32a Understanding the basics of MLA style

Contents:

Context of your sources

Parts of citations

Explanatory notes

Why does academic work call for very careful citation practices when writing for the general public may not? The answer is that readers of your academic work expect source citations for several reasons:

- Source citations demonstrate that you’ve done your homework on your topic and that you are a part of the conversation surrounding it. Careful citation shows your readers what you know, where you stand, and what you think is important.

- Source citations show your readers that you understand the need to give credit when you make use of someone else’s intellectual property. Especially in academic writing, when it’s better to be safe than sorry, include a citation for any source you think you might need to cite. (See 14b.)

- Source citations give explicit directions to guide readers who want to look for themselves at the works you’re using.

The guidelines for MLA style help you with this last purpose, giving you instructions on exactly what information to include in your citation and how to format that information.

Context of your sources

Context of your sources

New kinds of sources crop up regularly, and each new medium once required new guidelines from MLA. But the MLA Handbook, 8th Edition, provides advice writers can use to cite any kind of source. There are often several “correct” ways to cite a source, so you will need to think carefully about your own context for using the source so you can identify the pieces of information that you should emphasize or include and any other information that might be helpful to your readers.

Elements of MLA citations

The first step is to identify elements that are commonly found in most works writers cite.

AUTHOR AND TITLE

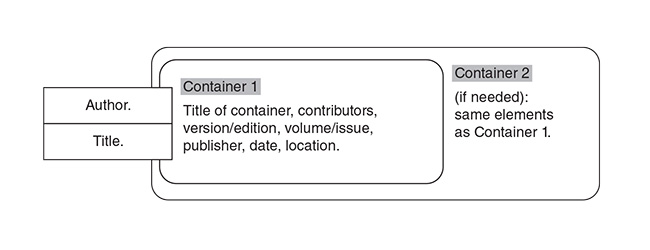

The first two elements, both of which are needed for many sources, are the author’s name and the title of the work. Each of these elements is followed by a period.

Author.

Title.

Even in these elements, your context is important. The author of a novel may be obvious, but who is the “author” of a television episode? The director? The writer? The show’s creator? The star? The answer may depend on the focus of your own work. If an actor’s performance is central to your discussion, then MLA guidelines ask you to identify the actor as the author. If the plot is your focus, you might name the writer of the episode as the author.

CONTAINER

The next step is to identify elements of what the MLA calls the “container” for the work. The context in which you are discussing the source and the context in which you find the source will help you determine what counts as a container—and whether you need a container other than the title—in each case. A standalone source, such as a print novel, won’t require you to name a separate container. If you watch a movie in a theater, you won’t identify a container. But if you watch the same movie as part of a DVD box set of the director’s work, the container title is the name of the box set. If you read an article in a print journal, the first container is the journal the article appears in. If you read it online, the journal may also be part of a second, larger container, such as a database. Thinking about a source as nested in larger containers may help you to visualize how a citation works.

The elements you may include in the “container” part of your citation include the title of the larger container; the names of contributors such as editors or translators; the version or edition; the volume and issue numbers; the publisher or sponsor; the date of publication; and a location such as the page numbers, URL, or DOI. These elements are separated by commas, and the end of the container is marked with a period.

Most sources won’t include all these pieces of information, so include only the elements that are available and relevant to create an acceptable citation. If you need a second container, you simply add it after the first one. In the following sections, you will find many examples of how elements and containers are combined to create citations within your project and at the end.

Examples from student work

ARTICLE IN A DATABASE

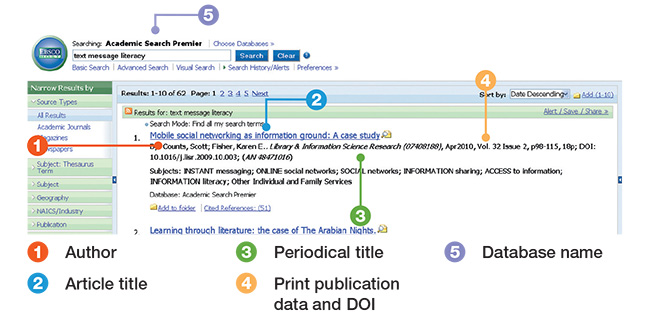

David Craig found a potentially useful article in Academic Search Premier, a database he accessed through his library website. Many databases are digital collections of articles that originally appeared in print periodicals, and the articles usually have the same written-word content as they did in print form, without changes or updates. Database sources have usually been carefully reviewed before publication, either by an editor, an editorial board, or peer reviewers. While finding information in an article from a database is not a surefire guarantee of credibility, such information is often more authoritative than much of what you find for free on the web.

