Moral Judgment

The morality of a given action cannot be determined at face value. Consider a girl who steals food to feed her starving sister. Stealing is usually regarded as an immoral behavior, but obviously the morality of this girl’s behavior is not so clear. Or consider an adolescent male who offers to help fix a peer’s bike but does so because he wants to borrow it later, or perhaps wants to find out if the bike is worth stealing. Although this adolescent’s behavior may appear altruistic on the surface, it is morally ambiguous, at best, in the first instance and clearly immoral in the second. These examples illustrate that the morality of a behavior is based partly on the cognitions—including conscious intentions and goals—that underlie the behavior.

Indeed, some psychologists (as well as philosophers and educators) believe that the reasoning behind a given behavior is critical for determining whether that behavior is moral or immoral, and they maintain that changes in moral reasoning form the basis of moral development. As a consequence, much of the research on children’s moral development has focused on how children think when they try to resolve moral conflicts and how their reasoning about moral issues changes with age. The most important contributors to the current understanding of the development of children’s moral reasoning are Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg, both of whom took a cognitive developmental approach to studying the development of morality.

Piaget’s Theory of Moral Judgment

The foundation of cognitive theories about the origin of morality is Piaget’s book The Moral Judgment of the Child (1932/1965). In it, Piaget describes how children’s moral reasoning changes from a rigid acceptance of the dictates and rules of authorities to an appreciation that moral rules are a product of social interaction and are therefore modifiable. Piaget believed that interactions with peers, more than adult influence, account for advances in children’s moral reasoning.

556

Piaget initially studied children’s moral reasoning by observing children playing games, such as marbles, in which they often deal with issues related to rules and fairness. In addition, Piaget interviewed children to examine their thinking about issues such as transgressions of rules, the role of intentionality in morality, fairness of punishment, and justness when distributing goods among people. In these open-ended interviews, he typically presented children with pairs of short vignettes such as the following:

A little boy who is called John is in his room. He is called to dinner. He goes into the dining room. But behind the door there was a chair, and on the chair there was a tray with fifteen cups on it. John couldn’t have known that there was all this behind the door. He goes in, the door knocks against the tray, bang go the fifteen cups, and they all get broken!

Once there was a little boy whose name was Henry. One day when his mother was out he tried to get some jam out of the cupboard. He climbed up on to a chair and stretched out his arm. But the jam was too high up and he couldn’t reach it and have any. But while he was trying to get it he knocked over a cup. The cup fell down and broke.

(Piaget, 1932/1965, p. 122)

After children heard these stories, they were asked which boy was naughtier, and why. Children younger than 6 years typically said that the child who broke 15 cups was naughtier. In contrast, older children said that the child who was trying to sneak jam was naughtier, even though he broke only one cup. Partly on the basis of children’s responses to such vignettes, Piaget concluded that there are two stages of development in children’s moral reasoning, as well as a transitional period between the stages.

The Stage of the Morality of Constraint

The first stage of moral reasoning, referred to as the morality of constraint, is most characteristic of children who have not achieved Piaget’s stage of concrete operations—that is, children younger than 7 years (see Chapter 4). Children in this stage regard rules and duties to others as unchangeable “givens.” In their view, justice is whatever authorities (adults, rules, or laws) say is right, and authorities’ punishments for noncompliance are always justified. Acts that are not consistent with rules and authorities’ dictates are “bad”; acts that are consistent with them are “good.” It is in this stage that children believe that what determines whether an action is good or bad are the consequences of the action, not the motives or intentions behind it.

Piaget suggested that young children’s belief that rules are unchangeable is due to two factors, one social and one cognitive. First, Piaget argued that parental control of children is coercive and unilateral, leading to children’s unquestioning respect for rules set by adults. Second, children’s cognitive immaturity causes them to believe that rules are “real” things, like chairs or gravity, that exist outside people and are not the product of the human mind.

