5.4 Properties of the Definite Integral

369

OBJECTIVES

When you finish this section, you should be able to:

- Use properties of the definite integral (p. 369)

- Work with the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals (p. 372)

- Find the average value of a function (p. 373)

We have seen that there are properties of limits that make it easier to find limits, properties of continuity that make it easier to determine continuity, and properties of derivatives that make it easier to find derivatives. Here, we investigate several properties of the definite integral that will make it easier to find integrals.

1 Use Properties of the Definite Integral

NOTE

From now on, we will refer to Parts 1 and 2 of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus simply as the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus.

Proofs of most of the properties in this section require the use of the definition of the definite integral. However, if the condition is added that the integrand is continuous, then the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus can be used to establish the properties. We will use this added condition in the proofs included here.

IN WORDS

The integral of a sum equals the sum of the integrals.

THEOREM The Integral of the Sum of Two Functions

If two functions \(f\) and \(g\) are continuous on the closed interval \([a,b]\), then \[ \begin{equation*} \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{\bbox[5pt]{ \int_{a}^{b}[ f(x)+g(x)] \,dx=\int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx+\int_{a}^{b}g(x)\,dx }}\tag{1} \end{equation*} \]

Proof

Since \(f\) and \(g\) are continuous on \([a,b],\) then the definite integral of each function exists. Let \(F\) and \(G\) be an antiderivative of \(f\) and \(g,\) respectively, on \((a,b) \). Then \(F' =f\) and \(G^{\prime} =g\) on \((a,b) \).

Also, since \((F + G)' = F^\prime + G' = f + g,\) then \(F+G\) is an antiderivative of \(f+g\) on \((a,b) .\) Now \[ \begin{eqnarray*} \int_{a}^{b}[f(x)+g(x)]\,dx=\bigg[F(x)+G(x)\bigg] _{a}^{b} &=&[F(b)+G(b)]-[F(a)+G(a)] \\ &=&[F(b)-F(a)]+[G(b)-G(a)] \\ &=&{\int_{a}^{b}{f(x)\,dx+{\int_{a}^{b}{g(x)\,dx}}}} \end{eqnarray*} \]

Using Property (1) of the Definite Integral

\[ \begin{eqnarray*} \int_{0}^{1}(x^{2}+e^{x})\,dx &=& \int_{0}^{1}x^{2}dx+\int_{0}^{1}e^{x}\,dx= \left[ \dfrac{x^{3}}{3}\right] _{0}^{1}+ \Big[ e^{x}\Big] _{0}^{1} \\[4pt] &=&\left[ \dfrac{1^{3}}{3}-0\right] +\Big[ e^{1}-e^{0}\Big] =\dfrac{1}{3}+e-1=e-\dfrac{2}{3} \end{eqnarray*} \]

NOW WORK

Problem 13.

IN WORDS

A constant factor can be factored out of an integral.

THEOREM The Integral of a Constant Times a Function

Suppose a function \(f\) is continuous on the closed interval \([a,b]\). If \(k\) is a constant, then \[\begin{equation*} \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{\bbox[5pt]{ \int_{a}^{b}kf(x)\,dx=k\int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx } }\tag{2} \end{equation*}\]

You are asked to prove this theorem in Problem 93.

370

Using Property (2) of the Definite Integral

\[ \begin{eqnarray*} {\int_{1}^{e}}\dfrac{{3}}{x}{\,dx=3} {{\,{\int_{1}^{e}}}}\dfrac{1}{x}{dx=3} \Big[ \ln \vert x\vert \Big] _{1}^{e}={3}\left( {\ln \,}e-\ln 1\right) =3(1-0) =3 \end{eqnarray*} \]

NOW WORK

Problem 15.

The two properties above can be extended as follows:

THEOREM

Suppose each of the functions \(f_{{1}}\), \(f_{{2}}, \ldots , f_{n}\) is continuous on the closed interval \([a,b]\). If \(k_{{1}}\), \(k_{{2}}, \ldots\), \(k_{n}\) are constants, then \[\begin{equation*} \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{\bbox[5pt]{ \begin{array}{@{\hspace*{-6pt}}lll@{}} &&\int_{a}^{b}\left[ k_{{1}}f_{{1}}(x)+k_{{2}}f_{{2}}(x)+\cdots +\,k_{n} f_{n}(x)\right]\,dx \\[9pt] && = k_{{1}}\int_{a}^{b}f_{{1}}(x)\,dx + k_{{2}} \int_{a}^{b}f_{{2}}(x)\,dx+\cdots + k_{n}\int_{a}^{b}f_{n}(x)\,dx \end{array}} }\tag{3} \end{equation*}\]

You are asked to prove this theorem in Problem 94.

