Changes in Families in the United States

The family in the United States has changed dramatically since the middle of the twentieth century. For example, from the 1950s to 2008, the median age at which people first married rose from age 20 to nearly 25.6 for women and from age 23 to over 27.4 for men (Cherlin, 2010; Goodwin, McGill, & Chandra, 2009). Over this same period, the economic arrangement of the U.S. family also changed quite strikingly. In 1940, the father was the breadwinner and the mother was a full-time homemaker in 52% of nonfarm families (D. J. Hernandez, 1993). In contrast, in 2009 about 74% of mothers with children younger than 15 worked at least part time outside the home (Kreider & Elliott, 2010).

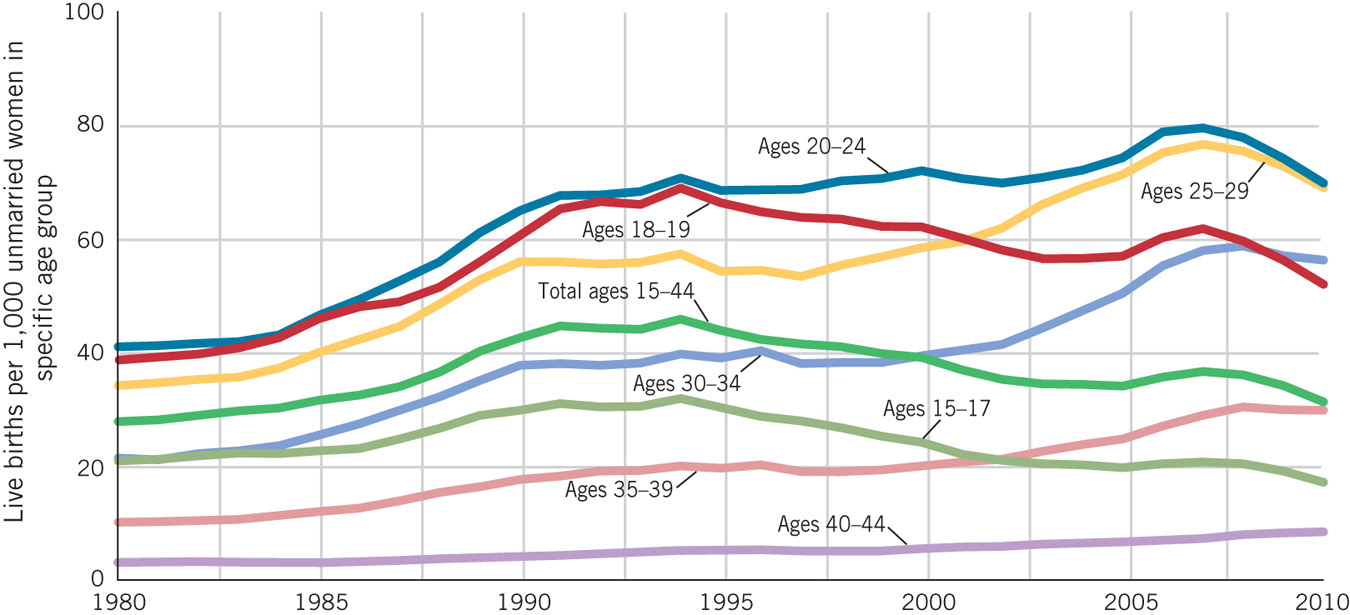

A third change that occurred in the family, partly as a result of the two just mentioned, was that the average age at which women bore children increased, especially within marriages. The mean age of first-time motherhood rose from 21.4 in 1970 to 25.4 in 2010. At the same time, births to mothers between ages 15 and 19 declined, dropping from 36% of total births in 1970 to 9.2% in 2010, the lowest rate since 1946 (J. A. Martin et al., 2012) (see Box 12.3).

486

Two of the most far-reaching changes in the U.S. family in the past half century have been the upsurge in divorce and the increase in the number of children born to unwed mothers. The divorce rate more than doubled between 1960 and 1980 and was between 40% and 50% in 2010 (Cherlin, 2010; Coltrane, 1996). The rise in out-of-wedlock births began in the 1980s. In 1980, 18% of all births were to unmarried women; in 2009, the figure was 41%, including 94% of births for 15- to 17-year-olds (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011; see Figure 12.4). However, it is important to note that about half the unmarried women who give birth are cohabiting with the fathers of their children (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008).

Box 12.3: individual differences: Adolescents as Parents

Childbearing in adolescence is a common occurrence in the United States. Among 15- to 17-year-olds in 2010, the rate of births was 17.3 per 1000 females (J. A. Martin et al., 2012). This rate, a decline of 55% from 1991 (which was the peak year for such births), was the lowest rate in the seven decades for which national data are available. This decline is likely due in part to the greater availability of birth control and abortions. Nevertheless, the current rate is still much higher than that in other industrialized countries (R. L. Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998).

