“The Language of Junk Food Addiction: How to “Read” a Potato Chip,” Michael Moss

READING: DIVISION

The Language of Junk Food Addiction: How to “Read” a Potato Chip

MICHAEL MOSS

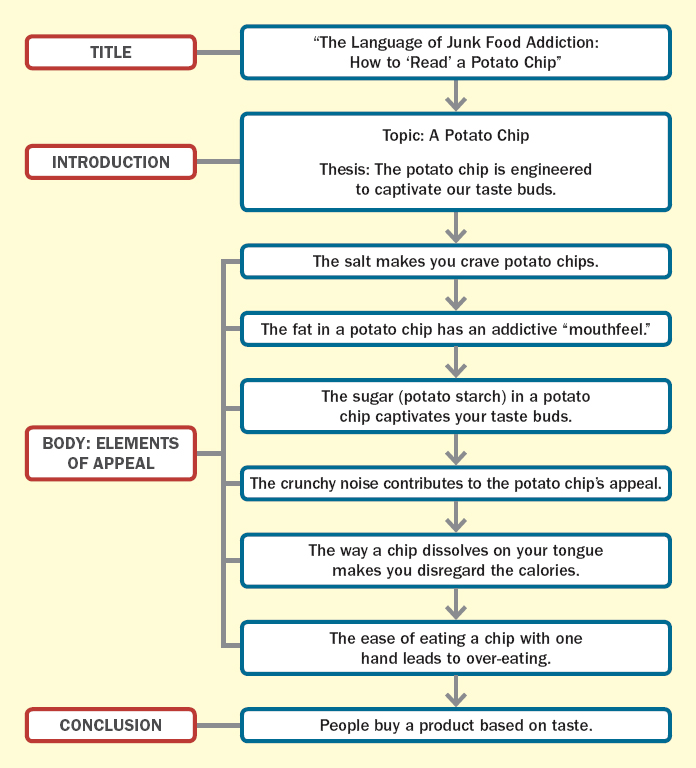

Michael Moss is a Pulitzer Prize–winning investigative reporter for The New York Times, where he has worked since 2000. Before coming to The Times, he reported for publications including The Daily Sentinel (in Grand Junction, Colorado), The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, New York Newsday, and The Wall Street Journal. He has also published two books, Palace Coup: The Inside Story of Harry and Leona Helmsley (1989) and Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (2013). The interview from which this selection was taken was based on Moss’s work for Salt Sugar Fat. Figure 17.2 provides a graphic organizer for "The Language of Junk Food Addiction." Before studying that graphic organizer, read this division essay and try to determine what parts the author divides the topic into and what his principle of division is.

Betcha can’t eat just one.

1

These five words captured the essence of the potato chip far better than anyone at Frito-Lay could have imagined. In the ‘60s, the sentiment might have seemed cute and innocent — it’s hard not to pig out on potato chips, they’re tasty, they’re fun. But today the familiar phrase has a sinister connotation because of our growing vulnerability to convenience foods, and our growing dependence on them.

2

As I researched Salt, Sugar, Fat, I was surprised to learn about the meticulously crafted allure of potato chips (which I happen to love). When you start to deconstruct the layers of the chip’s appeal, you start to see why this simple little snack has the power to make a profound claim on our attention and appetite. “Betcha can’t eat just one” starts sounding less like a lighthearted dare — and more like a kind of promise. The food industry really is betting on its ability to override the natural checks that keep us from overeating.

3

Here’s how it works.

4

It starts with salt, which sits right on the outside of the chip. Salt is the first thing that hits your saliva, and it’s the first factor that drives you to eat and perhaps overeat. Your saliva carries the salty taste through the neurological channel to the pleasure center of the brain, where it sends signals back: “Hey, this is really great stuff. Keep eating.”

5

The industry calls this salty allure a food’s “flavor burst,” and I was surprised to learn just how many variations on this effect there are. The industry creates different varieties of salt for different kinds of processed foods: everything from fine powders that blend easily into canned soups, to big chunky pyramid-shaped granules with flat sides that stick better to food (hollowed out on the inside for maximum contact with the saliva).

6

Then, of course, there’s fat. Potato chips are soaked in fat. And fat is fascinating because it’s not one of the five basic tastes that Aristotle identified way back when — it’s a feeling. Fat is the warm, gooey sensation you get when you bite into a toasty cheese sandwich — or you get just thinking about such a sandwich (if you love cheese as much as I do). There’s a nerve ending that comes down from the brain almost to the roof of the mouth that picks up the feel of fat, and the industry thus calls the allure of fat “mouthfeel.”

7

The presence of fat, too, gets picked up by nerve endings and races along the neurological channel to the pleasure center of the brain. Which lights up, as strongly as it lights up for sugar. There are different kinds of fats — some good — but it’s the saturated fats, which are common in processed foods, that are of most concern to doctors. They’re linked to heart disease if over-consumed. And since fats have twice as many calories as sugar, they can be problematic from an obesity standpoint.

8

But potato chips actually have the entire holy trinity: They’re also loaded with sugar. Not added sugar — although some varieties do — but the sugar in most chips is in the potato starch itself, which gets converted to sugar in the moment the chip hits the tongue. Unlike fat, which studies show can exist in unlimited quantities in food without repulsing us, we do back off when a food is too sweet. The challenge is to achieve just the right depth of sweetness without crossing over into the extreme. The industry term for this optimal amount of sugar is called the “bliss point.”

9

So you’ve got all three of the big elements in this one product. But salt, sugar, and fat are just the beginning of the potato chip’s allure. British researchers, for instance, have found that the more noise a chip makes when you eat it, the better you’ll like it and the more apt you are to eat more. So chip companies spend a lot of effort creating a perfectly noisy, crunchy chip.

10

The chip has an amazing textural allure, too, a kind of meltiness on the tongue. The ultraprocessed food product most admired by food company scientists in this regard is the Cheeto, which rapidly dissolves in your mouth. When that happens, it creates a phenomenon that food scientists call “vanishing caloric density.” Which refers to the phenomenon that as the Cheeto melts, your brain interprets that melting to mean that the calories in the Cheeto have disappeared as well. So they tend to uncouple your brain from the breaks that keep your body from overeating. And the message coming back from the brain is: “Hey, you might as well be eating celery for all I care about all the calories in those disappearing Cheetos. Go for it.”

11

Then there’s the whole act of handling the chip — the fact that we move it with our hand directly to the mouth. When you move a food directly to your mouth with your hand there are fewer barriers to overeating. You don’t need to wait until you have a fork, or a spoon, or a plate to eat. You can eat with one hand while doing something else. These handheld products lead to what nutrition scientists call “mindless eating” — where we’re not really paying attention to what we’re putting in our mouths. This has been shown to be hugely conducive to over-eating. One recent example is the Go-Gurt yogurt that comes in a collapsible tube. Once you open it, you can just squeeze out the yogurt with one hand while you’re playing a computer game with the other.

12

The bottom line, which everyone in the food industry will tell you, is taste. They’re convinced that a good number of us will talk a good game on nutrition and health, but when we walk through the grocery store, we’ll look for and buy the products that taste the best. And that’s the cynical view: They will do nothing to improve the health profile of their products that will jeopardize taste. They’re as hooked on profits as they are on salt, sugar, fat.

13