) mature; these include the ovaries, uterus, vagina, penis, scrotum, and testes. At the same time, the secondary sex characteristics (physical features not associated with reproduction) become more distinct; these include pubic, underarm, and body hair. Breast changes also occur in boys and girls (with the areola increasing in size), and fat increases in girls’ breasts. Adolescents experience changes to their skin and overall body hair. Girls’ pelvises begin to broaden, while boys experience a deepening of their voices and broadening of their shoulders.

During puberty, the body changes and becomes sexually mature and able to reproduce. The primary sex characteristics mature, and the secondary sex characteristics become more distinct. Primary sex characteristics are related to reproductive organs. The reproductive organs, present at birth, begin to function differently at puberty. For instance, the testes and ovaries are involved in stimulating more visible changes, such as breast development and growth of the penis.

menarche ('me-

spermarche ('spər-

It is during this time that girls experience menarche ('me-

334

Not everyone goes through puberty at the same time. Some evidence suggests that early maturing adolescents face a greater risk of engaging in unsafe behaviors, such as drug and alcohol use (Shelton & van den Bree, 2010). Compared to their peers, girls who mature early seem to experience more negative outcomes than those who mature later, including increased anxiety, particularly social anxiety; they also appear to face a higher risk of emotional problems and delinquent behaviors (Blumenthal et al., 2011; Harden & Mendle, 2012). Early maturing girls are more likely to smoke, drink alcohol, have lower self-

Boys who mature early generally have a more positive experience and do not show evidence of increased anxiety (Blumenthal et al., 2011). But, when researchers examine the “tempo,” or speed, with which boys reach full sexual maturity, they find that rapid development can be associated with a range of problems, including aggressive behavior, cheating, and temper tantrums (Marceau, Ram, Houts, Grimm, & Susman, 2011).

Synonyms

sexually transmitted infections sexually transmitted diseases

Adolescence is a time when sexual interest peaks, yet teenagers don’t always make the best choices when it comes to sexual activity. A study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2008a) found that over 25% of girls (approximately 1 in 4) between ages 14 and 19 are infected with “at least one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases” (para. 1). Over half of new sexually transmitted infections affect young people ages 15–

LO 13 Explain how Piaget described cognitive changes that take place during adolescence.

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Alongside the remarkable physical changes of adolescence are equally remarkable cognitive developments. As noted earlier, children in this age range are better able to distinguish between abstract and hypothetical situations. This ability is an indication that a teenager has entered Piaget’s formal operational stage, which begins in adolescence and continues into adulthood. During this period, the adolescent begins to use deductive reasoning to draw conclusions and critical thinking to approach arguments. She can reason abstractly, classify ideas, and use symbols. The adolescent can think beyond the current moment, pondering the future and considering many possibilities. She may begin to contemplate what will happen beyond high school, including career choices and education.

335

A teen inmate sits in her room at a maximum-

A specific type of egocentrism emerges in adolescence. Before this age, children can only imagine the world from their own perspective, but during adolescence they begin to be aware of others’ perspectives. Egocentrism is still apparent, however, as they believe others share their preoccupations. For example, a teenager who focuses on his appearance will think that others are focusing on his appearance as well (Elkind, 1967). Adolescents also tend to believe that everyone thinks the same way they do.

This intense focus on the self may lead to a feeling of immortality, which can result in risk-

THE ADOLESCENT BRAIN Risk taking in adolescence is thought to result from characteristics of the adolescent brain. The limbic system, which is responsible for processing emotions and perceiving rewards and punishments, undergoes significant development during adolescence. Another important change is the increased myelination of axons in the prefrontal cortex, which improves the connections within the brain involved in planning, weighing consequences, and multitasking (Steinberg, 2012). But the relatively quicker development of the limbic system in comparison to the prefrontal cortex can lead to risk-

Socioemotional Development in Adolescence

identity A sense of self based on values, beliefs, and goals.

Adolescence is also a time of great socioemotional development. During this period, children become more independent from their parents. Conflicts may result as an adolescent searches for his identity, or sense of who he is based on his values, beliefs, and goals. Until this point in development, the child’s identity was based primarily on the parents’ or caregivers’ values and beliefs. Adolescents explore who they are by trying out different ideas in a variety of categories, including politics and religion. Once these areas have been explored, they begin to commit to a particular set of beliefs and attitudes, making decisions to engage in activities related to their evolving identity. However, their commitment may shift back and forth, sometimes on a day-

336

LO 14 Describe how Erikson explained changes in identity during adolescence.

