Conceptions of the Self

As we have noted, children’s security of attachment to caregivers affects their feelings about themselves, especially in regard to their relationships with other people. Thus, it is not surprising that children’s attachment experiences early in life likely color their early sense of self, which emerges in infancy and carries over into childhood (R. A. Thompson, 2008). However, the development of a sense of self is an ongoing, very complex process that involves much more than early-childhood attachments and notions of the self.

self a conceptual system made up of one’s thoughts and attitudes about oneself

When we speak of the self, we are referring to a conceptual system made up of one’s thoughts and attitudes about oneself. This conceptual system can include thoughts about one’s own physical being (e.g., body, possessions), social characteristics (e.g., relationships, personality, social roles), and “spiritual” or internal characteristics (e.g., thoughts and psychological functioning). It also may include notions about how the self changes or remains the same over time, beliefs about one’s own role in shaping these processes, and even reflections on one’s own consciousness of selfhood (Damon & Hart, 1988). The development of the self is important because individuals’ self-conceptions, including the ways they view and feel about themselves, appear to influence their overall feelings of well-being and competence.

440

The Development of Conceptions of Self

Children’s sense of self changes in fairly dramatic ways across infancy, childhood, and adolescence. It continues to develop into adulthood, becoming more complex as the individual’s emotional and cognitive development deepens.

The Self in Infancy

There is compelling evidence that infants have a rudimentary sense of self in the first months of life. As noted in Chapter 5 and Chapter 10, by 2 to 4 months of age, infants have a sense of their ability to control objects outside themselves, as is clear both from their enthusiasm when they can make a mobile move by pulling a string attached to their arm and from their anger when their efforts no longer have an effect. They also seem to have some understanding of their own bodily movements. For instance, when viewing live video images of their own leg movements, 3- to 5-month-old infants looked longer and moved their legs more when the video showed their leg movements from a perspective other than their own (e.g., when the right and left legs in the video image appeared to move in opposition to the leg movements the infants were performing) than when the video image showed leg movements as the infants themselves saw them (Rochat & Morgan, 1995). Perhaps their longer looking reflected their surprise at, or interest in, seeing the reversal of their leg movements (Rochat & Striano, 2002).

A sense of self becomes much more distinct at about 8 months of age, when infants react with separation distress if parted from their mother, suggesting that they recognize that they and their mother are separate entities. Further indications that children view others as beings different from themselves are apparent by age 1. As discussed in Chapter 4, around their 1st birthday, infants begin to show joint attention with respect to objects in the environment. For example, they will visually follow a caregiver’s pointing finger to find the object that the caregiver is calling attention to, and then turn back to the caregiver to confirm that they are indeed looking at the intended object (Stern, 1985). They sometimes will also give objects to an adult in an apparent effort to engage the adult in their activities (M. J. West & Rheingold, 1978).

Infants’ emerging recognition of the self becomes more directly apparent by 18 to 20 months of age, when many children can look into a mirror and realize that they are looking at themselves (Asendorpf, Warkentin, & Baudonnière, 1996; M. Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979; Nielsen, Suddendorf, & Slaughter, 2006). In studies that test this ability, an experimenter surreptitiously puts a dot of rouge on a child’s face, places the child in front of a mirror, and then asks the child who the person with the red spot is, or tells the child to clean the spot off the person in the mirror. Children younger than 18 months old often respond by trying to touch the image in the mirror, or they do nothing. By about the age of 18 months, however, many children touch the rouge on their own face, so it is assumed that they realize that the mirror image is a self-reflection.

441

By age 2, many children can recognize themselves in photographs. In one study, 63% of a group of 20- to 25-month-olds picked themselves out when presented with pictures of themselves and two same-sex, same-age children. By approximately age 30 months, 97% of the children immediately picked their own photograph (Bullock & Lütkenhaus, 1990).

During their third year, children’s self-awareness becomes quite clear in other ways as well. As you saw in Chapter 10, 2-year-olds exhibit embarrassment and shame—emotions that obviously require a sense of self (M. Lewis, 1995, 1998). The strength of 2-year-olds’ awareness of self is even more evident in their notorious self-assertion, which has led to the period between ages 2 and 3 being called the “terrible twos.” During this time, children often try to determine their activities and goals independent of, and often in direct opposition to, what their parents (and other adults) want them to do (Bullock & Lütkenhaus, 1990).

