The Top Twenty: A Quick Guide to Troubleshooting Your Writing

THE TOP TWENTY

THE TOP TWENTYContents:

Directory: The Top Twenty

Quick Help: Taking a writing inventory

Top Twenty Editing Quiz 1: "Thinking Globally by Eating Locally"

Top Twenty Editing Quiz 2: "Plagiarism in the Age of the Internet"

ALTHOUGH MANY PEOPLE THINK of correctness as absolute, based on unchanging rules, instructors and students know that there are rules, but they change with time. “Is it okay to use I in essays for this class?” asks one student. “My high school teacher wouldn’t let us.” In the past, use of first person was discouraged by instructors, sometimes even banned. But today, most fields accept such usage in moderation. Such examples show that rules clearly exist but that they are always shifting and that they thus need our ongoing attention.

The conventions involving surface errors—grammar, punctuation, word choice, and other small-scale matters—are a case in point. Surface errors don’t always disturb readers. Whether your instructor marks an error in any particular assignment will depend on his or her judgment about how serious and distracting it is and what you should be giving priority to at the time. In addition, not all surface errors are consistently viewed as errors: some of the patterns identified in the research for this book are considered errors by some instructors but as stylistic options by others.

Shifting standards do not mean that there is no such thing as correctness in writing—only that correctness always depends on some context. Correctness is not so much a question of absolute right or wrong as of the way the choices a writer makes are perceived by readers. As writers, we all want to be considered competent and careful. We know that our readers judge us by our control of the conventions we have agreed to use, even if the conventions change from time to time.

To help you in producing writing that is conventionally correct, you should become familiar with the twenty most common error patterns among U.S. college students today, listed on the next page in order of frequency. These twenty errors are the ones most likely to result in negative responses from your instructors and other readers. A brief explanation and examples of each error are provided in the following sections, and each error pattern is cross-referenced to other places in this book where you can find more detailed information and additional examples.

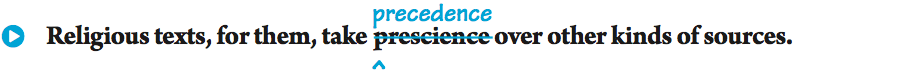

1Wrong word

Prescience means “foresight,” and precedence means “priority of importance.”

Allegory, which refers to a symbolic meaning, is a spell checker’s replacement for a misspelling of allergy.

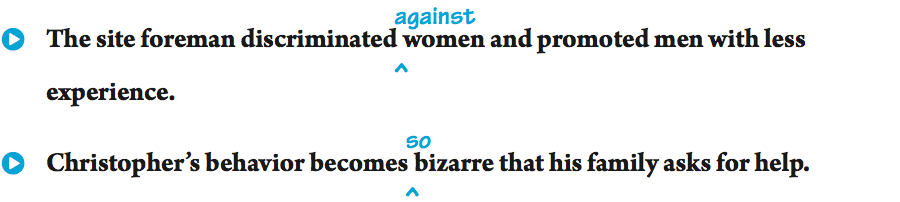

Wrong-word errors can involve using a word with the wrong shade of meaning, a word with a completely wrong meaning, or a wrong preposition or word in an idiom. Selecting a word from a thesaurus without being certain of its meaning or allowing a spell checker to correct your spelling automatically can lead to wrong-word errors, so use these tools with care. If you have trouble with prepositions and idioms, memorize the standard usage. (See Chapter 30 on choosing the correct word, 31f on using spell checkers wisely, and Chapter 43 on using prepositions and idioms.)

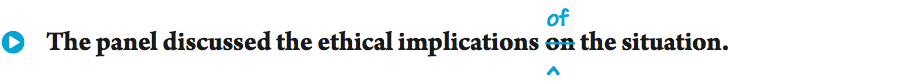

2Missing comma after an introductory element

Readers usually need a small pause between an introductory word, phrase, or clause and the main part of the sentence, a pause most often signaled by a comma. Try to get into the habit of using a comma after every introductory element. When the introductory element is very short, you don’t always need a comma after it. But you’re never wrong if you do use a comma. (See 54a.)

