3f Planning

Contents:

Creating an informal plan

Writing a formal outline

Making a storyboard

At this point, you will find it helpful to write out an organizational plan, outline, or storyboard. To do so, simply begin with your thesis; review your exploratory notes, research materials, and visual or multimedia sources; and then list all the examples and other good reasons you have to support the thesis. (For information on paragraph-level organization, see Chapter 5.)

Creating an informal plan

Creating an informal plan

One informal way to organize your ideas is to figure out what belongs in your introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. A student who was writing about solutions to a problem used the following plan:

WORKING THESIS

Increased motorcycle use demands the reorganization of campus parking lots.

INTRODUCTION

give background and overview (motorcycle use up dramatically), and include photograph of overcrowded lot

state purpose—to fulfill promise of thesis by offering solutions

BODY

describe current situation (tell of my research at area parking lots)

describe problem in detail (report on statistics; cars vs. cycles), and graph my findings

present two possible solutions (enlarge lots or reallocate space)

CONCLUSION

recommend against first solution because of cost and space

recommend second solution, and summarize advantages

Writing a formal outline

Writing a formal outline

Even if you have created an informal written plan before drafting, you may wish (or be required) to prepare a more formal outline, which can help you see exactly how the parts of your writing will fit together—how your ideas relate, where you need examples, and what the overall structure of your work will be. Even if your instructor doesn’t ask you to make an outline or you prefer to use some other method of sketching out your plans, you may want to come back to an outline later: doing a retrospective outline—one you do after you’ve already drafted your project—is a great way to see whether you have any big logical gaps or whether parts of the essay are in the wrong place.

Most formal outlines follow a conventional format of numbered and lettered headings and subheadings, using roman numerals, capital letters, arabic numerals, and lowercase letters to show the levels of importance of the various ideas and their relationships. Each new level is indented to show its subordination to the preceding level.

Thesis statement

- First main idea

- First subordinate idea

- First supporting detail or idea

- Second supporting detail or idea

- Third supporting detail

- Second subordinate idea

- First supporting detail or idea

- Second supporting detail or idea

- First subordinate idea

- Second main idea

- (continues as above)

Note that each level contains at least two parts, so there is no A without a B, no 1 without a 2. Comparable items are placed on the same level—the level marked by capital letters, for instance, or arabic numerals. Keep in mind that headings should be stated in parallel form—either all sentences or all grammatically parallel topics.

Formal outlining requires a careful evaluation of your ideas, and this is precisely why it is valuable. (A full-sentence outline will reveal the relationships between ideas—or the lack of relationships—most clearly.) Remember, however, that an outline is at best a means to an end, not an end in itself. Whatever form your plan takes, you may want or need to change it along the way. (For an example of a formal outline, see 15e.)

Making a storyboard

Making a storyboard

The technique of storyboarding—working out a narrative or argument in visual form—can be a good way to come up with an organizational plan, especially if you are developing a video essay, Web site, or other media project. You can find storyboard templates online to help you get started, or you can create your own storyboard by using note cards or sticky notes. Even if you’re writing a more traditional word-based college essay, however, you may find storyboarding helpful; take advantage of different colors to keep track of threads of argument, subtopics, and so on. Flexibility is a strong feature of storyboarding: you can move the cards and notes around, trying out different arrangements, until you find an organization that works well for your writing situation.

Here are some possible organizational patterns for a storyboard.

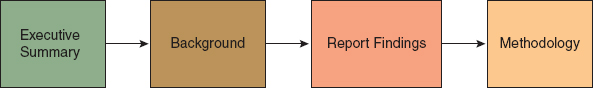

Use linear organization when you want readers to move in a particular order through your material. An online report might use the following linear organization:

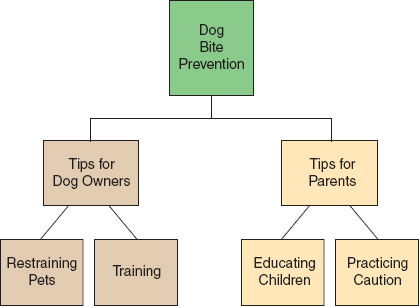

A hierarchy puts the most important material first, with subtopics branching out from the main idea. A Web site on dog bite prevention might be arranged like this:

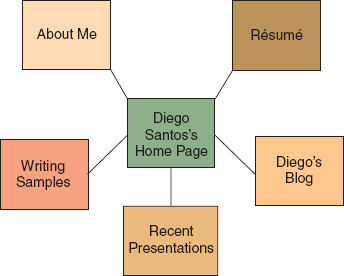

A spoke-and-hub organization allows readers to move from place to place in no particular order. Many portfolio Web sites are arranged this way:

Whatever form your plan takes, you may want or need to change it along the way. Writing has a way of stimulating thought, and the process of drafting may generate new ideas. Or you may find that you need to reexamine some data or information or gather more material.