ERIKSON AND ADOLESCENCE Erikson’s theory of development addresses this important issue of identity formation (Erikson & Erikson, 1997). The time from puberty to the twenties is the stage of ego identity versus role confusion, which is marked by the creation of an adult identity. The adolescent strives to define himself. If the tasks and crises of Erikson’s first four psychosocial stages have not been successfully resolved, the adolescent may enter this stage with distrust toward others, and feelings of shame, guilt, and inadequacy (see Table 8.3). In order to be accepted, he may try to be all things to all people.

It is during this period that one wrestles with some important life questions: What career do I want to pursue?What kind of relationship should I have with my parents?What religion (if any) is compatible with my views, beliefs, and goals? This stage often involves “trying out” different roles. A person who resolves this stage successfully emerges with a stronger sense of her values, beliefs, and goals. One who fails to resolve role confusion will not have a solid sense of identity and may experience withdrawal, isolation, or continued role confusion. However, just because we reach adulthood doesn’t mean our identity stops evolving. As we will soon see, there is still plenty of growth throughout life.

Relationships between teens and parents are generally positive, but most involve some degree of conflict. Many disputes center on everyday issues, like clothing and chores, but the seemingly endless bickering does have a deeper meaning. The adolescent is breaking away from his parents, establishing himself as an autonomous person.

PARENTS AND ADOLESCENTS What role does a parent play during this difficult period? Generally speaking, parent–

FRIENDS Friends become increasingly influential during adolescence. Some parents express concern about the negative influence of peers; however, it is typical for adolescents to form relationships with others of the same age and with whom they might share beliefs and interests. These friendships tend to support the types of behaviors and beliefs parents encouraged during childhood (McPherson, Smith-

337

SOCIAL MEDIA and psychology

The Social Networking Teen Machine

Social media provide an easy way for young people to create and cultivate relationships, but the quality of some of these associations is questionable. Experts worry that teenagers place excessive importance on the number of online interactions they have, rather than the depth of those interactions (Fox News, 2013, March 20). Another concern is that social media may serve as staging grounds for negative behaviors like bullying. According to one survey, approximately 8% of Internet-

Social media provide an easy way for young people to create and cultivate relationships, but the quality of some of these associations is questionable. Experts worry that teenagers place excessive importance on the number of online interactions they have, rather than the depth of those interactions (Fox News, 2013, March 20). Another concern is that social media may serve as staging grounds for negative behaviors like bullying. According to one survey, approximately 8% of Internet-

NETWORK BULLIES AND FRIENDS

But it’s not all bad news. The majority of teens who use social media say that their interactions through these networks have made them feel better about themselves and more deeply connected to others (Lenhart et al., 2011). Online communities provide teens with a space to explore their identities and interact with people from diverse backgrounds. They serve as platforms for the exchange of ideas and art (sharing music, videos, and blogs), and places for students to study and collaborate on school projects (O’Keeffe, Clarke-

Social media are here to stay, and will continue to impact the socioemotional development of adolescents. The challenge for parents is to find ways to direct this online activity while still recognizing their child’s need for space and autonomy (Yardi & Bruckman, 2011). What steps do you think parents should take to ensure that teenagers are using social media in a positive way?

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

LO 15 Summarize Kohlberg’s levels of moral development.

