|

|

Use one or more of the following suggestions to choose an experience to write about.

- Alone or with another student, list one or more broad topics — for example, Learn about Self, A Principle to Live By, Family Legend — and then brainstorm to come up with specific experiences in your life for each category. (Rational and pragmatic learners may prefer this kind of listing.)

- Flip through a family photo album, or page through a scrapbook, diary, or yearbook to remind you of events from the past. Other prewriting strategies, like freewriting or questioning, may also help trigger memories of experiences. (Spatial and emotional learners may prefer reviewing memorabilia.)

- Work backward: Think of a principle you live by, an object you value, or a family legend. How did it become so? (Abstract and independent learners may prefer working backward.)

After you have chosen your topic, make sure that it is memorable and vivid and that you can develop your main idea into a working thesis. |

Ask yourself these questions.

- Will my essay’s purpose be to express myself, inform, or persuade?

- Who is my audience? Will readers need any background information to understand my essay? Am I comfortable writing about my experience for this audience?

- What point of view best suits my purpose and audience? (In most cases, you will use first person to relate a personal experience.)

|

Use idea-generating strategies to recollect as many details about the experience or incident as possible.

- Replay the experience or incident in your mind’s eye. Jot down what you see, hear, smell, and feel — colors, dialogue, sounds, odors, and sensations — and how these details make you feel. (A broad range of learners — spatial, concrete, creative, and emotional — may prefer to generate ideas using mental imaging.)

- Write down the following headings: Scene, Key Actions, Key Participants, Key Lines of Dialogue, Feelings. Then brainstorm ideas for each and list them. (Pragmatic and rational learners may prefer to use brainstorming.)

- Describe the incident or experience to a friend. Have your friend ask you questions as you tell the story. Jot down the details that the telling and questioning helped you recall. (Social and verbal learners may prefer to use storytelling.)

As you gather details for your narrative, be sure to include those that are essential to an effective narrative.

- Describe the scene: Include relevant sensory details to allow your readers to feel as if they are there. Choose details that point to or hint at the narrative’s main point, and avoid those that distract readers from the main point.

- Include key actions: Choose actions that create tension, build it to a climax, and resolve it. Answer questions like these:

Why did the experience or incident occur? What events led up to it, what was the turning point, and how was it resolved? What were its short- and long-term outcomes? What is its significance?

- Describe key participants: Concentrate on the appearance and actions of only those people who were directly involved, and include details that help highlight relevant character traits.

- Quote key lines of dialogue: Include dialogue that is interesting, revealing, and related to the main point of the narrative. To make sure the dialogue sounds natural, read the lines aloud or ask a friend to do so.

- Capture feelings: How did you feel during the incident, how did you reveal your feelings, and how did others react to you? How do you feel about the incident now? What have you learned from it?

Use at least two idea-generating strategies, and then work with a classmate to evaluate your ideas. |

Try these suggestions to help you evaluate your ideas.

- Reread everything you have written. (Sometimes reading your notes aloud is helpful.)

- Highlight the most relevant material, and cross out any material that does not directly support your main point. Then copy and paste the usable ideas to a new document to consult while drafting.

- Collaborate in small groups, take turns narrating your experience and stating its main point and having classmates tell you . . .

- how they react to the story.

- what more they need to know about it.

- how effectively the events and details support your main point.

|

|

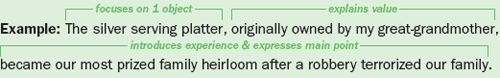

Make the main point of your narrative clear and effective by focusing your thesis. For example, a student who decided to write about a robbery at her family’s home devised the following focused thesis statement for her narrative. Team up with classmates to test your thesis. Is it clear? Is it interesting? Provide feedback to help your partner focus the thesis more effectively. Consider the best placement for your thesis. A thesis statement may be placed at the beginning (as in “Right Place, Wrong Face”) or at the end of a narrative, or it may be implied. (Even if you don’t state your thesis explicitly in your essay, having a focused thesis written down can help you craft your narrative.) (Note: Once you have a focused thesis, you may need to do some additional prewriting, or you may need to revise your thesis as you draft. Return to the steps above as needed.) |

Organize your narrative. You may use chronological order from beginning to end or present some events using flashbacks or foreshadowing for dramatic effect. To help you determine the best sequence for your narrative, try the following.

- Write a brief description of each event on an index card. Highlight the card that contains the climax. Experiment with various ways of arranging your details by rearranging the cards. (Pragmatic learners may benefit from using index cards this way.)

- Draw a graphic organizer of the experience or incident using Figure 12.1 as a model. (Spatial learners may benefit from drawing a graphic organizer.)

- Create a list of the events, and then cut and paste them to experiment with different sequences. (Verbal learners may benefit from creating a list.)

|

Use the following guidelines to keep your narrative on track.

- The introduction should set up the sequence of events. It may also contain your thesis.

- The body paragraphs should build tension and follow a clear order of progression. Use transitional words and phrases, such as during, after, and finally, to guide readers. Most narratives use the past tense (“Yolanda discovered the platter . . .”), but fast-paced, short narratives may use the present (“Yolanda discovers the platter . . .”). Avoid switching between the two unless the context clearly requires it.

- The conclusion is unlikely to require a summary. Instead, try . . .

- making a final observation about the experience or incident, (Example: “Overall, I learned a lot more about getting along with people than I did about how to prepare fast food.”)

- asking a probing question, (Example: “Although the visit to Nepal was enlightening for me, do the native people really want or need us there?”)

- suggesting a new but related direction of thought, (Example: An essay on racial profiling might conclude by suggesting that police sensitivity training might have changed the outcome of the situation.)

- referring to the beginning of the essay, (Example: “Right Place, Wrong Face”) or restating the thesis in different words (Example: “Being Double”).

|

|

Use “Figure 12.3, Flowchart for Revising a Narrative Essay,” to evaluate and revise your draft. |

|

Refer to Chapter 10 for help with . . .

- editing sentences to avoid wordiness, make your verb choices strong and active, and make your sentences clear, varied, and parallel, and

- editing words for tone and diction, connotation, and concrete and specific language.

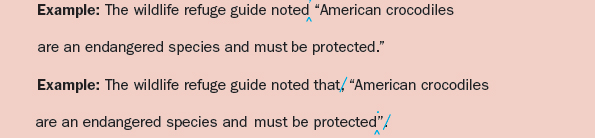

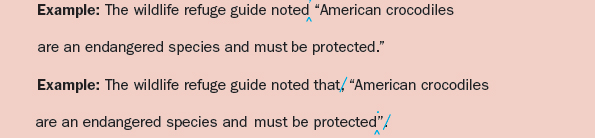

Pay particular attention to dialogue:

- Each quotation by a new speaker should start a new paragraph.

- Use commas to separate each quotation from the phrase that introduces it unless the quotation is integrated into your sentence. If your sentence ends with a quotation, the period should be inside the quotation marks.

|