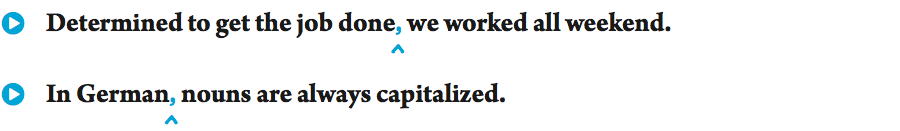

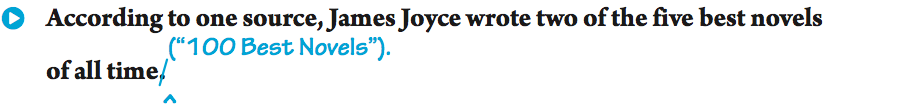

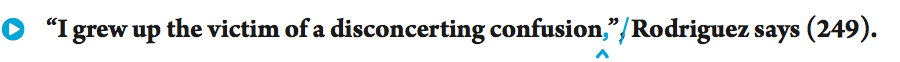

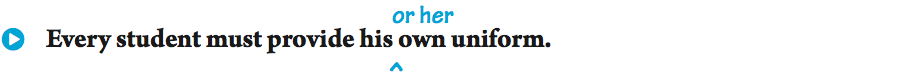

3Incomplete or missing documentation

The writer is citing a print source using MLA style and needs to include the page number where the quotation appears.

The writer must identify the source. Because “100 Best Novels” is an online source, no page number is needed.

Be sure to cite each source as you refer to it in the text, and carefully follow the guidelines of the documentation style you are using to include all the information required (see Chapters 32–35). Omitting documentation can result in charges of plagiarism (see Chapter 14).

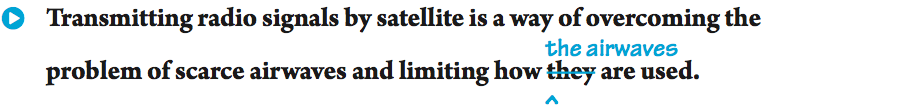

4Vague pronoun reference

POSSIBLE REFERENCE TO MORE THAN ONE WORD

Does they refer to the signals or the airwaves? The editing clarifies what is being limited.

REFERENCE IMPLIED BUT NOT STATED

What does which refer to? The editing clarifies what employees resented.

A pronoun—a word such as she, yourself, her, it, this, who, or which—should refer clearly to the word or words it replaces (called the antecedent) elsewhere in the sentence or in a previous sentence. If more than one word could be the antecedent, or if no specific antecedent is present in the sentence, edit to make the meaning clear. (See 41h.)

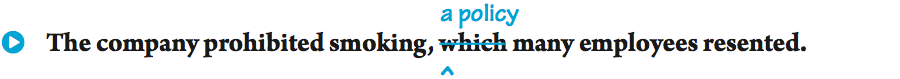

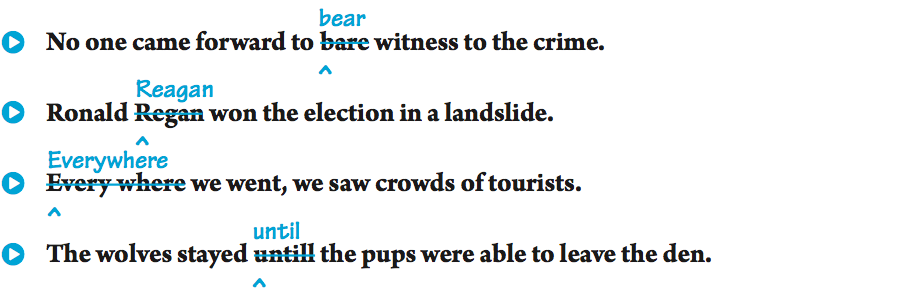

5Spelling (including homonyms)

The most common kinds of misspellings today are those that spell checkers cannot identify. The categories that spell checkers are most likely to miss include homonyms (words that sound alike but have different meanings); compound words incorrectly spelled as two separate words; and proper nouns, particularly names. Proofread carefully for errors that a spell checker cannot catch—and be sure to run the spell checker to catch other kinds of spelling mistakes. (See 31f.)

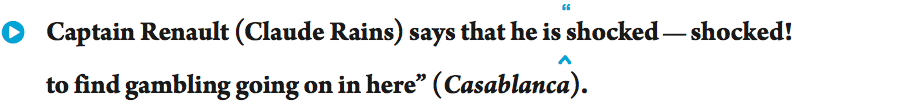

6Mechanical error with a quotation

The comma should be placed inside the quotation marks.