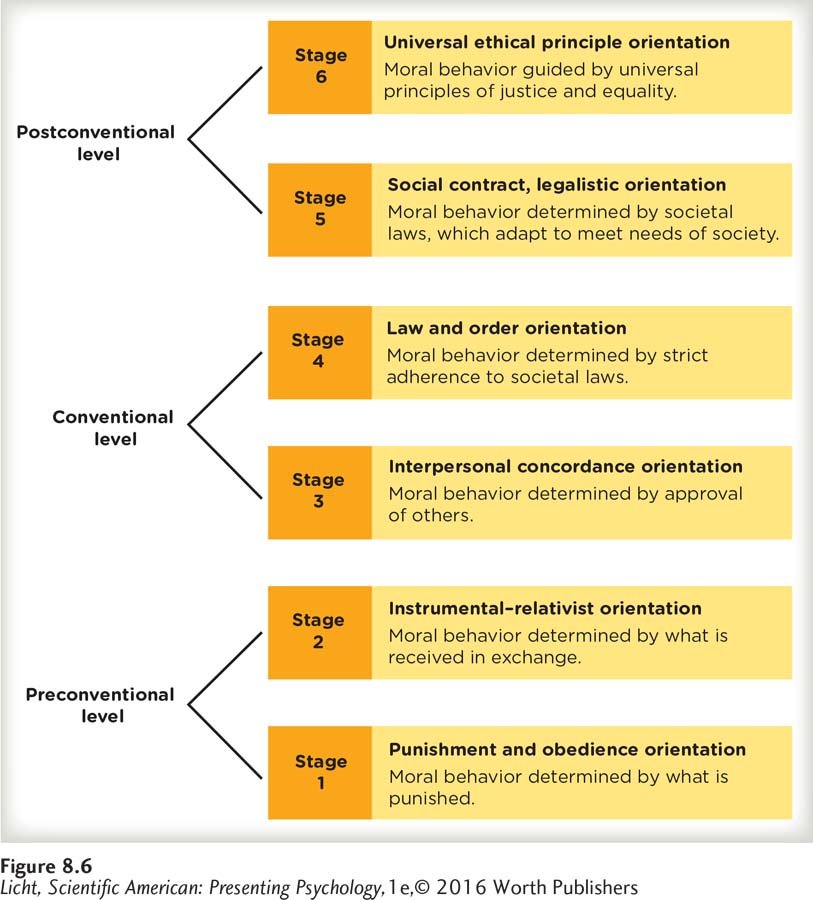

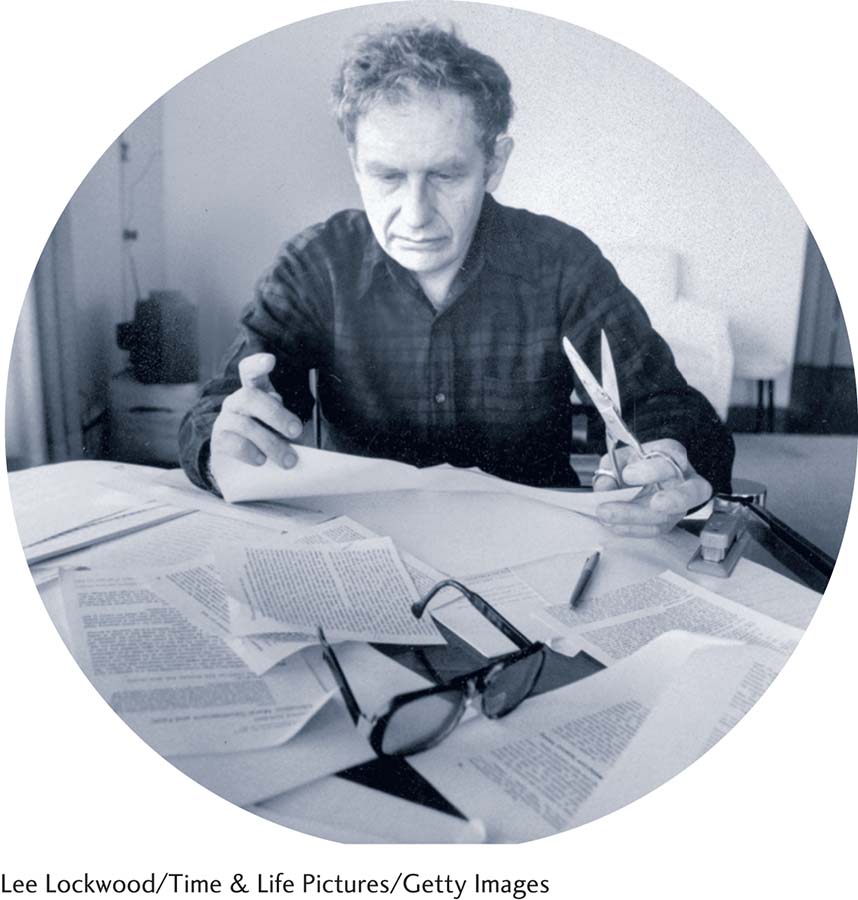

Moral development is another important aspect of socioemotional growth. Lawrence Kohlberg (1927–

American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg proposed that moral reasoning progresses through three major levels: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. The rate at which we move through these developmental levels partly depends on environmental factors, such as interactions with parents and siblings. Critics contend that Kohlberg’s research focused too heavily on men in Western cultures (Endicott, Bock, & Narvaez, 2003; Gilligan, 1982).

Kohlberg used a variety of fictional stories about moral dilemmas to determine the stage of moral reasoning of participants in his studies. The Heinz dilemma is a story about a man named Heinz who was trying to save his critically ill wife. Heinz did not have enough money to buy a drug that could save her, so after trying unsuccessfully to borrow money, he finally decided to steal the drug. The two questions asked of individuals in Kohlberg’s studies were these: “Should the husband have done that? Was it right or wrong?” (Kohlberg, 1981, p. 12). Kohlberg was not really interested in whether his participants thought Heinz should steal the drug or not; instead, the goal was to determine the moral reasoning behind their answers.