A number of factors affect U.S. girls’ risk for childbearing during adolescence. Two factors that reduce the risk are living with both biological parents and being involved in school activities and religious organizations (B. J. Ellis et al., 2003; K. A. Moore et al., 1998). Factors that substantially increase the risk include being raised in poverty by a single or adolescent mother (R. L. Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; J. B. Hardy et al., 1998), low school achievement and dropping out of school (Freitas et al., 2008), significant family problems (e.g., death of a parent, drug or alcohol abuse in the family; Freitas et al., 2008), and having an older adolescent sibling who is sexually active or is already a parent (East & Jacobson, 2001; B. C. Miller, Benson, & Galbraith, 2001).

For young adolescent girls, having a mother who is cold and uninvolved may increase the risk of their becoming pregnant in later adolescence. In part, this may be because girls whose mothers fit this pattern tend to do poorly in school and hang out with peers who get into trouble, which often leads to risk taking and pregnancy (Scaramella et al., 1998). In fact, girls who are at risk for becoming mothers as teenagers tend to have many friends who are sexually active (East, Felice, & Morgan, 1993; Scaramella et al., 1998). It is likely that girls’ willingness to engage in sex is influenced by its acceptability in their group of friends.

Having a child in adolescence is associated with many negative consequences for both the adolescent mother and the child (Jaffee, 2002). Motherhood curtails the mother’s opportunities for education, career development, and normal relationships with peers. Even if teenage mothers marry, they are very likely to get divorced and to spend many years as single mothers (R. L. Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; M. E. Lamb & Teti, 1991; M. R. Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). In addition, adolescent mothers often have poor parenting skills and are more likely than older mothers to provide low levels of verbal stimulation to their infants, to expect their children to behave in ways that are beyond their years, and to neglect and abuse them (Culp et al., 1988; Ekéus, Christensson, & Hjern, 2004; M. E. Lamb & Ketterlinus, 1991).

Given these deficits in parenting, it is not surprising that children of teenage mothers are more likely than children of older mothers to exhibit disorganized attachment status, low impulse control, problem behaviors, and delays in cognitive development in the preschool years and thereafter. As adolescents themselves, children born to teenagers have higher rates of academic failure, delinquency, incarceration, and early sexual activity than do adolescents born to older mothers (R. L. Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; M. R. Moore & Brooks-Gunn, 2002; Wakschlag et al., 2000). Not surprisingly, they also tend to have less education, income, and life satisfaction as young adults (Lipman et al., 2011).

This does not mean that all children born to adolescent mothers are destined to poor developmental outcomes. Those whose mothers have more knowledge about child development and parenting and who exhibit more authoritative parenting than most teen mothers do tend to display fewer problem behaviors and better intellectual development (L. Bates, Luster, & Vandenbelt, 2003; C. L. Miller et al., 1996). In addition, those who experience a positive mother–child relationship, including consistent and sensitive parenting, appear more likely to stay in school and obtain employment in early adulthood (Jaffee et al., 2001). Supportive parents and other relatives are also likely to provide child care so that young mothers have the opportunity to continue their schooling.

487

A number of factors likewise affect adolescent males’ risk for becoming fathers. Chief among these are being poor, being prone to substance abuse and behavioral problems, being involved with deviant peers, and having a police record (Fagot et al., 1998; Miller-Johnson et al., 2004; D. R. Moore & Florsheim, 2001).

Many young unmarried or absent fathers see their children regularly, at least during the first few years, but rates of contact decrease over time (R. L. Coley & Chase- Lansdale, 1998; Marsiglio et al., 2000). In one study, 40% of adolescent fathers had no contact with their 2-year-old children (Fagot et al., 1998). Contact is less likely to be maintained when the unmarried noncohabiting father is an adolescent (M. Wilson & Brooks-Gunn, 2001). Young unmarried fathers remain more involved with their children if they have a warm, supportive relationship with the mother in the weeks after delivery and if the mother does not experience many stressful life events (particularly financial problems) during and soon after the pregnancy (Cutrona et al., 1998). They are also more likely to be involved with their infants if they have social support from their own parents for the parenting role, and if their level of stress related to fatherhood or other factors is low (Fagan, Bernd, & Whiteman, 2007).

The presence and support of the father can be beneficial to both the child and the mother. Adolescent mothers feel more competent as a parent and less likely to be depressed when they are satisfied with the level of the father’s involvement (Fagan & Lee, 2010). The children of adolescent mothers fare better in their own adolescence if they have a good relationship with their biological father (or a stepfather), especially if he lives with the child. However, exposure to a fathering figure may have little beneficial effect on children of adolescent mothers if the father–child relationship is not positive or the father figure has a criminal history (Furstenberg & Harris, 1993; Jaffee et al., 2001).

Due both to the increase in divorce and the increase in the birthrate among unmarried women, the percentage of children living with two married parents fell from 77% in 1980 to 66% in 2010. In 2010, 23% of children lived with only their mother, 3% lived with only their father, 4% lived with two unmarried parents, and 4% lived with neither parent—that is, with a grandparent, other relative, or a nonrelative (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011). Although people are more likely to divorce than in the past, most divorced people also remarry. Indeed, 54% percent of divorced women remarry after 5 years and 75% remarry within 10 years; these rates are even higher for women in the child-bearing years (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). Thus, the number of families including children from one or both parents’ prior marriages has increased substantially.