Both the beginning and the end of the quotation (from the film Casablanca) should be marked with quotation marks.

Follow conventions when using quotation marks with commas (54i), semicolons (55c), question marks (56b), and other punctuation (58e). Always use quotation marks in pairs, and follow the guidelines of your documentation style for block quotations and poetry (58a). Use quotation marks to mark titles of short works (58b), but use italics for titles of long works (62a).

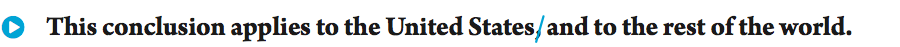

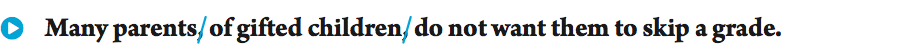

7Unnecessary comma

BEFORE CONJUNCTIONS IN COMPOUND CONSTRUCTIONS THAT ARE NOT COMPOUND SENTENCES

No comma is needed before and because it is joining two phrases that modify the same verb, applies.

WITH RESTRICTIVE ELEMENTS

No comma is needed to set off the restrictive phrase of gifted children; it is necessary to indicate which parents the sentence is talking about.

Do not use commas to set off restrictive elements—those necessary to the meaning of the words they modify. Do not use a comma before a coordinating conjunction (and, but, for, nor, or, so, yet) when the conjunction is not joining two parts of a compound sentence. Do not use a comma before the first or after the last item in a series, and do not use a comma between a subject and verb, between a verb and its object or complement, or between a preposition and its object. (See 54k.)

8Unnecessary or missing capitalization

Capitalize proper nouns and proper adjectives, the first words of sentences, and important words in titles, along with certain words indicating directions and family relationships. Do not capitalize most other words, and proofread to make sure your word processor has not automatically added unnecessary capitalization (after an abbreviation ending with a period, for example). When in doubt, check a dictionary. (See Chapter 60.)

9Missing word

Be careful not to omit little words, including prepositions (43a), parts of two-part verbs (43b), and correlative conjunctions (36g). Proofread carefully for any other omitted words, and be particularly careful not to omit words from quotations.

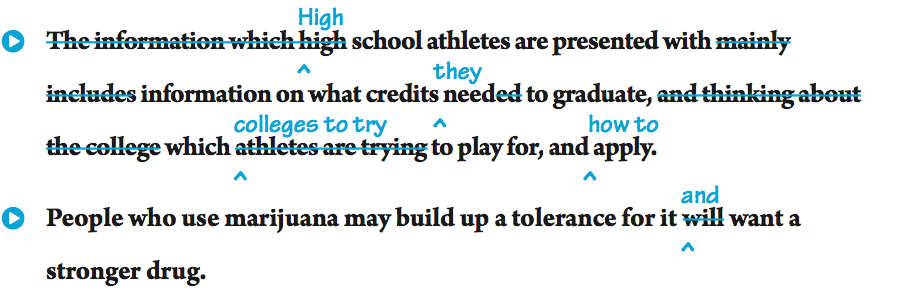

10Faulty sentence structure

When a sentence starts out with one kind of structure and then changes to another kind, it confuses readers. If readers have trouble following the meaning of your sentence, read the sentence aloud and make sure that it contains a subject and a verb (37a and b). Look for mixed structures (49a), subjects and predicates that do not make sense together (49b), and comparisons with unclear meanings (49e). When you join elements (such as subjects or verb phrases) with a coordinating conjunction—and, but, for, nor, or, so, or yet—make sure that the elements have parallel structures (45b).

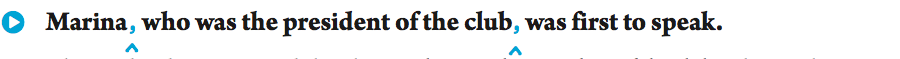

11Missing comma with a nonrestrictive element

The reader does not need the clause who was the president of the club to know the basic meaning of the sentence: Marina was first to speak.

A nonrestrictive element is not essential to the basic meaning of a sentence. If you remove a nonrestrictive element, the sentence would still make sense. Use commas to set off any nonrestrictive elements from the rest of a sentence. (See 54d.)