The Transitional Period

According to Piaget, the period from about age 7 or 8 to age 10 represents a transition from the morality of constraint to the next stage. During this transitional period, children typically have more interactions with peers than previously, and these interactions are more egalitarian, with more give-and-take, than are their interactions with adults. In games with peers, children learn that rules can be constructed and changed by the group. They also increasingly learn to take one another’s perspective and to cooperate. As a consequence, children start to value fairness and equality and begin to become more autonomous in their thinking about moral issues. Piaget viewed children as taking an active role in this transition, using information from their social interactions to figure out how moral decisions are made and how rules are constructed.

557

The Stage of Autonomous Morality

By about age 11 or 12, Piaget’s second stage of moral reasoning emerges. In this stage, referred to as the stage of autonomous morality (also called moral relativism), children no longer accept blind obedience to authority as the basis of moral decisions. They fully understand that rules are the product of social agreement and can be changed if the majority of a group agrees to do so. In addition, they consider fairness and equality among people as important factors to consider when constructing rules. Children at this stage believe that punishments should “fit the crime” and that punishment delivered by adults is not necessarily fair. They also consider individuals’ motives and intentions when evaluating their behavior; thus, they view breaking one cup while trying to sneak jam as worse than accidentally breaking 15 cups.

According to Piaget, all normal children progress from the morality of constraint to autonomous moral reasoning. Individual differences in the rate of their progress are due to numerous factors, including differences in children’s cognitive maturity, in their opportunities for interactions with peers and for reciprocal role taking, and in how authoritarian and punitive their parents are.

Evaluation of Piaget’s Theory

Piaget’s general vision of moral development has received some support from empirical research. Studies of children from many countries and various racial or ethnic groups have shown that with age, boys and girls increasingly take motives and intentions into account when judging the morality of actions (N. E. Berg & Mussen, 1975; Lickona, 1976). In addition, parental punitiveness, which would be expected to reinforce a morality of constraints, has been associated with less mature moral reasoning and moral behavior (M. L. Hoffman, 1983). Finally, consistent with Piaget’s belief that cognitive development plays a role in the development of moral judgment, children’s performance on tests of perspective-taking skills, Piagetian logical tasks, and IQ tests have all been associated with their level of moral judgment (N. E. Berg & Mussen, 1975; Lickona, 1976).

Some aspects of Piaget’s theory, however, have been soundly faulted. For example, there is little evidence that peer interaction per se stimulates moral development (Lickona, 1976). Rather, it seems likely that the quality of peer interactions—for example, whether or not they involve cooperative interactions—is more important than mere quantity of interaction with peers. Piaget also underestimated young children’s ability to appreciate the role of intentionality in morality (Nobes, Panagiotaki, & Pawson 2009). When Piagetian moral vignettes are presented in ways that make the individuals’ intentions more obvious—such as by using videotaped dramas—preschoolers and early elementary school children are more likely to recognize individuals with bad intentions (Chandler et al., 1973; Grueneich, 1982; Yuill & Perner, 1988). It is probable that in Piaget’s research, young children focused primarily on the consequences of the individuals’ actions because consequences (e.g., John’s breaking the 15 cups) were very salient in his stories.

558

In addition, many 4- and 5-year-olds do not think that a person caused a negative outcome “on purpose” if they have been explicitly told that the person had no foreknowledge of the consequences of his or her action or believed that the outcome of the action would be positive rather than negative (Pellizzoni, Siegal, & Surian, 2009). Moreover, even younger children seem to use knowledge of intentionality to evaluate others’ behavior. In one study, 3-year-olds who saw an adult intend (but fail) to hurt another adult were less likely to help that person than they were if the person’s behavior toward the other adult was neutral (intended to neither help nor hurt the other). In contrast, they helped an adult who accidently caused harm as much as they helped an adult whose behavior was neutral (Vaish, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2010). Equally impressive, 21-month-olds in another study were more likely to help an adult who had tried (but failed) to assist them in retrieving a toy than an adult who had been unwilling to assist them. They were also more likely to help an adult who had tried (but failed) to assist them than an adult whose intentions had not been clear (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2010). Finally, as you will see later in the chapter, it is clear that young children do not believe that some actions, such as hurting others, are right even when adults say they are.

