424

Attachment to Others and Development of Self

425

- The Caregiver–Child Attachment Relationship

- Attachment Theory

- Measurement of Attachment Security in Infancy

- Box 11.1: Individual Differences Parental Attachment Status

- Cultural Variations in Attachment

- Factors Associated with the Security of Children’s Attachment

- Box 11.2: Applications Interventions and Attachment

- Does Security of Attachment Have Long-Term Effects?

- Review

- Conceptions of the Self

- The Development of Conceptions of Self

- Identity in Adolescence

- Review

- Ethnic Identity

- Ethnic Identity in Childhood

- Ethnic Identity in Adolescence

- Review

- Sexual Identity or Orientation

- The Origins of Youths’ Sexual Identity

- Sexual Identity in Sexual-Minority Youth

- Review

- Self-Esteem

- Sources of Self-Esteem

- Self-Esteem in Minority Children

- Culture and Self-Esteem

- Review

- Chapter Summary

426

Themes

Nature and Nurture

Nature and Nurture

The Active Child

The Active Child

The Sociocultural Context

The Sociocultural Context

Individual Differences

Individual Differences

Research and Children’s Welfare

Research and Children’s Welfare

Between 1937 and 1943, numerous child-care professionals in both the United States and Europe reported instances of a disturbing phenomenon: children who seemed to have no concern or feeling for anyone but themselves. Some of the children were withdrawn and isolated; others were overactive and abusive toward their peers. By the time they were adolescents, these children often had histories of persistent stealing, violence, and sexual misdemeanors. Many of these children had been reared in institutions in which they received adequate physical care but experienced little social interaction; others had been shifted from foster home to foster home in infancy and early childhood (Bowlby, 1953).

At about the same time, similar disturbances were being observed among children who had been orphaned or separated from their parents during World War II and were in refugee camps or other institutional settings. John Bowlby, an English psychoanalyst who worked with many of these children, reported that they were very listless, depressed or otherwise emotionally disturbed, and mentally stunted. Older refugee children often seemed to have lost all interest in life and were possessed by feelings of emptiness (Bowlby, 1953). These children, like the Romanian orphans discussed in Chapter 1 tended not to develop normal emotional attachments with other people.

On the basis of such observations, René Spitz, a French psychoanalyst who had worked with Freud, conducted a series of classic studies of how the lack of adequate caregiving affects development (Spitz, 1945, 1946, 1949). Spitz filmed infants (a methodological innovation) residing in orphanages, most of whom had been born to unmarried mothers and had been given up for adoption. The films were extremely poignant and painful to watch. They documented the fact that, despite receiving good institutional care, the infants were generally sickly and developmentally impaired. In many cases, the infants seemed unmotivated to live: their death rate was about 37% over 2 years’ time, compared with no deaths in an institution where children had daily contact with their mothers. The films’ most important contribution, however, was their evidence of intense and prolonged grief and depression in infants who had been separated from their mothers after developing a loving relationship with them. Psychologists of the time did not believe that infants could experience such emotions (Emde, 1994).

Taken together, these early observations also challenged the more central belief, then held by many child-care professionals, that if children in institutions such as orphanages received good physical care, including proper nourishment and health care, they would develop normally. These professionals placed little emphasis on the emotional dimensions of caregiving. As a result of the studies of children who lost their parents in the 1940s, it became generally recognized that, no matter how hygienic and competently managed, institutions like orphanages put babies at high risk because they did not provide the kind of caregiving that enables infants to form close socioemotional bonds. Adoption—the earlier the better—came to be viewed as a far better option.

Another important outcome of the work of Bowlby and others who studied institutionalized children was the beginning of systematic research on how the quality of parent–child interactions affects children’s development in families, especially their development of emotional attachments to other people. This research, which continues today, has led to a much deeper understanding of the ways in which the early parent–child emotional bond likely influences children’s interactions with others from infancy into adulthood. It has also provided new insight into the development of children’s sense of self, as well as of their emotions, including their feelings of self-worth.

427

attachment an emotional bond with a specific person that is enduring across space and time. Usually, attachments are discussed in regard to the relation between infants and specific caregivers, although they can also occur in adulthood.

