The Body: Physical Growth and Development

In Chapter 1, we emphasized the multiple contexts in which development occurs. Here we focus on the most immediate context for development—the body itself. Everything we think, feel, say, and do involves our physical selves, and changes in the body lead to changes in behavior. In this section, we present a brief overview of some aspects of physical growth, including some of the factors that can disrupt normal development. Nutritional behavior, a vital aspect of physical development, is featured as we consider the regulation of eating. We concentrate particularly on one of the consequences of poor regulation—obesity. Finally, we focus on the opposite problem—undernutrition.

Growth and Maturation

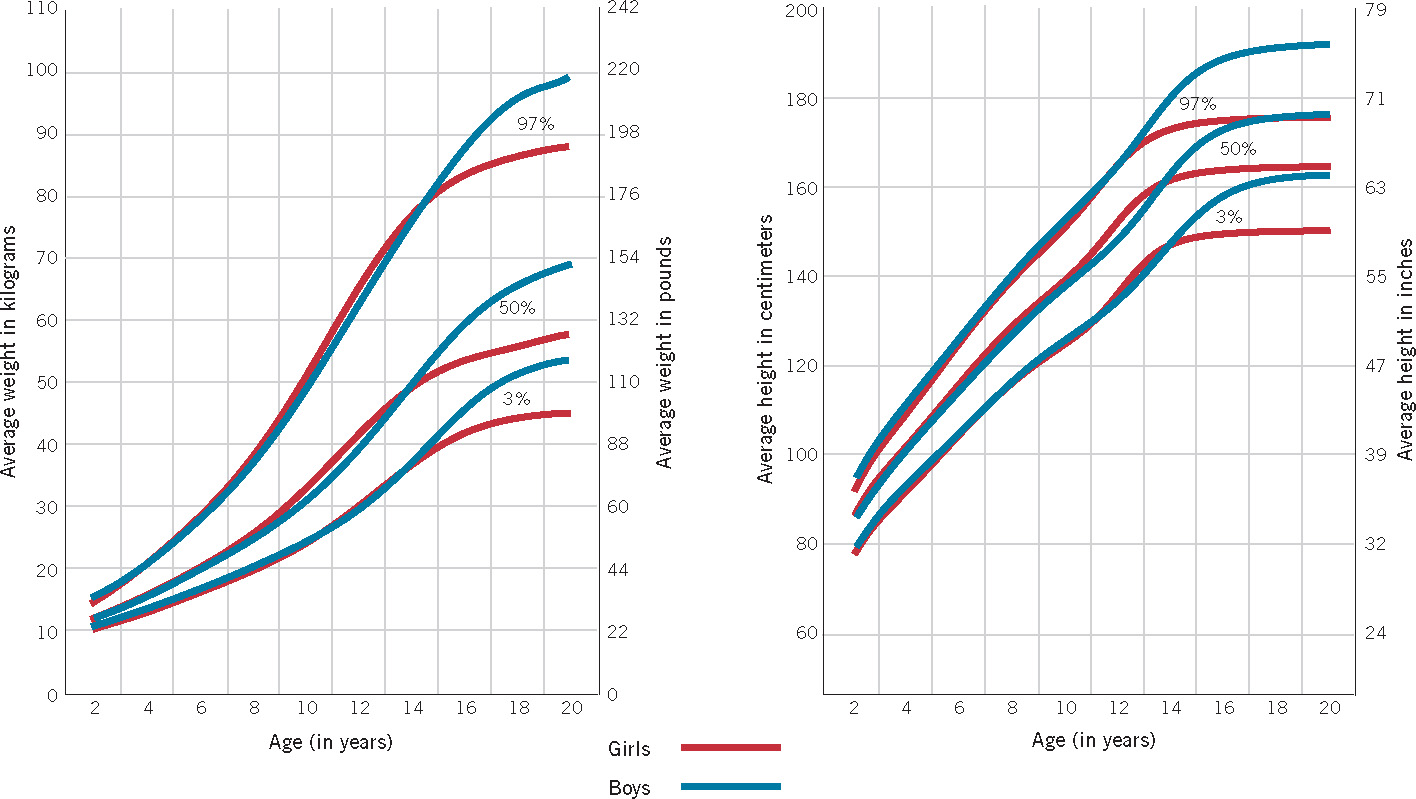

Compared with most other species, humans undergo a prolonged period of physical growth. The body grows and develops for 20% of the human life span, whereas mice, for example, grow during only 2% of their life span. Figure 3.11 shows the most obvious aspects of physical growth: we get 3 times taller and 15 to 20 times heavier between birth and age 20. The figure shows averages, of course, and there are obviously huge individual differences in height and weight, as well as in the timing of physical development.