Using Property (3) of the Definite Integral

Find \(\int_{1}^{2}\dfrac{3x^{3}-6x^{2}-5x+4}{2x}dx\).

Solution The function \(f(x) =\dfrac{3x^{3}-6x^{2}-5x+4}{2x}\) is continuous on the closed interval \([1,2] \). Using algebra and the properties of the definite integral, we get \[ \begin{eqnarray*} \int_{1}^{2}\dfrac{3x^{3}-6x^{2}-5x+4}{2x}dx &=&\int_{1}^{2}\left[\dfrac{3}{2} x^{2}- 3x- \dfrac{5}{2}+\dfrac{2}{x}\right] dx\\ &=& \int_{1}^{2} \dfrac{3}{2} x^{2}dx-\int_{1}^{2} 3x\, dx- \int_{1}^{2} \dfrac{5}{2} \, dx+\int_{1}^{2}\dfrac{2}{x}~dx \\[4pt] &=& \dfrac{3}{2}\int_{1}^{2}x^{2}~dx-3\int_{1}^{2}x\, dx-\dfrac{5}{2}\int_{1}^{2}~dx+2\int_{1}^{2}\dfrac{1}{x}~dx \\ &=& \dfrac{3}{2} \left[ \dfrac{x^{3}}{3}\right] _{1}^{2} -3 \left[ \dfrac{x^{2}}{2}\right] _{1}^{2} -\dfrac{5}{2} \Big[x\Big]_{1}^{2} +2 \Big[\ln \vert x\vert \Big]_{1}^{2} \\ &=&\dfrac{1}{2} ( 8-1) - 3\left( 2-\dfrac{1}{2}\right) -\dfrac{5}{2}(2-1) + 2( \ln 2- \ln 1 ) \\ &=&-\dfrac{7}{2}+2\ln 2\approx -2.114 \end{eqnarray*} \]

NOW WORK

Problem 27.

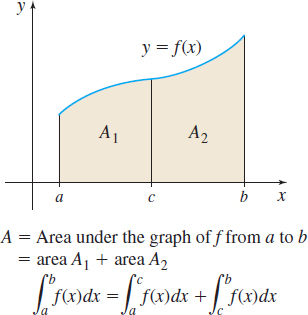

The next property states that a definite integral of a function \(f\) from \(a \) to \(b\) can be evaluated in pieces.

THEOREM

If a function \(f\) is continuous on an interval containing the numbers \(a\), \(b\), and \(c\), then \[\begin{equation*} \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{\bbox[5pt]{ \int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx=\int_{a}^{c}f(x)\,dx+\int_{c}^{b}f(x)\,dx } }\tag{4} \end{equation*}\]

A proof of this theorem is given in Appendix B.

371

In particular, if \(f\) is continuous and nonnegative on a closed interval \([a,b]\) and if \(c\) is a number between \(a\) and \(b\), then this property has a simple geometric interpretation, as seen in Figure 24.

Using Property (4) of the Definite Integral

- If \(f\) is continuous on the closed interval \([2,7]\), then \[ \int_{2}^{7}f(x)\,dx=\int_{2}^{4}f(x)\,dx+\int_{4}^{7}f(x)\,dx \]

- If \(g\) is continuous on the closed interval \([3,25]\), then \[ \int_{3}^{10}g(x)\,dx=\int_{3}^{25}g (x)\,dx+ \int_{25}^{10}g(x) dx \]

Example 4(b) illustrates that the number \(c\) need not lie between \(a\) and \(b\).

NOW WORK

Problem 43.

Property (4) is useful when integrating piecewise-defined functions.

