The Caregiver–Child Attachment Relationship

Following the very disturbing observations made in the 1930s and 1940s regarding children separated from their parents early in life, researchers began to conduct systematic studies of this phenomenon. Much of the early research, such as that conducted by Spitz, focused on how the development of young children who had been orphaned or otherwise separated from their parents was affected by the quality of the caregiving they subsequently received. The research on children adopted from Romania (discussed in Chapter 1) is probably the best known of recent studies on this topic, all of which support the idea that institutional care in the first years of life typically hinders optimal social, emotional, and cognitive development (McCall et al., 2011; Rutter et al., 2010).

Another line of research in this area involved experimental work with monkeys. In some of the most famous research in psychology, Harry Harlow and his colleagues (Harlow & Harlow, 1965; Harlow & Zimmerman, 1959; E. E. Nelson, Herman, et al., 2009; L. D. Young et al., 1973) reared infant rhesus monkeys in isolation from birth, comparing their development with that of monkeys reared normally with their mothers. The isolated babies were well fed and kept healthy, but they had no exposure to their mother or other monkeys. When they finally were placed with other monkeys 6 months later, they compulsively bit and rocked themselves and avoided other monkeys completely, apparently incapable of communicating with, or learning from, others. They also showed high levels of fear when exposed to threatening stimuli such as a loud sound. As adults, formerly isolated females had no interest in sex. If they were artificially impregnated, they did not know what to do with their babies. At best, they tended to ignore or reject them; at worst, they attacked them. This research, although examining the effects of the lack of all early social interaction (and not just that with parents), strongly supported the view that children’s healthy social and emotional development is rooted in their early social interactions with adults.

428

Attachment Theory

attachment theory theory based on John Bowlby’s work that posits that children are biologically predisposed to develop attachments to caregivers as a means of increasing the chances of their own survival

The findings from observations of children and monkeys separated from their parents were so dramatic that psychiatrists and psychologists were compelled to rethink their ideas about early development. Foremost in this effort were John Bowlby, who proposed attachment theory, and his colleague, Mary Ainsworth, who extended and tested Bowlby’s ideas.

Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

secure base refers to the idea that the presence of a trusted caregiver provides an infant or toddler with a sense of security that makes it possible for the child to explore the environment

Bowlby’s theory of attachment was strongly influenced by several key tenets of Freud’s theories, especially the idea that infants’ earliest relationships with their mothers shape their later development. However, Bowlby replaced the psychoanalytic notion of a “needy, dependent infant” with the idea of a “competence-motivated infant” who uses his or her primary caregiver as a secure base (E. Waters & Cummings, 2000). The general idea of the secure base is that the presence of a trusted caregiver provides the infant or toddler with a sense of security that allows the child to explore the environment and hence to become generally knowledgeable and competent. In addition, the primary caregiver serves as a haven of safety when the infant feels threatened or insecure, and the child derives comfort and pleasure from being near the caregiver.

Bowlby’s idea of the primary caregiver as a secure base was directly influenced by ethological theories, particularly the ideas of Konrad Lorenz (see Chapter 9). Bowlby proposed that the attachment process between infant and caregiver is rooted in evolution and increases the infant’s chance of survival. Just like imprinting, this attachment process develops from the interaction between species-specific learning biases (such as infants’ strong tendency to look at faces) and the infant’s experience with his or her caregiver. Thus, the attachment process is viewed as having an innate basis, but the development and quality of infants’ attachments are highly dependent on the nature of their experiences with caregivers.

429

According to Bowlby, the initial development of attachment takes place in four phases.

Preattachment (birth to age 6 weeks). In this phase, the infant produces innate signals, most notably crying, that summon caregivers, and the infant is comforted by the ensuing interaction.

Preattachment (birth to age 6 weeks). In this phase, the infant produces innate signals, most notably crying, that summon caregivers, and the infant is comforted by the ensuing interaction.

Attachment-in-the-making (age 6 weeks to 6 to 8 months). During this phase, infants begin to respond preferentially to familiar people. Typically they smile, laugh, or babble more frequently in the presence of their primary caregiver and are more easily soothed by that person. Like Freud and Erik Erikson, Bowlby saw this phase as a time when infants form expectations about how their caregivers will respond to their needs and, accordingly, do or do not develop a sense of trust in them.

Attachment-in-the-making (age 6 weeks to 6 to 8 months). During this phase, infants begin to respond preferentially to familiar people. Typically they smile, laugh, or babble more frequently in the presence of their primary caregiver and are more easily soothed by that person. Like Freud and Erik Erikson, Bowlby saw this phase as a time when infants form expectations about how their caregivers will respond to their needs and, accordingly, do or do not develop a sense of trust in them.

Clear-cut attachment (between 6 to 8 months and 1½ years). In this phase, infants actively seek contact with their regular caregivers. They happily greet their mother when she appears and, correspondingly, may exhibit separation anxiety or distress when she departs (see Chapter 10, page 391). For the majority of children, the mother now serves as a secure base, facilitating the infant’s exploration and mastery of the environment.

Clear-cut attachment (between 6 to 8 months and 1½ years). In this phase, infants actively seek contact with their regular caregivers. They happily greet their mother when she appears and, correspondingly, may exhibit separation anxiety or distress when she departs (see Chapter 10, page 391). For the majority of children, the mother now serves as a secure base, facilitating the infant’s exploration and mastery of the environment.