120

Growth is uneven over time, as you can tell from the differences in the slopes in Figure 3.11. The slopes are steepest when the most rapid growth is occurring—in the first 2 years and in early adolescence. Early on, boys and girls grow at roughly the same rate, and they are essentially equal in height and weight until around 10 to 12 years of age. Then girls experience their adolescent growth spurt, at the end of which they are somewhat taller and heavier than boys. (Remember those awkward middle-school years when the girls towered over the boys, much to the discomfort of both?) Adolescent boys experience their growth spurt about 2 years after the girls, permanently passing them in both height and weight. Full height is achieved, on average, by around the age of 15½ for girls and 17½ for boys.

Growth is also uneven across the different parts of the body. Following the principle of cephalocaudal development described in Chapter 2, the head region is initially relatively large—fully 50% of body length at 2 months of age—but only about 10% of body length in adulthood. The gawkiness of young adolescents stems in part from the fact that their growth spurt begins with dramatic increases in the size of the hands and feet; it’s easy to trip over your own feet when they are disproportionately larger than the rest of you.

Body composition also changes with age. The proportion of body fat is highest in infancy, gradually declining thereafter until around 6 to 8 years of age. In adolescence, it decreases in boys but increases in girls, and that increase helps trigger the onset of menstruation. The proportion of muscle grows slowly until adolescence, when it increases dramatically, especially in boys.

Variability

secular trends marked changes in physical development that have occurred over generations

There is great variability across individuals and groups in all aspects of physical development. This variability in physical development is due to both genetic and environmental factors. Genes affect growth and sexual maturation in large part by influencing the production of hormones, especially growth hormone (secreted by the pituitary gland) and thyroxine (released by the thyroid gland). The influence of environmental factors is particularly evident in secular trends, marked changes in physical development that have occurred over generations. In contemporary industrialized nations, adults are several inches taller than their same-sex great-grandparents were. This change is assumed to have resulted primarily from improvements in nutrition and general health. Another secular trend in the United States today involves girls’ beginning to menstruate a few years earlier than their ancestors did, a change attributed to the general improvement in nutritional status of the population.

failure to thrive a condition in which infants become malnourished and fail to grow or gain weight for no obvious medical reason

Environmental factors can also play a role in disturbances of normal growth. For example, severe chronic stress, such as that associated with a home environment involving serious marital discord, alcoholism, or child abuse can impair growth by lowering the pituitary gland’s production of growth hormone (Powell, Brasel, & Blizzard, 1967). Children raised in institutions also have a higher risk of growth impairment, likely due to the combination of social stressors and poor nutrition (D. E. Johnson & Gunnar, 2011). A combination of genetic and environmental factors is apparently involved in failure to thrive, a condition in which infants become malnourished and fail to grow or gain weight for no obvious medical reason. Because the reason for a particular infant’s failure to thrive is often difficult to determine, treatment may range from hospitalization to dietary supplementation to behavioral interventions, such as rewards for positive eating behaviors (Jaffe, 2011).

121

Nutritional Behavior

The health of our bodies depends on what we put into them, including the amount and kind of food we eat. Thus, the development of eating or nutritional behavior is a crucial aspect of child development from infancy onward.

Infant Feeding

Like all mammals, human newborns obtain life-sustaining nourishment through suckling, although they require more assistance in this endeavor than do most other mammals. Throughout nearly the entire history of the human species, the only or primary source of nourishment for infants was breast milk. Mother’s milk has many virtues (J. Newman, 1995). It is naturally free of bacteria, strengthens the infant’s immune system, and contains the mother’s antibodies against infectious agents the baby is likely to encounter after birth.