Whatever its shortcomings, Piaget’s theory provided the basis for subsequent research on the development of moral judgment. The most notable example is the more complexly differentiated theory of moral development formulated by Kohlberg.

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Judgment

Heavily influenced by the ideas of Piaget, Kohlberg (1976; Colby & Kohlberg, 1987a) was primarily interested in the sequences through which children’s moral reasoning develops. On the basis of a 20-year longitudinal study in which he first assessed boys’ moral reasoning at ages 10, 13, and 16, Kohlberg proposed that moral development proceeds through a specific series of stages that are discontinuous and hierarchical. That is, each new stage reflects a qualitatively different, more adequate way of thinking than the one before it.

Kohlberg assessed moral judgment by presenting children with hypothetical moral dilemmas and then questioning them about the issues these dilemmas involved. The most famous of these dilemmas concerns a man named Heinz, whose wife was dying from a special kind of cancer:

There was one drug that the doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging 10 times what it cost him to make. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money and tried every legal means, but he could only get together about $2,000, which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist his wife was dying, and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said, “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So having tried every legal means, Heinz gets desperate and considers breaking into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife.

(Colby & Kohlberg 1987b, p. 1)

Video: Moral Development: Kolhberg Heinz Moral Dilemma

After relating this dilemma to children, Kohlberg asked them questions such as: Should Heinz steal the drug? Would it be wrong or right if he did? Why? Is it a husband’s duty to steal the drug for his wife if he can get it no other way? For Kohlberg, the reasoning behind choices of what to do in the dilemma, rather than the choices themselves, is what reflects the quality of their moral reasoning. For example, the response that “Heinz should steal the drug because he probably won’t get caught and put in jail” was considered less advanced than “Heinz should steal the drug because he wants his wife to feel better and to live.”

559

Kohlberg’s Stages

On the basis of the reasoning underlying children’s responses, Kohlberg proposed three levels of moral judgment—preconventional, conventional, and postconventional (or principled). Preconventional moral reasoning is self-centered: it focuses on getting rewards and avoiding punishment. Conventional moral reasoning is centered on social relationships: it focuses on compliance with social duties and laws. Postconventional moral reasoning is centered on ideals: it focuses on moral principles. Each of these three levels involves two stages of moral judgment (see Table 14.1). However, so few people ever attained the highest stage (Stage 6—Universal Ethical Principles) of the postconventional level that Kohlberg (1978) eventually stopped scoring it as a separate stage, and many theorists consider it an elaboration of Stage 5 (Lapsley, 2006).

560

Kohlberg argued that people in all parts of the world move through his stages in the same order, although they differ in how many stages they attain. As in Piaget’s theory, age-related advances in cognitive skills, especially perspective taking, are believed to underlie the development of higher-level moral judgment. Consistent with Kohlberg’s theory, people who have higher-level cognitive and perspective-taking skills and who are better educated exhibit higher-level moral judgment (Colby et al., 1983; Mason & Gibbs, 1993; Rest, 1983).