All these changes in the structure and composition of families have vast implications for the understanding of child development and family life. In the following sections, we will give detailed consideration to the impact of delayed parenthood, the effects of both divorce and remarriage on children’s development, and the issues surrounding maternal employment and child care. We will also consider an additional change in family structure that has recently received a good deal of public attention: the increase in the number of families with lesbian or gay parents.

488

Older Parents

In 1970, 1 of 100 first births were to mothers 35 or older; in 2010, the comparable figure was more than 1 in 7 (J. A. Martin et al., 2012). Within limits, having children at a later age has decided parenting advantages. Older first-time parents tend to have more education, higher-status occupations, and higher incomes than younger parents do. Older parents also are more likely to have planned the birth of their children and to have fewer children overall. Thus, they have more financial resources for raising a family. They are also less likely to get divorced within 10 years if they are married (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002).

Older parents also tend to be more positive in their parenting of infants than younger parents are—unless they already have several children. For example, one study found that, compared with people who became parents between the ages of 18 and 25, older mothers and fathers had lower rates of observed harsh parenting with their 2-year-olds, which, in turn, predicted fewer problem behaviors a year later (Scaramella et al., 2008). In another study, this one of mothers aged 16 to 38 who had recently given birth, older mothers expressed greater satisfaction with parenting and commitment to the parenting role, displayed more positive emotion toward the baby, and showed greater sensitivity to the baby’s cues. However, these positive outcomes did not extend to mothers who already had two or more children. Perhaps because they had less energy to deal with so many children, these mothers tended to exhibit less positive affect and sensitive behavior with their infants than did younger mothers with two or more other children (Ragozin et al., 1982).

Men who delay parenting until approximately age 30 or later are likewise more positive about the parenting role than are younger fathers (Cooney et al., 1993; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2000a). On average, they tend to be more responsive, affectionate, and cognitively and verbally stimulating with their infants. They are also more likely to provide a moderate amount of child care (Neville & Parke, 1997; NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2000a; Volling & Belsky, 1991). These differences may be partly due to older fathers’ more secure establishment in their careers, allowing them to focus on their role as father and to be more flexible in their beliefs about acceptable roles and activities for fathers (Coltrane, 1996; Parke & Buriel, 1998).

489

Divorce

In 2012, 5.4 million U.S. children lived with only their divorced mother, 1.3 million children lived only with their divorced father, and several million others lived in reconstituted families (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). Moreover, about 40% of remarriages involving children end in divorce in 10 years (Bramlett & Mosher, 2002). Thus, the effects of divorce and remarriage on children are of great concern.

The Potential Impact of Divorce

Most experts agree that children of divorce are at greater risk for a variety of short-term and long-term problems than are most children who are living with both their biological parents. Compared with the majority of their peers in intact families, for example, they are more likely to experience depression and sadness, to have lower self-esteem, and to be less socially responsible and competent (Amato, 2001; Ge, Natsuaki, & Conger, 2006; Hetherington, Bridges, & Insabella, 1998). In addition, children of divorce, especially boys, may be prone to higher levels of externalizing problem behaviors such as aggression and antisocial behavior, both soon after the divorce and years later (Burt et al., 2008; Hartman, Magalhães, & Mandich, 2011; Malone et al., 2004). Problems such as these may contribute to the drop in academic achievement that children of divorce often exhibit (Potter, 2010). Adolescents whose parents divorce exhibit a greater tendency toward dropping out of school, engaging in delinquent activities and substance abuse, and having children out of wedlock (Amato & Keith, 1991; Hetherington et al., 1998; Simons & Associates, 1996; Song, Benin, & Glick, 2012).

As adults, children from divorced and remarried families are at greater risk for divorce than are their peers from intact families (Bumpass, Martin, & Sweet, 1991; Mustonen et al., 2011; Rodgers, Power, & Hope, 1997). Within this group, women, but not men, appear to also be at risk for poorer-quality intimate relationships; lower self-esteem; and lower satisfaction with social support from friends, family members, and other people (Mustonen et al., 2011). Being less likely to have completed high school or college, children of divorce often earn lower incomes in early adulthood than do their peers from intact families (Hetherington, 1999; Song et al., 2012). As adults, they are also at slightly greater risk for serious emotional disorders such as depression, anxiety, and phobias (Chase-Lansdale, Cherlin, & Kiernan, 1995).

Despite all these greater risks, most children whose parents divorce do not suffer significant, enduring problems as a consequence (Amato & Keith, 1991). In fact, although divorce usually is a very painful experience for children, the differences between children from divorced families and children from intact families in terms of their psychological and social functioning are small overall (e.g., Burt et al., 2008). In addition, these differences often reflect an extension of the differences in the children’s and/or their parents’ psychological functioning that existed for years prior to the divorce (Clarke-Stewart et al., 2000; Emery & Forehand, 1994).

