Status in the Peer Group

As noted in the preceding section, older children and adolescents often are extremely concerned with their peer status: being popular is of great importance, and peer rejection can be a devastating experience. Rejection by peers is associated with a range of developmental outcomes for children, such as dropping out of school and problem behaviors, and these relations can hold independent of any effects of having, or not having, close friends (Gest et al., 2001). Because of the central role that peer relations play in children’s lives, developmental researchers have devoted a good deal of effort to studying the concurrent and long-term effects associated with peer status.

533

In this section, we will examine children’s status in the peer group, including how it is measured, its stability, the characteristics that determine it, and the long-term implications of being popular with, or being rejected by, peers.

Measurement of Peer Status

sociometric status a measurement that reflects the degree to which children are liked or disliked by their peers as a group

The most common method developmentalists use to assess peer status is to ask children to rate how much they like or dislike each of their classmates. Alternatively, they may ask children to nominate some of those whom they like the most and the least, or whom they do or don’t like to play with. The information from these procedures is used to calculate the children’s sociometric status, or peer acceptance—that is, the degree to which the children are liked or disliked by their peers as a group. The most commonly used sociometric system classifies children into one of five groups: popular, rejected, neglected, average, or controversial (see Table 13.3) (Coie & Dodge, 1988).

Characteristics Associated with Sociometric Status

Why are some children liked better than others? One obvious factor is physical attractiveness. From early childhood through adolescence, attractive children are much more likely to be popular, and are less likely to be victimized by peers, than are children who are unattractive (Langlois et al., 2000; Rosen, Underwood, & Beron, 2011; Vannatta et al., 2009). Athleticism is also related to high peer status, albeit more strongly for boys than for girls (Vannatta et al., 2009). Further affecting peer status is the status of one’s friends: having popular friends appears to boost one’s own popularity (Eder, 1985; Sabongui, Bukowski, & Newcomb, 1998). Beyond these simple determiners, sociometric status also seems to be affected by a variety of other factors, including children’s social behavior, personality, cognitions about others, and goals when interacting with peers.

534

Popular Children

popular (peer status) a category of sociometric status that refers to children or adolescents who are viewed positively (liked) by many peers and are viewed negatively (disliked) by few peers

Popular children—those who, in sociometric procedures, are predominantly nominated as liked by peers—tend to have a number of social skills in common. To begin with, they tend to be skilled at initiating interaction with peers and at maintaining positive relationships with others (Rubin et al., 2006). For example, when popular children enter a group of children who are already talking or playing, they first try to see what is going on in the group and then join in by talking about the same topic or engaging in the same activity as the group, rather than drawing unwarranted attention to themselves (Dodge et al., 1983; Putallaz, 1983).

At a broader level, popular children tend to be cooperative, friendly, sociable, helpful, and sensitive to others, and they are perceived that way by their peers, teachers, and adult observers (Dodge et al., 1997; Lansford et al., 2006; Newcomb, Bukowski, & Pattee, 1993; Rubin et al., 2006). They also regulate themselves well (N. Eisenberg et al., 1993; Kam et al., 2011), are not prone to intense negative emotions, and tend to have a relatively high number of low-conflict reciprocated friendships (Litwack, Wargo Aikins, & Cillessen, 2012).

Although popular children often are less aggressive overall than are rejected children (Newcomb et al., 1993), in comparison with children designated as average (i.e., those who receive an average number of both positive and negative nominations), they are less aggressive only with respect to aggression related to generalized anger, vengefulness, or satisfaction in hurting others (Dodge et al., 1990). With respect to assertive aggressiveness, including pushing and fighting, popular children often do not differ from average children (Newcomb et al., 1993). Highly aggressive children may even have high peer acceptance in some special cases, such as among adolescent males (but not females) who perform poorly in school (Kreager, 2007), in peer groups in which the popular members tend to be relatively aggressive (Dijkstra, Lindenberg, & Veenstra, 2008), or in classrooms that have a strong hierarchy in terms of peer status (Garandeau, Ahn, & Rodkin, 2011).

relational aggression a kind of aggression that involves excluding others from the social group and attempting to do harm to other people’s relationships; it includes spreading rumors about peers, withholding friendship to inflict harm, and ignoring peers when angry or frustrated or trying to get one’s own way.