Although Kohlberg described moral development as sequential and universal in its progression, he noted that environmental influences and interactions with others (particularly those at a higher level of moral reasoning) support its continued development. Additionally, not everyone progresses through all three levels; an individual may get stuck at an early stage and remain at that level of morality throughout life. Let’s look at these three levels.

preconventional moral reasoning Kohlberg’s stage of moral development in which a person, usually a child, focuses on the consequences of behaviors, good or bad, and is concerned with avoiding punishment.

338

PRECONVENTIONAL MORAL REASONING From the time a toddler or preschooler begins to understand the connection between behavior and its consequences, she can begin to think about moral issues and make decisions about what is right and wrong. Preconventional moral reasoning usually applies to young children, and it focuses on the consequences of behaviors, both good and bad. For children in Stage 1 (punishment and obedience orientation), “goodness” and “badness” are determined by whether a behavior is punished. For example, a child decides not to cheat on a test because she is worried about getting caught and then punished. Thus, consequences drive the belief about what is right and wrong. Regarding the Heinz dilemma, a child at this level may say the husband should not steal the drug because he may go to jail if caught. Children in Stage 2 (instrumental–

conventional moral reasoning Kohlberg’s stage of moral development that determines right and wrong from the expectations of society and important others.

CONVENTIONAL MORAL REASONING At puberty, conventional moral reasoning is used, and determining right and wrong is informed by expectations from society and important others, not simply personal consequences. The emphasis is on conforming to society’s rules and regulations. In Stage 3 (interpersonal concordance orientation), actions that are helpful or please others are considered “good.” Gaining approval (being a “good boy” or “nice girl”) is an important motivator. Faced with the Heinz dilemma, the adolescent might suggest that because society says a husband must take care of his wife, Heinz should steal the drugs so that others won’t think poorly of him. In Stage 4 (law and order orientation), the focus is on rules and social order. Duty and obedience to authorities define what is right. Heinz should not steal because stealing is against the law. Cheating on exams is not right because one is obligated to uphold a student code of conduct (Kohlberg & Hersh, 1977).

postconventional moral reasoning Kohlberg’s stage of moral development in which right and wrong are determined by the individual’s beliefs about morality, which sometimes do not coincide with society’s rules and regulations.

339

POSTCONVENTIONAL MORAL REASONING The third level of Kohlberg’s theory is postconventional moral reasoning. Right and wrong are determined by the individual’s beliefs about morality, which may be inconsistent with society’s rules and regulations. Stage 5 (social contract, legalistic orientation) reasoning suggests that laws should be followed when they are upheld by society as a whole; but, if a law does not exhibit “social utility,” it should be changed to meet the needs of society. In other words, a law-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed the importance of collecting data from a representative sample, whose members’ characteristics closely reflect the population of interest. Kohlberg’s early research included only male participants, but he and others generalized his findings to females. Generalizing from an all-

CRITICISMS Kohlberg’s theory of moral development has not been without criticism. Carol Gilligan (1982) leveled a number of serious critiques, suggesting that the theory did not represent women’s moral reasoning. She noted that Kohlberg’s initial studies included only male participants, introducing bias into his research findings. Gilligan suggested that Kohlberg had discounted the importance of caring and responsibility and that his choice of an all-

Gender Development

LO 16 Define gender and explain how culture plays a role in its development.

gender The dimension of masculinity and femininity based on social, cultural, and psychological characteristics.

gender identity The feeling or sense of being either male or female, and compatibility, contentment, and conformity with one’s gender.

One important developmental process, which can unfold at any point in life but often occurs during childhood and adolescence, is the establishment of gender identity. Gender refers to the dimension of masculinity and femininity based on social, cultural, and psychological characteristics. Men are typically perceived as masculine, and women are assumed to be feminine. But concepts of masculine and feminine vary according to culture, social context, and the individual. According to the American Psychiatric Association (2013), “gender” also indicates the public and often legally recognized role a person has as a man or woman, boy or girl. Gender identity is the feeling or sense of being either male or female, and compatibility, contentment, and conformity with one’s gender (Egan & Perry, 2001; Tobin et al., 2010).

gender roles The collection of actions, beliefs, and characteristics that a culture associates with masculinity and femininity.

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we described how learning can occur by observing and imitating a model. Here we see how this type of learning can shape the formation of gender roles.