There have also been suggestions in the literature that the fatty acids in breast milk have a positive effect on cognitive development, with some studies indicating higher IQ scores for children and adults who were breastfed as infants (for review, see Nisbett et al., 2012). The challenge in this area of research in the United States is that the choice to breastfeed is correlated with social class (due to factors ranging from maternal education to working conditions that make it difficult to nurse or pump breast milk on the job). However, several recent studies that controlled for social class still found cognitive benefits associated with breastfeeding. In one of those studies, mother–infant dyads were randomly assigned either to an intervention encouraging breastfeeding or to a control condition without intervention. The results indicated that prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding in infancy led to increased IQ scores at 6½ years of age (Kramer et al., 2008). Another study that examined genetic factors found that children who carry one of two specific alleles that regulate fatty acids showed a substantial cognitive benefit from breastfeeding, while individuals with a different allele showed a smaller benefit (Caspi et al., 2007). These results reflect the kind of genotype–environment interaction discussed earlier in this chapter, with the benefits of a particular environment (in this case, breast milk) delimited by the child’s genotype.

However, in spite of the well-established nutritional superiority of breast milk, as well as the fact that it is free, many infants in the United States are exclusively or predominantly formula-fed. Recent public health efforts have begun to shift this longtime feeding trend, by educating parents about the benefits of breast milk and encouraging employers to provide private space for working mothers to pump breast milk. Since these efforts were initiated, the number of newborns fed breast milk in the United States has increased annually and, by 2009, had risen to 76.9% of neonates (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). However, this good nutritional start was difficult for parents to maintain; by 6 months of age, only 47.2% of infants were still being breastfed, and by 12 months of age, only 25.5% were.

In developed countries, infant formula can support normal growth and development, although infants who are formula-fed have somewhat higher rates of infection than do those who are fed breast milk. In undeveloped countries, however, formula feeding can exact a costly toll. Much of the undeveloped world does not have safe water, so infant formula is often mixed with polluted water in unsanitary containers. Furthermore, poor, uneducated parents often dilute the formula in an effort to make the expensive powder last longer. In such circumstances, parents’ attempts to promote the health of their babies end up having the opposite effect (Popkin & Doan, 1990).

122

Development of Food Preferences and the Regulation of Eating

Food preferences are a primary determinant of what we eat throughout life, and some of these preferences are clearly innate. Infants display some of the same reflexive facial expressions that older children and adults display in response to three basic tastes: sweet, sour, and bitter. The first produces a hint of a smile; the second, a pucker; the third, a grimace (Rosenstein & Oster, 1988; Steiner, 1979). Newborns’ strong preference for sweetness is reflected both in their smiling in response to sweet flavors and in the fact that they will drink larger quantities of sweetened water than plain water. These innate preferences may have an evolutionary origin, since poisonous substances are often bitter or sour but almost never sweet. At the same time, recall from Chapter 2 that taste preferences can also be influenced by the prenatal environment, suggesting an important role for experience even in the earliest flavor preferences.

Infants’ taste sensitivity is evident in their reactions to their mother’s milk, which can take on the flavor of what she eats. Babies nurse longer and take more breast milk when their mother has ingested either garlic or vanilla flavors, but they drink less breast milk after she has downed a beer (Mennella & Beauchamp, 1993a, 1993b, 1996).

From infancy on, experience has a major influence on what foods children like and dislike and on what and how much they eat. For instance, preschool children’s liking for particular foods increases if they observe other children enjoying them (Birch & Fisher, 1996). Children’s eating is also influenced by what foods their parents encourage and discourage. This influence does not always work in the way the parents intend, however. For example, standard parental strategies of cajoling and bribing young children to eat new or healthier foods—“If you eat your spinach, you can have some ice cream”—can be doubly counterproductive. The most probable result is that the child will dislike the healthy food even more and have an even stronger preference for the sweet, fatty food used as a reward (Birch & Fisher, 1996).

Many parents become needlessly concerned with how much their young children eat. They might, however, put less effort into trying to control their children’s eating behavior if they realized that young children are actually quite good at regulating the amount of food they consume. Research has shown that preschool children adjust how much they eat at a given time based on how much they consumed earlier. For example, children were found to eat less for lunch if they had been served a snack earlier than if they had not had the snack (Birch & Fisher, 1996). (In contrast, a group of adults ate pretty much the same amount of a meal whether or not they had been served a snack earlier.)

In general, children whose parents try to control their eating habits tend to be worse at regulating their food intake themselves than are children whose parents allow them more control over what and how much they eat (S. L. Johnson & Birch, 1994). Parents’ overregulation of their children’s eating behavior can have continuing effects. Adults who reported that their parents used food to control their behavior were more likely to be struggling with their weight and with binge eating (Puhl & Schwartz, 2003).

