8d Reading emotional, ethical, and logical appeals

Contents:

Analyzing emotional appeals

Analyzing ethical appeals

Analyzing logical appeals

Analyzing appeals in a visual argument

Tutorial: Reading visuals for audience

Tutorial: Reading visuals for purpose

Aristotle categorized argumentative appeals into three types: emotional appeals that speak to our hearts and values (known to the ancient Greeks as pathos), ethical appeals that appeal to character (ethos), and logical appeals that involve factual information and evidence (logos).

Analyzing emotional appeals

Analyzing emotional appeals

Emotional appeals stir our emotions and remind us of deeply held values. When politicians argue that the country needs more tax relief, they almost always use examples of one or more families they have met, stressing the concrete ways in which a tax cut would improve the quality of their lives. Doing so creates a strong emotional appeal. Some have criticized the use of emotional appeals in argument, claiming that they are a form of manipulation intended to mislead an audience. But emotional appeals are an important part of almost every argument. Critical readers “talk back” to such appeals by analyzing them, deciding which are acceptable and which are not.

The accompanying photo shows gun-rights advocates rallying in Boston. To what emotions are the protesters appealing here? Do you find this appeal effective, manipulative, or both? Would you accept this argument? On what grounds would you do so?

Analyzing ethical appeals

Analyzing ethical appeals

Ethical appeals support the credibility, moral character, and goodwill of the argument’s creator. These appeals are especially important for critical readers to recognize and evaluate. Should a respected baseball manager’s credibility in the clubhouse convince you to invest in mutual funds he promotes? Should an actress respected for her award-winning roles convince you to give to a particular charity? To identify ethical appeals in arguments, ask yourself these questions: What is the creator of the argument doing to show that he or she is knowledgeable and credible about the subject—has really done the homework on it? What sort of character does he or she build, and how? More important, is that character trustworthy? What does the creator of the argument do to show that he or she has the best interests of an audience in mind? Do those best interests match your own, and, if not, how does that alter the effectiveness of the argument? Try to identify the ethical appeals that documentary filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer makes in this excerpt from his “Director’s Statement” for the The Act of Killing, a film in which the perpetrators of massacres in 1960s Indonesia reenact the murders they committed:

When I began developing The Act of Killing in 2005, I had already been filming for three years with survivors of the 1965–66 massacres. I had lived for a year in a village of survivors in the plantation belt outside Medan. I had become very close to several of the families there. During that time, Christine Cynn and I collaborated with a fledgling plantation workers’ union to make The Globalization Tapes, and began production on a forthcoming film about a family of survivors that begins to confront (with tremendous dignity and patience) the killers who murdered their son. Our efforts to record the survivors’ experiences—never before expressed publicly—took place in the shadow of their torturers, as well as the executioners who murdered their relatives—men who, like Anwar Congo, would boast about what they did.

—JOSHUA OPPENHEIMER

Analyzing logical appeals

Analyzing logical appeals

Logical appeals are often viewed as especially trustworthy: “The facts don’t lie,” some say. Of course, facts are not the only type of logical appeals, which also include firsthand evidence drawn from observations, interviews, surveys and questionnaires, experiments, and personal experience; and secondhand evidence drawn from authorities, the testimony of others, statistics, and other print and online sources. Critical readers need to examine logical appeals just as carefully as emotional and ethical ones. What is the source of the logical appeal—and is that source trustworthy? Are all terms defined clearly? Has the logical evidence presented been taken out of context, and, if so, does that change the meaning of the data? Look, for example, at the following brief passage:

[I]t is well for us to remember that, in an age of increasing illiteracy, 60 percent of the world’s illiterates are women. Between 1960 and 1970, the number of illiterate men in the world rose by 8 million, while the number of illiterate women rose by 40 million.1 And the number of illiterate women is increasing.

—ADRIENNE RICH, “What Does a Woman Need to Know?”

As a critical reader, you would question these facts and hence check the footnote to discover the source, which in this case is the UN Compendium of Social Statistics. At this point, you might accept this document as authoritative—or you might look further into the United Nations’ publications policy, especially to find out how that body defines illiteracy. You would also no doubt wonder why Rich chose the decade from 1960 to 1970 for her example and, as a result, check to see when this essay was written. As it turns out, the essay was written in 1979, so the most recent data available on literacy would have come from the decade of the sixties. That fact might make you question the timeliness of these statistics: Are they still meaningful more than forty years later? How might these statistics have changed?

If you attend closely to the emotional, ethical, and logical appeals in any argument, you will be on your way to analyzing—and evaluating—it.

Analyzing appeals in a visual argument

Analyzing appeals in a visual argument

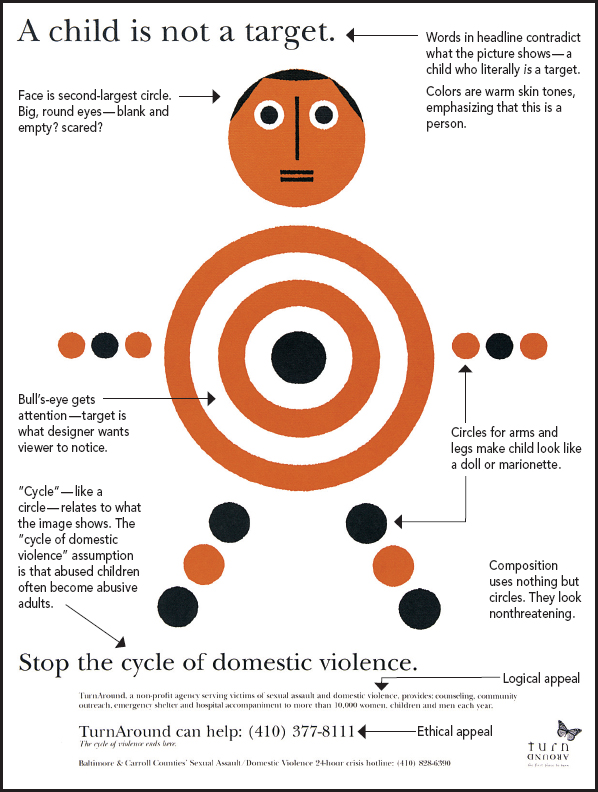

The poster at the bottom of the page, from TurnAround, an organization devoted to helping victims of domestic violence, is “intended to strike a chord with abusers as well as their victims.” The dramatic combination of words and image builds on an analogy between a child and a target and makes strong emotional and ethical appeals.

The bull’s-eye that draws your attention to the center of the poster is probably the first thing you notice when you look at the image. Then you may observe that the “target” is, in fact, a child’s body; it also has arms, legs, and a head with wide, staring eyes. The heading at the upper left, “A child is not a target,” reinforces the bull’s-eye/child connection.

This poster’s stark image and headline appeal to viewers’ emotions, offering the uncomfortable reminder that children are often the victims of domestic violence. The design causes viewers to see a target first and only afterward recognize that the target is actually a child—an unsettling experience. But the poster also offers ethical appeals (“TurnAround can help”) to show that the organization is credible and that it supports the worthwhile goal of ending “the cycle of domestic violence” by offering counseling and other support services. Finally, it uses the logical appeal of a statistic to support this ethical appeal, noting that TurnAround has served “more than 10,000 women, children and men each year” and giving specific information about where to get help.

For Multilingual Writers: Recognizing appeals in various settings