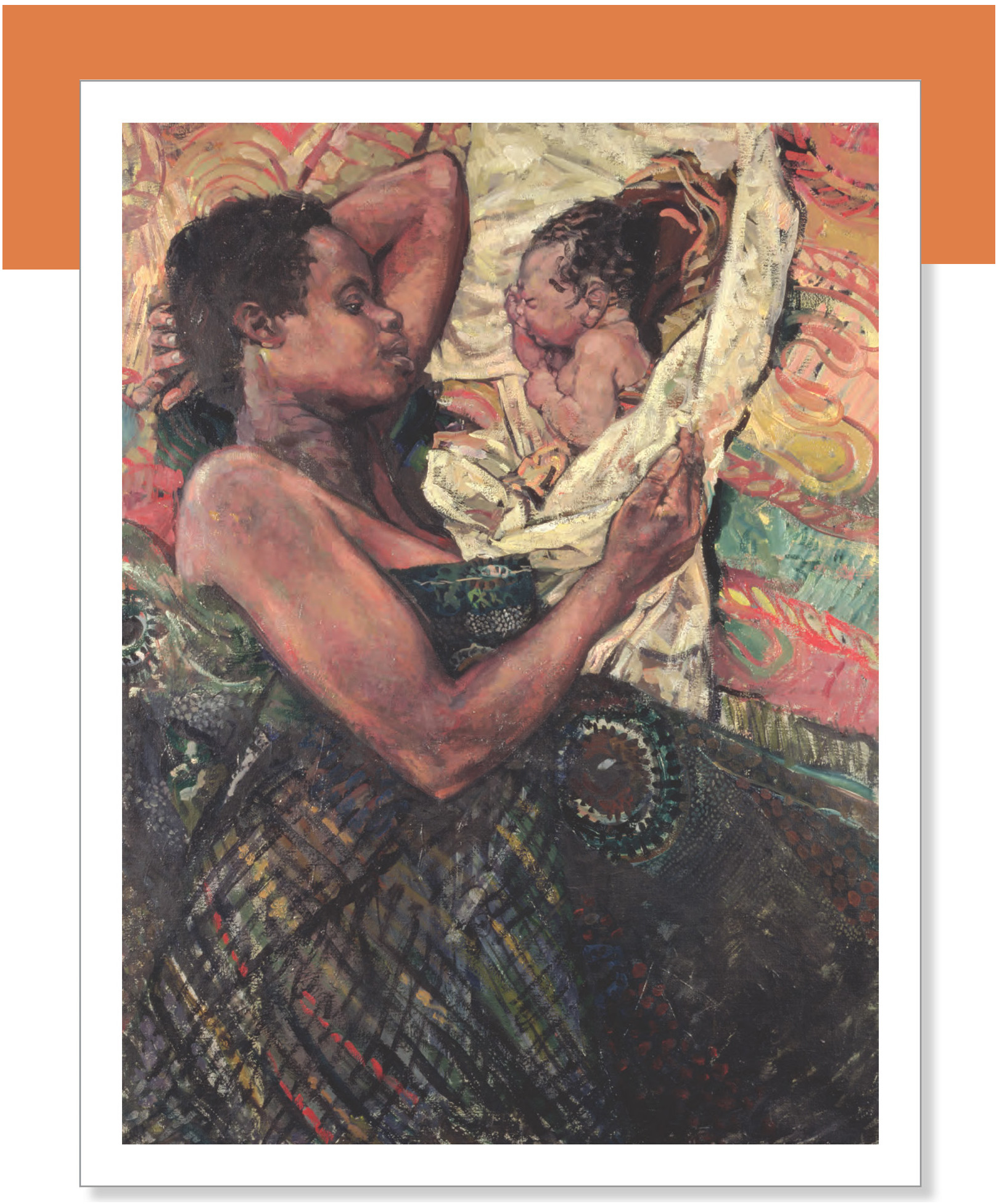

In this chapter, we will first explore how children develop attachments, close and enduring emotional bonds to parents or other primary caregivers. Then we will examine the ways in which the nature of these attachments to others seems to set the stage for the child’s near- and long-term development. As you will see, the attachment process appears to be biologically based yet unfolds in different ways, depending on the familial and cultural context. Thus, the themes of nature and nurture and the sociocultural context will be important in our discussion of this topic. You will also see that although most children in normal social circumstances develop attachments to their parents, the quality of these attachments differs in important ways and has implications for each child’s social and emotional development. The theme of individual differences will therefore figure prominently in our discussion as well. The theme of research and children’s welfare is also relevant to our examination of experimental interventions designed to enhance the quality of mother–child attachment.

Next we will examine a related issue—the development of children’s sense of self, that is, their self-understanding, self-identity, and self-esteem. Although many factors influence these areas of development, the quality of children’s early attachments lays the foundation for how children feel about themselves, including their sense of security and well-being. Over time, children’s self-understanding, self-esteem, and self-identity are also shaped by how others perceive and treat them, by biologically based characteristics of the child, and by children’s developing abilities to think about and interpret their social worlds. Thus, the themes of nature and nurture, individual differences, the sociocultural context, and the active child will be evident in our discussion of the development of self.