LEARNING GENDER ROLES We learn how to behave in gender-

The social-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 5, we discussed operant conditioning, which is learning that results from consequences. Here, the positive reinforcer is encouragement, which leads to an increase in a desired behavior. The punishment is discouragement, which reduces the unwanted behavior.

340

Gender roles are also established through operant conditioning. Children often receive reinforcement for behaviors considered gender-

Keep in mind that not all parents and caregivers are passionate about preserving traditional gender roles. Researchers have found that children develop more fluid ideas about gender-

gender schemas The psychological or mental guidelines that dictate how to be masculine and feminine.

Toronto parents Kathy Witterick and David Stocker decided to raise their third child gender free. When baby Storm was born, Witterick and Stocker informed family and friends that the sex of the child would remain a secret for some time; they wanted Storm to make his or her own decision about gender identity (Poisson, 2011, December 26). Pictured here is Storm with big brother Jazz.

COGNITION AND GENDER SCHEMAS Children also seem to develop gender roles by actively processing information (Bem, 1981). In other words, kids think about the behaviors they observe, including the differences between males and females. They watch their parents’ behavior, often following suit (Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2002). Using the information they have gathered, they develop a variety of gender-

BIOLOGY AND GENDER Clearly, culture and learning influence the development of gender-

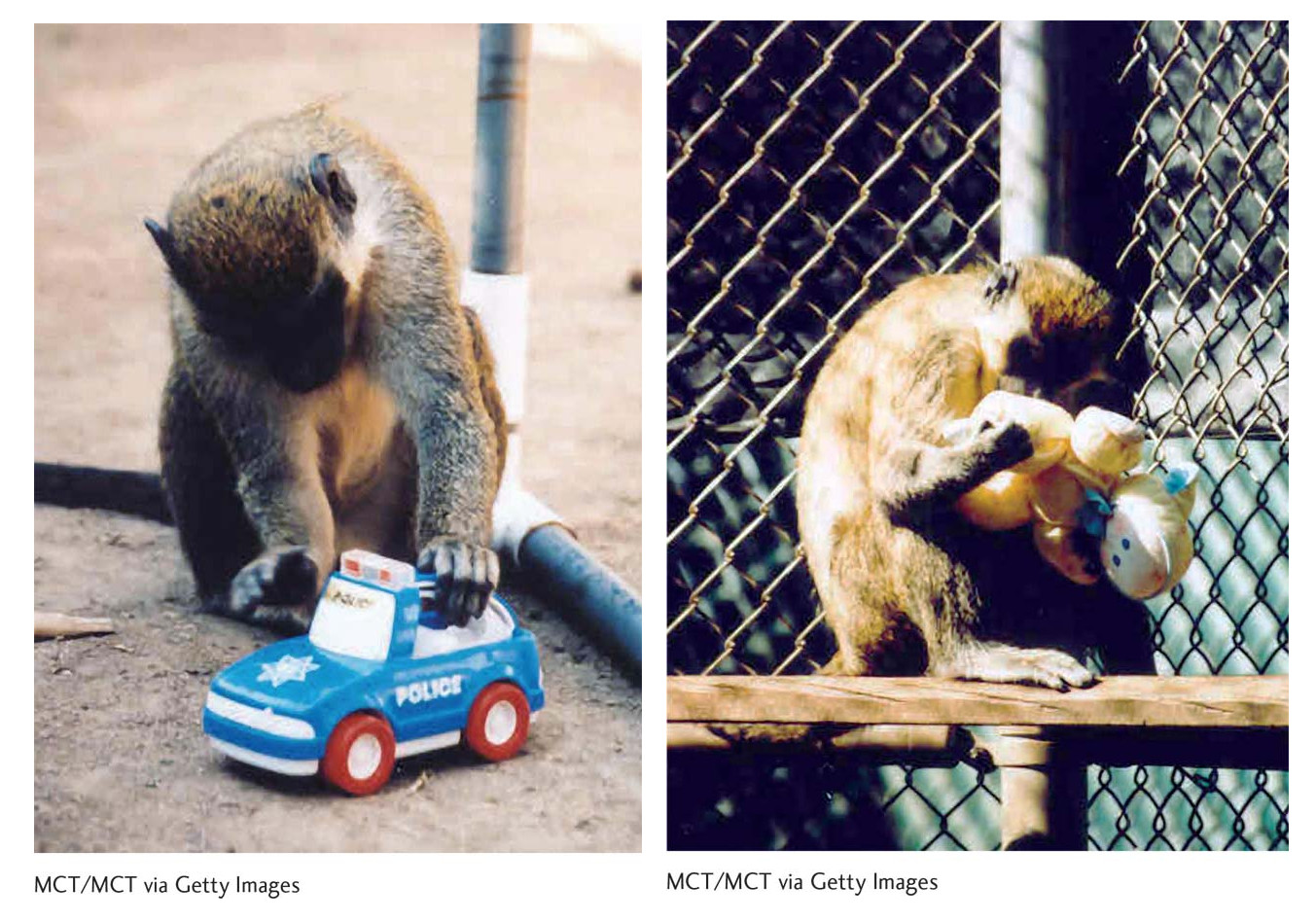

A male vervet monkey rolls a toy car on the ground (left), and a female examines a doll (right). When provided with a variety of toys, male vervet monkeys spend more time playing with cars and balls, whereas females are drawn to dolls and pots (Alexander & Hines, 2002). Similar behaviors have been observed in rhesus monkeys (Hassett, Siebert, & Wallen, 2008). These studies suggest a biological basis for the gender-

341

Nature and Nurture

The Case of Bruce Reimer

Bruce Reimer and his twin brother were born in 1965. During a circumcision operation at 8 months, Bruce’s penis was almost entirely burnt away by electrical equipment used in the procedure. When he was about 2 years old, his parents took the advice of Johns Hopkins psychologist John Money and decided to raise Bruce as a girl (British Broadcasting Corporation [BBC], 2014, September 17). The thinking at the time was that what made a person a male or female was not necessarily the original structure of the genitals, but rather how he or she was raised (Diamond, 2004).

