9.2 Back to Basics: Hunger

A Somali woman hauls a bag of food aid through the massive Dadaab refugee settlement in Kenya. When famine struck the Horn of Africa in 2011, tens of thousands of Somalis fled their homeland and resettled in overcrowded refugee camps like Dadaab (Gettleman, 2011, July 15).

STARVING IN SOMALIA Like many Somali Americans, Mohamed regularly sends money back home to relatives in need. Without assistance from family members living in more prosperous countries like the United States, many Somalis would not be able to afford food, medicine, and other necessities. As Mohamed says, “You can’t just leave your family back home to starve.”

STARVING IN SOMALIA Like many Somali Americans, Mohamed regularly sends money back home to relatives in need. Without assistance from family members living in more prosperous countries like the United States, many Somalis would not be able to afford food, medicine, and other necessities. As Mohamed says, “You can’t just leave your family back home to starve.”

In the spring of 2011, the Horn of Africa was hit by a drought that plunged Somalia into one of the greatest humanitarian crises of our time—

369

In the coming pages, we will explore hunger, one of the most powerful motivators of human behavior. You will learn what happens in the brain and body when a person is in dire need of food, either because of external circumstances (a famine) or deep-

Hungry Brain, Hungry Body

It’s midnight; you are struggling to get through the final pages of your psychology chapter. Suddenly, your stomach lets out a desperate gurgling cry. “Feed me!” Time to heat up that frozen burrito, you say to yourself as you head into the kitchen. But wait! Are you really hungry?

LO 7 Discuss how the stomach and the hypothalamus make us feel hunger.