490

Factors Affecting the Impact of Divorce

A variety of interacting factors seem to predict whether the painful experiences of divorce and remarriage will cause children significant or lasting problems. The question here is one of individual differences: Why do some children of divorce fare better than others?

Parental conflict One influence on children’s adjustment to divorce is the level of parental conflict prior to, during, and after the divorce (Amato, 2010; Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1996). In fact, the level of parental conflict may predict the outcomes for children more than the divorce itself does. Not only is parental conflict distressing for children to observe, but it also may cause them to feel insecure about their own relationships with their parents, even making them fear that their parents will desert them or stop loving them (Davies & Cummings, 1994; Grych & Fincham, 1997). In addition, when there is parental conflict, fathers tend to have lower-quality relationships with their children, which may contribute to children’s adjustment problems (Pruett et al., 2003). In contrast, when parents are cooperative and communicate with each other, children exhibit fewer behavior problems and are closer with their nonresidential father (Amato, 2010).

Conflict between parents often increases when the divorce is being negotiated and may continue for years after the divorce. This ongoing conflict is especially likely to have negative effects on children if they feel caught in the middle of it, as when they are forced to act as intermediaries between their parents or to inform one parent about the other’s activities. Similar pressures may arise if children feel the need to hide from one parent information about, or their loyalty to, the other parent—or if the parents inappropriately disclose to them sensitive information about the divorce and each other. Adolescents who feel that they are caught up in their divorced parents’ conflict are at increased risk for being depressed or anxious and for engaging in problematic behavior such as drinking, stealing, cheating at school, fighting, or using drugs (Afifi et al., 2007, 2008, 2009; Afifi & McManus 2010; Buchanan, Maccoby, & Dornbusch, 1991; Kenyon & Koerner, 2008).

Stress A second factor that affects children’s adjustment to divorce is the stress experienced by the custodial parent and children in the new family arrangement. Not only must custodial parents juggle household, child-care, and financial responsibilities that usually are shared by two parents, but they often must do so isolated from those who might otherwise help. This isolation typically occurs when custodial parents have to change their residence and lose access to established social networks, or when friends and relatives—especially in-laws—take sides in the divorce and turn against them. In addition, custodial mothers usually experience a substantial drop in their income, and this financial stress is often associated with problems in their physical health (Wickrama et al., 2006). Given that some of these stressors are similar to those experienced by single parents more generally, it is no surprise that the quality of parenting, as well as children’s adjustment, tends to be highest when the parents are married and the biological parents of the children (S. L. Brown & Rinelli, 2010; Gibson-Davis & Gassman-Pines, 2010; Magnuson & Berger, 2009).

As a result of all these factors, the parenting of newly divorced mothers, compared with that of mothers in two-parent families, often tends to be characterized by more irritability and coercion and less warmth, emotional availability (e.g., parental sensitivity, structuring, nonintrusiveness, and nonhostility), consistency, and supervision of children (Hetherington, 1993; Hetherington et al., 1998; Simons & Johnson, 1996; K. E. Sutherland, Altenhofen, & Biringen, 2012). This is unfortunate because children tend to be most adjusted during and after the divorce if their custodial parent is supportive, emotionally available, and uses authoritative parenting (Altenhofen, K. E. Sutherland, & Biringen, 2010; DeGarmo, 2010; Hetherington, 1993; Simons & Associates, 1996; Steinberg et al., 1991).

491

Making parenting even more difficult for the mother, noncustodial fathers often are permissive and indulgent with their children (Hetherington, 1989; Parke & Buriel, 1998), increasing the likelihood that children will resent and resist their mother’s attempts to control their behavior. (On an optimistic note, intervention efforts among divorced mothers and children that focus on improving mother–child interactions and establishing the mother’s use of consistent discipline have been found to enhance the quality of the mother–child relationship and improve the children’s adjustment [McClain et al., 2010].)