Bruce Reimer and his twin brother were born in 1965. During a circumcision operation at 8 months, Bruce’s penis was almost entirely burnt away by electrical equipment used in the procedure. When he was about 2 years old, his parents took the advice of Johns Hopkins psychologist John Money and decided to raise Bruce as a girl (British Broadcasting Corporation [BBC], 2014, September 17). The thinking at the time was that what made a person a male or female was not necessarily the original structure of the genitals, but rather how he or she was raised (Diamond, 2004).

Just before Bruce’s second birthday, doctors removed his testicles and used the tissues to create the beginnings of female genitalia. His parents began calling him Brenda, dressing him like a girl and encouraging him to engage in stereotypically “girl” activities such as baking and playing with dolls (BBC, 2014, September 17). But Brenda did not adjust so well to her new gender assignment. An outcast at school, she was called cruel names like “caveman” and “gorilla.” She brawled with both boys and girls alike, and eventually got kicked out of school (Diamond & Sigmundson, 1997).

HIS PARENTS. . . . DECIDED TO RAISE BRUCE AS A GIRL.

When Brenda hit puberty, the problem became even worse. Despite ongoing psychiatric therapy and estrogen replacement, she could not deny what was in her nature—

At age 14, Brenda decided to “reassign himself” to be a male. He then changed his name to David, began taking male hormones, and underwent a series of penis construction surgeries (Colapinto, 2000; Diamond & Sigmundson, 1997). At 25, David married and adopted his wife’s children, and for some time it appeared he was doing quite well (Diamond & Sigmundson, 1997). But sadly, at the age of 38, he took his own life.

We are in no position to explain the tragic death of David Reimer, but we cannot help but wonder what role his traumatic gender reassignment might have played. Keep in mind that this is just an isolated case. As discussed in Chapter 1, we should be extremely cautious about making generalizations from case studies, which may or may not be representative of the larger population. Many people who undergo sex reassignment go on to live happy and fulfilling lives.