Reciprocal relationships (from 1½ or 2 years on). During this final phase, toddlers’ rapidly increasing cognitive and language abilities enable them to understand their parents’ feelings, goals, and motives and to use this understanding to organize their efforts to be near their parents. As a result, a more mutually regulated relationship gradually emerges as the child takes an increasingly active role in developing a working partnership with his or her parents (Bowlby, 1969). Correspondingly, separation distress declines.

Reciprocal relationships (from 1½ or 2 years on). During this final phase, toddlers’ rapidly increasing cognitive and language abilities enable them to understand their parents’ feelings, goals, and motives and to use this understanding to organize their efforts to be near their parents. As a result, a more mutually regulated relationship gradually emerges as the child takes an increasingly active role in developing a working partnership with his or her parents (Bowlby, 1969). Correspondingly, separation distress declines.

internal working model of attachment the child’s mental representation of the self, of attachment figure(s), and of relationships in general that is constructed as a result of experiences with caregivers. The working model guides children’s interactions with caregivers and other people in infancy and at older ages.

The usual outcome of these phases is an enduring emotional tie uniting the infant and caregiver. In addition, the child develops an internal working model of attachment, a mental representation of the self, of attachment figures, and of relationships in general. This internal working model is based on the young child’s discovering the extent to which his or her caregiver could be depended on to satisfy the child’s needs and provide a sense of security. Bowlby believed that this internal working model guides the individual’s expectations about relationships throughout life. If caregivers are accessible and responsive, young children come to expect interpersonal relationships to be gratifying and they feel worthy of receiving care and love. As adults, they look for, and expect to find, satisfying and security-enhancing relationships similar to the ones they had with their attachment figures in childhood. If children’s attachment figures are unavailable or unresponsive, children develop negative perceptions of relationships with other people and of themselves (Bowlby, 1973, 1980; Bretherton & Munholland, 1999). Thus, children’s internal working models of attachment are believed to influence their overall adjustment, social behavior, perceptions of others, and the development of their self-esteem and sense of self (R. A. Thompson, 2006).

Ainsworth’s Research

Strange Situation a procedure developed by Mary Ainsworth to assess infants’ attachment to their primary caregiver

Mary Ainsworth, who began working with John Bowlby in 1950, provided empirical support for Bowlby’s theory, extending it in important ways and bringing the concept of the primary caregiver as a secure base to the fore. In research conducted in both Uganda (Ainsworth, 1967) and the United States, Ainsworth studied mother–infant interactions during infants’ explorations and separations from their mother. On the basis of her observations, she came to the conclusion that two key measures provide insight into the quality of the infant’s attachment to the caregiver: (1) the extent to which an infant is able to use his or her primary caregiver as a secure base, and (2) how the infant reacts to brief separations from, and reunions with, the caregiver (Ainsworth, 1973; Ainsworth et al., 1978).

