Objects

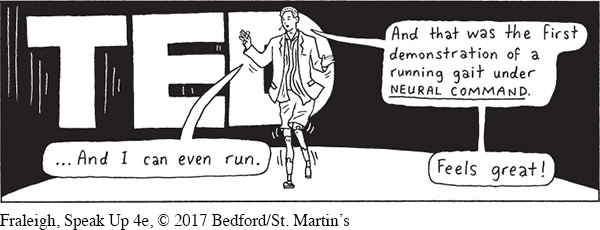

Any object can be a visual aid. For example, in a speech about James Bond movies, one student presented a collection of posters depicting all the actors who ever played 007, from Sean Connery to Daniel Craig. By contrast, in a 2014 TED (Technology, Entertainment, and Design) talk, Hugh Herr introduced a new generation of bionic limbs. Herr, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and director of the biomechatronics research group at the MIT Media Lab, had lost both legs in a climbing accident three decades earlier. In this speech, he described the science behind the new bionic limbs, including mechanical interface (how bionic limbs attach to the physical body), dynamic interface (how bionic limbs move like flesh and bone), and electrical interface (how bionic limbs connect to the central nervous system). As he described each point, he also wore and modeled the bionic limbs—

408

Herr also brought onstage Adrianne Haslet-

Herr spoke to a large audience, and for this reason he used a large projection screen behind him to make the components of a bionic limb accessible to all. If you are using a small object as a presentation aid in a speech to your classmates, consider walking closer to them and holding up the object for them to see.

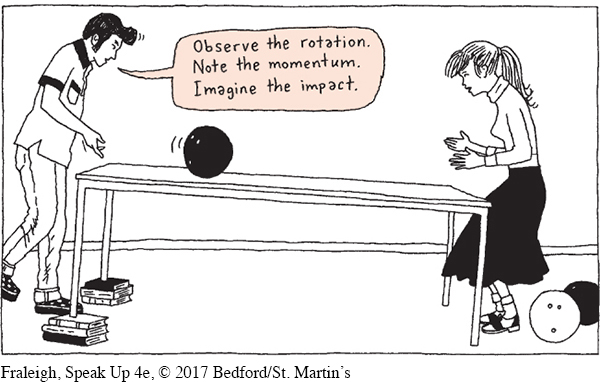

What if you have the opposite challenge: your object is too large or unwieldy to present in its entirety to your audience? This situation calls for equally creative problem solving. Consider Alan, a student who gave a speech about the “physics of bowling.” He explained everything about bowling—

409