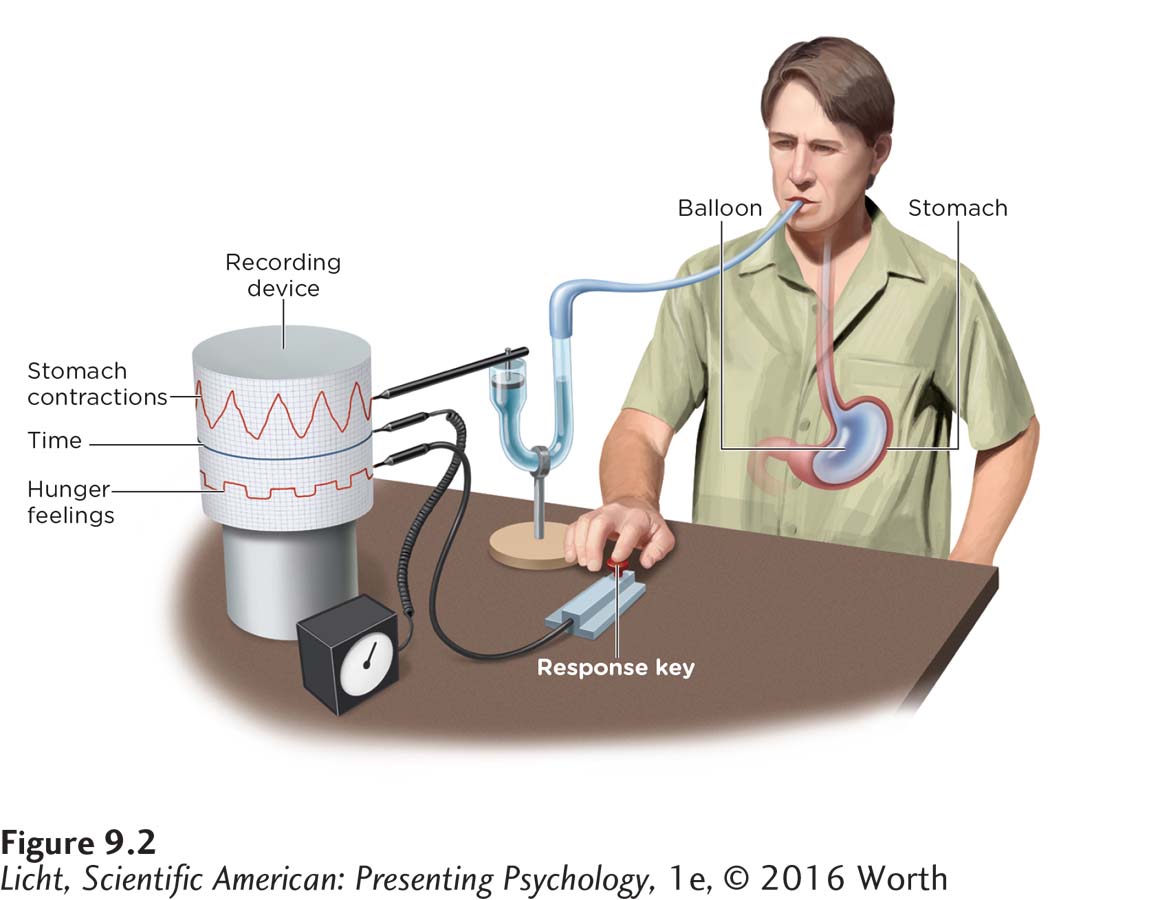

Washburn swallowed a special balloon attached to a device designed to monitor stomach contractions. While the balloon was in place, he pressed a key every time he felt hungry. Comparing the record of key presses against the balloon measurements, Washburn was able to show that stomach contractions accompany feelings of hunger.

THE STOMACH AND HUNGER In a classic study, Walter Cannon and A. L. Washburn (1912) sought to answer this question (well, not this exact question, but they did want to learn what causes stomach contractions). Here’s a brief synopsis of the experiment: To help monitor and record his stomach contractions, Washburn swallowed a balloon that the researchers could inflate. The researchers also kept track of Washburn’s hunger levels, having him push a button anytime he felt “hunger pangs” (Figure 9.2). What did the experiment reveal? Anytime he felt hunger, his stomach contracted.

BLOOD CHEMISTRY AND HUNGER Cannon and Washburn’s experiment demonstrates that the stomach plays an important role in hunger, but it’s just one piece of the puzzle. One reason we know this is that cancer patients who have had their stomachs surgically removed do not differ from people with their stomachs intact in regard to feelings of satiety (that is, feeling full) or the amount of food eaten during a meal (Bergh, Sjöstedt, Hellers, Zandian, & Södersten, 2003). We also must consider the chemicals in the blood, such as glucose, or blood sugar. When glucose levels dip, the stomach and liver send signals to the brain that something must be done about this reduced energy situation. The brain, in turn, will initiate a sense of hunger.

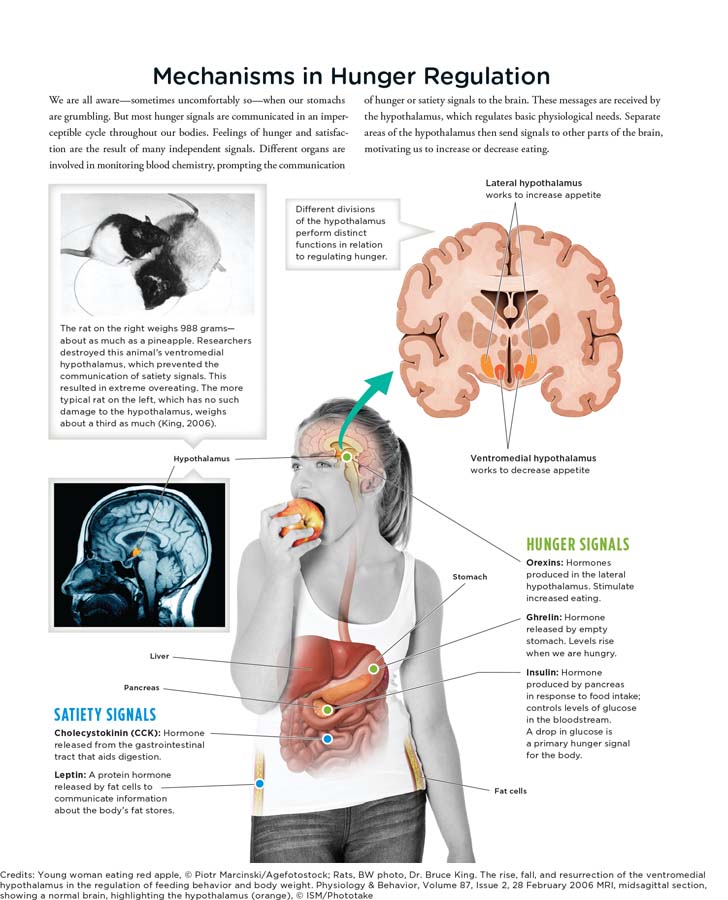

THE HYPOTHALAMUS AND HUNGER One part of the brain that helps regulate hungry feelings is the hypothalamus, which can be divided into functionally distinct areas. When the lateral hypothalamus is activated, appetite increases. This occurs even in well-

370

If the ventromedial hypothalamus becomes activated, appetite declines, causing an animal to stop eating. Disable this region of the brain, and the animal will overeat to the point of obesity. The ventromedial hypothalamus receives information about levels of blood glucose and other feeding-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 2, we described hormones as chemical messengers released in the bloodstream. Hormones do not act as quickly as neurotransmitters, but their messages are more widely spread throughout the body. Here, we see how hormones are involved in communicating information about hunger and feeding behaviors.

