Adapting to Audience Disposition

Your listeners’ disposition—

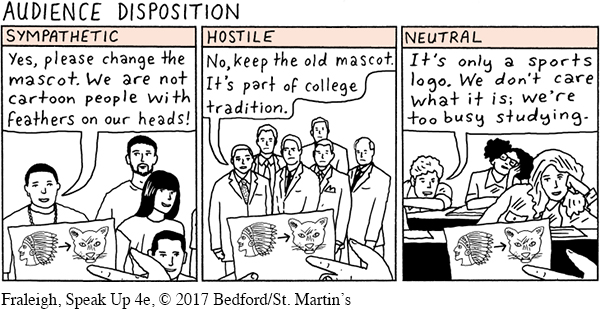

The starting point is to determine where your audience stands on the issue. For example, suppose your goal is to change your college’s mascot from the one that was selected by the school’s founders a century ago to an animal that lives in the wild near your school. You might have the chance to advocate for your idea before several different audiences:

Student groups that believe that the current mascot is disrespectful of their heritage and are looking for a new one

Organizations on campus that support the traditional mascot or are concerned about the cost of making a change

A group of students who are not interested in college sports and are worried about other issues in their lives

Although you want to advocate in favor of changing the mascot with each of these audiences, you wouldn’t use the same supporting arguments with each. Groups on campus that oppose the current mascot would be sympathetic toward your proposal. Organizations that back the current mascot (or do not believe the cost would be affordable) would be hostile to your plan. Finally, busy students who have little interest in college sports may not care about getting involved in your campaign.

513

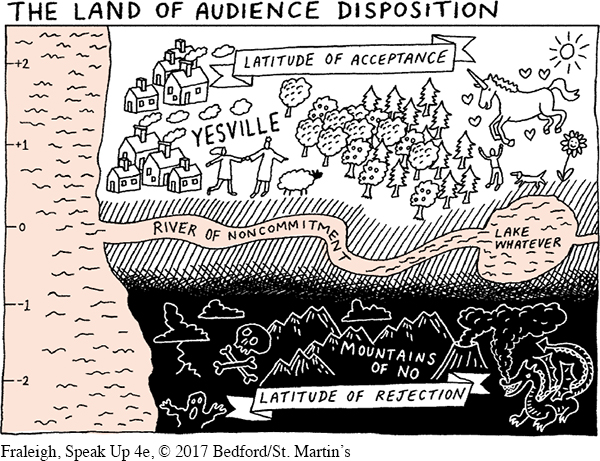

After you know where your audience stands, you can tailor your thesis appropriately. Social judgment theory explains that audience members make a decision about your thesis by comparing it with their own perspectives on the issue. Listeners have a latitude of acceptance, which is the range of positions on a given issue that are acceptable to them. Likewise, they also have a range of positions that are unacceptable, constituting their latitude of rejection.9 Listeners who are very concerned about your issue tend to have a narrower latitude of acceptance. If the issue is not important to them, they will be open to a broader range of positions.10

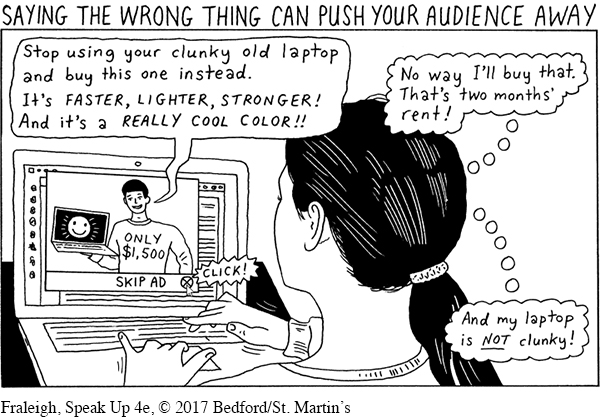

Therefore, you’re most likely to persuade your listeners to change their minds if the position you take on your topic falls within their latitude of acceptance. Conversely, you probably won’t persuade audience members if your position falls within their latitude of rejection—

How does all of this work in practice? Let’s return to the example of your effort to change the school’s mascot. If you are addressing student groups that support the change, their latitude of acceptance may include support for your idea and a desire to take an active role. Such audience members might be willing to attend meetings with college officials, pass out pamphlets on campus, or help make a YouTube video featuring the proposed new mascot.

514

If you are addressing a group that supports the current mascot (a hostile audience), however, a speech calling for a new mascot is likely to be counterproductive because it falls within their latitude of rejection. Your audience analysis might reveal that these listeners would be open to talking to groups on campus that object to the current mascot and learning about their concerns or to making the change slowly over a few years so it would be more affordable. If so, you could advocate one of these options.

Finally, you would take still another approach for the students who are not interested in sports (a neutral audience). Asking them to sign a petition or vote in an election to change the mascot could fall within their latitude of acceptance. However, if you ask them to take a greater role in your campaign, this greater demand on their time might fall within their latitude of rejection.

515