430

Measurement of Attachment Security in Infancy

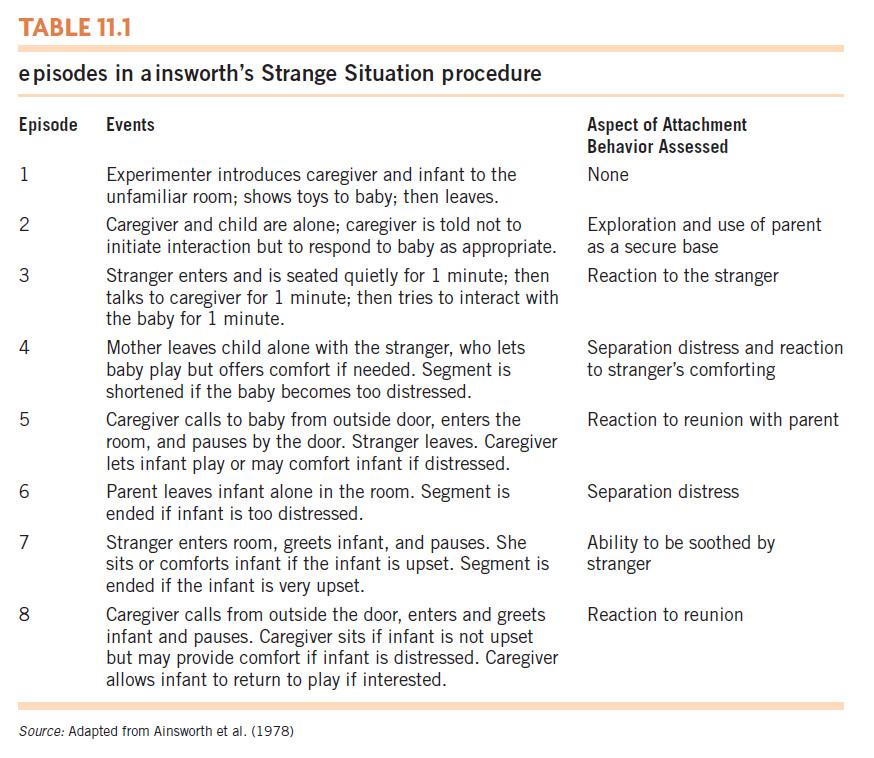

With these measures in mind, Ainsworth designed a laboratory test for assessing the security of an infant’s attachment to his or her parent. This test is called the Strange Situation because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the child and likely to heighten the child’s need for his or her parent. In this test, the infant, accompanied by the parent, is placed in a laboratory playroom equipped with interesting toys. After the experimenter introduces the parent and child to the room, the child is exposed to seven episodes, including two separations from, and reunions with, the parent, as well as two interactions with a stranger—one when the parent is out of the room and one when the parent is present (see Table 11.1). Each episode lasts approximately 3 minutes unless the child becomes overly upset. Throughout these episodes, observers rate infants’ behaviors, including their attempts to seek closeness and contact with the parent, their resistance to or avoidance of the parent, their interactions with the stranger, and their interactions with the parent from a distance using language or gestures.

431

secure attachment a pattern of attachment in which infants or young children have a high-quality, relatively unambivalent relationship with their attachment figure. In the Strange Situation, a securely attached infant, for example, may be upset when the caregiver leaves but may be happy to see the caregiver return, recovering quickly from any distress. When children are securely attached, they can use caregivers as a secure base for exploration.

Through her use of the Strange Situation, Ainsworth (1973) discerned three distinct patterns in infants’ behavior that seemed to indicate the quality or security of their attachment bond. These patterns—which are reflected in the infant’s behavior throughout the Strange Situation, but especially during the reunions with the parent—have been replicated many times in research with mothers, and sometimes with fathers. On the basis of these patterns, Ainsworth identified three attachment categories.

insecure attachment a pattern of attachment in which infants or young children have a less positive attachment to their caregiver than do securely attached children. Insecurely attached children can be classified as insecure/resistant (ambivalent), insecure/avoidant, or disorganized/disoriented.

The first attachment category—the one into which the majority of infants fall—is secure attachment. Babies in this category use their mother as a secure base during the initial part of the session, leaving her side to explore the many toys available in the room. As they play with the toys, these infants occasionally look back to check on their mother or bring a toy over to show her. They are usually, but by no means always, distressed to some degree when their mother leaves the room, especially when they are left totally alone. However, when their mother returns, they make it clear that they are glad to see her, either by simply greeting her with a happy smile or, if they have been upset during her absence, by going to her to be picked up and comforted. If they have been upset, their mother’s presence comforts and calms them, often enabling them to explore the room again. About 62% of typical middle-class children in the United States whose mother is not clinically disturbed fall into this category; for infants from lower socioeconomic groups, the rate is significantly lower—slightly less than 50% for children under 24 months of age (R. A. Thompson, 1998; van IJzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 1999).

insecure/resistant (or ambivalent) attachment a type of insecure attachment in which infants or young children are clingy and stay close to their caregiver rather than exploring their environment. In the Strange Situation, insecure/resistant infants tend to get very upset when the caregiver leaves them alone in the room. When their caregiver returns, they are not easily comforted and both seek comfort and resist efforts by the caregiver to comfort them.

The other two attachment categories that Ainsworth originally identified involve children who are rated as insecurely attached, that is, who have less positive attachment to their caregivers than do securely attached children. One type of insecurely attached infant is classified as insecure/resistant, or ambivalent. Infants in this category are often clingy from the beginning of the Strange Situation, staying close to the mother instead of exploring the toys. When their mother leaves the room, they tend to get very upset, often crying intensely. In the reunion, the insecure/resistant infant typically re-establishes contact with the mother, only to then rebuff her efforts at offering comfort. For example, the infant may rush to the mother bawling, with outstretched arms, signaling the wish to be picked up—but then, as soon as he or she is picked up, arch away from the mother or begin squirming to get free from her embrace. About 9% of typical middle-class children in the United States fall into the insecure/resistant category, but the percentage appears to be somewhat higher in many non-Western cultures (van IJzendoorn et al., 1999).

Video: Interview with Gilda Morelli

The other type of insecurely attached infant is classified as insecure/avoidant. Children in this category tend to avoid their mother in the Strange Situation. For example, they often fail to greet her during the reunions and ignore her or turn away while she is in the room. Approximately 15% of typical middle-class children fall into the insecure/avoidant category (van IJzendoorn et al., 1999).

insecure/avoidant attachment a type of insecure attachment in which infants or young children seem somewhat indifferent toward their caregiver and may even avoid the caregiver. In the Strange Situation, they seem indifferent toward their caregiver before the caregiver leaves the room and indifferent or avoidant when the caregiver returns. If the infant gets upset when left alone, he or she is as easily comforted by a stranger as by a parent.

