Learning Theories

I imagine the mind of children as easily turned this or that way, as water itself.

—John Locke

As you may recall from Chapter 1, the empiricist philosopher John Locke believed that experience shapes the nature of the human mind. The intellectual descendants of Locke are psychologists who consider learning from experience to be the primary factor in social and personality development.

349

View of Children’s Nature

In contrast to Freud’s emphasis on the role of internal forces and subjective experience, most learning theorists have emphasized the role of external factors in shaping personality and social behavior. They have often made very bold claims about the extent to which development can be guided by how people reward, or reinforce, certain of children’s behaviors and punish or ignore others. More contemporary learning theorists have emphasized the importance of cognitive factors and the active role children play in their own development.

Central Developmental Issues

The primary developmental question on which learning theories take a unanimous stand is that of continuity/discontinuity: they all emphasize continuity, proposing that the same principles control learning and behavior throughout life and that therefore there are no qualitatively different stages in development. Like information-processing theorists, learning theorists focus on the role of specific mechanisms of change—which, in their view, involve learning principles, such as reinforcement and observational learning. They believe that children become different from one another primarily because they have different histories of reinforcement and learning opportunities. The theme of research and children’s welfare is also relevant here in that therapeutic approaches based on learning principles have been widely used to treat children with a variety of problems.

Watson’s Behaviorism

John B. Watson (1878–1958), the founder of behaviorism, believed that children’s development is determined by their social environment and that learning through conditioning is the primary mechanism of development (see Chapter 5, pages 201–202). He also believed that psychologists should study only objectively verifiable behavior, not the “mind.”

The extent of Watson’s (1924) faith in the power of conditioning is clear in his famous boast:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in, and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select—doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and yes, even beggar man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors.

(p. 104)

On a much less ambitious scale, Watson demonstrated the power of classical conditioning in a famous—and by present standards, unethical—experiment with a 9-month-old infant referred to as “Little Albert” (Watson & Rayner, 1920). Watson first exposed Little Albert to a perfectly nice white rat in the laboratory. Initially, Albert reacted positively to the rat. On subsequent exposures, however, the researchers repeatedly paired the presentation of the rat with a loud noise that clearly frightened Albert. After a number of such pairings, Albert became afraid of the rat itself.

Our everyday lives are filled with examples of conditioned responses. Infants and young children, for example, often show fear at the sight of a doctor or nurse in a white coat, based on their previous association between people wearing white coats and painful injections. (To counteract this problem, modern pediatricians often sport lab coats with cheerful designs, hoping to elicit a positive response in their young patients.)

350

systematic desensitization a form of therapy based on classical conditioning, in which positive responses are gradually conditioned to stimuli that initially elicited a highly negative response. This approach is especially useful in the treatment of fears and phobias.

Watson’s work on classical conditioning laid the foundation for treatment procedures that are based on the opposite process—the deconditioning, or elimination, of fear. A student of Watson’s (M. C. Jones, 1924) treated 2-year-old Peter, who was deathly afraid of white rabbits (as well as white rats, white fur coats, white feathers, and a variety of other white things). To decondition Peter’s fear, the experimenter first gave him a favorite snack. Then, as Peter ate, a white rabbit in a cage was very slowly brought closer and closer to him—but never close enough to make him afraid. After repeatedly being exposed to the feared object in a context that was free of distress and provided the positive experience of a snack, Peter got over his fear. Eventually, he was even able to pet the rabbit. This approach, now known as systematic desensitization, is still widely used to rid people of fears and phobias of everything from dogs to dentists.

Believing that he had established the power of learning in development, Watson placed the responsibility for guiding children’s development squarely on the shoulders of their parents. In his child-rearing manual, Psychological Care of Infant and Child (1928), he offered parents stern advice for fulfilling this responsibility. One particular piece of Watson’s advice that was widely adopted in the United States was to put infants on a strict feeding schedule. The idea was that the baby would become conditioned to expect a feeding at regular intervals and therefore would not cry for attention in between. To help implement this and other of his strict regimens, Watson advised parents to achieve distance and objectivity in their relations with their children (just as he exhorted psychologists to be objective in their research):

Treat them as though they were young adults. Dress them, bathe them with care and circumspection. Let your behavior always be objective and kindly firm. Never hug and kiss them, never let them sit on your lap. If you must, kiss them once on the forehead when they say good night. Shake hands with them in the morning. Give them a pat on the head if they have made an extraordinarily good job on a difficult task. Try it out. In a week’s time you will find how easy it is to be perfectly objective with your child and at the same time kindly. You will be utterly ashamed of the mawkish, sentimental way you have been handling it.