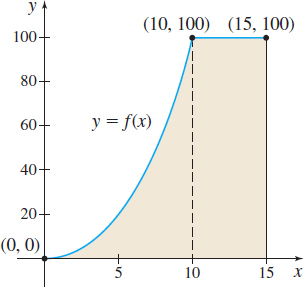

Using Property (4) of the Definite Integral

Find the area \(A\) under the graph of

\[ f(x) =\left\{ \begin{array}{c@{ }c@{ }ccc} x^{2} & \hbox{if} & 0 & \leq x &\lt10 \\ 100 & \hbox{if} & 10 &\leq x & \leq 15 \end{array} \right. \]

from \(0\) to \(15.\)

Solution See Figure 25. Since \(f\) is nonnegative on the closed interval \([0,15] ,\) then \(\int_{0}^{15}f(x)\, dx\) equals the area \(A\) under the graph of \(f\) from \(0\) to \(15.\) Since \(f\) is continuous on \([0,15],\) \[ \begin{eqnarray*} \int_{0}^{15}f(x)\, dx &=& \int_{0}^{10}f(x)\, dx+\int_{10}^{15}f(x)\, dx=\int_{0}^{10}x^{2}dx+\int_{10}^{15}100\,dx \\[4.5pt] &=& \left[\dfrac{x^{3}}{3}\right] _{0}^{10}+ \Big[100x\Big] _{10}^{15}=\dfrac{1000}{3}+500=\dfrac{2500}{3} \end{eqnarray*} \]

The area under the graph of \(f\) is approximately 833.33 square units.

NOW WORK

Problem 35.

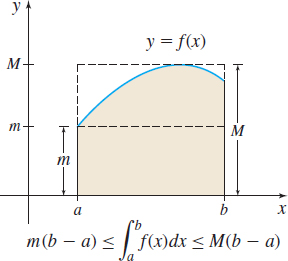

The next property establishes bounds on a definite integral.

THEOREM Bounds on an Integral

If a function \(f\) is continuous on a closed interval \([a,b]\) and if \(m\) and \(M\) denote the absolute minimum value and the absolute maximum value, respectively, of \(f\) on \([a,b]\), then \[\begin{equation*} \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{\bbox[5pt]{ m(b-a)\leq \int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\leq M\,(b-a) }}\tag{5} \end{equation*}\]

A proof of this theorem is given in Appendix B.

If \(f\) is nonnegative on \([a,b]\), then the inequalities in (5) have a geometric interpretation. In Figure 26, the area of the shaded region is \({\int_{a}^{b}{f(x)\,dx}}\). The smaller rectangle has width \(b-a,\) height\(\, m\), and area equal \(m(b-a).\) The larger rectangle has width \(b-a,\) height \(M\), and area \(M(b-a)\). These three areas are numerically related by the inequalities in the theorem.

372

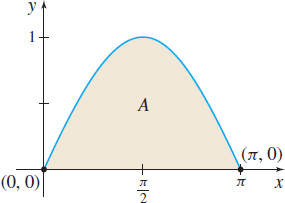

Using Property (5) of Definite Integrals

- Find an upper estimate and a lower estimate for the area \(A\) under the graph of \(f(x) =\sin x\) from \(0\) to \(\pi \).

- Find the actual area under the graph.

Solution The graph of \(f\) is shown in Figure 27. Since \(f(x) \geq 0\) for all \(x\) in the closed interval \([ 0,\pi ] \), the area \(A\) under its graph is given by the definite integral, \(\int_{0}^{\pi }\sin x~dx\).

(a) From the Extreme Value Theorem, \(f\) has an absolute minimum value and an absolute maximum value on the interval \([0,\pi] .\) The absolute maximum of \(f\) occurs at \(x=\dfrac{\pi}{2},\) and its value is \(f \left( \dfrac{\pi }{2}\right) =\sin \dfrac{\pi }{2}=1.\) The absolute minimum occurs at \(x=0\) and at \(x=\pi \); the absolute minimum value is \(f (0) =\sin 0=0=f (\pi)\). Using the inequalities in (5), the area under the graph of \(f\) is bounded as follows:

NEED TO REVIEW?

The Extreme Value Theorem is discussed in Section 4.2, p 265.

\[ 0\leq \int_{0}^{\pi }\sin x~dx\leq \pi \]

(b) The actual area under the graph is \[ A= \int_{0}^{\pi}\sin x\,dx= \bigg[-\cos x\bigg] _{0}^{\pi }=-\cos \pi +\cos 0=1+1=2\hbox{ square units} \]

NOW WORK

Problem 53.