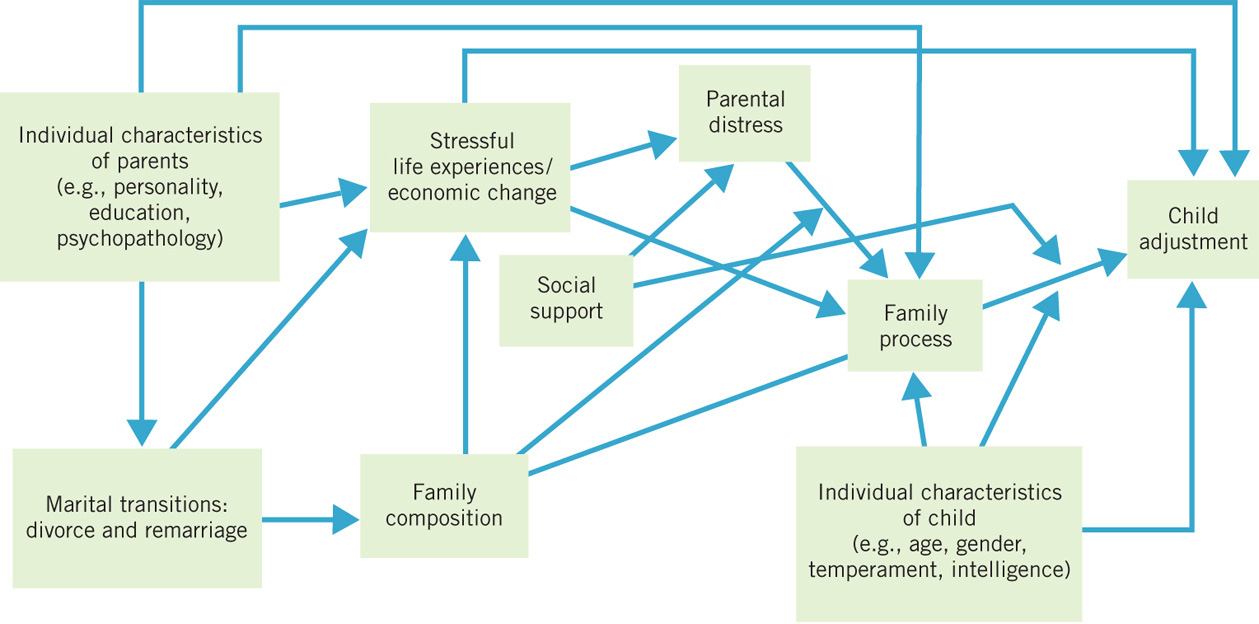

Thus, stressful life experiences during and after divorce often undermine the quality of parenting and of family interactions, which affects children’s adjustment (Ge et al., 2006). These stressful life experiences can also have a direct effect on the child’s adjustment (Figure 12.5). Having to change residences because of reduced household income, for example, may mean that at a time of high emotional vulnerability, a child also has to go through a wrenching transition to a new home, neighborhood, school, and peer group (Braver, Ellman, & Fabricius, 2003; Fabricius & Braver, 2006). Disruptions such as these due to reduced family income are likely to contribute to the problems some children of divorce experience, including declines in school performance (Sun & Li, 2011).

Age of the child An additional factor that influences the impact of divorce is the child’s age at the time of the divorce. Compared with older children and adolescents, younger children may have more trouble understanding the causes and consequences of divorce. They are especially more likely to be anxious about abandonment by their parents and to blame themselves for the divorce (Hetherington, 1989). As an 8-year-old boy explained, a year after his parents’ divorce:

492

My parents didn’t get along…. They used to argue about me all the time when they were married. I guess I caused them a lot of trouble by not wanting to go to school and all. I didn’t mean to make them argue….

(Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 1989, p. 73)

This boy firmly believed that he caused the divorce.

The following clinical report presents a picture of how divorce often affects young children:

When we first saw seven-year-old Ned, he brought his family album to the office. He showed us picture after picture of himself with his father, his mother, and his little sister. Smiling brightly, he said, “It’s going to be all right. It’s really going to be all right.” A year later, Ned was a sad child. His beloved father was hardly visiting and his previously attentive mother was angry and depressed. Ned was doing poorly in school, was fighting on the playground, and would not talk much to his mother.

(Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 1989, p. xvi)

Although older children and adolescents are better able to understand a divorce than are younger children, they are nonetheless particularly at risk for problems with adjustment, including poor academic achievement and negative relationships with their parents. Adolescents who live in neighborhoods characterized by a high crime rate, poor schools, and an abundance of antisocial peers are at especially high risk (Hetherington et al., 1998), most likely because the opportunities to get into trouble are amplified when there is only one parent—who most likely is at work during the day—to monitor the child’s activity. College students are less reactive to their parents’ divorce, probably because of their maturity and relative independence from the family (Amato & Keith, 1991). With regard to their parents’ remarriage, young adolescents appear to be more negatively affected than younger children. One possible explanation for this is that young adolescents’ struggles with the issues of autonomy and sexuality are heightened by the presence of a new parent who has authority to control them and is a sexual partner of their biological parent (Hetherington, 1993; Hetherington et al., 1992).

Contact with noncustodial parents Contrary to popular belief, the frequency of children’s contact with their noncustodial parent, usually the father, is not, in itself, a significant factor in their adjustment after divorce (Amato & Gilbreth, 1999; Trinder, Kellet, & Swift, 2008). Sadly, this is probably good news, because some data indicate that noncustodial fathers become increasingly uninvolved with their children over time, such that fewer than 50% of noncustodial fathers see their children more than once a year (Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 2002; Parke & Buriel, 1998). Moreover, it may be that the child’s adjustment after the divorce influences the father’s level of contact and involvement with the child rather than the other way around (Hawkins, Amato, & King, 2007).

What does seem to affect children’s adjustment after divorce is the quality of the contact with the noncustodial father: children who have contact with competent, supportive, authoritative noncustodial fathers show better adjustment and do better in school than children who have frequent but superficial or disruptive contact with their noncustodial fathers (Amato & Gilbreth, 1999; Hetherington, 1989; Hetherington et al., 1998; Whiteside & Becker, 2000). In contrast, contact with nonresidential fathers who have antisocial traits (e.g., who are vengeful, prone to getting into fights, manipulative, discourteous) predicts an increase in children’s noncompliance with their fathers (DeGarmo, 2010).