Two-year-olds’ self-awareness is also evident in, and is enhanced by, their use of language. They can, for example, use pronouns to refer to themselves (“me,” “mine”) and can label themselves by name (e.g., “Daddy take Julia’s book”) (E. Bates, 1990). Young children can also use language to store in memory their own experiences and behavior, giving them access to information about themselves and their past. Thus, language makes it possible for children to construct a narrative of their own “life story” and develop a more enduring picture of the self (Harter, 2012; R. A. Thompson, 2006).

Parents contribute to the child’s expanding self-image by providing descriptive information about the child (“You’re such a big boy”), evaluative descriptions of the child (“You’re so smart”), and information about the degree to which the child has met rules and standards (“Good girls don’t hit their baby sisters”). As noted in Chapter 4, parents also collaborate in children’s construction of autobiographical memory by reminding them of their past experiences (Snow, 1990).

The Self in Childhood

As children progress through childhood, their conception of themselves becomes increasingly complex and encompassing. This developmental pattern in self-understanding has been vividly illustrated by Susan Harter, a leading researcher on children’s emerging sense of self. Combining statements made by a wide array of children in a number of empirical studies, Harter has constructed composite examples of children’s typical self-descriptive statements at different ages. The following is a composite example of how 3- to 4-year-olds describe themselves:

I’m three years old and I live in a big house with my mother and father and my brother, Jason, and my sister, Lisa. I have blue eyes and a kitty that is orange and a television in my room. I know all of my ABC’s, listen: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, L, K, O, M, P, Q, X, Z. I can run real fast. I like pizza, and I have a nice teacher at preschool. I can count up to 10, want to hear me? I love my dog Skipper. I can climb to the top of the jungle gym—I’m not scared! I’m never scared! I’m always happy…. I’m really strong. I can lift this chair, watch me!

(Harter, 1999, p. 37)

As this composite self-description demonstrates, at age 3 to 4, children understand themselves in terms of concrete, observable characteristics related to physical attributes (“I have blue eyes”), physical activities and abilities (“I can run real fast”), social relationships (“my brother, Jason, and my sister, Lisa”), and psychological traits (“I’m always happy”) (Damon & Hart, 1988; Harter, 1999). Their focus on observable features is further reflected by the fact that the prototypical 3-year-old in the example bragged about particular skills such as running fast and did not make generalizations about his/her overall ability as an athlete. Even when the child made a general statement about himself/herself (“I’m really strong”), this statement was closely tied to actual behavior (lifting a chair). Young children also describe themselves in terms of their preferences (“I love my dog Skipper”) and possessions (“I have…a kitty…and a television”).

442

The composite example reflects another characteristic typical of children’s self-concept during the preschool years: their self-evaluations are unrealistically positive (Trzesniewski, Kinal, & Donnellan, 2010). Young children seem to think that they are really like what they want to be (Harter & Pike, 1984; Stipek, Roberts, & Sanborn, 1984). For example, the child in the composite self-description claimed mastery of the ABCs but clearly lacked it. Maintaining positive illusions about themselves is relatively easy for young children because they usually do not consider their own prior successes and failures when assessing their abilities. Even if they have failed badly at a task several times, they are likely to believe that they will succeed on the next try (Ruble et al., 1992).

social comparison the process of comparing aspects of one’s own psychological, behavioral, or physical functioning to that of others in order to evaluate oneself

Children begin to refine their conceptions of self in elementary school, in part because they increasingly engage in social comparison, comparing themselves with others in terms of their characteristics, behaviors, and possessions (“He is bigger than me”). At the same time, they increasingly pay attention to discrepancies between their own and others’ performance on tasks (“She got an A on the test and I only got a C”) (Chayer & Bouffard, 2010; Frey & Ruble, 1985). By middle to late elementary school, children’s conceptions of self have begun to become integrated and more broadly encompassing, as is illustrated by the following composite self-description that would be typical of a child between the ages of 8 and 11:

I’m pretty popular, at least with the girls. That’s because I’m nice to people and helpful and can keep secrets. Mostly I am nice to my friends, although if I get in a bad mood I sometimes say something that can be a little mean.…At school, I’m feeling pretty smart in certain subjects like Language Arts and Social Studies.…But I’m feeling pretty dumb in Math and Science, especially when I see how well a lot of the other kids are doing. Even though I’m not doing well in those subjects, I still like myself as a person, because Math and Science just aren’t that important to me. How I look and how popular I am are more important. I also like myself because I know my parents like me and so do other kids. That helps you like yourself.