On the question of aggression and popularity, it is important to differentiate between children who are popular in terms of sociometric, or social-preference, measures—that is, who are well liked by peers—and those who are perceived by peers as being popular or high status in the group. Although children who are well liked by peers tend not to be particularly aggressive, children who are perceived as having high status in the group—those who are often labeled “popular” by other children and often seen as “cool”—tend to be viewed as above average in aggression and use it to obtain their goals (P. H. Hawley, 2003; Kuryluk, Cohen, & Audley-Piotrowski, 2011; Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003). This association between aggression and perceived popularity, although seen to some degree even in preschool (Vaughn et al., 2003), is quite strong in early adolescence; indeed, high-status individuals, particularly girls, are likely to engage in relational aggression, such as excluding others from the group, withholding friendship to inflict harm, and spreading rumors to ruin a peer’s reputation (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; K. E. Hoff et al., 2009; Prinstein & Cillessen, 2003).

535

Especially if they are aware that they are perceived as popular, youth who are perceived as having high status tend to increasingly use relational and physical aggression across adolescence, perhaps because they tend to be arrogant and can get away with it (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Mayeux & Cillessen, 2008; A. J. Rose, Swenson, & Waller, 2004). By the middle-school years, children with the reputation of being popular sometimes start to shun less popular peers. As a result, they are considered “stuck-up,” “mean,” and “snobby” and begin to be viewed with ambivalence by their peers and sometimes even become resented or disliked (Closson, 2009; Mayeux, 2011; Merten, 1997; D. L. Robertson et al., 2010).

Rejected Children

rejected (peer status) a category of sociometric status that refers to children or adolescents who are liked by few peers and disliked by many peers

A majority of rejected children tend to fall into one of two categories: those who are overly aggressive and those who are withdrawn.

Aggressive-rejected children

According to reports from peers, teachers, and adult observers, 40% to 50% of rejected children tend to be aggressive. These aggressive-rejected children are especially prone to hostile and threatening behavior, physical aggression, disruptive behavior, and delinquency (Lansford et al., 2010; Newcomb et al., 1993; S. Pedersen et al., 2007; Rubin et al., 2006). When they are angry or want their own way, many rejected children also engage in relational aggression (Cillessen & Mayeux, 2004; Crick, Casas, & Mosher, 1997; Tomada & Schneider, 1997).

aggressive-rejected children a category of sociometric status that refers to children who are especially prone to physical aggression, disruptive behavior, delinquency, and negative behavior such as hostility and threatening others

Most of the research on the role of aggression in peer status is correlational, so it is impossible to know for certain whether aggression causes peer rejection or results from it. However, some research supports the view that frequent aggressive behavior often underlies rejection by peers. For example, observation of unfamiliar peers getting to know one another has shown that those who are aggressive become rejected over time (Coie & Kupersmidt, 1983). In addition, longitudinal research has shown that children who are aggressive, negative, and disruptive tend to become increasingly disliked by peers across the school year (S. A. Little & Garber, 1995; Maszk, Eisenberg, & Guthrie, 1999).

Nonetheless, other research suggests that the experience of rejection may trigger or increase children’s aggression. In an experimental study, 5th- and 6th-graders were led to believe that they had been entered in an online popularity contest and had been evaluated by peer judges on the basis of a personal photograph and information about their preferences and personality traits. They were then presented with their “peers’” evaluations—which were actually standardized assessments devised by the researchers to be either neutral or mostly negative and rejecting. After receiving their evaluations, the participants were given the opportunity to reduce the payments that would be made to the judges and to post negative comments about the judges on the contest’s website. Those youths who were rejected by the judges, compared with those who were not, imposed deeper cuts on judges’ payments and posted more negative comments about them on the website (Reijntjes, Thomaes et al., 2011). Taken together, these and other studies suggest that the relation between peer rejection and youths’ aggression is bidirectional—that aggression predicts more peer rejection over time and that more peer rejection predicts more aggression (Lansford et al., 2010).

536

As you have seen, however, not all aggressive children are rejected by their peers and some are even perceived as popular (Farmer et al., 2011; D. L. Robertson et al., 2010). Aggressive children sometimes develop a network of aggressive friends and are accepted in their peer group (Xue & Meisels, 2004), and some elementary school and preadolescent children who start fights and get into trouble are viewed as “cool” and are central in their peer group (K. E. Hoff et al., 2009; Rodkin et al., 2000, 2006). Many of these children are among those designated as controversial—liked by numerous peers and disliked by numerous others.

