Historical Foundations of the Study of Child Development

From ancient Greece to the early years of the twentieth century, a number of profound thinkers observed and wrote about children. Their goals were like those of contemporary researchers: to help people become better parents, to improve children’s well-being, and to understand human nature. Unlike contemporary researchers, they usually based their conclusions on general philosophical beliefs and informal observations of a few children. Still, the issues they raised are sufficiently important, and their insights sufficiently deep, that their views continue to be of interest.

8

Early Philosophers’ Views of Children’s Development

Some of the earliest recorded ideas about children’s development were those of Plato and Aristotle. These classic Greek philosophers, who lived in the fourth century B.C.E., were particularly interested in how children’s development is influenced by their nature and by the nurture they receive.

Both Plato and Aristotle believed that the long-term welfare of society depended on the proper raising of children. Careful upbringing was essential because children’s basic nature would otherwise lead to their becoming rebellious and unruly. Plato viewed the rearing of boys as a particularly demanding challenge for parents and teachers:

Now of all wild things, a boy is the most difficult to handle. Just because he more than any other has a fount of intelligence in him which has not yet “run clear,” he is the craftiest, most mischievous, and unruliest of brutes.

(Laws, bk. 7, p. 808)

Consistent with this view, Plato emphasized self-control and discipline as the most important goals of education (Borstelmann, 1983).

Aristotle agreed with Plato that discipline was necessary, but he was more concerned with fitting child-rearing to the needs of the individual child. In his words:

It would seem…that a study of individual character is the best way of making education perfect, for then each [child] has a better chance of receiving the treatment that suits him.

(Nicomachean Ethics, bk. 10, chap. 9, p. 1180)

Plato and Aristotle differed more profoundly in their views of how children acquire knowledge. Plato believed that children have innate knowledge. For example, he believed that children are born with a concept of “animal” that, from birth onward, automatically allows them to recognize that the dogs, cats, and other creatures they encounter are animals. In contrast, Aristotle believed that all knowledge comes from experience and that the mind of an infant is like a blackboard on which nothing has yet been written.

Roughly 2000 years later, the English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) and the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) refocused attention on the question of how parents and society in general can best promote children’s development. Locke, like Aristotle, viewed the child as a tabula rasa, or blank slate, whose development largely reflects the nurture provided by the child’s parents and the broader society. He believed that the most important goal of child-rearing is the growth of character. To build children’s character, parents need to set good examples of honesty, stability, and gentleness. They also need to avoid indulging the child, especially early in life. However, once discipline and reason have been instilled, Locke believed,

authority should be relaxed as fast as their age, discretion, and good behavior could allow it…. The sooner you treat him as a man, the sooner he will begin to be one.

(Cited in Borstelmann, 1983, p. 20)

In contrast to Locke’s advocating discipline before freedom, Rousseau believed that parents and society should give children maximum freedom from the beginning. Rousseau claimed that children learn primarily from their own spontaneous interactions with objects and other people, rather than through instruction by parents or teachers. He even argued that children should not receive any formal education until about age 12, when they reach “the age of reason” and can judge for themselves the worth of what they are told. Before then, they should be allowed the freedom to explore whatever interests them.

9

Although formulated long ago, these and other philosophical positions continue to underlie many contemporary debates, including whether children should receive direct instruction in desired skills and knowledge or be given maximum freedom to discover the skills and knowledge for themselves, and whether parents should build their children’s character through explicit instruction or through the implicit guidance provided by the parents’ own behavior.