(Harter, 1999, p. 48)

The developmental changes in older children’s conceptions of self reflect cognitive advances in their ability to use higher-order concepts that integrate more specific behavioral features of the self. For example, the child in the preceding self-description was able to relate being “popular” to several behaviors, such as being “nice to others” and being able to “keep secrets.” In addition, older children can coordinate opposing self-representations (“smart” and “dumb”) that, at a younger age, they would have considered mutually exclusive (Harter, 1999, 2012; Marsh, Craven, & Debus, 1998). The newfound cognitive capacity to form higher-order conceptions of the self allows older children to construct more global views of themselves and to evaluate themselves as a person overall. These abilities result in a more balanced and realistic assessment of the self, although they also can result in feelings of inferiority and helplessness (see the discussion of achievement motivation in Chapter 9).

443

The preceding self-description also reflects the fact that schoolchildren’s self-concepts are increasingly based on others’ evaluations of them, especially those of their peers. Consequently, their self-descriptions often contain a pronounced social element and focus on characteristics that may influence their place in their social networks, as reflected in the following interview:

WHAT ARE YOU LIKE? I am friendly.

WHY IS THAT IMPORTANT? Other kids won’t like you if you aren’t.

(Damon & Hart, 1988, p. 60)

Because older school-aged children’s conceptions of self are strongly influenced by the opinions of others, children at this age are vulnerable to low self-esteem if others view them negatively or as less competent than their peers (Harter, 2006).

The Self in Adolescence

Children’s conceptions of self change in fundamental ways across adolescence, due in part to the emergence of abstract thinking during this stage of life (see Chapter 4). The ability to use this kind of thinking allows adolescents to conceive of themselves in terms of abstract characteristics that encompass a variety of concrete traits and behaviors. Consider the following composite self-description of a young adolescent, 11 to 13 years old:

I’m an extrovert with my friends: I’m talkative, pretty rowdy, and funny.…All in all, around people I know pretty well I’m awesome, at least I think my friends think I am. I’m usually cheerful when I’m with my friends, happy and excited to be doing things with them.…With my parents…I feel sad as well as mad and also hopeless about ever pleasing them.…At school, I’m pretty intelligent. I know that because I’m smart when it comes to how I do in classes, I’m curious about learning new things, and I’m also creative when it comes to solving problems. My teacher says so.…I can be a real introvert around people I don’t know well—I’m shy, uncomfortable, and nervous. Sometimes I’m simply an airhead, I act really dumb and say things that are just plain stupid….

(Harter, 1999, p. 60)

As is evident in this composite example, young people’s concern over their social competence and their social acceptance, especially by peers, intensifies in early adolescence (Damon & Hart, 1988). The example also illustrates young adolescents’ ability to arrive at higher-level, abstract self-descriptions such as “extrovert” based on personal traits such as “talkative,” “rowdy,” and “funny.”

