Introduction to Chapter 5

Look for the  and

and  throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.

throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.

“Let the audience drive your message.”

Helena and Matt were newlyweds, fresh out of college, who decided to become organic farmers. After searching for land they could use, they were fortunate to find an agriculture park on rural land owned by the water district for a nearby city. For two years, they farmed their acres, growing some eighty different types of organic vegetables and fruit. They sold their produce to restaurants and farmers’ markets and also to low-income families in a small town near their farm. One day they learned that the water district had decided to expand a parking lot for its workers on land next to the ag park. It would wipe out most of Helena and Matt’s farmland and would threaten other farmers’ land as well.

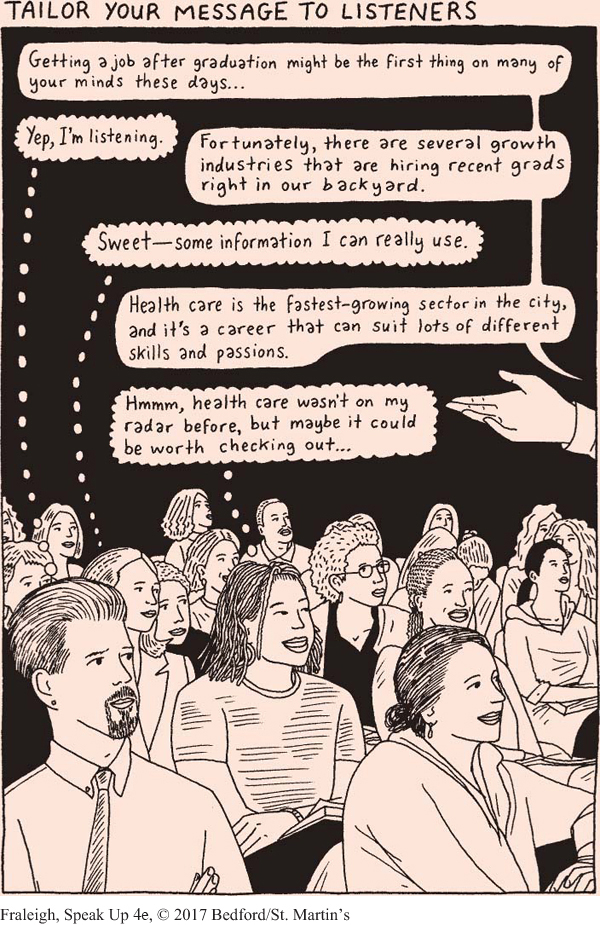

Representatives of the water district held a public meeting to discuss the new parking lot. Helena and Matt encouraged other farmers to attend the meeting, hoping to convince the representatives of the district that the plan should be halted or altered. At the meeting, Helena noticed that many local residents had come to sit in the audience. She also noted two reporters from the region’s two largest newspapers were present. After she and Matt consulted with each other, they each took to the podium to address the water district officials, but they used different messages intended for two separate audiences. Helena spoke at length about how important organic farming was to the local area—how local restaurants benefited and how low-income families (including many in the audience) received healthy and affordable vegetables and fruit be-cause of farms like hers. Matt then spoke about how senseless it was to destroy valuable and precious farmland (the soil at the ag park was unique and rich) and replace it with a parking lot—especially when other spaces for such a lot were available. When Matt spoke, he looked directly at the reporters—and then paraphrased the lyrics to an old Joni Mitchell song: “Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you got ’til it’s gone? You pave paradise, to put up a parking lot!”

When they finished, many local residents stood in line to speak—and all echoed or repeated what Helena and Matt had said. No one spoke to support the parking lot idea. The next day, news stories in both papers reported the meeting and the controversy. Both led with headlines about “Paving Paradise to Put Up a Parking Lot.” After local negative feedback and two stories that made the district plan appear foolish, the water district announced it would build a parking lot elsewhere.

As you can see by this (true-life) example, speakers who tailor their message to their listeners create enormous value for their audience and themselves, in some of the following ways:

Listeners become much more interested in and attentive to the speech.

They experience positive feelings toward the speaker when he or she has made an effort to understand listener concerns.

-

They open their minds to the speech message because it targets their specific needs, interests, and values.

They are also more open to being persuaded by a message that appears to be tailored for them and their specific interests.

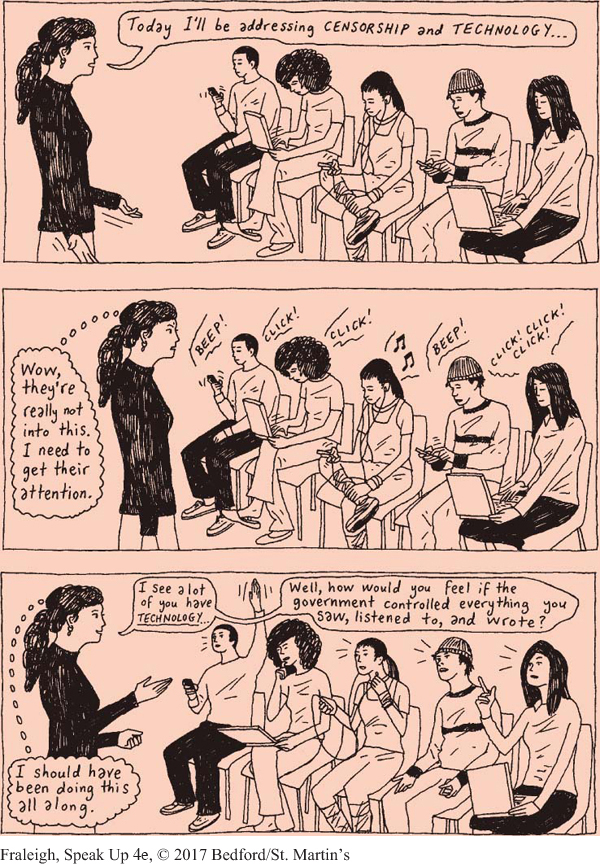

Of all the things Helena and Matt did right, the most important was to analyze their audience—recognizing that the residents and the reporters were their real audiences and that, by motivating and persuading them, they could increase the likelihood of persuading the water district to change its plans. Audience analysis is used in more than just public speaking. Even in everyday conversation, we continually shape our messages as we focus on the people we’re talking to. It’s not surprising that this skill is highly important in the context of public speaking. To learn about your audience before developing your speech, you will need to gather various kinds of information about your listeners.

In this chapter, we organize the types of information you will need to gather into the following categories—situational characteristics, demographics, common ground, prior exposure, and audience disposition. We also provide some tips for gathering these details, as well as suggestions for what to do if you discover halfway through a speech that you’ve misread your audience.

and

and  throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.

throughout the chapter for adaptive quizzing and online video activities.