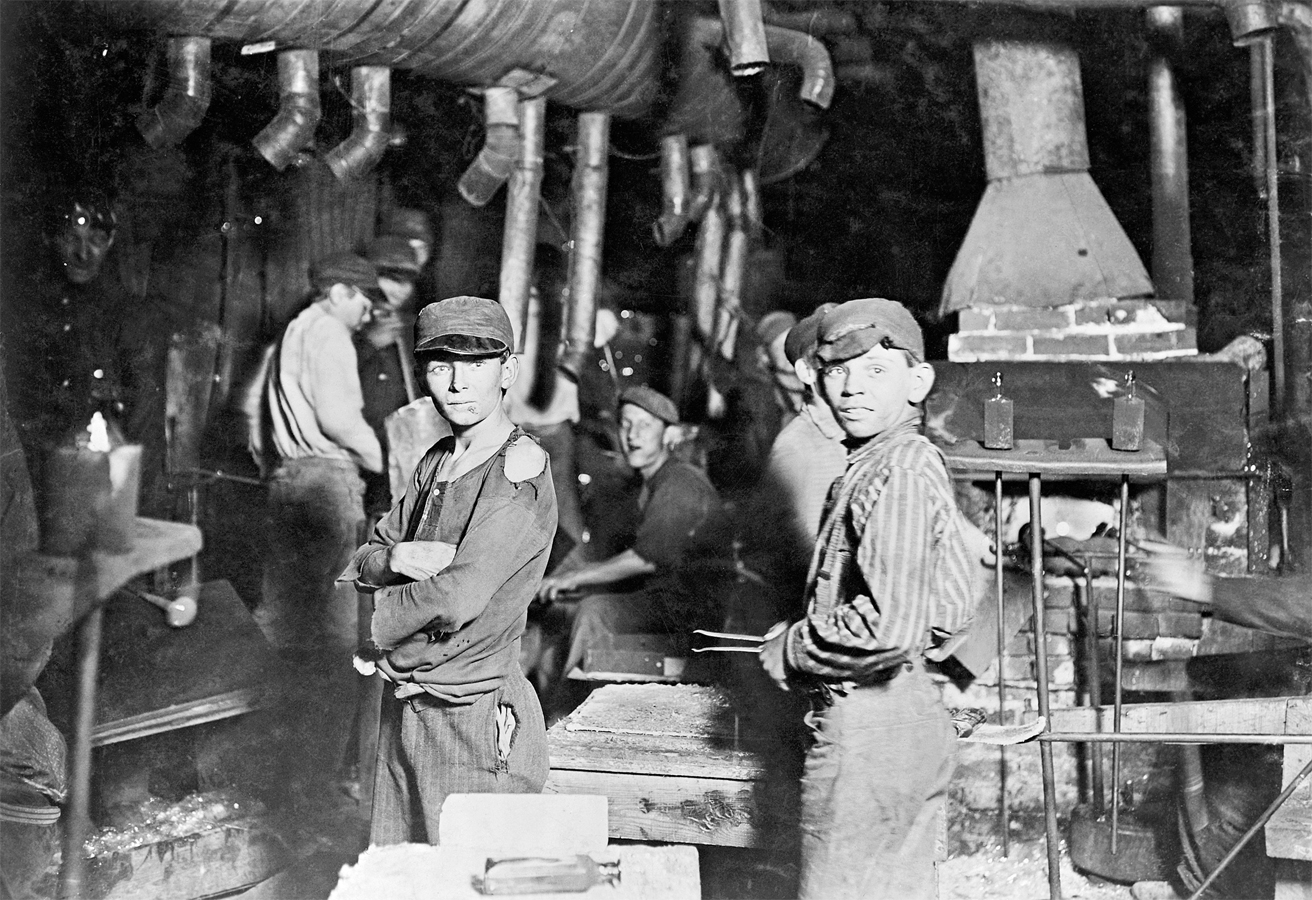

Social Reform Movements

Another precursor of the contemporary field of child psychology was early social reform movements that were devoted to improving children’s lives by changing the conditions in which they lived. During the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a great many children in Europe and the United States worked as poorly paid laborers with no legal protections. Some were as young as 5 and 6 years; many worked up to 12 hours a day in factories or mines, often in extremely hazardous circumstances. These harsh conditions worried a number of social reformers, who began to study how such circumstances affected the children’s development. For example, in a speech before the British House of Commons in 1843, the Earl of Shaftesbury noted that the narrow tunnels where children dug out coal had

very insufficient drainage [and] are so low that only little boys can work in them, which they do naked, and often in mud and water, dragging sledge-tubs by the girdle and chain…. Children of amiable temper and conduct, at 7 years of age, often return next season from the collieries greatly corrupted…with most hellish dispositions.

(Quoted in Kessen, 1965, pp. 46–50)

The Earl of Shaftesbury’s effort at social reform brought partial success—a law forbidding employment of girls and of boys younger than 10. In addition to bringing about the first child labor laws, this and other early social reform movements established a legacy of research conducted for the benefit of children and provided some of the earliest recorded descriptions of the adverse effects that harsh environments can have on children.

Darwin’s Theory of Evolution

Later in the nineteenth century, Charles Darwin’s work on evolution inspired a number of scientists to propose that intensive study of children’s development might lead to important insights into human nature. Darwin himself was interested in child development and in 1877 published an article entitled “A Biographical Sketch of an Infant,” which presented his careful observations of the motor, sensory, and emotional growth of his infant son, William. Darwin’s “baby biography”—a systematic description of William’s day-to-day development— represented one of the first methods for studying children.

Such intensive studies of individual children’s growth continue to be a distinctive feature of the modern field of child development. Darwin’s evolutionary theory also continues to influence the thinking of modern developmentalists on a wide range of topics: infants’ attachment to their mothers (Bowlby, 1969), innate fear of natural dangers such as spiders and snakes (Rakison & Derringer, 2008), sex differences (Geary, 2009), aggression and altruism (Tooby & Cosmides, 2005), and the mechanisms underlying learning (Siegler, 1996).

10

The Beginnings of Research-Based Theories of Child Development

At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the first theories of child development that incorporated research findings were formulated. One prominent theory, that of the Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud, was based in large part on his patients’ recollections of their dreams and childhood experiences. Freud’s psychoanalytic theory proposed that biological drives, especially sexual ones, are a crucial influence on development.

Another prominent theory of the same era, that of American psychologist John Watson, was based primarily on the results of experiments that examined learning in animals and children. Watson’s behaviorist theory argued that children’s development is determined by environmental factors, especially the rewards and punishments that follow the children’s actions.

By current standards, the research methods on which these theories were based were crude. Nonetheless, these early scientific theories were better grounded in research evidence than were their predecessors, and, as you will see later in the chapter, they inspired more sophisticated ideas about the processes of development and more rigorous research methods for studying how development occurs.

review:

Philosophers such as Plato, Aristotle, Locke, and Rousseau, as well as early scientific theorists such as Darwin, Freud, and Watson, raised many of the deepest issues about child development. These issues included how nature and nurture influence development, how best to raise children, and how knowledge of children’s development can be used to advance their welfare.