Silver and Global Commerce

Comparison

Question

7N2l48gT0j0o/PLCQF8+owtdcPxPUoa32EDES0X+QFb8GzfYHGnxxxdmYMr4z47q0QpIeNC9+Z5UBxDZasHWMhUEQgRJHD0gj6TC5dGuiIE=[Answer Question]

Even more than the spice trade of Eurasia, it was the silver trade that gave birth to a genuinely global network of exchange (see Map 14.2). As one historian put it, silver “went round the world and made the world go round.”12 The mid-sixteenth-century discovery of enormously rich silver deposits in Bolivia, and simultaneously in Japan, suddenly provided a vastly increased supply of that precious metal. Spanish America alone produced perhaps 85 percent of the world’s silver during the early modern era. Spain’s sole Asian colony, the Philippines, provided a critical link in this emerging network of global commerce. Manila, the colonial capital of the Philippines, was the destination of annual Spanish shipments of silver, which were drawn from the rich mines of Bolivia, transported initially to Acapulco in Mexico, and from there shipped across the Pacific to the Philippines. This trade was the first direct and sustained link between the Americas and Asia, and it initiated a web of Pacific commerce that grew steadily over the centuries.

At the heart of that Pacific web, and of early modern global commerce generally, was China’s huge economy, and especially its growing demand for silver. In the 1570s, Chinese authorities consolidated a variety of tax levies into a single tax, which its huge population was now required to pay in silver. This sudden new demand for the white metal caused its value to skyrocket. It meant that foreigners with silver could now purchase far more of China’s silks and porcelains than before.

This demand set silver in motion around the world, with the bulk of the world’s silver supply winding up in China and much of the rest elsewhere in Asia. The routes by which this “silver drain” operated were numerous. Chinese, Portuguese, and Dutch traders flocked to Manila to sell Chinese goods in exchange for silver. European ships carried Japanese silver to China. Much of the silver shipped across the Atlantic to Spain was spent in Europe generally and then used to pay for the Asian goods that the French, British, and Dutch so greatly desired. Silver paid for some African slaves and for spices in Southeast Asia. The standard Spanish silver coin, known as a “piece of eight,” was used by merchants in North America, Europe, India, Russia, and West Africa as a medium of exchange. By 1600, it circulated widely in southern China. A Portuguese merchant in 1621 noted that silver “wanders throughout all the world . . . before flocking to China, where it remains as if at its natural center.”13

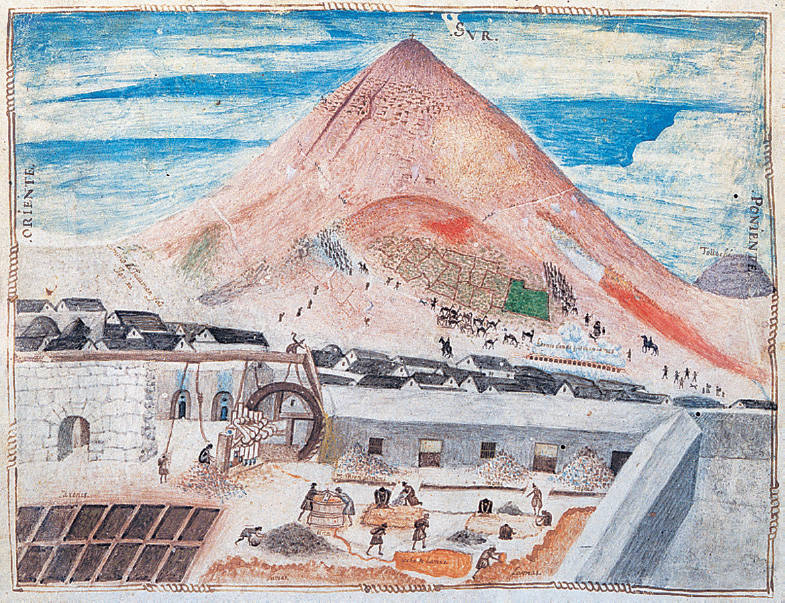

In its global journeys, silver transformed much that it touched. At the world’s largest silver mine in what is now Bolivia, the city of Potosí arose from a barren landscape high in the Andes, a ten-week mule trip away from Lima. “New people arrive by the hour, attracted by the smell of silver,” commented a Spanish observer in the 1570s. With 160,000 people, Potosí became the largest city in the Americas and equivalent in size to London, Amsterdam, or Seville. Its wealthy European elite lived in luxury, with all the goods of Europe and Asia at their disposal. Meanwhile, the city’s Native American miners worked in conditions so horrendous that some families held funeral services for men drafted to work the mines. One Spanish priest referred to Potosí as a “portrait of hell.”14 The environment too suffered, as highly intensive mining techniques caused severe deforestation, soil erosion, and flooding.