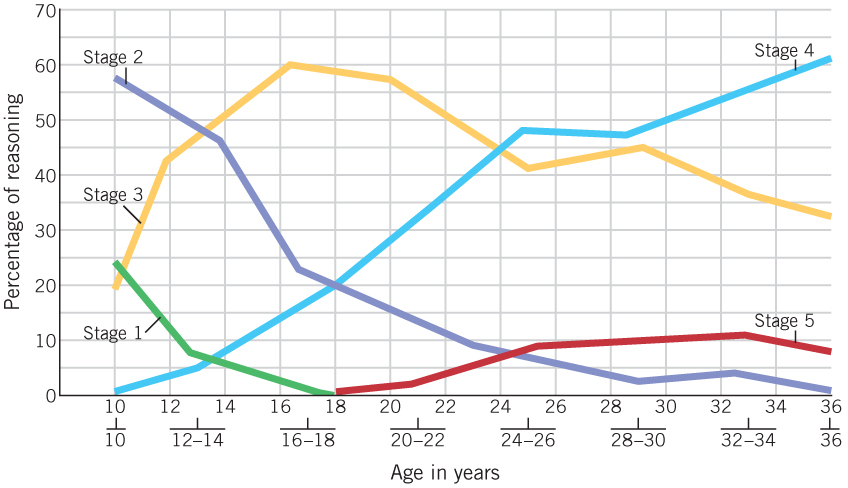

In their initial longitudinal study, Kohlberg and his colleagues (Colby et al., 1983) followed 58 boys into adulthood and found that moral judgment changed systematically with age (see Figure 14.1). When the boys were 10 years old, they used primarily Stage 1 reasoning (blind obedience to authority) and Stage 2 reasoning (self-interest). Thereafter, reasoning in these stages dropped off markedly. For most adolescents aged 14 and older, Stage 3 reasoning (being “good” to earn approval or maintain relationships) was the primary mode of reasoning, although some adolescents occasionally used Stage 4 reasoning (fulfilling duties and upholding laws to maintain social order). Only a small number of participants, even by age 36, ever achieved Stage 5 (upholding the best interests of the group while recognizing life and liberty as universal values).

Video: Interview with Lawrence Walker

Critique of Kohlberg’s Theory

Kohlberg’s work is important because it demonstrated that children’s moral judgment changes in relatively systematic ways with age. In addition, because individuals’ levels of moral judgment have been related to their moral behavior, especially for people reasoning at higher levels (e.g., Kutnick, 1985; B. Underwood & Moore, 1982), Kohlberg’s work has been useful in understanding how cognitive processes contribute to moral behavior.

Kohlberg’s theory and findings have also produced controversy and criticism. One criticism is that Kohlberg did not sufficiently differentiate between truly moral issues and issues of social convention (Nucci & Gingo, 2011) (we examine this differentiation on pages 563–565). Another criticism pertains to cultural differences. Although children in many non-Western, nonindustrialized cultures start out reasoning much the way Western children do in Kohlberg’s scoring system, their moral judgment within this system generally does not advance as far as that of their Western peers (e.g., Nisan & Kohlberg, 1982; Snarey, 1985). This finding has led to the objection that Kohlberg’s stories and scoring system reflect an intellectualized conception of morality that is biased by Western values (E. L. Simpson, 1974). In many non-Western societies, in which the goal of preserving group harmony is of critical importance and most conflicts of interest are worked out through face-to-face contact, issues of individual rights and civil liberties may not be viewed as especially relevant. Moreover, in some societies, obedience to authorities, elders, and religious dictates are valued more than principles of freedom and individual rights.

561

Another criticism has to do with Kohlberg’s argument that change in moral development is discontinuous. Kohlberg asserted that because each stage is more advanced than the previous one, once an individual attains a new stage, he or she seldom reasons at a lower stage. However, research has shown that children and adults alike often reason at different levels on different occasions—or even on the same occasion (Rest, 1979). As a consequence, it is not clear that the development of moral reasoning is qualitatively discontinuous. Rather, children and adolescents may gradually acquire the cognitive skills to use increasingly higher stages of moral reasoning but also may use lower stages when it is consistent with their goals, motives, or beliefs in a particular situation. For example, even an adolescent who is capable of using Stage 4 reasoning may well use Stage 2 reasoning to justify a decision to break the law for personal gain.