Subsequent to Ainsworth’s original research, attachment investigators found that the reactions of a small percentage of children in the Strange Situation did not fit well into any of Ainsworth’s three categories. These children seem to have no consistent way of coping with the stress of the Strange Situation. Their behavior is often confused or even contradictory. For example, they may exhibit fearful smiles and look away while approaching their mother, or they may seem quite calm and contented and then suddenly display angry distress. They also frequently appear dazed or disoriented and may freeze in their behavior and remain still for a substantial period of time. These infants, labeled disorganized/disoriented, seem to have an unsolvable problem: they want to approach their mother, but they also seem to regard her as a source of fear from which they want to withdraw (Main & Solomon, 1990). About 15% of middle-class American infants fall into this category. However, this percentage may be considerably higher among maltreated infants (van IJzendoorn et al., 1999), among infants whose parents are having serious difficulties with their own working models of attachment (van IJzendoorn, 1995) (see Box 11.1), and among preschoolers from lower socioeconomic backgrounds (Moss, Cyr, & Dubois-Comtois, 2004; van IJzendoorn et al., 1999).

disorganized/disoriented attachment a type of insecure attachment in which infants or young children have no consistent way of coping with the stress of the Strange Situation. Their behavior is often confused or even contradictory, and they often appear dazed or disoriented.

432

A key question, of course, is whether there is some similarity between infants’ behavior in the Strange Situation and their behavior at home. The answer is yes (J. Solomon & George, 1999). For example, compared with infants who are insecurely attached, 12-month-olds who are securely attached exhibit more enjoyment of physical contact, are less fussy or difficult, and are better able to use their mothers as a secure base for exploration at home (Pederson & Moran, 1996). Thus, they are more likely to learn about their environments and to enjoy doing so. In addition, children’s behavior in the Strange Situation correlates with attachment scores derived from observing children’s interactions with their mother over several hours (van IJzendoorn et al., 2004). As you will shortly see, attachment measurements derived from the Strange Situation also correlate with later behavior patterns.

Box 11.1: individual differences: Parental Attachment Status

adult attachment models working models of attachment in adulthood that are believed to be based on adults’ perceptions of their own childhood experiences—especially their relationships with their parents—and of the influence of these experiences on them as adults

According to attachment theorists, parents have “working models” of attachment relationships that guide their interactions with their children and thereby influence the security of their children’s attachment. These adult attachment models are based on adults’ perceptions of their own childhood relationships with their parents and on the continuing influence of those relationships (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985).

Parental models of attachment often are measured with the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), developed by Mary Main, Carol George, and their colleagues. In this interview, adults are asked to discuss their early childhood attachments and to evaluate them from their current perspectives (Hesse, 1999). For example, they are asked to describe their childhood relationship with each parent, including what their parent did for them when they were hurt or upset; what they remember about separations from the parent; if they ever felt rejected by the parent; and how their adult personalities were shaped by these experiences. These descriptions are used to classify the adults into four major attachment groups—autonomous (or secure), dismissing, preoccupied, and unresolved/disorganized.

Adults who are rated autonomous, or secure, are those whose descriptions are coherent, consistent, and relevant to the questions. Generally, autonomous adults describe their past in a balanced manner, recalling both positive and negative features of their parents and of their relationships with them. They also report that their early attachments were influential in their development. Autonomous adults discuss their past in a consistent and coherent manner even if they did not have supportive parents.

Adults in the other three categories are considered to be insecure in their attachment status. Dismissing adults often insist that they cannot remember attachment-related interactions with their parents, or they minimize the impact that these experiences had on them. They may also contradict themselves when describing their attachment-related experiences and seem unaware of their inconsistencies. For example, they may describe their mother in glowing terms and later talk about how she got angry at them whenever they hurt themselves (Hesse, 1999).

Preoccupied adults are intensely focused on their parents and tend to give confused and angry accounts of attachment-related experiences. A prototypical response is “I got so angry [at my mother] that I picked up the soup bowl and threw it at her” (Hesse, 1999, p. 403). Preoccupied adults often seem to be so caught up in their attachment memories that they cannot provide a coherent description of them. Unresolved/disorganized adults appear to be suffering the aftermath of past traumatic experiences of loss or abuse. Their descriptions of their childhood show striking lapses in reasoning and may not make sense. For example, an unresolved/disorganized adult may indicate that he or she believes that a dead parent is still alive or that the parent died because of negative thoughts that the adult had about the parent (Hesse, 1999). In North American samples of White mothers who have no diagnosed psychological disturbance, approximately 58% are classified as secure, 23% as dismissing, and 19% as preoccupied. This distribution is generally similar in samples in other countries such as India, China, and in countries in Africa and South America (van IJzendoorn & Bakermans-Kranenburg, 2010).