Withdrawn-rejected children

withdrawn-rejected children a category of sociometric status that refers to rejected children who are socially withdrawn, wary, and often timid

The second group of rejected children includes those who are withdrawn-rejected. These children, who make up 10% to 25% of the rejected category, are socially withdrawn and wary and, according to some research, are often timid and socially anxious (Booth-LaForce et al., 2012; Cillessen et al., 1992; Rubin et al., 2006). They frequently are victimized by peers, and many feel isolated and lonely (Booth-LaForce & Oxford, 2008; Rubin, Coplan, & Bowker, 2009; Woodhouse, Dykas, & Cassidy, 2012). Friendlessness, friendship instability, and exclusion in 5th grade predict increases in socially withdrawn behavior through 8th grade, whereas low peer exclusion in 5th grade predicts a decline in social withdrawal across time (Oh et al., 2008). Thus, as with aggression, social withdrawal may be both a cause and consequence of peer exclusion and rejection.

However, not all socially withdrawn children are rejected or socially excluded (Gazelle, 2008; Gazelle & Ladd, 2003). Rather, it is active isolates—withdrawn children who display immature, unregulated, or angry, defiant behavior such as bullying, boasting, and meanness—who are the most likely to be rejected by their peers. Research suggests that children who are withdrawn with peers but are relatively socially competent tend to be merely neglected—that is, they are not nominated as either liked or disliked by peers (Harrist et al., 1997). Similarly, children and adolescents who are simply not social and prefer solitary activities may not be especially prone to peer rejection (J. C. Bowker & Raja, 2011; Coplan & Armer, 2007).

537

Over the course of childhood, withdrawn behavior seems to become a more reliable predictor of peer rejection. By the middle to late elementary school years, children who are quite withdrawn stand out, tend to be disliked, and appear to become increasingly alienated from the group as time goes on (Rubin et al., 1998). In some cases, however, children who are not initially socially withdrawn have social isolation forced upon them as they progress through school (A. Bowker et al., 1998). That is, children who are disliked and rebuffed by peers, often because of their disruptive or aggressive behavior, may increasingly isolate themselves from the group even if they initially were not withdrawn (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990; Rubin et al., 1998).

Social cognition and social rejection

Rejected children, particularly those who are aggressive, tend to differ from more popular children in their social motives and in the way they process information related to social situations (Lansford et al., 2010). For example, rejected children are more likely than better-liked peers to be motivated by goals such as “getting even” with others or “showing them up” (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Rubin et al., 2006). As discussed in Chapter 9, they also are relatively likely to attribute malicious intent to others in negative social situations, even when the intent of others is uncertain or benign (Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Rejected children also have more trouble than other children do in finding constructive solutions to difficult social situations, such as wanting to take a turn on a swing when someone else is using it. When asked how they would deal with such situations, rejected children suggest fewer strategies than do their more popular peers, and the ones they suggest are more hostile, demanding, and threatening (Dodge et al., 2003; Harrist et al., 1997; Rubin et al., 1998). (Box 13.3 discusses programs designed to help rejected children gain peer acceptance.) Perhaps one reason rejected children are more likely to select inappropriate strategies is that their theory of mind is less developed than that of their better-liked peers, and they may therefore have greater difficulty understanding others’ feelings and thoughts (Caputi et al., 2012; see Chapter 7).

Neglected Children

neglected (peer status) a category of sociometric status that refers to children or adolescents who are infrequently mentioned as either liked or disliked; they simply are not noticed much by peers

As noted earlier, some withdrawn children are categorized as neglected because they are not nominated by peers as either liked or disliked (Booth-LaForce & Oxford, 2008). These children tend to be both less sociable and less disruptive than average children (Rubin et al., 1998) and are likely to back away from peer interactions that involve aggression (Coie & Dodge, 1988). Neglected children perceive that they receive less support from peers (S. Walker, 2009; Wentzel, 2003), yet they are not particularly anxious about their social interactions (Hatzichristou & Hopf, 1996; Rubin et al., 1998). In fact, other than being less socially interactive, neglected children display few behaviors that differ greatly from those of many other children (Bukowski et al., 1993; S. Walker, 2009). They appear to be neglected primarily because they are simply not noticed by their peers.

Controversial Children

controversial (peer status) a category of sociometric status that refers to children or adolescents who are liked by quite a few peers and are disliked by quite a few others

In some ways, the most intriguing group of children are controversial children, who, as indicated, are liked by numerous peers and disliked by numerous others. Controversial children tend to have characteristics of both popular and rejected children (Rubin et al., 1998). For example, they tend to be aggressive, disruptive, and prone to anger, but they also tend to be cooperative, sociable, good at sports, and humorous (Bukowski et al., 1993; Coie & Dodge, 1988). In addition, they are very socially active and tend to be group leaders (Coie et al., 1990). At the same time, controversial children tend to be viewed by peers as arrogant and snobbish (Hatzichristou & Hopf, 1996), which could explain why they are disliked by some peers even if they are perceived as having high status in the peer group (D. L. Robertson et al., 2010).