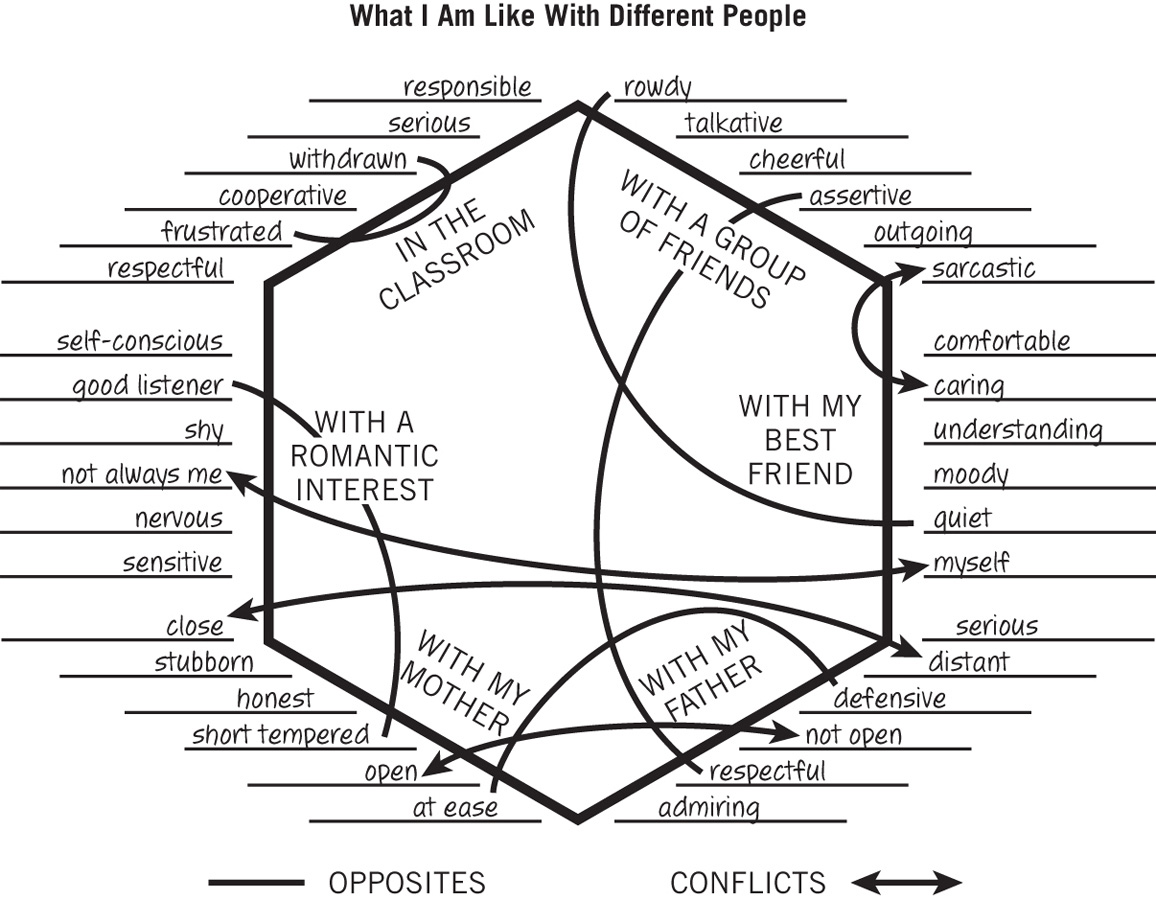

Particularly notable is the fact that adolescents can conceive of themselves in terms of a variety of selves, depending on the context. The adolescent in the composite, for instance, describes himself/herself as a somewhat different person with friends and with parents, as well as with familiar and unfamiliar people. In part, this may be because young adolescents tend to think about each of their abstract representations of the self separately from other abstractions and cannot integrate them (Higgins, 1991). Consequently, in terms of their overall sense of themselves, it does not overly concern young adolescents that the person they appear to be can vary according to the context (see Figure 11.1).

personal fable a form of adolescent egocentrism that involves beliefs in the uniqueness of one’s own feelings and thoughts

According to David Elkind (1967), thinking about the self in early adolescence is characterized by a form of egocentrism called the personal fable, in which adolescents overly differentiate their feelings from those of others and come to regard themselves, and especially their feelings, as unique and special. They may believe that only they can experience whatever misery or rapture or confusion they are currently feeling. This belief is typified in the adolescent assertions “But you don’t know how it feels” and “My parents don’t understand me, what do they know about what it’s like to be a teenager?” (Elkind, 1967; Harter, 1999, p. 76). The tendency to exhibit this type of egocentrism is often still evident in late adolescence and may even increase in boys (P. D. Schwartz, Maynard, & Uzelac, 2008).

444

imaginary audience the belief, stemming from adolescent egocentrism, that everyone else is focused on the adolescent’s appearance and behavior

The kind of egocentrism that underlies adolescents’ personal fables also causes many adolescents to be preoccupied with what others think of them (Elkind, 1967; Harter, 1999; Rosenberg, 1979). This preoccupation is exhibited in what Elkind (1967) has labeled as the adolescent’s belief in an imaginary audience. According to Elkind, because adolescents are so concerned with their own appearance and behavior, they assume that everyone else is, too. Wherever they are, whatever they are doing, they think that all eyes are on them, scrutinizing their every blemish or social misstep. This dimension of adolescent egocentrism, like the personal fable, has been found to become stronger across adolescence for boys but not girls (P. D. Schwartz et al., 2008).

In their middle teens, adolescents often begin to agonize over the contradictions in their behavior and characteristics. They tend to become introspective and concerned with the question “Who am I?” (Broughton, 1978). Their concern with this question is reflected in the following composite self-description of a 15-year-old:

What am I like as a person? You’re probably not going to understand. I’m complicated! With my really close friends, I am very tolerant, I mean I’m understanding and caring. With a group of friends I’m rowdier. I’m also usually friendly and cheerful, but I can be pretty obnoxious and intolerant if I don’t like how they’re acting.…I really don’t understand how I can switch so fast from being cheerful with my friends, then coming home and feeling anxious, and then getting frustrated and sarcastic with my parents. Which one is the real me?