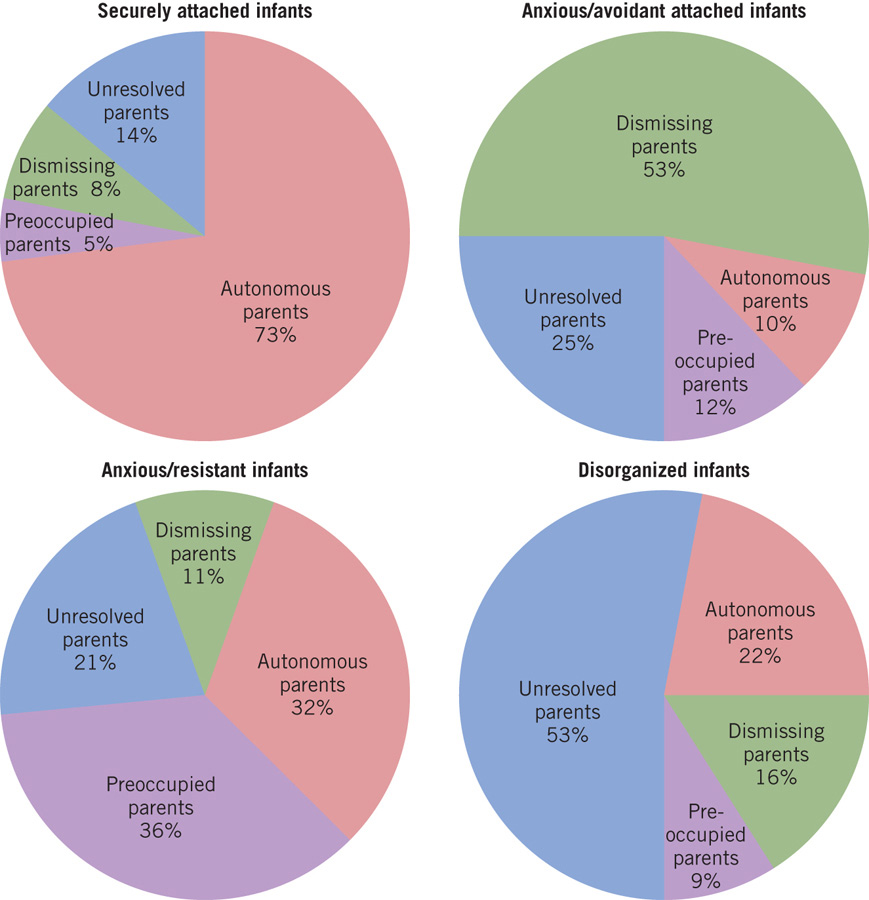

Parents’ attachment classification predicts both their sensitivity toward their own children and their children’s attachment to them. Autonomous parents tend to be sensitive, warm parents, and their infants usually are securely attached to them (Magai et al., 2000; Steele, Steele, & Fonagy, 1996; van IJzendoorn, 1995). Correspondingly, parents in the other three categories tend to have insecurely attached infants, although the relation is not very strong for preoccupied parents (see figure). Unresolved parents are particularly likely to have disorganized infants (Hesse & Main, 2006; Madigan et al., 2007), probably due, in part, to their low sensitivity as parents, including either a negative and controlling, or a disengaged and inattentive, style of parenting (H. N. Bailey et al., 2007; Busch, Cowan, & Cowan, 2008; Whipple, Bernier, & Mageau, 2011). This general pattern of findings has emerged in studies in a number of different Western cultures (Hesse, 1999).

The reason for the association between parents’ attachment models and the security of their children’s attachments is not clear. Autonomous parents appear to be more sensitively attuned to their children, which likely contributes to their children’s being securely attached (Mills-Koonce et al., 2011; Pederson et al., 1998; Verschueren et al., 2006). For example, securely attached parents are less angry and intrusive in their interactions with their children than are preoccupied parents (Adam, Gunnar, & Tanaka, 2004). And it may very well be that autonomous adults, who tend to have been securely attached as infants or children (E. Waters, et al., 2000), are more sensitive and skilled parents because of their own early experience with sensitive parenting (Benoit & Parker, 1994), although the evidence for this is somewhat inconsistent (H. N. Bailey et al., 2007).

433

However, it is not clear what adults’ responses on the AAI actually represent. Although attachment theorists claim that the content and coherence of adults’ discussions of their own early childhood experiences reflect the effects of these early experiences, there is little evidence to prove (or disprove) this theory (Fox, 1995; R. A. Thompson, 1998). Rather than reflecting their own childhood experiences, adults’ discussions of them may instead reflect their personal theories about development and child rearing, their current level of psychological functioning, or their personality—all of which also may affect their parenting. Regardless of the reason, the relation between parents’ attachment models and their infants’ attachment suggests that parents’ beliefs about parenting and about relationships have a powerful influence on the bond between them and their children (R. A. Thompson, 1998).

434

Cultural Variations in Attachment

Because human infants are believed to be biologically predisposed to form attachments with their caregivers, one might expect attachment behaviors to be similar in different cultures. In fact, in large measure, infants’ behaviors in the Strange Situation are similar across numerous cultures, including those of China, western Europe, and various parts of Africa. In all these cultures, there are securely attached, insecure/resistant, and insecure/avoidant infants, with the average percentages for these groupings being approximately 53%, 18%, and 21%, respectively (van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999; van IJzendoorn et al., 1999). Although relatively few studies in non-Western cultures have included the category “disorganized/disoriented,” the findings of those that have suggest that the percentage of babies who fall into this category is roughly 21%, which is not statistically different from the rates in Western countries (Behrens, Hesse, & Main, 2007; van IJzendoorn et al., 1999).

Despite these general consistencies in attachment ratings, some interesting and important differences in children’s behavior in the Strange Situation have been noted in certain other cultures (van IJzendoorn & Sagi-Schwartz, 2008; Zevalkink, Riksen-Walraven, & Van Lieshout, 1999). For example, while Japanese infants in one study showed roughly the same percentage of secure attachment in the Strange Situation as middle-class U.S. infants do (about 62% to 68%), in some research, there was a notable difference in the types of insecure attachment they displayed. All the insecurely attached Japanese infants were classified as insecure/resistant, which is to say that none exhibited insecure/avoidant behavior (Takahashi, 1986). Similarly, in a sample of Korean families, insecure/avoidant children were very rare (Jin et al., 2012).