But the silver-fueled economy of Potosí also offered opportunity, not least to women. Spanish women might rent out buildings they owned for commercial purposes or send their slaves into the streets as small-scale traders, earning a few pesos for the household. Those less well-to-do often ran stores, pawnshops, bakeries, and taverns. Indian and mestiza women likewise opened businesses that provided the city with beverages, food, clothing, and credit.15

In Spain itself, which was the initial destination for much of Latin America’s silver, the precious metal vastly enriched the Crown, making Spain the envy of its European rivals during the sixteenth century. Spanish rulers could now pursue military and political ambitions in both Europe and the Americas far beyond the country’s own resource base. “New World mines,” concluded several prominent historians, “supported the Spanish empire.”16 Nonetheless, this vast infusion of wealth did not fundamentally transform the Spanish economy because it generated more inflation of prices than real economic growth. A rigid economy laced with monopolies and regulations, an aristocratic class that preferred leisure to enterprise, and a crusading insistence on religious uniformity all prevented the Spanish from using their silver windfall in a productive fashion. When the value of silver dropped in the early seventeenth century, Spain lost its earlier position as the dominant Western European power. More generally, the flood of American silver that circulated in Europe drove prices higher, further impoverished many, stimulated uprisings across the continent, and contributed to what historians sometimes call a “general crisis” of upheaval and instability in the seventeenth century.

Japan, another major source of silver production in the sixteenth century, did better. Its military rulers, the Tokugawa shoguns, used silver-generated profits to defeat hundreds of rival feudal lords and unify the country. Unlike their Spanish counterparts, the shoguns allied with the country’s vigorous merchant class to develop a market-based economy and to invest heavily in agricultural and industrial enterprises. Japanese state and local authorities alike acted vigorously to protect and renew Japan’s dwindling forests, while millions of families in the eighteenth century took steps to have fewer children by practicing late marriages, contraception, abortion, and infanticide. The outcome was the dramatic slowing of Japan’s population growth, the easing of an impending ecological crisis, and a flourishing, highly commercialized economy. These were the foundations for Japan’s remarkable nineteenth-century Industrial Revolution.

In China, silver deepened the already substantial commercialization of the country’s economy. To obtain the silver needed to pay their taxes, more and more people had to sell something—either their labor or their products. Communities that devoted themselves to growing mulberry trees, on which silkworms fed, had to buy their rice from other regions. Thus the Chinese economy became more regionally specialized. Particularly in southern China, this surging economic growth resulted in the loss of about half the area’s forest cover as more and more land was devoted to cash crops. No Japanese-style conservation program emerged to address this growing problem. An eighteenth-century Chinese poet, Wang Dayue, gave voice to the fears that this ecological transformation wrought:

Rarer, too, their timber grew, and rarer still and rarer

As the hills resembled heads now shaven clean of hair.

For the first time, too, moreover, they felt an anxious mood

That all their daily logging might not furnish them with fuel.17

China’s role in the silver trade is a useful reminder of Asian centrality in the world economy of the early modern era. Its large and prosperous population, increasingly operating within a silver-based economy, fueled global commerce, vastly increasing the quantity of goods exchanged and the geographic range of world trade. Despite their obvious physical presence in the Americas, Africa, and Asia, economically speaking Europeans were essentially middlemen, funneling American silver to Asia and competing with one another for a place in the rich markets of the East. The productivity of the Chinese economy was evident in Spanish America, where cheap and well-made Chinese goods easily outsold those of Spain. In 1594, the Spanish viceroy of Peru observed that “a man can clothe his wife in Chinese silks for [25 pesos], whereas he could not provide her with clothing of Spanish silks with 200 pesos.”18 Indian cotton textiles likewise outsold European woolen or linen textiles in the seventeenth century to such an extent that French laws in 1717 prohibited the wearing of Indian cotton or Chinese silk clothing as a means of protecting French industry.