(Quoted in Harter, 1999, p. 67)

445

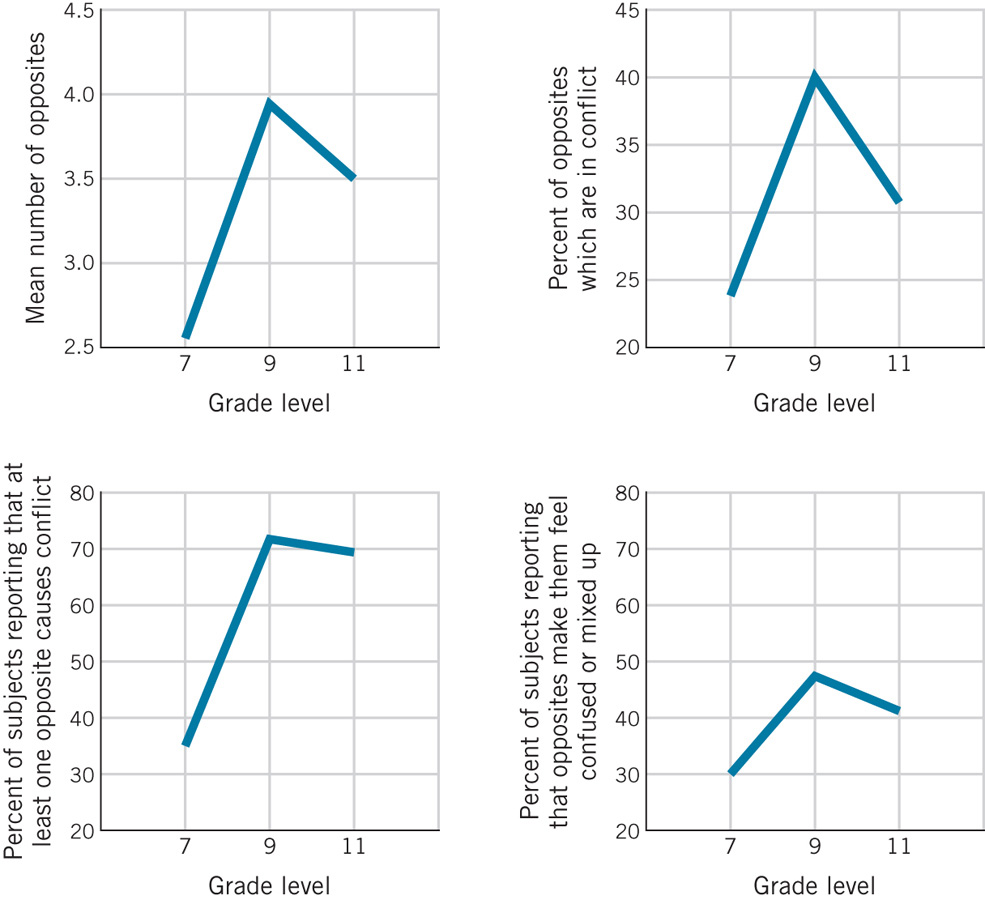

Although adolescents in their middle teens are better than younger adolescents at identifying contradictions in themselves (see Figure 11.2) and often feel conflicted about these inconsistencies, most still do not have the cognitive skills needed to integrate their recognition of these contradictions into a coherent conception of self. As a consequence, adolescents of this age often feel confused and concerned about who they really are. As one teen put it, “It’s not right, it should all fit together in one piece!” (Harter, 1999, p. 71; Harter et al., 1998).

In late adolescence and early adulthood, the individual’s conception of self becomes both more integrated and less determined by what others think. Both of these shifts are captured by Harter’s composite representation of a high school senior:

I’d like to be an ethical person who treats other people fairly. That’s the kind of lawyer I’d like to be, too. I don’t always live up to that standard; that is, sometimes I do something that doesn’t feel that ethical. When that happens I get a little depressed because I don’t like myself as a person. But I tell myself that it’s natural to make mistakes, so I don’t really question the fact that deep down inside, the real me is a moral person. Basically, I like who I am.…Being athletic isn’t that high on my own list of what is important, even though it is for a lot of the kids in our school. But I don’t really care what they think anymore. I used to, but now what I think is what counts. After all, I have to live with myself as a person and to respect that person, which I do now, more than a few years ago.

(Quoted in Harter, 1999, p. 78)

As in the case of this prototypical senior, older adolescents’ conceptions of self frequently reflect internalized personal values, beliefs, and standards. Many of these were instilled by others in the child’s life but are now accepted and generated by adolescents as their own. Thus, older adolescents place less emphasis on what other people think than they did at younger ages and are more concerned with meeting their own standards and with their future self—what they are becoming or are going to be (Harter, 1999, 2012; Higgins, 1991).