One possible explanation for this is that Japanese culture exalts the idea of oneness between mother and child; correspondingly, its child-rearing practices, compared with those in the United States, foster greater mother–infant closeness and physical intimacy, as well as infants’ greater dependency on their mother (Rothbaum et al., 2000). Thus, in the Strange Situation, Japanese children may desire more bodily contact and reassurance than do U.S. children and therefore may be more likely to exhibit anger and resistance to their mother after being deprived of contact with her (Mizuta et al., 1996).

Another explanation is that the Strange Situation might not always have been a valid measure because it is possible that some Japanese parents were self-conscious and inhibited in the Strange Situation setting, which, in turn, could have affected their children’s behavior. It is also possible that how young children react in the Strange Situation is affected by their prior experience with unfamiliar situations and people. Thus, part of the difference in the rates of insecure/resistant attachment shown by Japanese and U.S. infants may be due to the fact that, at the time that many of the studies in question were conducted (the 1980s), very few infants in Japan were enrolled in day care and thus did not experience frequent separations from their mother. Consistent with this argument, a more recent study, which looked at the reunion behaviors of 6-year-old Japanese children who had all attended preschool, did not find a high number of insecure/resistant attachments (Behrens, Hesse, & Main, 2007). It is therefore possible that differences in children’s experiences with separation within or across cultures contribute substantially to the variability in children’s behavior in the Strange Situation.

435

Factors Associated with the Security of Children’s Attachment

One obvious question that arises in trying to explain differences in attachment patterns is whether the parents of securely attached and insecurely attached children differ in the way they interact with their children. Evidence suggests that they do.

Parental Sensitivity

parental sensitivity an important factor contributing to the security of an infant’s attachment. Parental sensitivity can be exhibited in a variety of ways, including responsive caregiving when an infant is distressed or upset and engaging in coordinated play with the infant.

Attachment theorists have argued that the most crucial parental factor contributing to the development of a secure attachment is parental sensitivity (Ainsworth et al., 1978). One key aspect of parental sensitivity is consistently responsive caregiving. The mothers of securely attached 1-year-olds tend to read their babies’ signals accurately, responding quickly to the needs of a crying baby and smiling back at a beaming one. Positive exchanges between mother and child, such as mutual smiling and laughing, making sounds at each other, or engaging in coordinated play, are a characteristic of sensitive parenting that may be particularly important in promoting secure attachment (De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997; Nievar & Becker, 2008).

In contrast, the mothers of insecure/resistant infants tend to be inconsistent in their early caregiving: they sometimes respond promptly to their infants’ distress, but sometimes they do not. These mothers often seem highly anxious and overwhelmed by the demands of caregiving. Mothers of insecure/avoidant infants tend to be indifferent and emotionally unavailable, sometimes rejecting their baby’s attempts at physical closeness (Isabella, 1993; Leerkes, Parade, & Gudmundson, 2011).

Mothers of disorganized/distressed infants sometimes exhibit abusive, frightening, or disoriented behavior and may be dealing with unresolved loss or trauma (L. M. Forbes et al., 2007; Madigan, Moran, & Pederson, 2006; van IJzendoorn et al., 1999). In response, their infants often appear to be confused or frightened (E. A. Carlson, 1998; Hesse & Main, 2006). By age 3 to 6, perhaps in an attempt to manage their emotions, these children often try to control their mother’s activities and conversation, either in an excessively helpful and emotionally positive way, basically trying to cheer her up, or in a hostile or aggressive way (Moss et al., 2004; J. Solomon, George, & De Jong, 1995).

The association between maternal sensitivity and the quality of infants’ and children’s attachment has been demonstrated in numerous studies involving a variety of cultural groups (Beijersbergen et al., 2012; Mesman et al., 2012; Posada et al., 2004; Valenzuela, 1997; van IJzendoorn et al., 2004). Particularly striking is the finding that infants whose mothers are insensitive show only a 38% rate of secure attachment, which is much lower than the typical rate (van IJzendoorn & Sagi, 1999). An association between fathers’ sensitivity and the security of their children’s attachment has also been found, though it is somewhat weaker than that for mothers (G. L. Brown, Mangelsdorf, & Neff, 2012; Lucassen et al., 2011; van IJzendoorn & De Wolff, 1997).

Given that all the research discussed above involves correlations between parental sensitivity and children’s attachment status, it is impossible to determine whether parents’ sensitivity was actually responsible for their children’s security of attachment or was merely associated with it. It could be that some other factor, such as the presence or absence of marital conflict, affected both the parents’ sensitivity and the child’s security of attachment. However, evidence that parental sensitivity does in fact have a causal effect on infants’ attachment has been provided by short-term experimental interventions designed to enhance the sensitivity of mothers’ caregiving. These interventions, discussed in Box 11.2, have been found to increase not only mothers’ sensitivity with their infants but also the security of their infants’ attachment (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, 2003; van IJzendoorn, Juffer, & Duyvesteyn, 1995). Moreover, in twin studies of infants’ attachment, nearly all the variation in attachments was due to environmental factors (Bokhorst et al., 2003; Roisman & Fraley, 2008).