A hotly debated issue regarding Kohlberg’s theory is whether there are gender differences in moral judgment. As noted previously, Kohlberg developed his conception of moral-reasoning stages on the basis of interviews with a sample of boys. Carol Gilligan (1982) argued that Kohlberg’s classification of moral judgment is biased against females because it does not adequately recognize differences in the way males and females reason morally. Gilligan suggested that because of the way they are socialized, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring, responsibility for others, and avoidance of exploiting or hurting others (Gilligan & Attanucci, 1988). This difference in moral orientation, according to Gilligan, causes males to score higher on Kohlberg’s dilemmas than females do.

Contrary to Gilligan’s theory, there is little evidence that boys and girls, or men and women, score differently on Kohlberg’s stages of moral judgment (Turiel, 1998; L. J. Walker, 1984, 1991). However, consistent with Gilligan’s arguments, during adolescence and adulthood, females focus somewhat more on issues of caring about other people in their moral judgment (Garmon et al., 1996; Jaffee & Hyde, 2000). Differences in males’ and females’ moral reasoning seem to be most evident when individuals report on moral dilemmas in their own lives (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000). Thus, Gilligan’s work has been very important in broadening the focus of research on moral reasoning and in demonstrating that males and females differ somewhat in the issues they focus on when confronting moral issues.

Although Kohlberg’s stages probably are not as invariant in sequence nor as universal as he claimed, they do describe changes in children’s moral reasoning that are observed in many Western societies. These changes are important because people with higher-level moral reasoning are more likely to behave in a moral manner (Kohlberg & Candee, 1984; Matsuba & Walker, 2004) and to assist others (Blasi, 1980), and they are less likely to engage in delinquent activities (Stams et al., 2006). Thus, understanding developmental changes in moral judgment provides insight into why, as children grow older, they tend to engage in more prosocial behavior.

562

Prosocial Moral Judgment

When children respond to Kohlberg’s dilemmas, they are choosing between two acts that are wrong—for example, stealing or allowing someone to die. However, there are other types of moral dilemmas children encounter in which the choice is between personal advantage versus fairness to, or the welfare of, others (Damon, 1977; N. Eisenberg, 1986; Skoe, 1998).

prosocial behavior voluntary behavior intended to benefit another, such as helping, sharing, and comforting of others

To determine how children resolve these dilemmas, researchers present children with stories in which the characters must choose between helping someone or meeting their own needs. These dilemmas are called prosocial moral dilemmas and concern prosocial behavior—that is, voluntary behavior intended to benefit another, such as helping, sharing, and comforting of others. The following story illustrates the type of dilemma used with children 4 years or older (with slight modifications for the latter group):

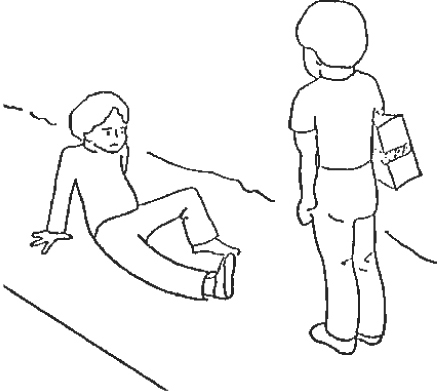

One day a boy named Eric was going to a friend’s birthday party. On his way he saw a boy who had fallen down and hurt his leg [see Figure 14.2]. The boy asked Eric to go to his house and get his parents so the parents could come and take him to a doctor. But if Eric did run and get the child’s parents, he would be late to the birthday party and miss the ice cream, cake, and all the games.

What should Eric do? Why?

(Eisenberg-Berg & Hand, 1979, p. 358)

On these tests, children and adolescents use five levels of prosocial moral reasoning, delineated by Eisenberg (1986), that resemble Kohlberg’s stages (see Table 14.2). Preschool children express primarily hedonistic reasoning (Level 1) in which their own needs are central. They typically indicate that Eric should go to the party because he wants to. However, preschoolers also often mention other people’s physical needs, which suggests that some preschoolers are concerned about other people’s welfare (Level 2). (For example, they may indicate that Eric should help because the other boy is bleeding or hurt.) Such recognition of others’ needs increases in the elementary school years. In addition, in elementary school, children increasingly express concern about social approval and acting in a manner that is considered “good” by other people and society (e.g., they indicate that Eric should help “to be good”; Level 3).