538

Box 13.3: applications: Fostering Children’s Peer Acceptance

Given the difficult and often painful outcomes commonly associated with a child’s being rejected or having few friends, a number of researchers have designed programs to help children in these categories gain acceptance from peers. Their approaches have varied according to what they believe to be the causes of social rejection, but a number of approaches have proved to be useful, at least to some degree.

social-skills training training programs designed to help rejected children gain peer acceptance; they are based on the assumption that rejected children lack important knowledge and skills that promote positive interaction with peers

One common approach involves social-skills training. The assumption behind this approach is that rejected children lack social skills that promote positive peer relations. These deficits are viewed as occurring at three levels (Mize & Ladd, 1990):

- Lack of social knowledge—Rejected children lack social knowledge regarding the goals, strategies, and normative expectations that apply in specific peer contexts. For example, children engaged in a joint activity usually expect a newcomer to the group to blend in slowly and not to begin immediately pushing his or her own ideas or wishes. Lacking an understanding of this, aggressive-rejected children are likely to barge in on a conversation or to try to control the group’s choice of activities. In contrast, a withdrawn- rejected child may not know how to start a conversation or contribute to the group’s activities when the opportunity arises.

- Performance problems—Some rejected children possess the social knowledge required for being successful in various peer contexts, but they may still act inappropriately because they are unable or unmotivated to use their knowledge to guide their performance.

- Lack of appropriate monitoring and self-evaluation—To behave in a way that is consistent with the interests and actions of their peers, children need to monitor their own and others’ social behavior. Such monitoring requires them to accurately interpret social cues regarding what is occurring, what others are feeling and thinking, and how their own behavior is being perceived. Rejected children often cannot engage in such monitoring and thus cannot modify their behavior in appropriate ways.

To help children overcome such deficits, some social-skills training programs teach children to pay attention to what is going on in a group of peers and help them develop skills related to participating with peers. Interventions may include coaching and rehearsing children on how to start a conversation with an unfamiliar peer, how to compliment a peer, how to smile and offer help, and how to take turns and share materials (Oden & Asher, 1977). In other interventions, the emphasis is primarily on teaching children to think about alternative ways to achieve a goal, evaluate the consequences of each alternative, and then select an appropriate strategy. Children may be asked to think about or act out a situation in which they are excluded or teased by peers and to come up with various strategies for handling the situation. The children are then helped to evaluate the strategies and to understand the specific costs and benefits of each (e.g., Coleman, Wheeler, & Webber, 1993).

Recent forms of this sort of program are often multifaceted, including such components as communication skills, anger management, and training in perspective taking (Reid, Webster-Stratton, & Hammond, 2007; Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Stoolmiller, 2008). Their primary focus is on helping children to better understand and communicate about their own and others’ emotions and to regulate their behavior (Domitrovich, Cortes, & Greenberg, 2007; Izard et al., 2008; P. C. McCabe & Altamura, 2011), although training in social-skill strategies also usually occurs to some degree. The general assumption underlying these programs is that children act in more appropriate ways and, consequently, are better liked if their behavior takes into account the feelings of others and is modulated in a manner that is both sensitive and socially appropriate to those feelings.

A notable example of this approach is the PATHS (Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies) curriculum, in which children learn to identify emotional expressions (using pictures, for example) and to think about the causes and consequences of different ways of expressing emotions (Domitrovich et al., 2007, 2010). In addition, the program provides children with opportunities to develop conscious strategies for self-control through verbal mediation (self-talk) and practicing ways to self-regulate. The PATHS approach is illustrated by the Control Signals Poster (CSP), which, like the Turtle Technique discussed in Chapter 1, is designed to remind children how to deal with troubling social situations:

The CSP is modeled after a traffic signal, with red, yellow, and green lights. The red light signals children to “Stop—Calm Down.” Here, youth are instructed that as challenging social situations occur, they should first “take a long deep breath,” calm down, and “say the problem and how they feel.” The yellow light signals children to “Slow Down—Think.” Here, youth make a plan by considering possible solutions and then selecting the best option. Finally, the green light signals children to “Go—Try My Plan.” Below the illustration of the stoplight are the words “Evaluate—How Did My Plan Work?” Students may then formulate and try new plans if necessary.

