Public Speaking as a Form of Communication

Public speaking is one of four categories of human communication: dyadic, small group, mass, and public speaking. Dyadic communication happens between two people, as in a conversation. Small group communication involves a small number of people who can see and speak directly with one another. Mass communication occurs between a speaker and a large audience of unknown people who are usually not present with the speaker, or who are part of such an immense crowd that there can be little or no interaction between speaker and listener. Mass public rallies and television and radio news broadcasts are examples of mass communication.

In public speaking, a speaker delivers a message with a specific purpose to an audience of people who are present during the delivery of the speech. Public speaking always includes a speaker who has a reason for speaking, an audience that gives the speaker its attention, and a message that is meant to accomplish a specific purpose. Public speakers address audiences largely without interruption and take responsibility for the words and ideas being expressed.

Public Speaking as an Interactive Communication Process

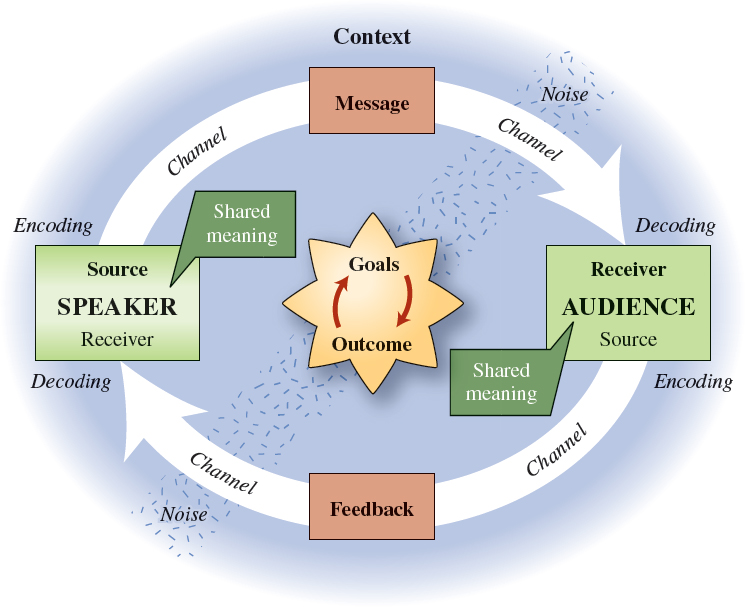

In any communication event, including public speaking, several elements are present and interact with one another. These include the source, the receiver, the message, the channel, and shared meaning (see Figure 1.1).12

The source, or sender, is the person who creates a message. Creating, organizing, and producing the message is called encoding—the process of converting thoughts into words.

The recipient of the source’s message is the receiver, or audience. The process of interpreting the message is called decoding. Audience members decode the meaning of the message selectively, based on their own experiences and attitudes. Feedback, the audience’s response to a message, can be conveyed both verbally and nonverbally.

The message is the content of the communication process: thoughts and ideas put into meaningful expressions, expressed verbally and nonverbally.

The medium through which the speaker sends a message is the channel. If a speaker delivers a message in front of a live audience, the channel is the air through which sound waves travel. Other channels include telephones, televisions, computers, written communication, and of course the ubiquitous Internet.

Noise is any interference with the message. Noise can disrupt the communication process through physical sounds such as cell phones ringing and people talking, through psychological distractions such as heated emotions, or through environmental interference such as a frigid room or the presence of unexpected people.

Shared meaning is the mutual understanding of a message between speaker and audience. The lowest level of shared meaning exists when the speaker has merely caught the audience’s attention. As the message develops, a higher degree of shared meaning is possible. Thus listener and speaker together truly make a speech a speech—they “co-create” its meaning.

Two other factors are critical to consider when preparing and delivering a speech—context and goals. Context includes anything that influences the speaker, the audience, the occasion—and thus, ultimately, the speech. In classroom speeches, context would include (among other things) recent events on campus or in the outside world, the physical setting, the order and timing of speeches, and the cultural orientations of audience members. Successful communication can never be divorced from the concerns and expectations of others.

Part of the context of any speech is the situation that created the need for it in the first place. All speeches are delivered in response to a specific rhetorical situation, or a circumstance calling for a public response. Bearing the rhetorical situation in mind ensures that you maintain an audience-centered perspective—that is, that you keep the needs, values, and attitudes of your listeners firmly in focus.

A clearly defined speech purpose or goal—what you want the audience to learn or do as a result of the speech—is a final prerequisite for an effective speech. Establishing a speech purpose early on will help you proceed through speech preparation and delivery with a clear focus in mind.

Similarities and Differences between Public Speaking and Other Forms of Communication

Public speaking shares both similarities and differences with other forms of communication. Like small group communication, public speaking requires that you address a group of people who are focused on you and expect you to clearly discuss issues that are relevant to the topic and to the occasion. As in mass communication, public speaking requires that you understand and appeal to the audience members’ interests, attitudes, and values. And like dyadic communication, or conversation, public speaking requires that you attempt to make yourself understood, involve and respond to your conversational partners, and take responsibility for what you say.

A key feature of any type of communication is sensitivity to the listeners. Whether you are talking to one person in a coffee shop or giving a speech to a hundred people, your listeners want to feel that you care about their interests, desires, and goals. Skilled conversationalists do this, and so do successful public speakers. Similarly, skilled conversationalists are in command of their material and present it in a way that is organized and easy to follow, believable, relevant, and interesting. Public speaking is no different. Moreover, the audience will expect you to be knowledgeable and unbiased about your topic and to express your ideas clearly.

Although public speaking shares many characteristics of other types of communication, several factors distinguish public speaking from other forms of communication. These include: (1) opportunities for feedback, (2) level of preparation, and (3) degree of formality.

Public speaking presents different opportunities for feedback, or listener response to a message, than does dyadic, small group, or mass communication. Opportunities for feedback are abundant both in conversation and in small group interactions. Partners in conversation continually respond to one another in back-and-forth fashion; in small groups, participants expect interruptions for purposes of clarification or redirection. However, because the receiver of the message in mass communication is physically removed from the messenger, feedback is delayed until after the event, as in TV ratings.

Public speaking offers a middle ground between low and high levels of feedback. Public speaking does not permit the constant exchange of information between listener and speaker that happens in conversation, but audiences can and do provide ample verbal and nonverbal cues to what they are thinking and feeling. Facial expressions, vocalizations (including laughter or disapproving noises), gestures, applause, and a range of body movements all signal the audience’s response to the speaker. The perceptive speaker reads these cues and tries to adjust his or her remarks accordingly. Feedback is more restricted in public speaking situations than in dyadic and small group communication, and preparation must be more careful and extensive. In dyadic and small group communication, you can always shift the burden to your conversational partner or to other group members. Public speaking offers no such shelter, and lack of preparation stands out starkly.

Public speaking also differs from other forms of communication in terms of its degree of formality. In general, speeches tend to occur in more formal settings than do other forms of communication. Formal gatherings such as graduations lend themselves to speeches; they provide a focus and give form—a “voice”—to the event. In contrast, with the exception of formal interviews, dyadic communication (or conversation) is largely informal. Small group communication also tends to be less formal than public speaking, even in business meetings.

Thus public speaking shares many features of everyday conversation, but because the speaker is the focal point of attention in what is usually a formal setting, listeners expect a more systematic presentation than they do in conversation or small group communication. As such, public speaking requires more preparation and practice than the other forms of communication.