2 Work with the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals

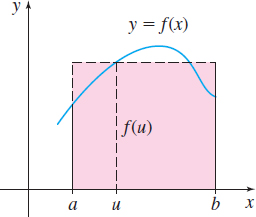

Suppose \(f\) is a function that is continuous and nonnegative on a closed interval \([a,b] .\) Figure 28 suggests that the area under the graph of \(f\) from \(a\) to \(b\), \(\int_{a}^{b} f(x)\,dx\), is equal to the area of some rectangle of width \(b-a\) and height \(f(u)\) for a some choice (or choices) of \(u\) in the interval \([a,b].\)

In more general terms, for every function \(f\) that is continuous on a closed interval \([a,b] ,\) there is some number \(u\) (not necessarily unique) in the interval \([a,b] \) for which \[ \int_{a}^{b}f(x)\, dx=f(u) (b-a) \]

This result is known as the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals.

THEOREM Mean Value Theorem for Integrals

If a function \(f\) is continuous on a closed interval \([a,b]\), there is a real number \(u\), \(a\,\leq \,u\,\leq \,b\), for which \[\bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{\bbox[5pt]{ \int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx=f(u)(b-a) }}\tag{6} \]

Proof

Let \(f\) be a function that is continuous on a closed interval \([a,b] \).

If \(f\) is a constant function, say, \(f(x) =k,\) on \([a,b]\), then \[ \int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx= \int_{a}^{b}k\,dx =k(b-a) =f(u)(b-a) \]

for any choice of \(u\) in \([a,b]\).

If \(f\) is not a constant function on \([a,b]\), then by the Extreme Value Theorem, \(f\) has an absolute maximum and an absolute minimum on \([a,b]\). Suppose \(f\) assumes its absolute minimum at the number \(c\) so that \(f(c)=m\); and suppose \(f\) assumes its absolute maximum at the number \(C\) so that \(f (C)\,=M\). Then by the Bounds on an Integral Theorem (5), we have \[ m(b-a)\leq {\int_{a}^{b}{f(x)\,dx\leq M(b-a)}}\qquad \hbox{for all } x\hbox{ in }[a,b] \]

373

We divide each part by \((b-a) \) and replace \(m\) by \(f(c)\) and \(M\) by \(f (C)\). Then \[ f(c)\leq \dfrac{{1}}{{b-a}}\int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\leq f(C) \]

NEED TO REVIEW?

The Intermediate Value Theorem is discussed in Section 1.3, pp. 100-102.

Since \(\dfrac{1}{b-a}\int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx\) is a real number between \(f(c)\) and \(f (C)\), it follows from the Intermediate Value Theorem that there is a real number \(u\) between \(c\) and \(C\), for which \[ f(u)\,={\dfrac{{1}}{{b-a}}}{\int_{a}^{b}{f(x)\,dx}} \]

That is, there is a real number \(u\), \(a\leq u\leq b\), for which \[ {\int_{a}^{b}{f(x)\,dx}}=f(u)\,(b-a) \]

Using the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals

Find the number(s) \(u\) guaranteed by the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals for \(\int_{2}^{6}x^{2}dx.\)

Solution The Mean Value Theorem for Integrals states there is a number \(u,\) \(2\leq u\leq 6,\) for which \[ \int_{2}^{6}x^{2}dx=f(u) (6-2) =4u^{2}\qquad\qquad {\color{#0066A7}{\hbox{\(f(u)=u^2\)}}} \]

We integrate to obtain \[ \int_{2}^{6}x^{2}dx=\left[\dfrac{x^{3}}{3}\right] _{2}^{6}=\dfrac{1}{3}(216-8) =\dfrac{208}{3} \]

Then \[ \begin{eqnarray*} \begin{array}{rl@{\qquad}l@{\hskip-2pc}} \dfrac{208}{3} &= 4u^{2} \\ u^{2} &= \dfrac{52}{3} & {\color{#0066A7}{2\leq u\leq 6}} \\ u &= \sqrt{\dfrac{52}{3}}\approx 4.163 & {\color{#0066A7}{\hbox{Disregard the negative solution since \(u>0\).}}} \end{array} \end{eqnarray*} \]

NOW WORK

Problem 55.

3 Find the Average Value of a Function

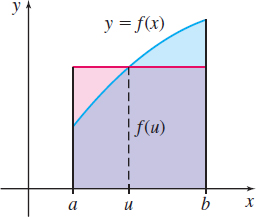

We know from the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals that if a function \(f\) is continuous on a closed interval \([a,b]\), there is a real number \(u\), \(a\,\leq \,u\,\leq \,b\), for which \[ \int_{a}^{b}f(x) \,dx = f(u) (b-a) \]

This means that if the function \(f\) is also nonnegative on the closed interval \([a,b] ,\) the area enclosed by a rectangle of height \(f(u) \) and width \(b-a\) equals the area under the graph of \(f\) from \(a\) to \(b.\) See Figure 29.