The hypothalamus has a variety of sensors that react to information about appetite and food intake. Once this input is processed, appropriate responses are communicated via hormones in the bloodstream (Infographic 9.2). One such hormone is leptin, a protein emitted by fat cells that plays a role in suppressing hunger. Another is insulin, a pancreatic hormone involved in controlling levels of glucose in the bloodstream. With input from these and other hormones, the brain can monitor energy levels and respond accordingly. This complex system enables us to know when we are hungry, full, or somewhere in between.

371

INFOGRAPHIC 9.2

Let’s Have a Meal: Cultural and Social Context

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 1, we discussed naturalistic observation, a form of descriptive research that studies participants in their natural environments. One important feature of this type of study is that researchers do not disturb participants or their environment. Here, we assume the researchers were able to measure and record the meals chosen without interfering in the participants’ natural behaviors.

Biology is not the only factor influencing eating habits. We must also consider the culture and social context in which we eat. In the United States, most of our social activities, holidays, and work events revolve around food. We may not even be hungry, but when presented with a spread of food, we find ourselves eating. All too often we eat too fast, rushing to our next event, class, or meeting, not taking the time to experience the sensation of taste. We tend to match our food intake to those around us, although we may not be aware of their influence (Herman, Roth, & Polivy, 2003; Howland, Hunger, & Mann, 2012). Gender plays a role in eating habits as well. Using naturalistic observation, researchers found that women choose lower-

PORTION DISTORTION A variety of factors drive our decisions to begin or stop eating, including hunger, satiety, and food taste (Vartanian, Herman, & Wansink, 2008). But more subtle variables, such as portion size, come into play too. In one study, participants at a movie theater were given free popcorn, some in medium-

Portion size is just one factor influencing food intake. Visual cues are also important, especially when they provide feedback about how much you have eaten. To study this, researchers gave college students tubes of potato chips to eat while watching a movie. In some of the tubes, every 7th chip was dyed red. Participants given tubes with the occasional red chips consumed 50% less than those given tubes with no red chips. Thus we see, interrupting mindless eating (Wait a second, that’s a red chip) can decrease the amount of food consumed in one sitting (Geier, Wansink, & Rozin, 2012).

Obesity

In today’s world, a growing number of people are struggling with obesity, fueling popular interest in strategies for cutting down food intake. Two-

372

set point The stable weight that is maintained despite variability in exercise and food intake.

SET POINT, SETTLING POINT, AND HEREDITY Surprisingly, there is relatively little fluctuation in adult weight over time. The communication between the brain and the appetite hormones help regulate the body’s set point, or stable weight that we tend to maintain despite variability in day-

More than a third of U.S. adults are obese, meaning they have a body mass index (BMI) greater than or equal to 30 (Ogden et al., 2014). Obesity has become a worldwide phenomenon, affecting countries as far-

CONNECTIONS

In Chapter 7, we presented heritability, the degree to which heredity is responsible for a particular characteristic in a population. The heritability for BMI is 65%, indicating that around 65% of the variation in BMI can be attributed to genes, and 35% to environmental influences.

Some critics of the set point model suggest that it fails to appreciate the importance of social and environmental influences (Stroebe, van Koningsbruggen, Papies, & Aarts, 2013). These theorists suggest we should consider a settling point, which is less rigid and can explain how the “set” point can actually change based on the relative amounts of food consumed and energy used. A settling point can help us understand how body weight may shift to a newly maintained weight, and why so many people are overweight as a result of environmental factors, such as bigger meal portions, calorie-

OVEREATING, SLEEP, AND SCREEN TIME As you well know, deciding what and when to eat does not always come down to being hungry or full. We must consider how motivation plays a role in our eating patterns. Some people eat not because they are hungry, but because they are bored, sad, or anxious. Others eat simply because the clock indicates that it is mealtime. Higher brain regions involved in eating decisions can override the hypothalamus, driving you to devour that cheesy burrito even when you don’t need the calories.