(Riggs et al., 2006, p. 94)

Programs like this one tend to be successful in fostering knowledge about emotions, self-regulation, prosocial behavior, and social competence—and sometimes in reducing social withdrawal and aggression as well (e.g., Bierman et al., 2010; Domitrovich et al., 2007; Izard et al., 2008; Riggs et al., 2006). Such improvements have been found especially for children with numerous problem behaviors and for children in disadvantaged schools (Bierman et al., 2010; Greenberg et al., 1995). The increases in social competence that often result as a consequence of participation in such an intervention would be expected to promote children’s social status, although this issue usually has not been specifically tested.

539

Stability of Sociometric Status

Do popular children always remain at the top of the social heap? Do rejected children sometimes become better liked? In other words, how stable is a child’s sociometric status in the peer group? The answer to this question depends in part on the particular time span and sociometric status that are in question.

Over relatively short periods such as weeks or a few months, children who are popular or rejected tend to remain so, whereas children who are neglected or controversial are likely to acquire a different status (Asher & Dodge, 1986; X. Chen, Rubin, & B. Li, 1995; Newcomb & Bukowski, 1984; S. Walker, 2009). Over longer periods, children’s sociometric status is more likely to change. In one study in which children were rated by their peers in 5th grade and again 2 years later, only those children who had initially been rated average maintained their status overall, whereas nearly two-thirds of those who had been rated popular, rejected, or controversial received a different rating later on (Newcomb & Bukowski, 1984). Over time, sociometric stability for rejected children is generally higher than for popular, neglected, or controversial children (Harrist et al., 1997; Parke et al., 1997; S. Walker, 2009) and may increase with the age of the child (Coie & Dodge, 1983; Rubin et al., 1998).

Cross-Cultural Similarities and Differences in Factors Related to Peer Status

Most of the research on behaviors associated with sociometric status has been conducted in the United States, but findings similar to those discussed here have been obtained in a wide array of cross-cultural research. In countries ranging from Canada, Italy, Australia, the Netherlands, and Greece to Indonesia, Hong Kong, Japan, and China, for example, socially rejected children tend to be aggressive and disruptive; and, in most countries, popular (i.e., well-liked) children tend to be described as prosocial and as having leadership skills (Attili, Vermigli, & Schneider, 1997; Chung-Hall & Chen, 2010; D. C. French, Setiono, & Eddy, 1999; Gooren et al., 2011; Hatzichristou & Hopf, 1996; Kawabata, Crick, & Hamaguchi., 2010; D. Schwartz et al., 2010; Tomada & Schneider, 1997; S. Walker, 2009; Y. Xu et al., 2004).

Similar cross-cultural parallels have been found with regard to withdrawal and rejection. Various studies done in Germany, Italy, and Hong Kong, for example, have shown that, as in the United States, withdrawal becomes linked with peer rejection in preschool or elementary school (Asendorpf, 1990; Attili et al., 1997; Casiglia, Lo Coco, & Zappulla, 1998; D. A. Nelson et al., 2010; D. Schwartz et al., 2010).

540

Research has also demonstrated that there are certain cultural and historical differences in the characteristics associated with children’s sociometric status. One notable example involving both types of differences is the status associated with shyness among Chinese children. In studies conducted in the 1990s, Chinese children who were shy, sensitive, and cautious, or inhibited in their behavior were—unlike their inhibited or shy Western counterparts—viewed by teachers as socially competent and as leaders, and they were liked by their peers ((X. Chen, Rubin, & B. Li, 1995; X. Chen, Rubin, & Z.-y. Li, 1995; X. Chen et al., 1999; X. Chen, Rubin, & Sun, 1992). A probable explanation for this difference is that Chinese culture traditionally values self-effacing, withdrawn behavior, and Chinese children are encouraged to behave accordingly (Ho, 1986).

In contrast, because Western cultures place great value on independence and self-assertion, withdrawn children in these cultures are likely to be viewed as weak, needy, and socially incompetent. However, Chen found that since the early 1990s, shy, reserved behavior in Chinese elementary school children has become increasingly associated with lower levels of peer acceptance, at least for urban children (X. Chen, Chang et al., 2005). Chen argues that the economic and political changes in China in the past decade have been accompanied by an increased valuing of assertive, less inhibited behavior. For children from rural areas who have had only limited exposure to the dramatic cultural changes in China in recent years, shyness is associated with high levels of both peer liking and disliking, albeit more to liking; thus, for groups somewhat less exposed to cultural changes, shyness is viewed with some ambivalence by peers (X. Chen, Wang, & Cao, 2011; X. Chen, Wang, & Wang, 2009). In addition, for the rural children, being unsociable—that is, uninterested in social interaction—is associated with peer rejection (X. Chen et al., 2009), whereas among North American children it often is not, at least for younger children. Thus, culture and changes in culture appear to affect children’s evaluations of what is desirable behavior.