Obesity

So many people have difficulty regulating their eating appropriately that the most common dietary problems in the United States are related to overeating and its many consequences. In an epidemic of obesity, one-third of American adults are currently considered obese (Ogden et al., 2012). It is an increasing problem, not just among Americans but also among indigenous people in many developing countries (Abelson & Kennedy, 2004). This situation exists largely because societies all over the world are increasingly adopting a “Western diet” of foods high in fat and sugar and low in fiber. Fast-food restaurants have proliferated around the globe; indeed, after Santa Claus, Ronald McDonald is the second most recognized figure worldwide (K. Brownell, 2004).

123

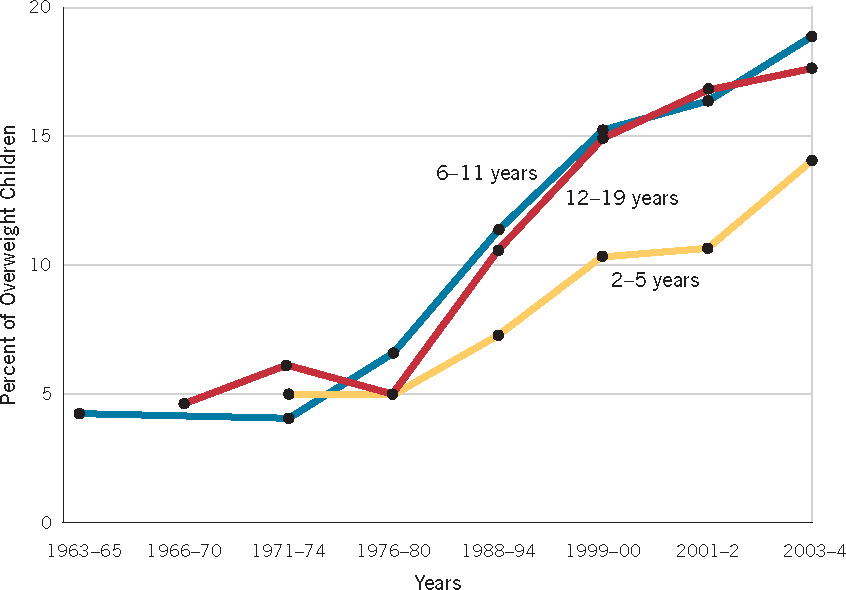

The proportion of American children and adolescents who are overweight has tripled in the past four decades (see Figure 3.12), with the increase being greatest for Latinos and African Americans. The outlook for these heavy children is troubling, because they are likely to struggle with weight problems throughout their lives. Furthermore, there is a good chance they will adopt a variety of unhealthy measures to fight their weight problems—skipping meals, fasting, smoking, taking diet pills, and even undergoing liposuction—all of which can lead to further health problems.

Two important questions need to be addressed: Why do some people but not others become overweight, and why is there an epidemic of obesity? Both genetic and environmental factors play roles. Genetic factors are reflected in the findings that (1) the weight of adopted children is more strongly correlated with that of their biological parents than with that of their adoptive parents, and (2) identical twins, including those reared apart, are more similar in weight than fraternal twins are (Plomin et al., 2013). Even the speed of eating, which is related both to how much is eaten in a given meal and to the weight of the eater, shows substantial heritability (Llewellyn et al., 2008). Thus, genes affect individuals’ susceptibility to gaining weight and how much food they eat in the first place, making it relatively difficult or easy for them to avoid becoming part of the obesity epidemic.

Environmental influences also play a major role in this epidemic, as is obvious from the fact that a much higher proportion of the population of the United States is overweight now than in previous times. Indeed, some have argued that becoming obese in the United States could be considered a normal response to the contemporary American taste for high-fat, high-sugar foods in ever larger portion sizes (K. D. Brownell, 2003).