(pp. 81–82)

Watson’s overly strict child-rearing advice gradually fell from favor with the publication and widespread success of Dr. Benjamin Spock’s The Common Sense Guide to Baby and Child Care, first published in 1946 (Spock’s thinking about early development and child rearing was very strongly influenced by Freud). However, Watson’s behaviorist emphasis on the environment as the key factor in determining behavior persisted in the work of B. F. Skinner.

Skinner’s Operant Conditioning

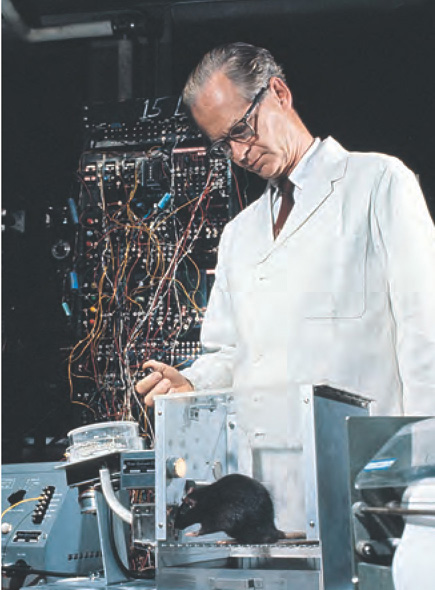

B. F. Skinner (1904–1990) was just as forceful as Watson in proposing that behavior is under environmental control, once claiming that “a person does not act upon the world, the world acts upon him” (Skinner, 1971, p. 211). As described in Chapter 5, a major tenet of Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning is that we tend to repeat behaviors that lead to favorable outcomes—that is, reinforcement—and suppress those that result in unfavorable outcomes—that is, punishment. Skinner believed that everything we do in life—every act—is an operant response influenced by the outcomes of past behavior.

351

Skinner’s research on the nature and function of reinforcement led to many discoveries, including two that are of particular interest to parents and teachers. One is the fact that attention can by itself serve as a powerful reinforcer: children often do things “just to get attention” (Skinner, 1953, p. 78). Thus, the best strategy for discouraging a child who throws temper tantrums from continuing to do so is to ignore that behavior whenever it occurs. The popular behavior-management strategy of time-out, or temporary isolation, involves systematically withdrawing attention and thereby removing the reinforcement for inappropriate behavior, with the goal of extinguishing it.

When the toddler son of one of the authors first graduated to a “big-boy bed,” he repeatedly got up after having been put to bed, using one pretext after another to join his parents. This undesirable behavior was extinguished in just a few nights by his father, who sat in a chair outside the bedroom door. Every time the child appeared, his father gently, but firmly and silently, put him back in his bed. The key to this successful intervention was the fact that there was no reinforcement for getting out of bed—no talking, no yelling, no drink of water, no interaction of any sort—in short, none of the potent reinforcers that parental attention provides.

intermittent reinforcement inconsistent response to the behavior of another person, for example, sometimes punishing an unacceptable behavior and sometimes ignoring it

A second important discovery that Skinner made is the great difficulty of extinguishing behavior that has been intermittently reinforced, that is, that has sometimes been followed by reward and sometimes not. As Skinner discovered in his research with animals, intermittent reinforcement makes behaviors resistant to extinction: if the reward for a behavior is totally withdrawn following intermittent reinforcement, the behavior persists longer than it would if it had previously been consistently reinforced. In effect, if a given behavior is not rewarded every time it is performed, an animal is likely to maintain the expectation that the next performance of the behavior may produce the reward.

Parents often encourage unwanted behavior in their children by inadvertently applying intermittent reinforcement. They valiantly try not to reward their children’s whiny or aggressive demands, but—being human—they sometimes give in. Such intermittent reinforcement is very powerful: if a parent who had occasionally given in to whining never did so again, the child would nevertheless continue to resort to whining for a long time, assuming that because it worked in the past, it might work again. The intermittent-reinforcement effect is one reason most children have at least a few persistent bad habits. Part of the effectiveness of the bedtime example described above was due to the total consistency of the father’s behavior.

behavior modification a form of therapy based on principles of operant conditioning in which reinforcement contingencies are changed to encourage more adaptive behavior

Skinner’s work on reinforcement has led to a form of therapy known as behavior modification, which has proven quite useful for changing undesirable behaviors. A simple example of this approach involved a preschool child who spent too much of his time in solitary activities. Observers noticed that the boy’s teachers were unintentionally reinforcing his withdrawn behavior: they talked to him and comforted him when he was alone but tended to ignore him when he played with other children. The boy’s withdrawal was modified by reversing the reinforcement contingencies: the teachers began paying attention to the boy whenever he joined a group but ignored him whenever he withdrew. Soon the child was spending most of his time playing with his classmates (F. R. Harris, Wolf, & Baer, 1967).