In late childhood and adolescence, children’s judgments begin to be based, in varying degrees, on explicit perspective taking (Level 4a—e.g., “Eric should think about how he would feel in that situation”) and morally relevant affect such as sympathy, guilt, and positive feelings due to the real or imagined consequences of performing beneficial actions (e.g., “Eric would feel bad if he didn’t help and the boy was in pain”). The judgments of a minority of older adolescents reflect internalized values and affect (Levels 4b and 5) related to not living up to those values (e.g., self-censure).

In general, this pattern of changes in prosocial moral reasoning has been found for children in Brazil, Germany, Israel, and Japan (Carlo et al., 1996; N. Eisenberg et al., 1985; I. Fuchs et al., 1986; Munekata & Ninomiya, 1985). Nevertheless, children from different cultures do vary somewhat in their prosocial moral reasoning. For example, stereotypic and internalized reasoning were not clearly different factors for Brazilian older adolescents and adults, whereas the two types of reasoning were somewhat more different for similar groups in the United States (Carlo et al., 2008). Moreover, older children (and adults) in some traditional societies in Papua New Guinea exhibit higher-level reasoning less often than do people of the same age in Western cultures. However, the types of reasoning they frequently use—reasoning that pertains to others’ needs and the relationship between people—are consistent with the values of a culture in which people must cooperate with one another in face-to-face interactions in order to survive (Tietjen, 1986). In nearly all cultures, reasoning that reflects the needs of others and global concepts of good and bad behavior (Kohlberg’s Stage 3 and Eisenberg’s Level 3) emerges at somewhat younger ages on prosocial dilemmas than on Kohlberg’s moral dilemmas.

563

With age, children’s prosocial moral judgment, like their reasoning on Kohlberg’s moral dilemmas, becomes more abstract and based more on internalized principles and values (N. Eisenberg, 1986; N. Eisenberg et al., 1995). Paralleling the case with moral reasoning on Kohlberg’s measure, in numerous cultures those children, adolescents, and young adults who use higher-level prosocial moral reasoning tend to be more sympathetic and prosocial in their behavior than do peers who use lower-level prosocial moral judgment (Carlo, Knight et al., 2010; N. Eisenberg, 1986; Janssens & Dekovic, 1997; Kumru et al., 2012).

Domains of Social Judgment

moral judgments decisions that pertain to issues of right and wrong, fairness, and justice

In everyday life, children make decisions about many kinds of actions, including whether to follow rules and laws or break them, whether to fight or walk away from conflict, whether to dress formally or informally, whether to study or goof off after school, and so on. Some of these decisions involve moral judgments; others involve social conventional judgments; and still others involve personal judgments (Nucci, 1981; Turiel, 2006).

social conventional judgments decisions that pertain to customs or regulations intended to secure social coordination and social organization

564

Moral judgments pertain to issues of right and wrong, fairness, and justice. Social conventional judgments pertain to customs or regulations intended to ensure social coordination and social organization, such as choices about modes of dress, table manners, and forms of greeting (e.g., using “Sir” when addressing a male teacher). Personal judgments pertain to actions in which individual preferences are the main consideration. For example, within Western culture, the choice of friends or recreational activities usually is considered a personal choice (Nucci & Weber, 1995). These distinctions are important because whether children perceive particular judgments as moral, social conventional, or personal affects the importance they accord them.