Peer Status as a Predictor of Risk

Having an undesirable peer status has been associated with a variety of short-term and long-term risks and negative outcomes for children, including inferior academic performance, loneliness, delinquency, and poor adjustment.

Academic Performance

Research in a variety of regions, including North America, China, and Indonesia, indicates that rejected children, especially those who are aggressive, are more likely than their peers to have academic difficulties (X. Chen et al., 2011; Chung-Hall & Chen, 2010; D. C. French et al., 1999; Véronneau et al., 2010; Wentzel, 2009). In particular, they have higher rates of school absenteeism (DeRosier, Kupersmidt, & Patterson, 1994) and lower grade-point averages (Wentzel & Caldwell, 1997). Those who are aggressive are especially likely to be uninterested in school and to be viewed by peers and teachers as poor students (Hymel, Bowker, & Woody, 1993; Wentzel & Asher, 1995).

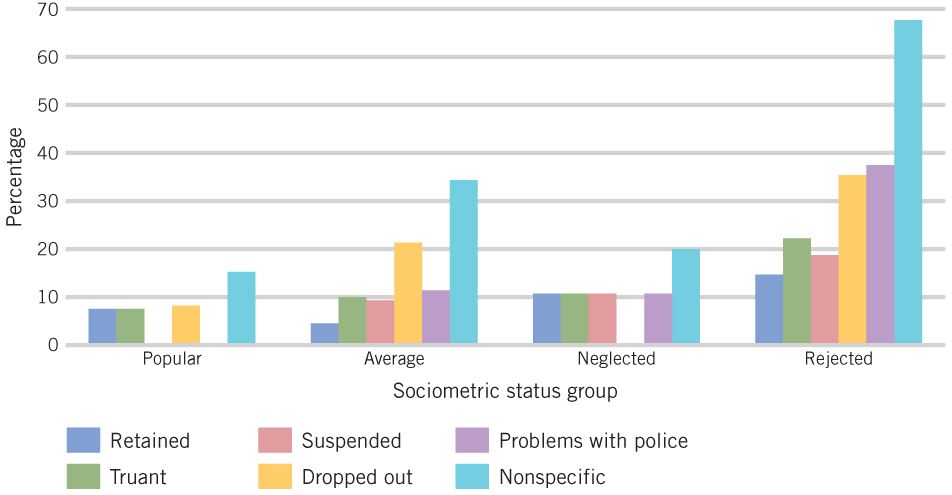

Longitudinal research, conducted mostly in the United States, indicates that students’ classroom participation is lower during periods in which they are rejected by peers than during periods when they are not, and that the tendency of rejected children to do relatively poorly in school worsens across time (Coie et al., 1992; Ladd, Herald-Brown, & Reiser, 2008; Ollendick et al., 1992). In one study that followed children from 5th grade through the high school years, rejected children were much more likely than other children, especially popular children, to be required to repeat a grade or to be suspended from school, to be truants, or to drop out (Kupersmidt & Coie, 1990) (Figure 13.2). They were also more likely to have difficulties with the law—in many cases, no doubt, deepening their academic difficulties. All told, approximately 25% to 30% of rejected children drop out of school, compared with approximately 8% or less of other children (Parker & Asher, 1987; Rubin et al., 1998).