352

Social Learning Theory

Social learning theory, like other learning theories, attempts to account for personality and other aspects of social development in terms of learning mechanisms. However, in assessing the influence of the environment on children’s development, social learning theory emphasizes observation and imitation, rather than reinforcement, as the primary mechanisms of development. Albert Bandura (1977, 1986), for example, has argued that most human learning is inherently social in nature and is based on observation of the behavior of other people. Children learn rapidly and efficiently simply from watching what other people do and then imitating them. Although direct reinforcement can increase the likelihood of imitation, it is not necessary for learning. Children can learn from symbolic models, that is, from reading books and from watching TV or movies, in the absence of any reinforcement for their behavior (see Box 9.1).

Video: Observational Learning of Aggression: Bandura's Bobo Doll Study

Box 9.1: a closer look: BANDURA AND BOBO

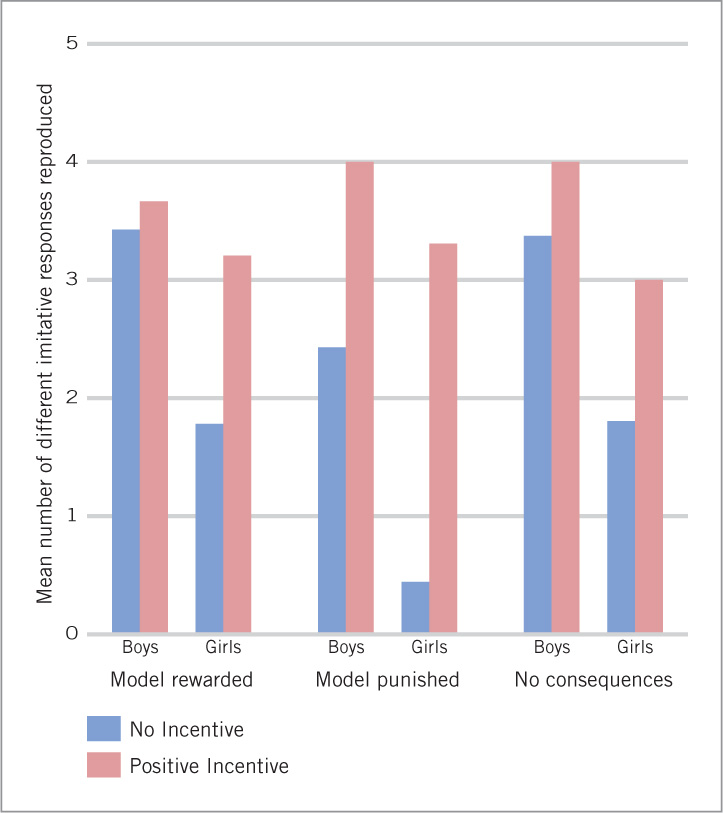

A series of classic studies by Albert Bandura and his colleagues (Bandura, 1965; Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1963) will give you a good sense of the kind of questions and methods that typify social learning theory research. The investigators began by having preschool children individually watch a short film in which an adult model performed highly unusual aggressive actions on a Bobo doll (an inflatable toy, with a weight in the bottom so it pops back up as soon as it is knocked down). The model punched the doll, hit it with a mallet while shouting “Sockeroo,” threw balls at it while shouting “Bang bang,” and so on.

vicarious reinforcement observing someone else receive a reward or punishment

In one study, three groups of children observed the adult model receive different consequences for these aggressive behaviors. One group saw the model receive rewards (an adult gave the model candy and soda and praised the “championship performance”). Another group saw the model punished (scolded). The third group saw the model experience no consequences. The question was whether vicarious reinforcement—observing someone else receive a reward or a punishment—would affect the children’s subsequent reproduction of the behavior. After viewing the film, each child was left alone in a playroom with a Bobo doll, and hidden observers recorded whether the child imitated what he or she had seen the model do. Later, whether or not they had imitated the model, the children were offered juice and prizes to reproduce all the model’s actions that they could remember.

The results are shown in the figure. The children who had seen the model punished imitated the behavior less than did those in the other two groups. However, the children in all conditions had learned from observing the model’s behavior and remembered what they had seen; when offered rewards to reproduce the aggressive actions, they did so, even if they had not spontaneously performed them in the initial test.