Children’s Use of Social Conventional Judgment

personal judgments decisions that refer to actions in which individual preferences are the main consideration

In many cultures, children begin to differentiate between moral and social conventional issues at an early age (J. G. Miller & Bersoff, 1992; Nucci, Camino, & Sapiro, 1996; Smetana et al., 2012; Tisak, 1995). By age 3, they generally believe that moral violations (e.g., stealing another child’s possession or hitting another child) are more wrong than social conventional violations (e.g., not saying “please” when asking for something or wearing other-gender clothing). By age 4, they believe that moral transgressions, but not social conventional transgressions, are wrong even if an adult does not know about them and even if adult authorities have not said they are wrong (Smetana & Braeges, 1990). This distinction is reflected in the following excerpt from an interview with a 5-year-old boy:

Interviewer: This is a story about Park School. In Park School the children are allowed to hit and push others if they want. It’s okay to hit and push others. Do you think it is all right for Park School to say children can hit and push others if they want to?

Boy: No. It is not okay.

Interviewer: Why not?

Boy: Because that is like making other people unhappy. You can hurt them that way. It hurts other people, hurting is not good.

This boy is firm in his belief that hurting others is wrong, even if adults say it is acceptable. Children tend to justify their condemnation of moral violations by referring to violations of fairness and harm to others’ welfare (Turiel, 2008). Compare that reasoning with the boy’s response to a question about the acceptability of a school policy that allows children to take off their clothes in hot weather.

Interviewer: I know another school in a different city.…Grove School…At Grove School the children are allowed to take their clothes off if they want to. Is it okay or not okay for Grove School to say children can take their clothes off if they want to?

Boy: Yes. Because this is the rule.

Interviewer: Why can they have that rule?

Boy: If that’s what the boss wants to do, he can do that.…He is in charge of the school.

(Turiel, 1987, p. 101)

With regard to both moral and social conventional issues in the family, children and, to a lesser degree, adolescents, believe that parents have authority (Smetana, 1988; Yau, Smetana, & Metzger, 2009), unless the parent gives commands that violate moral and conventional principles (Yamada, 2009). With respect to matters of personal judgment, however, even preschoolers tend to believe that they themselves should have control, and older children and adolescents are quite firm in their belief that they should control choices in the personal domain (e.g., their appearance, how they spend their money, and their choice of friends) at home and at school (Lagattuta et al., 2010; Nucci & Gingo, 2011). At the same time, parents usually feel that they should have some authority over their children’s personal choices, even into adolescence, so parents and teenagers frequently do battle in this domain—battles that parents often lose (Lins-Dyer & Nucci, 2007; Smetana, 1988; Smetana & Asquith, 1994).

565

Cultural and Socioeconomic Differences

People in different cultures sometimes vary in whether they view decisions as moral, social conventional, or personal (Shweder et al., 1987). Take the question of one’s obligation to attend to the minor needs of parents and the moderate needs of friends or strangers. Hindu Indians believe that they have a clear moral obligation to attend to these needs (J. G. Miller, Bersoff, & Harwood, 1990). In contrast, Americans appear to consider it a matter of personal choice or a combination of moral and personal choice. This difference in perceptions may be due to the strong cultural emphasis on individual rights in the United States and the emphasis on duties to others in India (Killen & Turiel, 1998; J. G. Miller & Bersoff, 1995).