436

Nonetheless, recent research findings indicate that some individual differences in attachment behaviors may be linked in complex ways to specific genes (S. C. Johnson & Chen, 2011). One study, for instance, focused on the possible influence that allelic variants of the serotonin transporter gene, SLC6A4 (formerly named 5HTT), might have on behavior in the Strange Situation. The participants were Ukrainian preschoolers, some of whom had been raised in institutions and some of whom had been raised in their biological family. The researchers found that children with a SLC6A4 variant frequently associated with reactivity and vulnerability in the face of stress exhibited less attachment security and more attachment disorganization if they grew up in an institution than did preschoolers with the same variant who lived with their family. In contrast, preschoolers who were raised in an institution but had a different SLC6A4 genotype, one that is frequently associated with less reactivity and less vulnerability, did not exhibit adverse attachment behavior (Bakermans-Kranenburg, Dobrova-Krol, & van IJzendoorn, 2012).

Box 11.2: applications: Interventions and Attachment

To determine whether parental sensitivity is causally related to differences in security of attachment, researchers have designed special intervention studies. In these studies, parents in an experimental group are first trained to be more sensitive in their caregiving. Later, the attachment statuses of their infants are compared with those of children whose parents, as members of a control group, experienced no intervention (van IJzendoorn et al., 1995).

An intervention study of this sort was conducted in the Netherlands by Daphna van den Boom (1994, 1995). Infants who were rated as irritable shortly after their birth were selected for the study because some investigators (but not all) have found that irritable infants may be at risk for insecure attachment. When the infants were about 6 months of age, half of their mothers were randomly chosen to be in the experimental group for three months. These mothers were taught to be attuned to their infants’ cues regarding their wants and needs and to respond to them in a manner that fostered positive exchanges between mother and child. The remaining mothers in the control group received no special training.

At the end of the intervention, mothers in the experimental group were more attentive, responsive, and stimulating to their infants than were those in the control group. In turn, their infants were more sociable, explored the environment more, were better able to soothe themselves, and cried less than infants whose mothers did not receive the intervention. Especially significant, the rates of secure attachment were notably higher for infants whose mothers were in the experimental group—62% compared with 22%.

In a longitudinal follow-up at 18 months of age, 72% of the children in the intervention group were securely attached, compared with 26% of the children in the control group. When their infants were 24 months old, mothers in the intervention group were, as earlier, more accepting, accessible, cooperative, and sensitive with their infants than were the control-group mothers, and their children were more cooperative. Similar findings were obtained when the children were 3½ years old.

Experimental interventions have also been used to improve depressed mothers’ attachments to their children. The assumption underlying these interventions is that depressed mothers, whose relationship with their children is often impaired, can be taught skills and information that improve the quality of the mother–infant relationship. In one study, for example, investigators taught depressed mothers parenting skills and provided them with information about child development to enhance their coping and social-support skills (Toth et al., 2006). In another study (van Doesum et al., 2008), depressed mothers were videotaped bathing or feeding their infant and then, after viewing the film, were trained to respond to the infant with more sensitive and appropriate communicative behaviors. In addition, this intervention included such techniques as having a home visitor model positive caregiving, encouraging the mother to change her negative patterns of thinking about her infant and about her own parenting skills, and providing practical information on child development. Both studies were successful in improving the quality of the mother–infant attachment relationship.

Other interventions that used similar techniques have also succeeded in reducing the rate of disorganized attachment, and increasing the rate of secure attachment, for children who were at risk for maternal maltreatment (Bernard et al., 2012; Moss et al., 2011). From the evidence of experimental studies such as these, it seems clear that sensitive parenting contributes to infants’ and young children’s security of attachment.

437

There is also some research indicating that a gene involved in the dopamine system, called DRD4, is associated with disorganized attachment when an infant is in a stressful environment (as when the mother is suffering from trauma or loss) but is associated with greater attachment security in a less stressful context (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2007). This research, along with the study discussed above and other recent work, highlights the concept of differential susceptibility discussed in Chapter 10. That is, it suggests that certain genes result in children’s being differentially susceptible to the quality of their rearing environment, such that those with the “reactive” genes benefit more from having a secure attachment (e.g., are better adjusted and more prosocial than their peers) but do more poorly if they have an insecure attachment (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2007, 2011; Kochanska, Philibert, & Barry, 2009). Although this theory needs more validation, it appears that infants’ genetic makeup affects the degree to which their rearing environment alters their adjustment and social functioning.

Does Security of Attachment Have Long-Term Effects?

The reason that developmentalists are so interested in children’s attachment status is that securely attached infants appear to grow up to be better adjusted and more socially skilled than do insecurely attached children. One explanation for this may be that children with a secure attachment are more likely to develop positive and constructive internal working models of attachment. (Recall that children’s working models of attachment are believed to shape their adjustment and social behavior, their self-perceptions and sense of self, and their expectations about other people, and there is some direct evidence for this belief [e.g., S. C. Johnson & Chen, 2011; S. C. Johnson, Dweck, & Chen, 2007].) In addition, children who experience the sensitive, supportive parenting that is associated with secure attachment are likely to learn that it is acceptable to express emotions in an appropriate way and that emotional communication with others is important (Cassidy, 1994; Riva Crugnola et al., 2011; Kerns et al., 2007). In contrast, insecure/avoidant children, whose parents tend to be nonresponsive to their signals of need and distress, are likely to learn to inhibit emotional expressiveness and to not seek comfort from other people (Bridges & Grolnick, 1995).