493

Less is known about noncustodial mothers. However, it is clear that they provide more emotional support for their children than noncustodial fathers do and are more likely to maintain contact through letters, phone calls, and overnight visits. The more the noncustodial mothers maintain such involvement with their children and are close to their children, the better adjusted their children are (Gunnoe & Hetherington, 2004; King, 2007).

The contribution of long-standing characteristics As noted earlier, it is important to recognize that the greater frequency of problem behaviors in children in divorced and remarried families may not be solely due to the divorce and remarriage. Rather, it sometimes may be related to characteristics of the parents or the children that existed long before the divorce. For example, the parents may have difficulty coping with stress or forming positive social relationships, as suggested by the fact that parents who divorce are more likely than undivorced parents to be depressed, alcoholic, or antisocial; to hold dysfunctional beliefs about relationships; or to lack skills for regulating conflict and negative emotion (Emery et al., 1999; Jocklin, McGue, & Lykken, 1996; Kurdek, 1993). Any one of these characteristics would be likely to undermine the quality of parenting the child receives.

The idea that the greater frequency of problem behaviors in children of divorce may be related to long-standing characteristics of the children themselves is supported by the finding that children of divorce tend to be more poorly adjusted prior to the divorce than are children from nondivorced families (Block, Block, & Gjerde, 1986; Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 2002). This difference may be due to stress in the home, poor parenting, or parental conflict prior to divorce. Alternatively or additionally, it may be due to the children’s own inherited characteristics, such as a lack of self-regulation or a predisposition to negative emotion (T. G. O’Connor et al., 2000). Such characteristics would not only underlie children’s adjustment problems but, when expressed in both children and their parents, would also increase the likelihood of divorce (Hetherington et al., 1998; Jocklin et al., 1996). Children with difficult personalities and limited coping capacities may also react more adversely to the negative events associated with divorce than would other children. However, although heredity seems to contribute to children’s adjustment after divorce through its effect on children’s characteristics, heredity probably is not the most important factor in how children cope with divorce (Amato, 2010).

Custody of Children After Divorce

In 2009, roughly 82% of children living with one divorced parent were living with their mother (Grall, 2011). However, parents sometimes have joint custody of their children. This arrangement is generally associated with better adjustment in children than is sole custody (Bauserman, 2002), but its effects depend in part on the degree of cooperation between ex-spouses. When parents cooperate with each other and keep the children’s best interests in mind, children are unlikely to feel caught in the middle (Maccoby et al., 1993). Unfortunately, mutually helpful parenting is not the norm (Bretherton & Page, 2004): researchers have found that once parents have been separated for a while, most either engage in conflict or do not deal much with each other (Amato, Kane, & James, 2011; Maccoby et al., 1993).

494

An Alternative to Divorce: Ongoing Marital Conflict

On the basis of the publicity given to the negative effects that divorce can have on children, some people have argued that it would be better for families if it were more difficult for parents to obtain a divorce. When considering this argument, it is important to realize that sustained marital conflict has negative effects on children at all ages. Infants and children can be harmed by marital conflict because it may cause parents to be less warm and supportive, undermining their emotional involvement with the child and the security of the early parent–child attachment (El-Sheikh & Elmore-Staton, 2004; Frosch, Mangelsdorf, & McHale, 2000; Sturge-Apple et al., 2006, 2012; Taylor et al., 2008). Preschoolers and older children are especially likely to feel threatened and helpless when there is ongoing parental conflict—more so if the conflict involves high levels of verbal and physical aggression (Davies, Cummings, & Winter, 2004; Grych, Harold, & Miles, 2003). Even adolescents often feel threatened by, and responsible for, parental conflict (Buehler et al., 2007).

Perhaps as a consequence of these negative effects, interparental conflict and aggression are associated with children’s and adolescents’ reduced attentional skills, negative emotion, behavioral problems, and abnormal cortisol responses to distress (Grych et al., 2004; Lindahl et al., 2004; Schermerhorn et al., 2010; Sturge-Apple et al., 2012; Towe-Goodman et al., 2011). All these outcomes are likely to be exacerbated if the sustained marital conflict leads—as it frequently does—to parental hostility toward the children themselves (Buehler et al., 1997; Harold & Conger, 1997).

Further complicating matters is the fact that the relation between marital conflict and children’s problem behavior seems to be partly due to genetic factors that affect both parents’ and children’s behavior (Harden et al., 2007; Schermerhorn et al. 2011) and partly due to the link between marital conflict and compromised parenting behavior (Ganiban et al., 2011). Consistent with the aforementioned pattern of relations, Amato and colleagues (1995) found that among children raised in high-conflict families, those whose parents divorced were better adjusted than those whose parents stayed together, whereas the reverse was true for low-conflict families.