Older adolescents are also more likely to have the cognitive capacity to integrate opposites or contradictions in the self that occur in different contexts or at different times (Higgins, 1991). They may explain contradictory characteristics in terms of the need to be flexible, and may view variations in their behavior with different people as “adaptive” because one cannot act the same with everyone. Similarly, they may integrate changes in emotion under the characteristic “moody.” Moreover, they are likely to view their contradictions and inconsistencies as a normal part of being human, which likely reduces feelings of conflict and upset.

Whether older adolescents are able to successfully integrate contradictions in themselves likely depends not only on their own cognitive capacities but also on the help they receive from parents, teachers, and others in understanding the complexity of personalities. The support and tutelage of others in this regard allow adolescents to internalize values, beliefs, and standards that they feel committed to and to feel comfortable with who they are (D. Hart & Fegley, 1995; Harter, 1999, 2012).

446

Identity in Adolescence

identity versus identity confusion the psychosocial stage of development, described by Erikson, that occurs during adolescence. During this stage, the adolescent or young adult either develops an identity or experiences an incomplete and sometimes incoherent sense of self.

Clearly, the question “Who am I?” is a central and often disturbing one for many adolescents. It is also a question that, for many older adolescents, expands well beyond the issue of multiple selves and inconsistent behavior. As they begin to approach adulthood, adolescents must begin to develop a sense of personal identity that incorporates numerous aspects of self, including their values, their belief systems, their goals for the future, and, for some, their sexual identity.

identity achievement an integration of various aspects of the self into a coherent whole that is stable over time and across events

As noted in Chapter 9, Erik Erikson argued that the resolution of these many identity issues is the chief developmental task in adolescence. He referred to the resolution of these issues as the crisis of identity versus identity confusion. In his view, the challenge is as follows: “From among all possible and imaginable relations, [the person] must make a series of ever-narrowing selections of personal, occupational, sexual, and ideological commitments” (1968, p. 245). Successful resolution of this crisis results in identity achievement—that is, an integration of various aspects of the self into a coherent whole that is stable over time and across events.

Erikson’s Theory of Identity Formation

identity confusion an incomplete and sometimes incoherent sense of self that often occurs in Erikson’s stage of identity versus identity confusion

According to Erikson, adolescents who fail to attain identity achievement can experience one of several negative outcomes. One such outcome is identity confusion, an incomplete and sometimes incoherent sense of self that may cause the adolescent to feel lost, isolated, and depressed. Erikson suggested that some form of identity confusion is very common in adolescence and that it generally lasts for a relatively short time, although, according to Erikson, it sometimes persists and turns into a more severe psychological disturbance.

447

identity foreclosure premature commitment to an identity without adequate consideration of other options

Another negative outcome related to the struggle for identity can arise if adolescents commit themselves to an identity prematurely, that is, without adequately considering alternative possibilities. This identity choice is called identity foreclosure. An example of this category might be a 17-year-old who quits school and goes to work in a dead-end job because he or she does not envision any other options, or a young adolescent who, never considering other available career tracks, decides to become a doctor simply because his or her parent is one.

negative identity identity that stands in opposition to what is valued by people around the adolescent

A different self-defeating outcome of the search for an identity is a negative identity, one that is chosen because it represents the opposite of what is valued by people around the adolescent. A typical example would be a minister’s child’s willfully engaging in blatant immoral behavior, or a professor’s child’s rebelliously dropping out of high school with no occupational goal in mind. For some adolescents, Erikson suggested, taking on a negative identity is a way of getting noticed by significant others when more conventional attempts have failed.

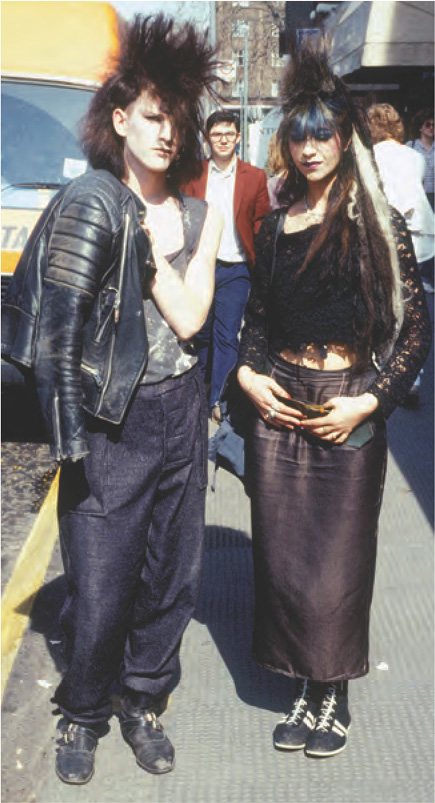

psychosocial moratorium a time-out during which the adolescent is not expected to take on adult roles and can instead pursue activities that may lead to self-discovery