A host of other factors fuel the ever expanding waistlines of today’s children. Children spend less time playing outside than their counterparts did in previous generations: fully half of today’s preschool-aged children spend less than an hour a day engaged in outdoor play (Tandon et al., 2012). Children today also get less exercise because they rarely walk or bike to school. At school, they frequently have no physical education programs or recess activities and often purchase cafeteria lunches consisting of high-fat foods (e.g., pizza, hamburgers) and high-calorie soft drinks. Young couch potatoes—many of whom spend more than 5 hours a day in front of the TV consuming junk food as they are subjected to a barrage of advertisements for more high-fat, nonnutritious fast food—are much more likely to be obese than are children who watch for 2 hours or fewer (T. N. Robinson, 2001). In addition, many U.S. families often dine out at fast-food or “all you can eat” buffet-style restaurants where they consume large portions of relatively high-calorie foods (Krishnamoorthy, Hart, & Jelalian, 2006). Finally, unhealthy foods are often less expensive and more readily available than healthier foods, especially in inner-city areas that lack full-service supermarkets. In such areas, known as “food deserts,” poorer residents often must rely on convenience stores that stock primarily high-calorie prepackaged foods, making it difficult even for motivated parents to provide healthy foods to their children.

124

Obesity puts children and adolescents at risk for a wide variety of serious health problems, including heart disease and diabetes. In addition, many obese youth suffer the consequences of negative stereotypes and discrimination in a variety of areas, even college admissions (M. A. Friedman & Brownell, 1995). Overweight children and teenagers suffer a variety of other social problems as well. For example, overweight adolescents tend to be either socially isolated or on the fringe of their social networks (Strauss & Pollack, 2003). Also, in a large-scale survey of middle school and high school students, teens who reported being teased about their weight had considered suicide more often than had their slimmer peers (M. Eisenberg, Neumark-Sztainer, & Story, 2003).

There is, unfortunately, no easy cure for obesity in children. However, some hope for the general obesity problem comes from the fact that public awareness is now focused on the severity of the problem and the variety of factors that contribute to it. Many schools have begun serving more nutritious, less caloric foods, including those available in vending machines, and fast-food chains have begun to include at least some low-calorie options on their menus. Prominent national figures, such as First Lady Michelle Obama, have targeted childhood obesity as a key public health issue, raising hope that campaigns focused on healthy eating and exercise will help families make positive lifestyle choices. Another helpful step, proposed by the Institute of Medicine (2004), would be for the food, beverage, and entertainment industries to discontinue targeting their advertising of high-fat, high-sugar foods and drinks to children and adolescents.

Undernutrition

Video: Malnutrition and Children in Nepal

At the same time that many people in relatively rich countries are overeating their way to poor health, the health of people in developing nations is compromised by their not getting enough to eat. Fully one-fourth of all children (and 40% of those younger than 5) living in these countries are undernourished. The nutritional deficits they experience can involve an inadequate supply of total calories, of protein, of vitamins and minerals, or any combination of these deficiencies. Severe malnutrition of infants and young children is most common in developing and/or war-torn countries. Analyses of child mortality data suggest that suboptimum nutrition (including nonexclusive breastfeeding) is an underlying cause of 35% of child deaths worldwide (R. E. Black et al., 2008).

