Sheila McClain, The Fitness Culture

| Sheila McClain | The Fitness Culture |

ORIGINALLY WRITTEN by Sheila McClain for her first-year college composition course, this essay speculating about the causes of the fitness culture has been updated to reflect current statistics. Before reading, reflect on your own attitudes about exercise:

- How would you respond to the poll reported on in paragraph 3? How much do you think exercising can impact health and attractiveness?

- What do you do, if anything, to achieve physical fitness? What do your friends typically do?

As you read, consider the questions in the margin. Your instructor may ask you to post your answers to a class discussion board or to answer them in a writing journal.

Basic Features

A Well-Presented Subject

A Well-Supported Causal Analysis

An Effective Response to Objections and Alternative Causes

A Clear, Logical Organization

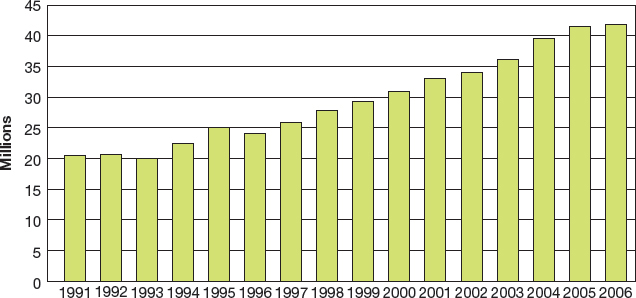

1The exercise and fitness industry used to cater to a small, select group of hard-core athletes and bodybuilders. Now, physical fitness has an increasingly broad appeal to people of all ages, and the evidence can be seen everywhere. You cannot turn on the television without seeing an infomercial featuring the latest exercise machine. Sales of fitness equipment for home use—from home gyms to DVDs and fitness games like the Wii Fit—have been booming since the early 1990s. Fitness club membership, according to the International Health, Racquet and Sportsclub Association (IHRSA), jumped from 20 million in 1991 to over 40 million in 2006 (“U.S. Health Club Membership”; see fig. 1). Although club membership did not change significantly between 2006 and 2009, it leapt another 10 percent to 50.2 million in 2010 (“U.S. Health Club Membership”). As of September 30, 2011, as many as 16 percent of Americans were members of a health club (“IHRSA”).

Question

[Answer Question]

Question

[Answer Question]

2Research linking fitness to health and longevity has led to the growth of the “fitness culture” in America. Numerous clinical studies and scientific reports have been publicized confirming that exercise, together with a proper diet, helps prevent heart disease as well as many other serious health problems, and may even reverse the effects of certain ailments. According to Marc Leepson, historian and former staff writer for the Congressional Quarterly, “clinical studies in 1989 done by the United States Preventive Services Task Force, a government appointed panel of experts, found ‘a strong association between physical activity and decreased risk of several medical conditions, as well as overall mortality’” (Leepson). Subsequent research has just heightened the association between fitness and longevity. A recent study reported in Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association found that keeping fit or becoming more fit, regardless of your weight, can reduce your risk of dying. On the other hand, reducing your fitness correlated with increased risk (“Physical”). The federal government has tried to increase awareness about the benefits of fitness, including by promoting workplace wellness programs. “Hundreds of firms established in-house fitness centers or contracted with local gyms,” because, as historian Marc Stern points out, exercise was assumed “to increase productivity, reduce absenteeism, enable recruitment and retention, and improve morale” (3–4).

3As a nation, we have become much more aware of the ways that physical fitness contributes to health and longevity. In 2006, the Pew Research Center found that 86 percent of adults surveyed thought that “exercising for fitness improves a person’s odds of a long and healthy life by ‘a lot.’ And, about six in ten believe that exercising has ‘a lot’ of impact on a person’s attractiveness” (Table 1). Fifty-seven percent claim to do “some kind of exercise program to keep fit.” Even so, “among these regular exercisers, about two-thirds (65%) admit that they aren’t getting as much exercise as they should.”

| How much do you think | ||

| exercising can impact . . . | a long and healthy life | attractiveness |

| A lot | 86% | 59% |

| A little | 11 | 31 |

| Not at all | 1 | 6 |

| It depends (vol.) | 1 | 2 |

| Don’t know | 1 | 2 |

| 100 | 100 | |

| Source: Pew Research Center | ||

Question

[Answer Question]

Question

[Answer Question]

4 We all know why we should exercise, but why join a fitness club? Some of the answers may surprise you—such as to be part of a community, to reduce stress, to improve your body image, and simply to have fun. One reason people join fitness clubs is to fulfill the basic human desire for a sense of community and belonging. People today are more likely than in the past to stay at home, as Harvard professor Robert D. Putnam argued in his best-selling book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. As a result, Americans have become more solitary. At the same time, they are growing more aware that they must stay fit to be healthy and realize that health clubs can have the added advantage of bringing them into contact with other people. Psychology professors Jasper A. J. Smits and Michael W. Otto, in their new book, Exercise for Mood and Anxiety, cite research showing that “one of the benefits of regular physical activity is feeling more connected to others” (7). Glenn Colarossi—a widely quoted authority on fitness, who has a master’s degree in exercise physiology and is co-owner of the Stamford (Connecticut) Athletic Club—adds his own anecdotal evidence about why people join clubs: “People like to belong to something. They like the support and added incentive of working out with others” (qtd. in Glenn). Furthermore, Catherine Larner, a writer on health and lifestyle issues, considers “increasing one’s circle of friends” among the benefits of going to the gym (1). Group exercise also fosters positive peer pressure that keeps people going when they might give up were they exercising alone at home.