Stepparenting

In 2009, 5.6 million children in the United States were living with a stepparent (Kreider & Ellis, 2011). For many children, the entry of a stepparent into the family is a very threatening event. As described by one long-term study, the child’s world is suddenly full of anxious questions:

What will this new man do for me? Will he threaten my position in the family? Will he interfere with my relationship with Mom and Dad?…Is he good for my mom? Will she be in a better mood? Will she treat me better?…Will my dad be angry? Will having a stepfather around make Dad want to visit me more or less?…Will Mom and Dad ever get remarried now that someone else is in the picture?

(Wallerstein & Blakeslee, 1989, p. 246)

The answers to specific questions like these obviously vary case by case. Nevertheless, investigators have found some general patterns in the adjustments that are required of both children and adults when a remarriage occurs.

495

Factors Affecting Children’s Adjustment in Stepfamilies

Children’s adjustment to living with a stepparent is influenced by a number of factors, including the child’s age at the time of the remarriage. Very young children tend to accept stepparents more easily than do older children and adolescents (Amato & Keith, 1991; Hetherington et al., 1989). In addition, children generally adjust better and do better academically when all the children are full siblings (Hetherington et al., 1999; Tillman, 2008). One indicator of this is the fact that, in adolescence, children born into blended families have higher rates of delinquency, depression, and detachment from school tasks and relationships than do full siblings living with their biological parents, perhaps because there may be more sibling conflict in blended families (Halpern-Meekin & Tach, 2008).

The challenges in stepfamilies may differ somewhat for families with stepfathers and those with stepmothers. Although most stepfathers want their new families to thrive, they generally feel less close to their stepchildren than do fathers in intact families (Hetherington, 1993). At first, stepfathers tend to be polite and ingratiating toward their stepchildren and are not as involved in monitoring or controlling them as are fathers in intact families (Kurdek & Fine, 1993). Nevertheless, on average, conflict between stepfathers and stepchildren tends to be greater than that between fathers and their biological offspring (Bray & Berger, 1993; Hakvoort et al., 2011; Hetherington et al., 1992, 1999), perhaps in part because stepfathers are more likely to see the children as burdens than their biological fathers are (A. O’Connor & Boag, 2010). It is thus not surprising that children with stepfathers tend to have higher rates of depression, withdrawal, and disruptive problem behaviors than do children in intact families (Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 1995).

Preadolescent girls in particular are likely to have problems with their step fathers. Often the difficulty arises from the fact that prior to the remarriage, divorced mothers have had a close, confiding relationship with their daughters, and the entry of the stepfather into the family disrupts this relationship. These changes can lead to resentment in the daughter and conflict with both her mother and the stepfather (Hetherington et al., 1992; Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 2002).

Despite these potential difficulties, the presence of an involved stepfather can bring benefits, including a substantial improvement in family finances and a welcome source of emotional support and assistance for the custodial parent. A new stepfather may be especially helpful both in controlling his stepson and in providing a male role model (Parke & Buriel, 1998). One sign of this is that the increase of delinquency associated with children of divorce is lessened if the adolescent’s parent remarries (Burt et al., 2008). Overall, with time, children often become as close to their stepfathers as they are to their nonresidential biological fathers, sometimes even closer (Falci, 2006), usually without affecting their relationship with the biological father (King, 2009). For adolescents, having a close relationship with both their stepfather and their biological father, and believing that they matter to both, is associated with better adolescent outcomes (Schenck et al., 2009).

Because there are decidedly fewer stepmothers than stepfathers, much less research has been devoted to their role as stepparents. However, it appears that stepmothers generally have more difficulty with their stepchildren than do stepfathers (Gosselin & David, 2007) and are at risk for depressive symptoms (D. N. Shapiro & Stewart, 2011). Often fathers expect stepmothers to take an active role in parenting, including monitoring and disciplining the child, although children frequently resent the stepmother’s being the disciplinarian and may reject her authority or accept it only grudgingly. This may help explain why stepmothers are more likely than biological mothers to feel resentment toward their children and view them as a burden (A. O’Connor & Boag, 2010). Despite these problems, when it is possible for stepmothers to use authoritative parenting successfully, stepchildren may be better adjusted (Hetherington et al., 1998). Indeed, children of both sexes are most adjusted in stepfamilies when their custodial parent is authoritative in his or her parenting style and the stepparent is warm and involved and supports the custodial parent’s decisions rather than trying to exert control over the children independently (Bray & Berger, 1993; Hetherington et al., 1998).

496

An additional factor in children’s adjustment in stepfamilies is the attitude of the noncustodial biological parent toward the stepparent and the level of conflict between the two (Wallerstein & Lewis, 2007). If the noncustodial parent has hostile feelings toward the new stepparent and communicates these feelings to the child, the child is likely to feel caught in the middle, increasing his or her adjustment problems (Buchanan et al., 1991). The noncustodial parent’s hostile feelings may also encourage the child to behave in a hostile or distant manner with the stepparent. Not surprisingly, children in stepfamilies fare best when the relations between the noncustodial parent and the stepparent are supportive and the relations between the biological parents are cordial (Golish, 2003). Thus, the success or failure of stepfamilies is affected by the behavior and attitudes of all involved parties.