So if we replace \(f(x) \) on \([a,b] \) by \(f(u) ,\) we get a region with the same area. Consequently, \(f(u) \) can be thought of as an average value, or mean value, of \(f\) over \([a,b]\).

We can obtain the average value of \(f\) over \([a,b]\) for any function \(f\) that is continuous on the closed interval \([a,b]\) by partitioning \([a,b]\) into \(n\) subintervals \[ \lbrack a,x_{1}], \lbrack x_{1},x_{2}], \ldots , \lbrack x_{i-1},x_{i}], \ldots , \lbrack x_{n-1},b] \]

374

each of length \(\Delta x=\dfrac{b-a}{n}\), and choosing a number \(u_{i}\) in each of the \(n\) subintervals. Then an approximation of the average value of \(f\) over the interval \([a,b]\) is \[ \begin{equation*} \dfrac{{f(u_{1})+f(u_{2})+\cdots +f(u}_{n}{)}}{{n}}\tag{7} \end{equation*} \]

Now we multiply (7) by \(\dfrac{b-a}{b-a}\) to obtain \[ \begin{array}{@{\hspace*{-2pc}}lcc} \dfrac{{f(u_{1})+f(u_{2})+\cdots +f(u_{n})}}{{n}} &=&{\dfrac{{1}}{{b-a}}} \left[ f(u_{1}){\dfrac{{b-a}}{{n}}}+f(u_{2}){\dfrac{{b-a}}{{n}}} \right. + \left. \cdots +f(u_{n}){\dfrac{{b-a}}{{n}}}\right] \\ &=&{\dfrac{{1}}{{b-a}}}[ f(u_{1})\,\Delta x+f(u_{2})\,\Delta x+\cdots +f(u_{n})\,\Delta x]\\ & =& {\dfrac{{1}}{{b-a}}}{\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}{f(u_{i})\,\Delta x}} \end{array} \]

This sum approximates the average value of \(f\). As the length of each subinterval gets smaller, the sums become better approximations to the average value of \(f\) on \([a,b] \). Furthermore, \({\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}\,{f(u_{i})\,\Delta x}}\) are Riemann sums, so \(\lim\limits_{n\rightarrow \infty}\,{\sum\limits_{i=1}^{n}\,{f(u_{i})\,\Delta x}}\) is a definite integral. This suggests the following definition:

IN WORDS

The average value \(\bar{y} =\dfrac{1}{b-a}\int_{a}^{b}{f(x)\,dx}\) of a function \(f\) equals the value \({f(u)}\) in the Mean Value Theorem for Integrals.

spanDEFINITIONspan Average Value of a Function over an Interval

Let \(f\) be a function that is continuous on the closed interval \([a,b] .\) The average value \({\boldsymbol {\bar{y}}}\) of \({\boldsymbol f}\) over \(\boldsymbol{[a,b]}\) is \[\bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{\bbox[5pt]{ \bar{y}=\dfrac{1}{b-a} \int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx }}\tag{8} \]

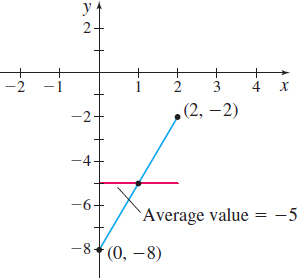

Finding the Average Value of a Function

Find the average value of \(f(x)=3x-8\) on the closed interval \([0,2] .\)

Solution The average value of \(f(x)=3x-8\) on the closed interval \([0,2]\) is given by \[ \begin{eqnarray*} \bar{y} &=&\dfrac{1}{b-a}\int_{a}^{b}f(x)\,dx=\dfrac{1}{2-0}{\int_{0}^{2}}(3x-8) dx\\ &=& \dfrac{1}{2}\left[\dfrac{3x^{2}}{2}-8x \right] _{0}^{2} =\dfrac{1}{2}(6-16) =-5 \end{eqnarray*} \]

The average value of \(f\) on \([0,2] \) is \(\bar{y}=-5.\)

The function \(f\) and its average value are graphed in Figure 30.

NOW WORK

Problem 61.