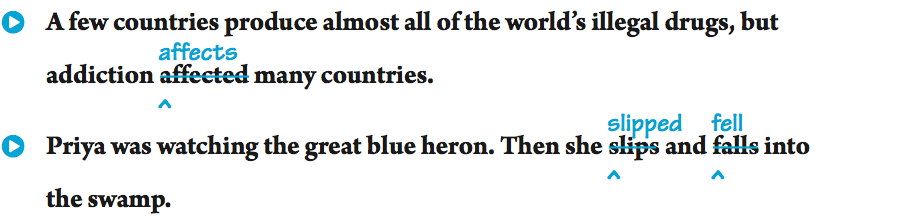

12Unnecessary shift in verb tense

Verb tenses tell readers when actions take place: saying Ron went to school indicates a past action whereas saying he will go indicates a future action. Verbs that shift from one tense to another with no clear reason can confuse readers. (See 44a.)

13Missing comma in a compound sentence

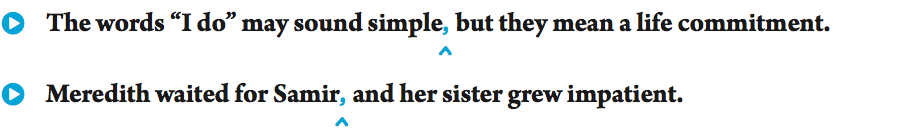

Without the comma, a reader may think at first that Meredith waited for Samir and her sister.

A compound sentence consists of two or more parts that could each stand alone as a sentence. When the parts are joined by a coordinating conjunction—and, but, so, yet, or, nor, or for—use a comma before the conjunction to indicate a pause between the two thoughts. In very short sentences, the comma is optional if the sentence can be easily understood without it. Including the comma, however, will never be wrong. (See 54c.)

14Unnecessary or missing apostrophe (including its / it’s)

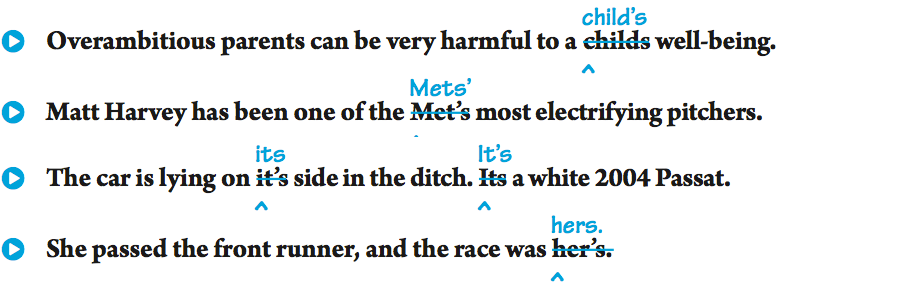

To make a noun possessive, add either an apostrophe and an -s (Ed’s book) or an apostrophe alone (the boys’ gym). Do not use an apostrophe with the possessive pronouns ours, yours, hers, its, and theirs. Use its to mean belonging to it; use it’s only when you mean it is or it has. (See Chapter 57.)

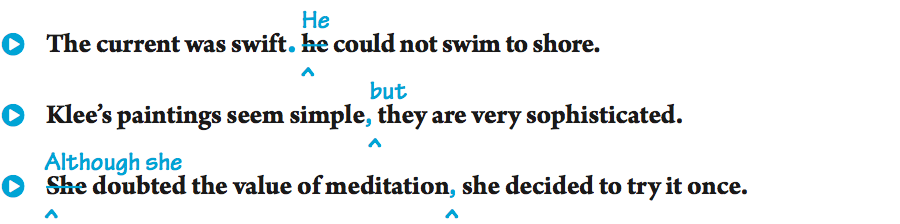

15Fused (run-on) sentence

A fused sentence (also called a run-on sentence) is created when clauses that could each stand alone as a sentence are joined with no punctuation or words to link them. Fused sentences must either be divided into separate sentences or joined by adding words, punctuation, or both. (See Chapter 46.)

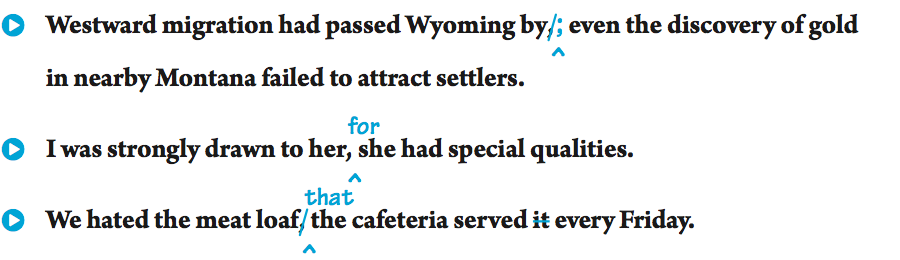

16Comma splice

A comma splice occurs when only a comma separates clauses that could each stand alone as a sentence. To correct a comma splice, you can insert a semicolon or period, connect the clauses clearly with a word such as and or because, or restructure the sentence. (See Chapter 46.)