Finally, the effects of restructuring the family may vary across racial and ethnic groups. In contrast to much of the research on European American families, for example, some research on African American families suggests that there are few differences in African American youths’ depression, self-esteem, and conflict-management skills in two-parent nuclear families and in stepfamilies. Because African American children often live in a single-parent home prior to living with a stepfather, the presence of a stepfather is likely to increase positive outcomes for children (Adler-Baeder et al., 2010).

Lesbian and Gay Parents

Another way that U.S. families have changed in recent decades is that more lesbian and gay adults are parents. Although the numbers of lesbian and gay parents cannot be estimated with confidence because many conceal their sexual orientation, the most likely figure seems to be between 1 and 5 million (C. J. Patterson, 2002). The 2000 Census reported that among individuals living in same-sex cohabiting partnerships, 33% of women and 22% of men had children living with them. However, because the Census survey did not ask specifically about sexual orientation, it is not clear what exactly can be inferred from these data (Cherlin, 2010).

Most children of lesbian or gay parents are born when their parents are in a heterosexual marriage or relationship. In many cases, the parents divorce when one parent comes out as lesbian or gay. In addition, an increasing number of single and coupled lesbians are choosing to give birth to children, often through the use of artificial insemination. Other lesbians or gay men choose to become foster or adoptive parents, although there sometimes are legal barriers to such adoptions. In some cases, gay men have opportunities to act as stepfathers to the biological children of their partners (C. J. Patterson, 2002; C. J. Patterson & Chan, 1997).

The question that concerns many people is whether children raised by gay and lesbian parents grow up to be different from other children. According to a growing body of research, they are, in fact, very similar in their development to children of heterosexual parents in terms of adjustment, personality, and relationships with peers (Farr et al., 2010; Gartrell & Bos, 2010; Golombok, Spencer, & Rutter, 1983; Wainright & Patterson, 2006, 2008). They are also similar in their sexual orientation and in the degree to which their behavior is gender-typed (J. M. Bailey et al., 1995; Fulcher, Sutfin, & Patterson, 2008; Golombok et al., 2003), as well as in their romantic involvements and sexual behavior as adolescents (Wainright, Russell, & Patterson, 2004). Perhaps surprisingly, children of lesbian and gay parents generally report low levels of stigmatization and teasing (Tasker & Golombok, 1995), although they sometimes feel excluded, or gossiped about, by peers (Bos & van Balen, 2008). This relatively low rate of difficulties with peers may be partly due to the fact that children of gay or lesbian parents frequently try to hide their parents’ sexual preference from their friends, largely because they fear being labeled by peers as gay or lesbian themselves (Bozett, 1987; Crosbie-Burnett & Helmbrecht, 1993).

497

As in families with heterosexual parents, the adjustment of children with lesbian and gay parents seems to depend on family dynamics, including the closeness of the parent–child relationship (Wainright & Patterson, 2008), how well the parents get along, parental supportiveness, regulated discipline, and the degree of stress parents experience in their parenting (Farr, Forssell, & Patterson, 2010; Farr & Patterson, 2013). In addition, children of lesbian parents are better adjusted when their mother and her partner are not highly stressed (R. W. Chan, Raboy, & Patterson, 1998), when they report sharing child-care duties evenly (C. J. Patterson, 1995), and when they are satisfied with the division of labor in the home (R. W. Chan et al., 1998). When gay adoptive fathers have low levels of social support and a less positive gay identity, they experience more stress regarding parenting and are more likely to have poor relationships with their children (Tornello et al., 2011)—responses that are likely to affect their children’s adjustment. In families with a gay father and his partner, a son’s happiness with his family life is related to the inclusion of the partner in family activities and the son’s having a good relationship with the partner as well as with his biological father (Crosbie-Burnett & Helmbrecht, 1993).

review:

The American family has changed dramatically in recent decades. Adults are marrying later and having children later; more children are born to single mothers; and divorce and remarriage are common occurrences.

Adolescent parents come disproportionately from impoverished backgrounds and are more likely than other teens to have behavioral and academic problems. Adolescent mothers tend to be less effective parents than older mothers, and their children are at risk for behavioral and academic problems and early sexual activity. In contrast, mothers who delay childbearing tend to be more responsive to their children than are mothers who have their first children at a younger age.

Parental divorce and remarriage have been associated with enduring negative outcomes, such as behavioral problems, for only a minority of children. The major factor contributing to negative outcomes for children of divorce is dysfunctional family interactions in which parents deal with each other in hostile ways and children feel caught in the middle. Parental depression and upset, as well as economic pressures and other types of stress associated with single parenting, often compromise the quality of parents’ interactions with each other and with their children.

498

Stepfamilies present special challenges. Conflict is common in stepfamilies, especially when the children are adolescents, and stepparents usually are less involved with their stepchildren than are biological parents. Children do best if all parents are supportive and use an authoritative parenting style.

An increasing number of children live in families in which at least one parent is openly lesbian or gay. There is no evidence that children raised by lesbian or gay parents are more likely to be lesbian or gay themselves or to differ from children of heterosexual parents in their adjustment.