From the page shown below, David Craig was able to click through to read the full text of the article. He printed this computer screen in case he needed to cite the article: the image has all the information that he would need to create a complete MLA citation, including the original print publication information for the article, the name of the database, and the location (here, a “digital object identifier” or DOI, which provides the source’s permanent location).

A SOURCE FROM A DATABASE

A complete citation for this article would look like this:

Counts, Scott, and Karen E. Fisher. “Mobile Social Networking as Information Ground: A Case Study.” Library and Information Science Research, vol. 32, no. 2, Apr. 2010, pp. 98-115. Academic Search Premier, doi:10.1016/j .lisr.2009.10.003.

Note that the periodical, Library and Information Science Research, is the first “container” of the article, and the database, Academic Search Premier, is the second “container.” Notice, too, that the first container includes just four relevant elements—the journal title, number (here, that means the volume and issue numbers), date, and page numbers; and the second container includes just two—the database title and location. Publisher information is not required for journals and databases.

OTHER KINDS OF SOURCES

While researching her presentation on Alison Bechdel’s graphic memoir Fun Home, Shuqiao Song came across a brief video interview with Bechdel on YouTube that she wanted to play for her audience. However, the YouTube post noted that the interview had originally appeared on a web series called Stuck in Vermont. At first Shuqiao was puzzled: should she be citing a video, an interview, a work from a website, or something else? She used the information available on YouTube and followed the “container” template, naming Bechdel (who is speaking in the video clip) as the author, with the interviewer identified after the title of the piece.

Bechdel, Alison. “Stuck in Vermont 109: Alison Bechdel.” Interview by Eva Sollberger. YouTube, 13 Dec. 2008, www.youtube.com/watch?v=nWBFYTmpC54.

Parts of citations

Parts of citations

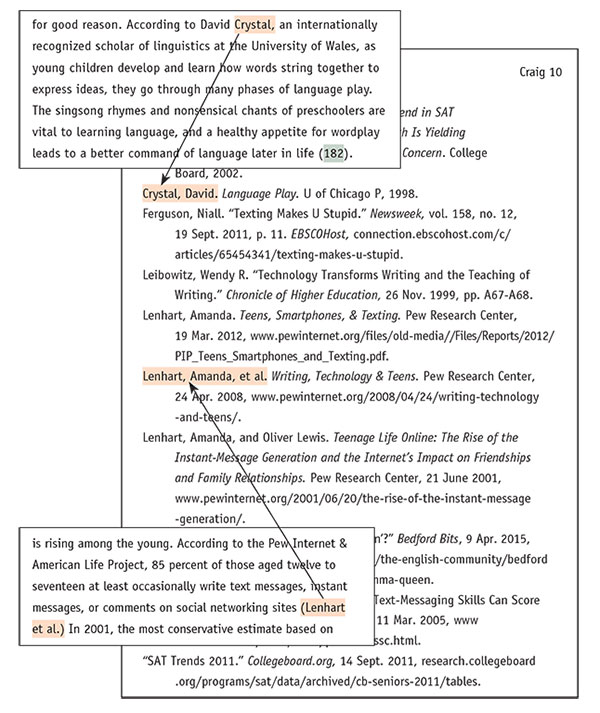

MLA citations appear in two parts—a brief in-text citation in parentheses in the body of your written text, and a full citation in the list of works cited, to which the in-text citation directs readers. A basic in-text citation includes the author’s name and the page number (for a print source), but many variations on this format are discussed in 32c.

In the text of his research project—see 32e—David Craig paraphrases material from the print book Language Play by linguist David Crystal. As shown below, he cites the book page on which the original information appears in a parenthetical reference that points readers to the entry for “Crystal, David” in his list of works cited. He also cites statistics from a report that he found on a website sponsored by the nonprofit Pew Internet and American Life Project. The report, like many online texts, does not include page numbers. These examples show just two of the many ways to cite sources using in-text citations and a list of works cited. You’ll need to make case-by-case decisions based on the types of sources you include.

Explanatory notes

Explanatory notes

MLA citation style asks you to include explanatory notes for information that doesn’t readily fit into your text but is needed for clarification or further explanation. In addition, MLA permits bibliographic notes to give information about or evaluate a source, or to list multiple sources that relate to a single point. Use superscript numbers in the text to refer readers to the notes, which may appear as endnotes (under the heading Notes on a separate page immediately before the list of works cited) or as footnotes at the bottom of each page where a superscript number appears.

EXAMPLE OF SUPERSCRIPT NUMBER IN TEXT

Although messaging relies on the written word, many messagers disregard standard writing conventions. For example, here is a snippet from an IM conversation between two teenage girls:1

EXAMPLE OF EXPLANATORY NOTE

1. This transcript of an IM conversation was collected on 20 Nov. 2012. The teenagers’ names are concealed to protect their privacy.