Erikson (1968) argued that because of all the “possible and imaginable” role options that are available in modern society, attaining identity achievement is highly complex and difficult. In light of the negative consequences of failing to achieve a coherent identity, he proposed the importance of a psychosocial moratorium—a time-out period during which the adolescent is not expected to take on adult roles and is free to pursue activities that lead to self-discovery. During this period, adolescents can try out new looks, new ways of acting, new ideas about what they want to do for a living, and so forth.

Although Erikson argued that this period of experimentation is important to adolescents’ finding the best identity for themselves, a moratorium of this sort is possible or acceptable only in some cultures. Even then, it is often a luxury reserved for the middle and upper classes (i.e., those can who afford the moratorium provided by the college years). If adolescents must work full time to help support their families and themselves, many identity options will be closed to them because of limits on their time and schooling. In addition, in traditional societies where there are few role choices available, a moratorium is unheard of and unnecessary: children know from a very young age what their adult identity will be, and people generally live their lives in the same manner as their parents have.

Research on Identity Formation

identity-diffusion status a category of identity status in which the individual does not have firm commitments and is not making progress toward them

Following up on Erikson’s depiction of identity formation, a number of researchers looked for ways to measure the identity status of adolescents and to trace the outcome of the various statuses proposed by Erikson. The method most often used for this purpose was devised by James Marcia (1980). In this method, study participants are interviewed to determine the extent of their exploration of, and commitment to, issues related to occupation, ideology (e.g., religion, politics), and sexual behavior. On the basis of their responses, they are classified into one of the following four categories of identity status:

foreclosure status a category of identity status in which the individual is not engaged in any identity experimentation and has established a vocational or ideological identity based on the choices or values of others

Identity-diffusion status. The individual does not have firm commitments regarding the issues in question and is not making progress toward developing them.

Identity-diffusion status. The individual does not have firm commitments regarding the issues in question and is not making progress toward developing them.

Foreclosure status. The individual has not engaged in any identity experimentation and has established a vocational or ideological identity based on the choices or values of others.

Foreclosure status. The individual has not engaged in any identity experimentation and has established a vocational or ideological identity based on the choices or values of others.

Moratorium status. The individual is exploring various occupational and ideological choices and has not yet made a clear commitment to them.

Moratorium status. The individual is exploring various occupational and ideological choices and has not yet made a clear commitment to them.

moratorium status a category of identity status in which the individual is in the phase of experimentation with regard to occupational and ideological choices and has not yet made a clear commitment to them

Identity-achievement status. The individual has achieved a coherent and consolidated identity based on personal decisions regarding occupation, ideology, and the like. The individual believes that these decisions were made autonomously and is committed to them.

Identity-achievement status. The individual has achieved a coherent and consolidated identity based on personal decisions regarding occupation, ideology, and the like. The individual believes that these decisions were made autonomously and is committed to them.

More recently, researchers have delineated some additional distinctions in identity status. They propose, for example, that, during the moratorium, certain individuals explore possible commitments in two different ways. Some may explore them in breadth, trying out a variety of candidate identities before choosing one (Luyckx, Goossens, & Soenens, 2006; Luyckx, Goossens et al., 2006). For example, a person might consider being a musician, artist, or historian. (This type of exploration is similar to Marcia’s notion of moratorium.) Others may make an initial commitment and explore it in depth, through continuous monitoring of current commitments in order to make them more conscious (Meeus et al., 2010). Thus, they may try out various types of art (painting, sculpture) before committing to being an artist.

identity-achievement status a category of identity status in which, after a period of exploration, the individual has achieved a coherent and consolidated identity based on personal decisions regarding occupation, ideology, and the like. The individual believes that these decisions were made autonomously and is committed to them.