GENDER-

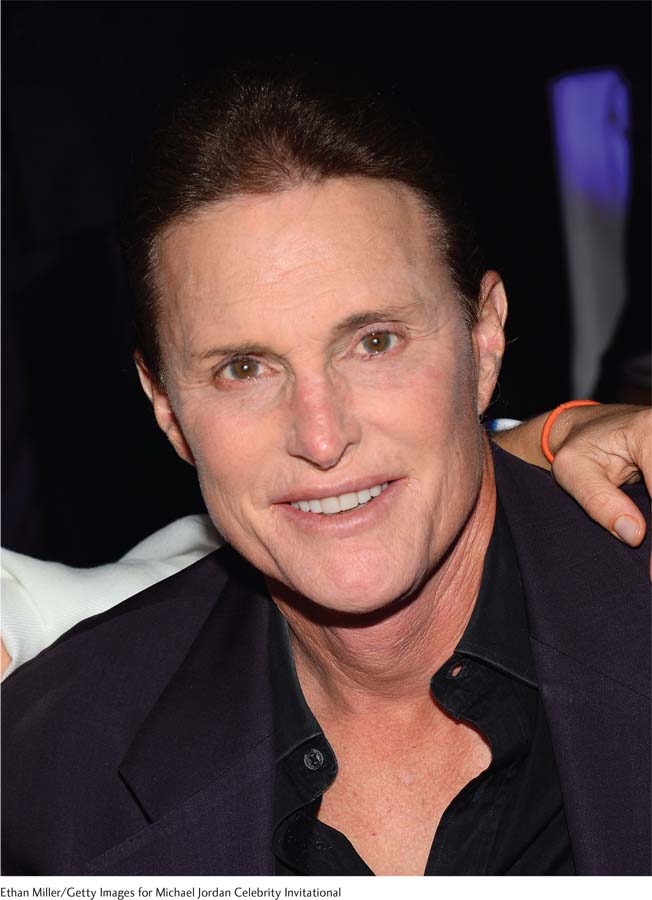

In April 2015, former Olympian and reality TV personality Bruce Jenner announced he would be making a transition from male to female (Steel, 2015, April 25). There is a lot of inconsistency in the terminology and labels associated with trans, that is, those who are transgender, transsexual, or nonconforming to traditional gender identities. Thus, we should be sensitive about labeling and, when possible, ask trans people how they would like to be identified (Hendricks & Testa, 2012, October).

Children, especially boys, tend to cling to gender-

androgyny The tendency to cross gender-

American Idol sensation Adam Lambert reportedly embraces androgyny, the mixing of stereotypically male and female qualities. “I’m trying to make it current again,” Lambert told the Daily Xtra. “I’ve always been attracted to that” (Thomas, December 30, 2009).

342

ANDROGYNY Those who cross gender-

transgender Refers to people whose gender identity and expression do not typically match the gender assigned to them at birth.

TRANSGENDER AND TRANSSEXUAL At birth, most people are identified as male or female; this is referred to as an infant’s natal gender, or gender assignment. When natal gender does not feel right, an individual may have transgender experiences. According to the American Psychological Association, transgender refers to people “whose gender identity,gender expression, or behavior does not conform to that typically associated with the sex to which they were assigned at birth” (APA, 2011a, p. 1). Remember that gender identity is the feeling or sense of being either male or female. For a person who is transgender, a mismatch occurs between that sense of identity and the gender assignment at birth. This disparity can be temporary or persistent (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Approximately 700,000 individuals in the United States (around 0.2% of the population) consider themselves to be transgender (Gates, 2011).

transsexual An individual who seeks or undergoes a social transition to the other gender, and who may make changes to his or her body through surgery and medical treatment.

When the discrepancy between natal gender and gender identity leads to significant experiences and/or expression of distress, an individual might meet the criteria for a gender dysphoria diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some transgender individuals try to resolve this discontent through medical intervention. According to the American Psychiatric Association, a person is considered transsexual if he or she seeks or undergoes “a social transition from male to female or female to male, which in many, but not all, cases also involve[s] a somatic transition by cross-

Emerging Adulthood

Childhood and adolescence pave the way for the stage of life known as adulthood. In the United States, the legal age of adulthood is 18 for some activities (voting, military enlistment) and 21 for others (drinking, financial responsibilities). These ages are not consistent across cultures and countries (the legal drinking age in some nations is as young as 16). Many cultures and religions mark the transition into adulthood by ceremonies and rituals (for example, Jewish bar/bat mitzvahs, Australian walkabouts, Christian confirmations, Latin American quinceañeras), starting as early as age 12.

emerging adulthood A phase of life between 18 and 25 years that includes exploration and opportunity.