One particularly interesting feature of this research is the gender differences that emerged: boys were more physically aggressive toward the Bobo doll than girls were. However, the girls had learned as much about the modeled behaviors as the boys had, as shown by their increased level of imitation when offered a reward. Presumably, boys and girls generally learn a great deal about the behaviors considered appropriate to both genders but inhibit those they believe to be inappropriate for their own gender.

This classic research thus demonstrates that children can quickly acquire new behaviors simply as a result of observing others, that their tendency to reproduce what they have learned depends on whether the person whose actions they observed was rewarded or punished, and that what children learn from watching others is not necessarily evident in their behavior.

353

354

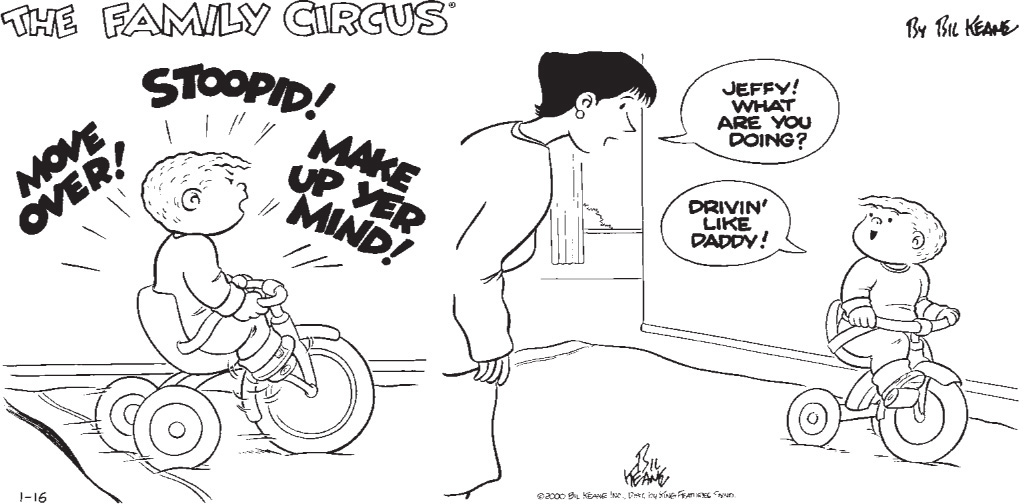

Over time, Bandura increasingly emphasized the cognitive aspects of observational learning, eventually renaming his view “social cognitive theory.” Observational learning clearly depends on basic cognitive processes of attention to others’ behavior, encoding what is observed, storing the information in memory, and retrieving it at some later time in order to reproduce the behavior observed earlier. Thanks to observational learning, many young children know quite a bit about adult activities—such as driving a car (you insert and turn the ignition key, press on the accelerator, turn the steering wheel)—long before being allowed to engage in them themselves.

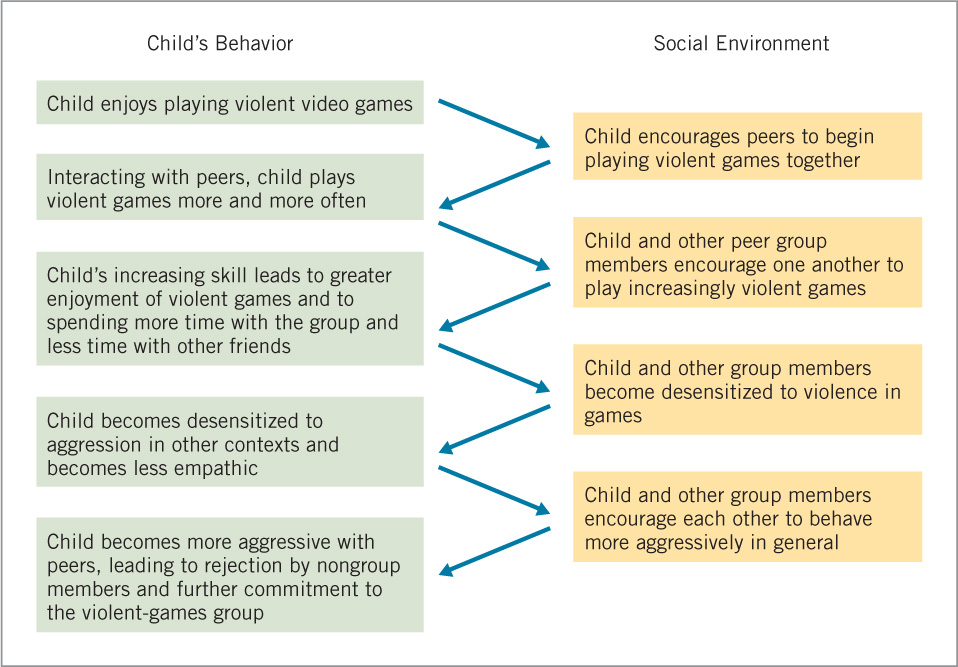

reciprocal determinism Bandura’s concept that child–environment influences operate in both directions; children are affected by aspects of their environment, but they also influence the environment