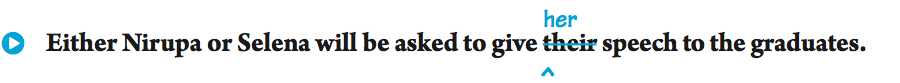

17Lack of pronoun-antecedent agreement

Many indefinite pronouns, such as everyone and each, are always singular.

When antecedents are joined by or or nor, the pronoun must agree with the closer antecedent.

A collective noun can be either singular or plural, depending on whether the people are seen as a single unit or as multiple individuals.

With a singular antecedent that can refer to either a man or a woman, you can use his or her, he or she, and so on. You can also rewrite the sentence to make the antecedent and pronoun plural or to eliminate the pronoun altogether.

Pronouns must agree with their antecedents in gender (for example, using he or him to replace Abraham Lincoln and she or her to replace Queen Elizabeth) and in number. (See 41f.)

18Poorly integrated quotation

Quotations should fit smoothly into the surrounding sentence structure. They should be linked clearly to the writing around them (usually with a signal phrase) rather than dropped abruptly into the writing. (See 13b.)

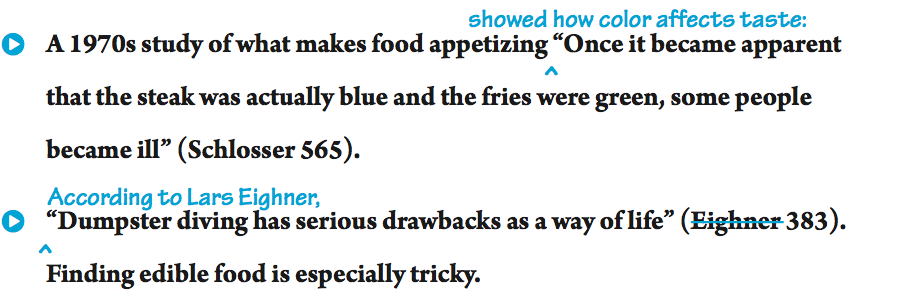

19Unnecessary or missing hyphen

A compound adjective modifying a following noun may require a hyphen.

A complement that follows the noun it modifies should not be hyphenated.

A two-word verb should not be hyphenated.

A compound adjective that appears before a noun often needs a hyphen (63a). However, be careful not to hyphenate two-word verbs or word groups that serve as subject complements (63c).

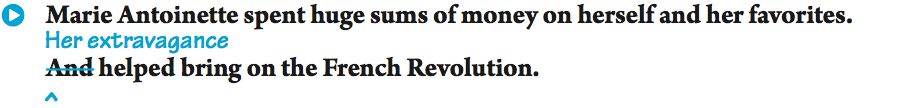

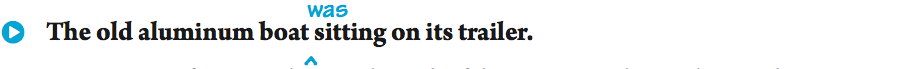

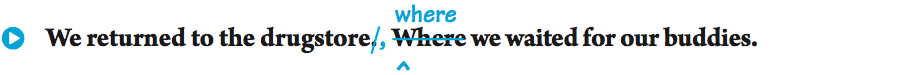

20Sentence fragment

NO SUBJECT

NO COMPLETE VERB

Sitting cannot function alone as the verb of the sentence. The auxiliary verb was makes it a complete verb.

BEGINNING WITH A SUBORDINATING WORD

A sentence fragment is part of a sentence that is written and punctuated as if it were a complete sentence. A fragment may lack a subject, a complete verb, or both. Fragments may also begin with a subordinating word (such as because) that makes the fragment depend on another sentence for its meaning. Reading your draft out loud, backwards, sentence by sentence, will help you spot sentence fragments easily. (See Chapter 47.)