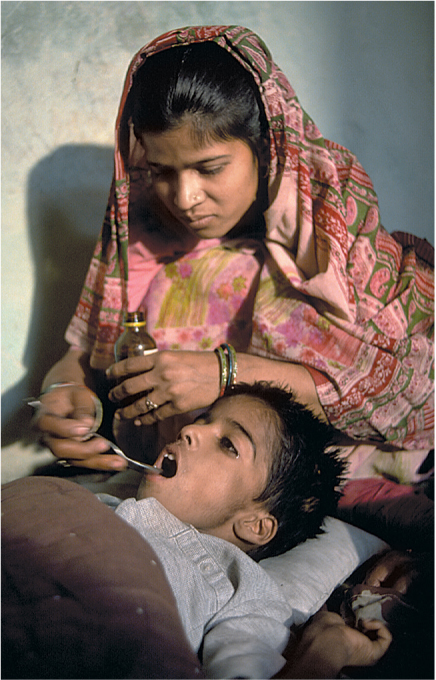

Cultural differences with regard to which events are considered moral, social conventional, or personal sometimes arise from religious beliefs (Turiel, 2006; Wainryb & Turiel, 1995). For example, Hindus in India believe that if a widow eats fish, she has committed an immoral act. In Hindu society, fish is viewed as a “hot” food, and eating “hot” food is believed to stimulate the sexual appetite. Consequently, traditional Hindu adults and children assume that a widow who eats fish will behave immorally and offend her husband’s spirit. Underlying this belief is the obligation that Hinduism places on a widow to seek salvation and be reunited with the soul of her husband rather than initiating another relationship (Shweder et al., 1987). Of course, for most other people in the world, a widow’s eating fish would be considered a matter of personal choice. Thus, beliefs regarding the significance and consequences of various actions in different cultures can influence the designation of behaviors as moral, social conventional, or personal.

Even within a given culture, different religious beliefs may affect what is considered a moral or a social-conventional issue. In Finland, for example, conservative religious adolescents are less likely to make a distinction between the moral and social-conventional domain than are nonreligious youths. For the religious youths, the most crucial deciding factor for nonmoral (conventional) issues is God’s word as written in the Bible (i.e., whether or not the Bible says a particular social convention is wrong; Vainio, 2011).

Socioeconomic class can also influence the way children make such designations. Research in the United States and Brazil indicates that children of lower-income families are somewhat less likely than middle-class children to differentiate sharply between moral and social conventional actions and, prior to adolescence, are also less likely to view personal issues as a matter of choice. These differences may be due to the tendency of individuals of low socioeconomic status both to place a greater emphasis on submission to authority and to allow children less autonomy (Nucci, 1997). This social-class difference in children’s views may evaporate as youths approach adolescence, although Brazilian mothers of lower-income youths still claim more control over personal issues than do mothers of middle-income youths (Lins-Dyer & Nucci, 2007).

566

review:

How children think about moral issues provides one basis for their moral or immoral behavior. Piaget delineated two moral stages—morality of constraint and autonomous morality—separated by a transitional stage. In the first stage, children regard rules as fixed and tend to weigh consequences more than intentions in evaluating actions. According to Piaget, a combination of cognitive growth and egalitarian, cooperative interactions with peers brings children to the autonomous stage, in which they recognize that rules can be changed by group consent and judge the morality of actions on the basis of intentions more than consequences. Aspects of Piaget’s theory have not held up well to criticism—for example, children use intentions to evaluate behavior at a younger age than Piaget believed they could—but his theory provided the foundation for Kohlberg’s work on stages of moral reasoning.

Kohlberg outlined three levels of moral judgment—preconventional, conventional, and postconventional—each initially containing two stages (Stage 6 was subsequently dropped). He hypothesized that his sequence of stages reflected age-related discontinuous changes in moral reasoning and that children everywhere go through the same stage progression (although they may stop development at different points). Several aspects of Kohlberg’s theory are controversial, including whether children’s moral reasoning moves through discontinuous stages of development; whether the theory is valid for all cultures; and whether there are gender differences in moral judgment. Research on other types of moral judgment, such as prosocial moral judgment, suggests that children’s concerns about the needs of others emerge at a younger age than Kohlberg’s work indicates. However, with age, prosocial moral reasoning, like Kohlberg’s justice-oriented moral reasoning, becomes more abstract and based on internalized principles.

There are important differences among the moral, social conventional, and personal domains of behavior and judgment—differences that even children recognize. For example, young children believe that moral transgressions, but not social conventional or personal violations, are wrong regardless of whether adults say they are unacceptable. There are some cultural differences in whether a given behavior is viewed as having moral implications, but it is likely that people in all cultures differentiate among moral, social conventional, and personal domains of functioning.