Unlike most learning theorists, Bandura emphasized the active role of children in their own development, describing development as a reciprocal determinism between children and their social environment. The basic idea of this concept is that every child has characteristics that lead him or her to seek particular kinds of interactions with the external world. The child is affected by these interactions in ways that influence the kinds of interactions he or she seeks in the future. The concept is illustrated in Figure 9.1, which depicts how a child’s aggressive tendencies can have an impact on the child’s playmates and, in turn, be shaped by how those playmates respond.

perceived self-efficacy an individual’s beliefs about how effectively he or she can control his or her own behavior, thoughts, and emotions in order to achieve a desired goal

Bandura has also emphasized the importance of a cognitive factor he calls perceived self-efficacy—a person’s beliefs about how effectively he or she can control his or her own behavior, thoughts, and emotions in order to achieve a desired goal (Bandura, 1997; Bandura et al., 2003). For example, your perceived self-efficacy for affect regulation has to do with your beliefs about how well you can manage your emotional life. In terms of positive affect, your perceived self-efficacy includes your sense of your ability to express affection for another person and to feel satisfaction with your accomplishments. In terms of negative affect, it includes how well you think you can manage fear or anger in the face of threats and provocations and calm yourself after being upset. Perceived academic self-efficacy concerns students’ beliefs about how well they can regulate their learning activities, master their coursework, and fulfill their own and others’ expectations. A person with high academic self-efficacy tends, for example, to arrange the environment to be conducive to effective studying and, when necessary, to seek information and help from teachers, parents, and peers.

An individual’s perceptions of self-efficacy in various domains often operate in concert (Bandura et al., 2003). For example, adolescents with low self-efficacy for affect regulation tend to also have low self-efficacy with respect to managing their academic performance. In other words, students who lack confidence in their ability to regulate their emotional life see themselves as incapable of taking charge of their academic work. They are also more likely to engage in delinquent behavior (lying, cheating, theft, aggression, and so forth), presumably because feeling incapable of regulating their own behavior undermines their ability to resist negative peer pressures.

355

Current Perspectives

In contrast to psychoanalytic theories, learning theories are based on principles derived from experiments. As a result, they allow explicit predictions that can be empirically tested. Partly for this reason, they have inspired an enormous amount of research yielding a great deal of understanding about parental socialization practices and how children learn social behaviors in many domains. They have also led to important practical applications, including clinical procedures of systematic desensitization and behavior modification. The primary weakness of the learning approach is its lack of attention to biological influences and, except for Bandura’s theory, to the role of cognition in influencing behavior.

Kismet’s designers took learning theories of development to heart from the very beginning by giving the robot the crucial capacity for learning that is mediated by humans. The emotional and verbal reactions of people to its behaviors instruct Kismet regarding the appropriateness of what it has done. Kismet also has the capacity to acquire new behaviors by modeling what it “sees” and “hears” humans do. Kismet’s ability to learn from people is a crucial aspect of what makes it seem truly sociable. What would it take for Kismet to acquire a sense of what Bandura refers to as perceived self-efficacy? Could Kismet ever form “beliefs” about what it can and cannot do and base its behavior on those beliefs?

356

review:

Learning theorists assume that social development is primarily attributable to what children learn through their interactions with other people. Early behaviorists such as Watson and Skinner emphasized the reinforcement history of the individual, believing that children’s social behavior is shaped by the pattern of rewards and punishments they receive from others. Social learning theorists, most prominently Albert Bandura, emphasize the role of cognition in social learning, noting that children learn a great deal simply from observing the behavior of other people, including the ramifications of observed behavior (such as the rewards and punishments observed in the Bobo doll experiments described in Box 9.1). Perceived self-efficacy affects the behavior of children in many ways, including how well they think they can manage their emotions and schoolwork. Learning approaches have inspired a variety of treatment methods useful for a wide range of behavioral problems in children.