541

Problems with Adjustment

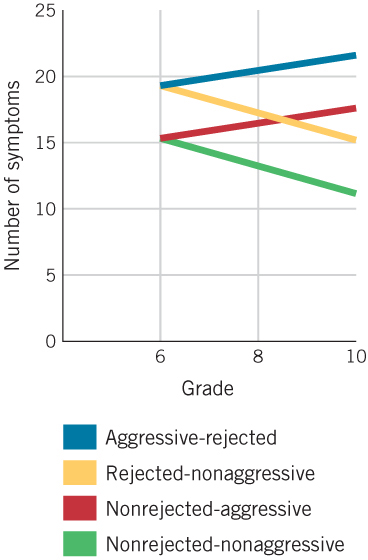

Children who are rejected in the elementary school years—especially aggressive-rejected boys—are at risk for increases in externalizing symptoms such as aggression, delinquency, hyperactivity and attention-deficit disorders, conduct disorder, and substance abuse (Criss et al., 2009; Lansford et al., 2010; Ollendick et al., 1992; Sturaro et al., 2011; Vitaro et al., 2007). In one longitudinal study that followed more than 1000 U.S. children from 3rd to 10th grade (Coie et al., 1995), boys and girls who were assessed as rejected in 3rd grade were, according to parent reports, higher than their peers in externalizing symptoms 3 years and 7 years later. In addition, aggressive boys (both rejected and nonrejected) increased in parent-reported externalizing symptoms between grades 6 and 10, whereas other boys did not; and by 10th grade, aggressive-rejected boys themselves reported an average of more than twice the number of symptoms reported by all other boys (Figure 13.3).

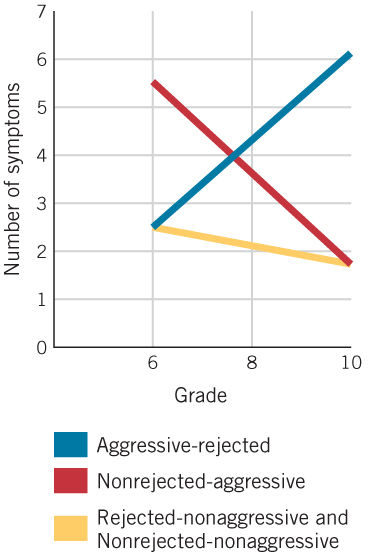

Other research provides evidence that peer rejection may also be associated with internalizing problems such as loneliness, depression, withdrawn behavior, and obsessive-compulsive behavior (Gooren et al., 2011; Prinstein et al., 2009), even 10 to 40 years later (Modin, Östberg, & Almquist, 2011). In the longitudinal study of more than 1000 children mentioned above, girls and boys who were rejected in 3rd grade were, as reported by parents, higher than their peers in internalizing symptoms by 6th grade and 10th grade. Moreover, aggressive-rejected boys themselves reported a marked increase in internalizing symptoms from 6th to 10th grade, whereas all other boys reported a drop in these symptoms (Figure 13.4). Aggressive-rejected girls were viewed by parents as most prone to internalizing problems by grade 10. Thus, both boys and girls who were assessed as rejected in 3rd grade—especially if they also were aggressive—were at risk for developing internalizing problems years later (Coie et al., 1995).

542

Also at risk for internalizing problems in Western cultures are children who are very withdrawn but nonaggressive with their peers. As you have seen, although these children tend to become rejected by the middle to late elementary school years, they are generally not at risk for the behavioral problems that aggressive-rejected children often experience. However, a consistent pattern of social withdrawal, social anxiety, and wariness with familiar people, including peers, is associated with symptoms such as depression, low self-worth, and loneliness in childhood and into early adulthood (Hoza et al., 1995; S. J. Katz et al., 2011; Rubin et al., 2009).

Children who are socially withdrawn amid familiar peers may differ in important ways from their peers even in adulthood. In a longitudinal study of American children born in the late 1920s, boys who were rated by their teachers as reserved and unsociable were less likely to have been married and to have children than were less reserved boys. They also tended to begin their careers at later ages, had less success in their careers, and were less stable in their jobs. Reserved men who were late in establishing stable careers had twice the rate of divorce and marital separation by midlife as did their less reserved peers.

In contrast, reserved girls were more likely than their less reserved peers to have a conventional lifestyle of marriage, parenthood, and homemaking rather than working outside the home. Thus, a reserved style of interaction at school during childhood was associated with more negative outcomes for men than for women, perhaps because a reserved style was more compatible with the feminine homemaker role of the times than with the demands of achieving outside the home (Caspi, Elder, & Bem, 1988).

victimized (peer status) with respect to peer relationships, this term refers to children who are targets of their peers’ aggression and demeaning behavior

A final group of rejected children who may be especially at risk for loneliness and other internalizing problems is victimized children, who are targets of their peers’ aggression and demeaning behavior. Although the sequence of events is not entirely clear, it appears that children in this group are more likely to be rejected first and then victimized rather than the reverse (Hanish & Guerra, 2000a; D. Schwartz et al., 1999).