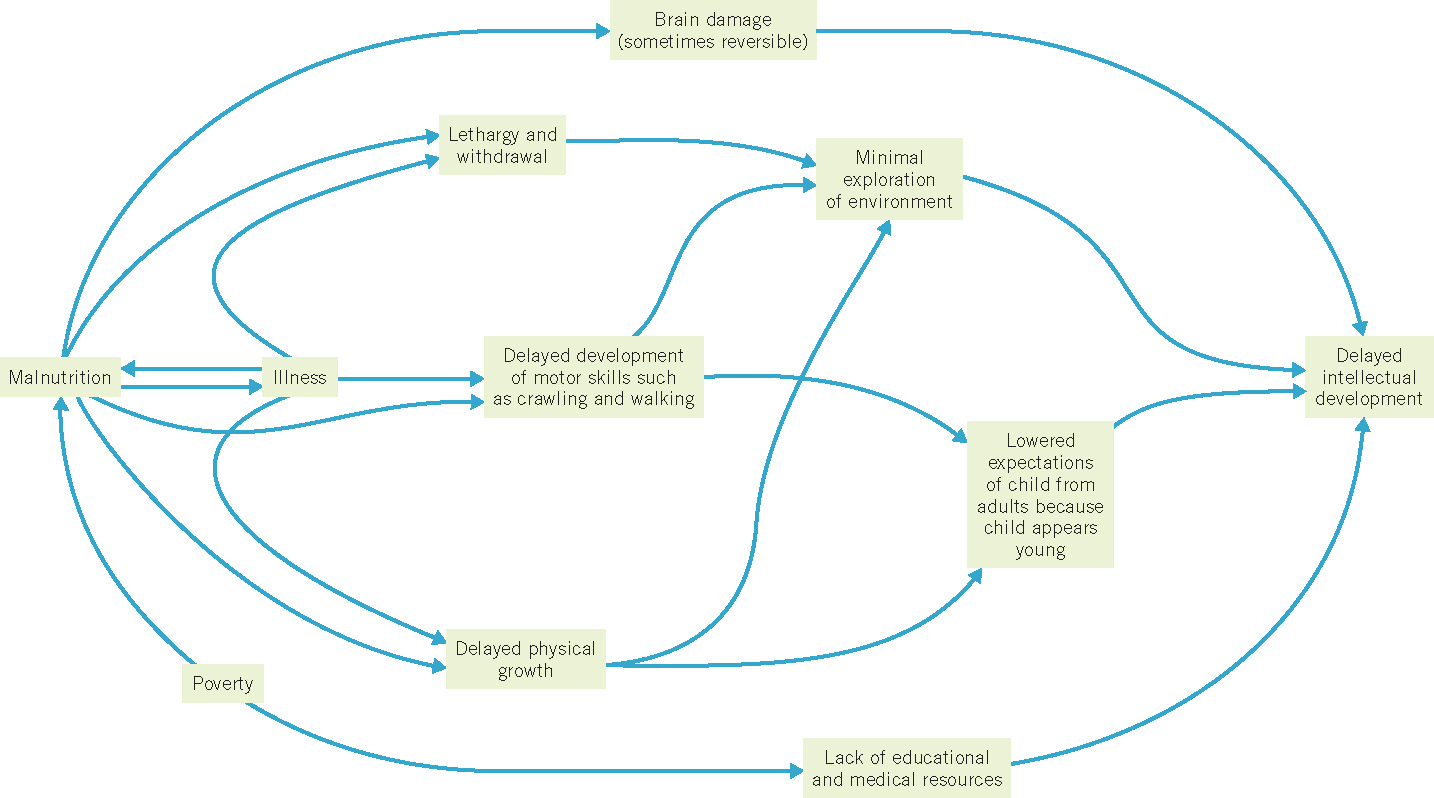

Undernutrition and malnutrition are virtually always associated with poverty and myriad related factors, ranging from limited access to health care (the primary cause in the United States) to warfare, famine, and natural disasters. The interaction of malnutrition with poverty and other forms of deprivation adversely affects all aspects of development. Figure 3.13 presents a model of how the complex interaction of these multiple factors impairs cognitive development (J. L. Brown & Pollitt, 1996). As you can see, malnutrition can have direct effects on the structural development of the brain, general energy level, susceptibility to infection, and physical growth. With inadequate energy, malnourished children tend to reduce their energy expenditure and withdraw from stimulation, making them quiet and passive in general, less responsive in social interactions, less attentive in school, and so on. Apathy, slowed growth, and delayed development of motor skills also retard the children’s exploration of the environment, further limiting their opportunities to learn.

125

Can anything be done to help malnourished and undernourished youngsters? Because so many interacting factors are involved in the problem, addressing it effectively is not easy—but neither is it impossible, as shown by several large-scale intervention efforts throughout the world. For example, in one long-term project led by Ernesto Pollitt in Guatemala, a high-protein dietary supplement administered starting in infancy correlated with an increase in performance on tests of cognitive functioning in adolescence (Pollitt et al., 1993). Follow-ups on the participants in adulthood produced strong evidence for the continuing benefits of dietary supplements 25 years after the intervention (Maluccio et al., 2009). Although it is possible to improve the developmental status of malnourished children, it would be better, both for the children themselves and for society in general, to prevent the occurrence of malnutrition in the first place. As Brown and Pollitt (1996) note: “On balance, it seems clear that prevention of malnutrition among young children remains the best policy—not only on moral grounds but on economic ones as well” (p. 702).

126

review:

Sound nutritional behavior is vital to general health. Preferences for certain foods are evident from birth on, and, as children develop, what they choose to eat is influenced by many factors, including the preferences of their friends and their parents’ attempts to influence their eating behavior. Obesity among both adults and children has increased dramatically in the United States and much of the rest of the world in recent decades, as exposure to rich foods in large portions has increased and physical activity has decreased. However, throughout the world, the most common nutritional problem is undernutrition, which is very closely associated with poverty. The combination of malnutrition and poverty is particularly devastating to development.