Consistent with these patterns, children who were securely attached in infancy or early childhood later seem to have closer, more harmonious relationships with peers than do children who were insecurely attached (McElwain, Booth-LaForce, & Wu, 2011). For example, they are somewhat more regulated, sociable, and socially competent with peers (Lucas-Thompson & Clarke-Stewart, 2007; Panfile & Laible, 2012; Vondra et al., 2001). Correspondingly, they are less anxious, depressed, or socially withdrawn (Brumariu & Kerns, 2010)—especially compared with children who had insecure/resistant attachments (Groh et al., 2012)—as well as less aggressive and delinquent (Fearon et al., 2010; Groh et al., 2012; Hoeve et al., 2012; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2006). They are also better able to understand others’ emotions (Steele, Steele, & Croft, 2008; R. A. Thompson, 2008) and display more helping, sharing, and concern for peers (N. Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2006; Kestenbaum, Farber, & Sroufe, 1989; Panfile & Laible, 2012). Securely attached children are also more likely to report positive emotion and to exhibit normal rather than abnormal patterns of reactivity to stress (Bernard & Dozier, 2010; Borelli et al., 2010; Luijk et al., 2010). Finally, secure attachment in infancy even predicts positive peer and romantic relationships and emotional health in adolescence (E. A. Carlson, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2004; Collins et al., 1997) and early adulthood (Englund et al., 2011).

438

Although there are only a few studies in which infants’ attachments to both parents were assessed, it appears that children may be most at risk if they have insecure attachments to both their mother and their father. In a study in which attachment was assessed at 15 months of age, children with insecure attachments to both parents were especially prone to problem behaviors such as aggression and defiance in elementary school. Having either one secure attachment or secure attachments with both parents was associated with low levels of problem behaviors (Kochanska & Kim, 2013). However, it is not clear yet if having one secure attachment buffers against other types of negative outcomes, such as internalizing problems (e.g., anxiety, depression) or problems in interpersonal relations.

Clearly, then, children’s security of attachment is related to their later psychological, social, and cognitive functioning. However, experts disagree on the meaning of this relationship. As noted, some theorists believe that early security of attachment has important effects on later development because it provides enduring working models of positive relationships (Bowlby, 1973; Fraley, 2002; Sroufe, Egeland, & Kreutzer, 1990). This view implies that the effects of early attachment remain stable over time. Other theorists believe that early security of attachment predicts later development primarily to the degree that the child’s environment—including the quality of parent–child interactions—does not change (M. E. Lamb et al., 1985). In other words, early security of attachment predicts children’s functioning at an older age because “good” parents tend to remain good parents and “bad” parents tend to remain bad parents.

Empirical findings support both perspectives to some degree. One study reported that even if children functioned poorly during the preschool years, those who had a secure attachment and adapted well during infancy and toddlerhood were more socially and emotionally competent in middle childhood than were their peers who had been insecurely attached (Sroufe et al., 1990). This suggests that a child’s early attachment has some effects over time. However, although there is often considerable stability in attachment security (Fraley, 2002; C. E. Hamilton, 2000), there is also evidence that children’s security of attachment can change somewhat as their environment changes—for example, with the onset or termination of stress and conflict in the home (Frosch, Mangelsdorf, & McHale, 2000; M. Lewis, Feiring, & Rosenthal, 2000; Moss et al., 2004) or a pronounced shift in the mother’s typical behavior with the child (L. M. Forbes et al., 2007) or in her sensitivity (Beijersbergen et al., 2012). In such cases, current parent–child interactions or parenting behaviors predict the child’s social and emotional competence at that age better than measures of attachment taken at younger ages (R. A. Thompson, 1998; Youngblade & Belsky, 1992). Indeed, children’s development can be predicted better from the combination of both their early attachment status and the quality of subsequent parenting (e.g., maternal sensitivity at an older age) than from either factor alone (Belsky & Fearon, 2002). Finally, it must be emphasized again that most of the research on attachment is correlational, so it is difficult to pin down causal relations.

439

review:

Evidence revealing the poor development of infants who are deprived of consistent, caring relationships with an adult led to the systematic study of infants’ early attachments. John Bowlby proposed that a secure attachment provides children with a secure base for exploration and contributes to a positive internal working model of relationships in general. According to attachment research, pioneered by Mary Ainsworth, children’s attachment relationships with caregivers can be classified as secure, insecure/avoidant, insecure/resistant, and disorganized/disoriented. Children in these categories display similarities across cultures, although the percentage of children in different attachment groups sometimes varies across cultures or subcultures.

Factors that appear to influence the security of attachment include parents’ sensitivity and responsiveness to their children’s needs and the parents’ own attachment status. Children’s security of attachment to their caregivers predicts the quality of their relationships with family members, which is likely to affect how children feel about and evaluate themselves. These relations may hold not only because the sensitivity of parenting in the early years of life has long-term effects but also because sensitive parents usually continue to provide effective parenting, whereas less sensitive parents continue to interact with the children in ways that undermine children’s optimal development.