42d Comparatives and superlatives

Contents:

Using irregular forms

Choosing comparatives or superlatives

Considering double comparatives and superlatives

Considering incomplete comparisons

Considering absolute concepts

Considering multiple negatives

Most adjectives and adverbs have three forms: positive, comparative, and superlative.

| POSITIVE | COMPARATIVE | SUPERLATIVE |

| large | larger | largest |

| early | earlier | earliest |

| careful | more careful | most careful |

| delicious | more delicious | most delicious |

Canada is larger than the United States.

My son needs to be more careful with his money.

This is the most delicious coffee we have tried.

The comparative and superlative of most short (one-syllable and some two-syllable) adjectives are formed by adding -er and -est. With some two-syllable adjectives, longer adjectives, and most adverbs, use more and most: scientific, more scientific, most scientific; elegantly, more elegantly, most elegantly. If you are not sure whether a word has -er and -est forms, consult the dictionary entry for the simple form.

Using irregular forms

Using irregular forms

A number of adjectives and adverbs have irregular comparative and superlative forms.

| POSITIVE | COMPARATIVE | SUPERLATIVE |

| good, well | better | best |

| bad, badly, ill | worse | worst |

| little (quantity) | less | least |

| many, some, much | more | most |

Choosing comparatives or superlatives

Choosing comparatives or superlatives

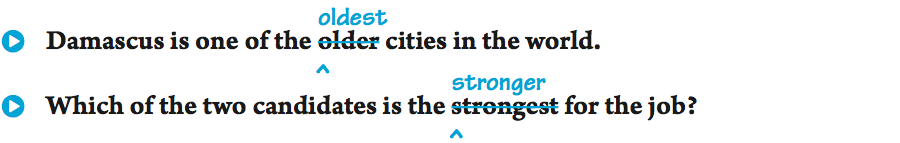

In academic writing, use the comparative to compare two things; use the superlative to compare three or more.

Rome is a much older city than New York.

Considering double comparatives and superlatives

Considering double comparatives and superlatives

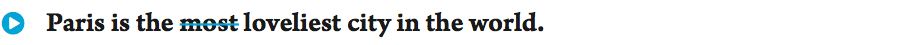

Double comparatives and superlatives, used in some informal contexts, use both more or most and the -er or -est ending. Occasionally they can act to build a special emphasis, as in the title of Spike Lee’s movie Mo’ Better Blues. In college writing, however, double comparatives and superlatives may count against you. Make sure not to use more or most before adjectives or adverbs ending in -er or -est in formal situations.

Considering incomplete comparisons

Considering incomplete comparisons

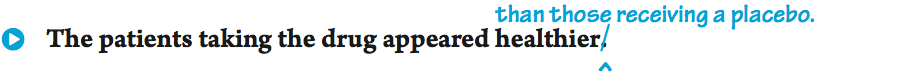

Even if you think your audience will understand an implied comparison, you will be safer if you make sure that comparisons in formal writing are complete and clear (49e).

Considering absolute concepts

Considering absolute concepts

Some readers consider modifiers such as perfect and unique to be absolute concepts; according to this view, a construction such as more unique is illogical because a thing is either unique or it isn’t, so modified forms of the concept don’t make sense. However, many seemingly absolute words have multiple meanings, all of which are widely accepted as correct. For example, unique may mean one of a kind or unequaled, but it can also simply mean distinctive or unusual.

If you think your readers will object to a construction such as more perfect (which appears in the U.S. Constitution) or somewhat unique, then avoid such uses.

Considering multiple negatives

Considering multiple negatives

One common type of repetition is to use more than one negative term in a negative statement. In I can’t hardly see you, for example, both can’t and hardly carry negative meanings. Emphatic double negatives—and triple, quadruple, and more—are especially common in the South and among speakers of some African American varieties of English, who may say, for example, Don’t none of my people come from up North.

Multiple negatives have a long history in English (and in other languages) and can be found in the works of Chaucer and Shakespeare. In the eighteenth century, however, in an effort to make English more logical, double negatives came to be labeled as incorrect. In college writing, you may well have reason to quote passages that include them (whether from Shakespeare, Toni Morrison, or your grandmother), but it is safer to avoid other uses of double negatives in academic writing.