343

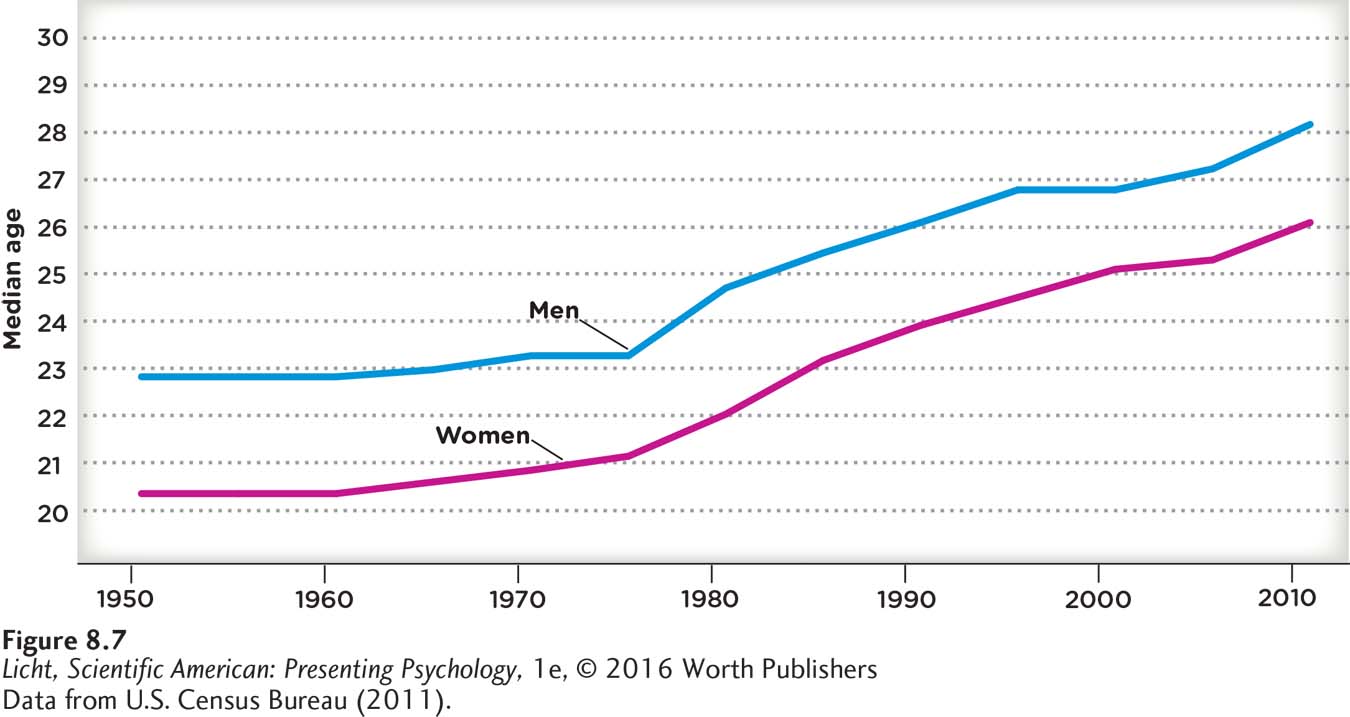

Complicating the demarcation between adolescence and adulthood is the fact that young people in today’s Western societies are marrying much later (Arnett, 2000; Elliott, Krivickas, Brault, & Kreider, 2012), and remaining dependent on their families for longer periods of time (Figure 8.7). Psychologists now propose a phase known as emerging adulthood, which is the time of life between 18 and 25 years of age. Emerging adulthood is neither adolescence nor early adulthood, and it is a period of exploration and opportunity. The emerging adult has neither the permanent responsibilities of adulthood nor the dependency of adolescence. By this time, most adolescent egocentrism has disappeared, which is apparent in intimate relationships and empathy (Elkind, 1967). During this stage, one can seek out loving relationships, education, and new views of the world before settling into the relative permanency of family and career (Arnett, 2000).

Many developmental psychologists consider marriage a marker of adulthood because it can represent the first time a person leaves the family home to set out on his or her own. Since the 1950s and 1960s, the median age at which men and women marry for the first time has increased, a trend that appears likely to continue.

show what you know

Question 1

1. The physical features not associated with reproduction, but that become more distinct during adolescence, are known as

primary sex characteristics.

secondary sex characteristics.

menarche.

puberty.

b. secondary sex characteristics.

Question 2

2. Your cousin is almost 14, and she has begun to use deductive reasoning to draw conclusions and critical thinking to support her arguments. Her cognitive development is occurring in Piaget’s

formal operational stage.

concrete operational stage.

ego identity versus role confusion stage.

instrumental–

relativist orientation.

a. formal operational stage.

Question 3

3. _________ moral reasoning usually is seen in young children, and it focuses on the consequences of behaviors, both good and bad.

Preconventional

Question 4

4. “Helicopter” parents pave the way for their children, troubleshooting problems for them, and making sure they are successful in every endeavor. How might this type of parenting impact an adolescent in terms of Erikson’s stage of ego identity versus role confusion?

Answers will vary. During the stage of ego identity versus role confusion, an adolescent seeks to define himself through his values, beliefs, and goals. If a helicopter parent has been troubleshooting all of her child’s problems, the child has never had to learn to take care of things for himself. Thus, he may feel helpless and unsure of how to handle a problem that arises. The parent might also have ensured the child was successful in every endeavor, but this too could cause the child to be unable to identify his true strengths, again interfering with the creation of an adult identity.