If our set point helps us maintain a certain weight, how does this impact people who struggle with obesity? Obesity is both a physiological and psychological issue. There is some evidence that genes play a role, and we also know some illnesses can lead to obesity (Anis et al., 2010; Plomin et al., 2013). But one often overlooked lifestyle factor related to obesity is sleep. Preliminary research suggests that inadequate sleep is linked to weight problems (a negative correlation between sleep and weight gain). In contrast, individuals who sleep between 6 and 8 hours are more likely to lose weight. Additionally, a positive correlation exists between screen time and weight gain: the more screen time, the more weight gain. When screen time interferes with making healthy eating choices and getting regular physical exercise, weight loss is not as successful (Elder et al., 2012).

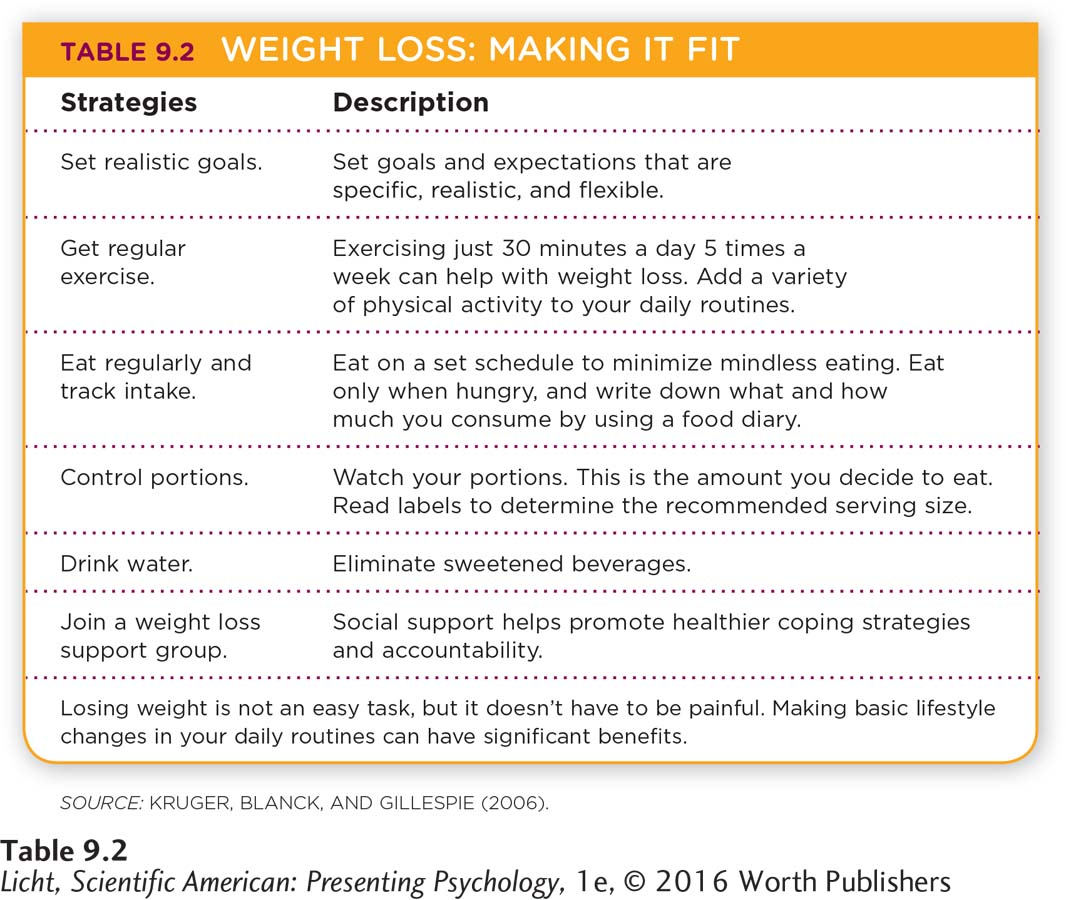

To lose weight, one must eat less and move more (Table 9.2); in other words, use more calories than you are taking in. Our ancestors didn’t have to worry about this. They had to choose foods rich in calories to give them energy to sustain themselves. Although this was a very efficient means of survival for them, it doesn’t work out so well for us. When experiencing a “famine” (decrease in the caloric intake our bodies are accustomed to), our metabolism naturally slows down, requiring fewer calories and making it harder to lose weight.

Apply This

In response to the obesity problem in the United States, policies have been implemented to raise awareness and discourage overeating. One such intervention is requiring information about calories to be clearly labeled, which can serve as a visual cue or reminder. Providing this information can impact healthy food choices. However, accessibility to comparably priced healthy alternatives must be increased (in vending machines, for example)—but this too may require changes in policy (Stroebe et al., 2013).