Researchers using methods similar to Marcia’s have found that most young adolescents seem to be in identity diffusion or identity foreclosure and that the percentage of youth in moratorium status is highest at ages 17 to 19 (Nurmi, 2004; Waterman, 1999). In the course of adolescence and early adulthood, individuals generally progress slowly toward identity achievement (Kroger et al., 2010; Meeus, 2011). The most typical sequences of change appear to be from diffusion → early foreclosure → achievement, or from diffusion → moratorium → closure → achievement; few move in the opposite direction (Meeus, 2011). There is little evidence that many adolescents have the kind of sustained identity confusion that Erikson maintained could lead to severe psychological disturbance (Meeus, 2011).

Researchers generally have found that, at least in modern Western societies, the identity status of adolescents and young adults is related to their adjustment, social behavior, and personality. Those who have made a commitment, whether through foreclosure or identity achievement, tend to be emotionally stable and high in self-esteem (Crocetti et al., 2008), low in depression and anxiety, and extroverted and agreeable (Luyckx et al., 2005; Luyckx et al., 2006; Meeus, 1996). Young adults who explore possible commitments more in depth than in breadth tend to be extroverted, agreeable, and conscientious (reliable, regulated), whereas those who explore more in breadth tend to be prone to negative emotionality but open to experience (Dunkel & Anthis, 2001; Luyckx et al., 2006). Individuals who have made commitments through foreclosure tend to be low on substance use (Luyckx et al., 2005) and aggression (Crocetti et al., 2008; Luyckx et al., 2008). In contrast, adolescents who are in moratorium, especially when they are experimenting in breadth, seem to be relatively likely to take drugs or to have unprotected sex (J. T. Hernandez & DiClemente, 1992; R. M. Jones, 1992; Luyckx, Goossens et al., 2006).

Influences on Identity Formation

A number of factors influence adolescents’ identity formation. One key factor is the approach parents take with their offspring. Adolescents who experience warmth and support from parents tend to have a more mature identity and less identity confusion (Meeus, 2011; S. J. Schwartz et al., 2009). In addition, parents tend to react with support when young college students explore in depth and make identity commitments (Beyers & Goossens, 2008), and this support may reinforce their children’s choices. Youths who are subject to parental psychological control tend to explore in breadth and are lower in making commitment to an identity (Luyckx et al., 2007). Adolescents are also more likely to explore identity options rather than go into foreclosure if they have at least one parent who encourages in them both a sense of connection with the parent and a striving for autonomy and individuality (Grotevant, 1998).

449

Identity formation is also influenced by both the larger social context and the historical context (Bosma & Kunnen, 2001). As already noted, adolescents from poor communities may have fewer career options because of low-quality schooling, financial limitations, and a lack of career information and role models. Such limitations likely affect some aspects of these adolescents’ identity formation.

The historical context plays a role in identity formation as well, because of the changes it brings about in identity options over time. Until a few decades ago, for instance, most adolescent girls focused their search for identity on the goal of marriage and family. Even in developed societies, few career opportunities were available to women. Today, women in many cultures are more likely to base their identity on both family and career. Thus, familial, individual, socioeconomic, historical, and cultural factors all contribute to identity development.

review:

Children’s self-conceptions change greatly with age, shifting from being very concrete—based on physical characteristics and overt behavior—to being based on internal qualities and the nature of one’s relationships with others. Young children tend to view themselves in uniformly positive ways and to overestimate their abilities. Older children are more likely to evaluate themselves on their general level of competence and to assess their own strengths and weaknesses realistically. In late childhood, children increasingly incorporate others’ perceptions of themselves into their self-image, and, with age, their conceptions of self also become much more complex and integrated.

Adolescents’ self-conceptions are more abstract than younger children’s and include the existence of different selves in different contexts. Young adolescents usually are not upset when they perceive discrepancies in their behavior and characteristics across contexts. However, according to Elkind, many young adolescents do develop a form of egocentrism that expresses itself as the “personal fable” and the critical “imaginary audience.” In mid-adolescence, teenagers often agonize over the discrepancies they see in themselves and tend to become concerned with the question “Who am I?” and with what others think of them. In late adolescence and early adulthood, concepts of the self become much more integrated and are more likely to include personal attributes that reflect internalized personal values, beliefs, and standards.

According to Erikson, adolescence is the time of the crisis of identity versus identity confusion, in which the young person must form an identity by making a series of ever-narrowing selections of personal, occupational, sexual, and ideological commitments. Exploration of choices relevant to one’s identity, especially exploration in depth, appears to be a healthy option in Western cultures but may not be a viable one in some cultures and subcultures. Most youths eventually move toward identity achievement, some with more exploration than others; this process is usually slow, and youths are fairly stable in their identity status over time. How and when young people construct their identity are affected by a variety of influences, ranging from personal and familial factors to cultural and historical ones.