Question

[Answer Question]

Question

[Answer Question]

5Another even more surprising cause of the popularity of fitness clubs may be the anxiety about terrorism following 9/11. As Mary Sisson notes in an article in Crain’s New York Business, health club chains saw an increase in revenues immediately after 9/11 and even expanded, one of them opening four new clubs, despite an economic downturn for most other industries. Sisson offers several plausible reasons why fear from the threat of terrorism on top of the normal stresses of modern life cause people to exercise more and to do so together: (1) under stressful conditions, people want the sense of community provided by gyms and classes; (2) working out gives people a sense of empowerment that counteracts feelings of helplessness; (3) traveling less provided many people with more leisure time to fill after 9/11; and (4) people make personal reassessments after a major catastrophe—such as the woman who realized how out-of-shape she was and joined a gym after descending forty flights of stairs to evacuate the World Trade Center.

Question

[Answer Question]

6Body image is a more predictable cause but may not actually play as central a role as most people think it does. A cynical friend of mine thinks that the fitness culture is fueled by women who are less interested in reducing their stress, improving their health, or joining a community than they are in wanting to look like the idealized images of celebrities and models they see in the media. I tried out this idea on my exercise physiology professor, and she agreed that some people—men as well as women—are motivated to begin exercise programs by the desire to reshape their bodies. The Pew Research Center poll showing people’s opinions about the impact of exercising on attractiveness also seems to support this cause (see Table 1). However, my professor doubted that it could explain the huge increase in attendance at health clubs, because research in her field has shown that people with unrealistic goals are more likely to become discouraged easily and drop out of fitness classes (Harton). Skepticism about this cause is also evident in research by Laura Brudzynski and William P. Ebben, published in the International Journal of Exercise Science, showing that “body image may act as a motivator to exercise” but can also be “a barrier to exercise,” particularly for those with a negative body image (15). So perhaps body image is not as significant a cause as many people assume.

Question

[Answer Question]

Question

[Answer Question]

7A final cause worth noting is that fitness is becoming a lifestyle choice. As attitudes toward exercise are changing, health clubs may be becoming associated with fun instead of hard work. “No pain, no gain” used to be synonymous with exercise. But today exercise comes in many different forms, many of which are more engaging and gentler than in the past. The variety may also appeal to a wider range of people. Consider classes in belly dancing (you know what that is), strip tease aerobics (look it up!), and spinning (indoor group stationary cycling, led by an instructor)—these are just a few examples. David J. Glenn, writing in a business journal, points to the impact of these changing attitudes: “People look to personal fitness as a lifestyle and a way to enjoy life, not as a way to look like Arnold Schwarzenegger.” Gabriela Lukas, a New Yorker who has been exercising regularly since 2001, finds it emotionally satisfying and says it makes her “feel alive” (qtd. in Sisson). When people are having fun, they are more likely to stick with exercise long enough to experience the body’s release of endorphins commonly known as a “runner’s high.” More and more people are changing their attitudes about physical fitness as they recognize that they feel better, have more energy, and are actually improving the quality of their lives by exercising regularly.

8The “fitness culture” in America continues to grow and shows no signs of slowing down anytime soon. As we become increasingly aware of the health benefits of fitness and as we continue to experience stress in our busy lives, we are bound to have even more need of the community support and the good fun of exercising with others at the local gym.

Works Cited

Active Marketing Group. “2007 Health Club Industry Review.” The Active Network. The Active Network, 2007. Web. 4 Apr. 2012.

Brudzynski, Laura, and William P. Ebben. “Body Image as a Motivator and Barrier to Exercise Participation.” International Journal of Exercise Science 3(1): 14–24, 2010. WKU Top Scholar. Web. 6 Apr. 2012.

Glenn, David J. “Exercise Activities Mellowing Out.” Fairfield County Business Journal 2 June 2003: 22. Regional Business News. Web. 6 Apr. 2012.

Harton, Dorothy. Personal interview. 3 Apr. 2012.

International Health, Racquet & Sportsclub Association. “IHRSA Quarterly Consumer Study Available Free to IHRSA Members.” IHRSA, 29 Nov. 2011. Web. 8 Apr. 2012.

- - - “U.S. Health Club Membership Exceeds 50 Million, Up 10.8%; Industry Revenue Up 4% as New Members Fuel Growth.” IHRSA, 5 April 2011. Web. 5 Apr. 2012.

Larner, Catherine. “Will Gym Fix It for You?” Challenge Newsline 31.1 (2003): 1–2. Academic Search Premier. Web. 6 Apr. 2012.

Leepson, Marc. “Physical Fitness.” CQ Researcher 2.41 (1992): 953–76. CQ Researcher. Web. 9 Apr. 2012.

Pew Research Center. “In the Battle of the Bulge, More Soldiers Than Successes.” Pew Research Center Publications. Pew Research Center, 26 April 2006. Web. 4 Apr. 2012.

“Physical Fitness Trumps Body Weight in Reducing Death Risks, Study Finds.” Science Daily. Science Daily, 5 Dec. 2011. Web. 4 Apr. 2012.

Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Touchstone-Simon and Schuster, 2001. Print.

Sisson, Mary. “Gyms Dandy.” Crain’s New York Business 26 Aug. 2002: 1–2. Regional Business News. Web. 3 Apr. 2012.

Smits, Jasper A. J., and Michael W. Otto. Exercise for Mood and Anxiety. New York: Oxford UP, 2011. Print.

Question

[Answer Question]

Stern, Marc. “The Fitness Movement and the Fitness Center Industry, 1960–2000.” Business and Economic History On-Line 6 (2008): 1–26. Business History Conference. Web. 5 Apr. 2012.