Eating Disorders

373

LO 8 Outline the characteristics of the major eating disorders.

Although many people deal with obesity, others struggle with food in a different way. Eating disorders are serious dysfunctions in eating behavior that can involve restricting food consumption, obsessing over weight or body shape, eating too much, and purging (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Eating disorders usually begin in the early teens and typically affect girls. That doesn’t mean boys do not struggle with eating disorders; 1 in 4 children ages 5–

anorexia nervosa An eating disorder identified by significant weight loss, an intense fear of being overweight, a false sense of body image, and a refusal to eat the proper amount of calories to achieve a healthy weight.

A British jockey weighs in at a horse racetrack near Manchester, England. Jockeys must satisfy strict weight requirements in order to ride in races. For many competitions, this means weighing 110 pounds or less. In an effort to stay thin, jockeys have been known to restrict their intake of food and liquid, sweat off water weight in saunas, and force themselves to vomit (Associated Press, 2008, April 25; McKenzie, 2012, October 23).

ANOREXIA NERVOSA One of the most commonly known eating disorders is anorexia nervosa, which is characterized by self-

374

bulimia nervosa An eating disorder characterized by extreme overeating followed by purging, with serious health risks.

BULIMIA NERVOSA Another eating disorder is bulimia nervosa, which involves recurrent episodes of binge eating, or consuming a large amount of food in a short period of time (with that amount being greater than most people would eat in the same time frame). While bingeing, the person feels a lack of control and thus engages in purging behaviors to prevent weight gain—

binge-

BINGE-

We know that eating disorders are apparent in America—

across the WORLD

Admiration for thin body types is becoming more prevalent across cultures. Anorexia nervosa has been documented in both the Western and non-

A Cross-

Close your eyes and imagine the stereotypical beauty queen. Is she curvy like a Coke bottle or long and lean like a Barbie doll? We suspect the image that popped into your mind’s eye looked more like the famed plastic doll. Let’s face it: Western concepts of beauty, particularly female beauty, often go hand-

Close your eyes and imagine the stereotypical beauty queen. Is she curvy like a Coke bottle or long and lean like a Barbie doll? We suspect the image that popped into your mind’s eye looked more like the famed plastic doll. Let’s face it: Western concepts of beauty, particularly female beauty, often go hand-

With all this pressure to be slender, it’s no wonder eating disorders like anorexia and bulimia are most commonly diagnosed and treated in Western societies such as the United States (Keel & Klump, 2003; Littlewood, 2004). Psychologists once believed eating disorders only occurred in regions of the world influenced by Western culture. Anorexia and bulimia were thought to be psychological disorders unique to certain societies. But evidence suggests it is not that simple.

THEY . . . FOUND EVIDENCE OF PEOPLE, PARTICULARLY YOUNG WOMEN, STARVING THEMSELVES SINCE MEDIEVAL TIMES. . . .

Keel and Klump (2003) conducted a large review of studies and concluded that anorexia occurs throughout the non-

375

However, Keel and Klump (2003) found no evidence of bulimia (based on strict criteria) existing in regions isolated from Western culture. They also determined that the prevalence of the disorder dramatically increased during the second half of the 1900s, just as the fixation with thin was beginning to take hold. This pattern might not be as strong outside of Western culture, but such a focus on body image is becoming more prevalent across the world.

show what you know

Question 1

1. Washburn swallowed a special balloon to record his stomach contractions. He also pressed a button to record his feelings of hunger. The findings indicated that whenever he felt hunger, his

stomach was contracting.

stomach was still.

blood sugar went up.

ventromedial hypothalamus was active.

a. stomach was contracting.

Question 2

2. Bulimia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by

restrictions of energy intake.

extreme fear of gaining weight, although one’s body weight is extremely low.

a distorted sense of body weight and figure.

extreme overeating followed by purging.

d. extreme overeating followed by purging.

Question 3

3. Describe how the hypothalamus triggers hunger and influences eating behaviors.

When glucose levels dip, the stomach and liver send signals to the brain that something must be done about this reduced energy source. The brain, in turn, initiates a sense of hunger. Signals from the digestive system are sent to the hypothalamus, which then transmits signals to higher regions of the brain. When the lateral hypothalamus is activated, appetite increases. On the other hand, if the ventromedial hypothalamus becomes activated, appetite declines, causing an animal to stop eating.