Victimized children tend to be aggressive, as well as withdrawn and anxious (Barker et al., 2008; D. Schwartz et al., 1998; J. Snyder, Brooker et al., 2003; Tom et al., 2010), and the relation between victimization and aggression appears to be bidirectional (Reijntjes et al., 2011; van Lier et al., 2012). Aggression sometimes appears to elicit victimization by peers (Barker et al., 2008; Kawabata et al., 2010).

Other factors might also contribute to victimization. For example, immigrant children are more likely to be victimized than are peers who are part of the majority group, likely because they are seen as different (Strohmeier, Kärnä, & Salmivalli, 2011; von Grünigen et al., 2010). In addition, hereditary factors associated with aggression appear to predict peer victimization, suggesting that temperamental or other personal characteristics may increase the likelihood of children becoming both aggressive and victimized (Brendgen et al., 2011). For example, low self-regulation is related to both aggression and peer victimization (N. Eisenberg, Sallquist et al., 2009; Iyer et al., 2010) and may contribute to both.

543

Unfortunately, peer victimization is not an uncommon event and can begin quite early. In one study in the United States, approximately one-fifth of kindergartners were repeatedly victimized by peers (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). Over time, victimization by peers likely increases children’s aggression, withdrawal, depression, and loneliness (Nylund et al., 2007; D. Schwartz et al., 1998), leading to hanging out with peers who are engaged in deviant behaviors (Rudolph et al., 2013), as well as problems at school and absenteeism (Juvonen, Nishina, & Graham, 2000; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996; Nakamoto & Schwartz, 2010). Although the rate of victimization generally appears to be lower among older children (Olweus, 1994), peer victimization is a serious problem that warrants concern, especially since the same children tend to be victimized again and again (Hanish & Guerra, 2000b).

Paths to Risk

Clearly, children who are rejected by peers are at risk for academic and adjustment problems. The key question is whether peer rejection actually causes problems at school and in adjustment, or whether children’s maladaptive behavior (e.g., aggression) leads to both peer rejection and problems in adjustment (Parker et al., 1995; L. J. Woodward & Fergusson, 1999). Although conclusive evidence is not yet available, findings suggest that peer status and the quality of children’s social behavior have partially independent effects on subsequent adjustment (Coie et al., 1992; DeRosier et al., 1994). Moreover, early maladjustment, such as internalizing problems, may contribute to both future maladaptive behavior (e.g., aggression) and peer victimization, which in turn may lead to more internalizing problems over time (Leadbeater & Hoglund, 2009). Thus, it is likely that there are complex bidirectional relations among children’s adjustment, social competencies, and peer acceptance (Boivin et al., 2010; Fergusson, Woodward, & Horwood, 1999; Lansford et al., 2010; Obradovi´c & Hipwell, 2010).

Once children are rejected by peers, they may be denied opportunities for positive peer interactions and thus for learning social skills. Moreover, cut off from desirable peers, they may be forced to associate with other rejected children, and rejected children may teach one another, and mutually reinforce, deviant norms and behaviors. The lack of social support from peers also may increase rejected children’s vulnerability to the effects of stressful life experiences (e.g., poverty, parental conflict, divorce), negatively influencing their social behavior even further, which in turn affects both their peer status and adjustment.

review:

Children’s sociometric status is assessed by peers’ reports of their liking and disliking of one another. On the basis of such reports, children typically have been classified as popular, rejected, average, neglected, or controversial.

Well-liked, popular children tend to be attractive, socially skilled, prosocial, well regulated, and low in aggression that is driven by anger, vengefulness, or satisfaction in hurting others. However, some children who are viewed as popular by their peers are aggressive and not especially well-liked. Some rejected children tend to be relatively aggressive, disruptive, and low in social skills; they also tend to make hostile attributions about others’ intentions and have trouble dealing with difficult social situations in a constructive manner. Withdrawn children who are aggressive and hostile as well are also rejected by peers by kindergarten age. In contrast, most children who are withdrawn from their peers but are not hostile and aggressive are at somewhat less risk, although they sometimes become rejected later in elementary school.

544

Neglected children interact less frequently with peers than do children who are average in sociometric status, and they display relatively few behaviors that differ greatly from those of many other children. Controversial children display characteristics of both popular and rejected children and tend to be very socially active. Children who are neglected or controversial, unlike rejected children, are particularly likely to change their status, even over short periods.

Rejection by peers in childhood—especially rejection due to aggression—predicts relatively high levels of subsequent academic problems and externalizing behaviors. Rejected children also tend to become more withdrawn and are prone to loneliness and depression. It is likely that children’s maladaptive behavior as well as their low status with peers contribute to these negative developmental outcomes.