From Property to Democracy

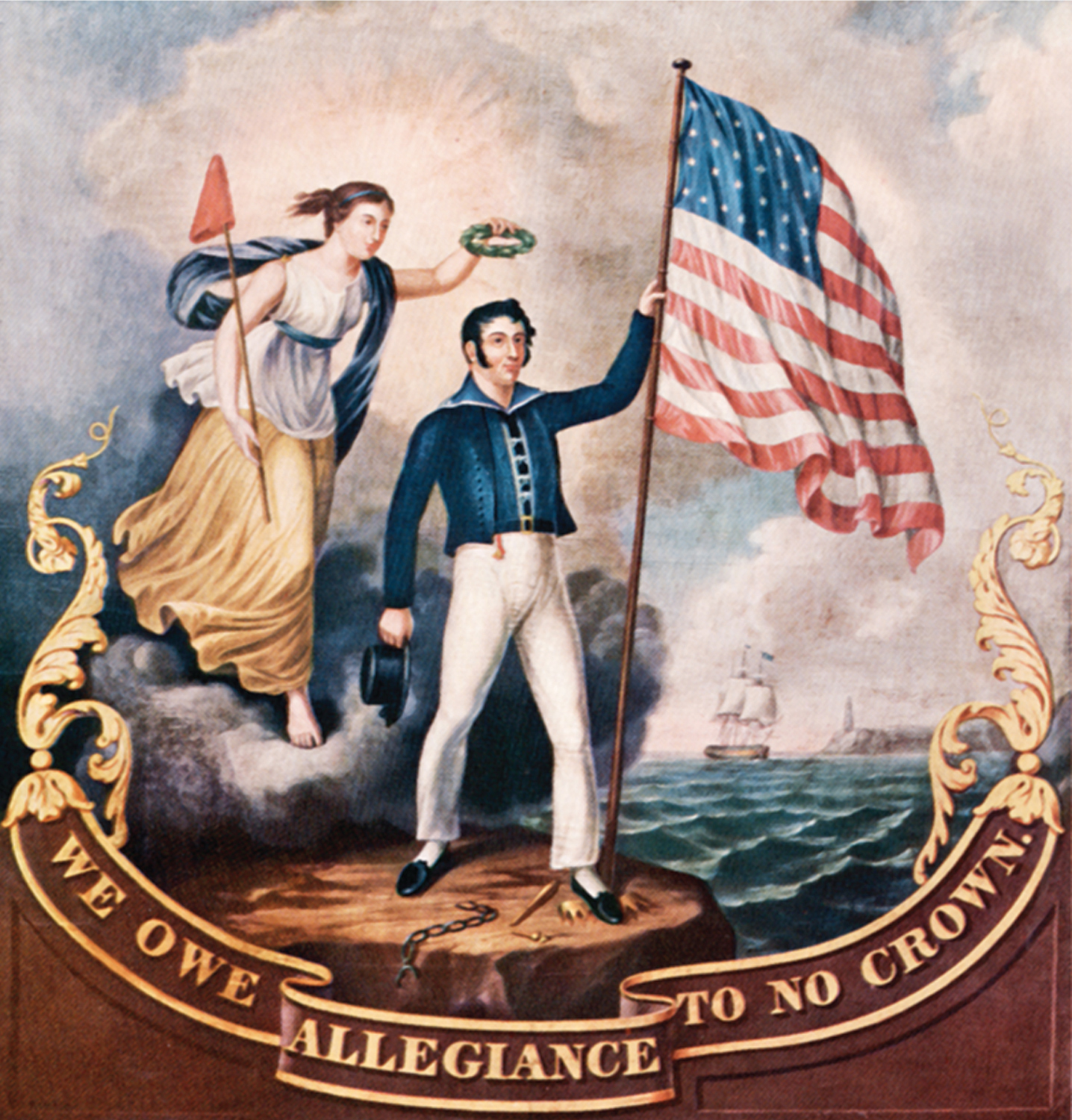

Up to 1820, presidential elections occurred in the electoral college, at a remove from ordinary voters. The excitement generated by state elections, however, created an insistent pressure for greater democratization of presidential elections.

In the 1780s, twelve of the original thirteen states enacted property qualifications based on the time-

Not everyone favored expanded suffrage; propertied elites tended to defend the status quo. But others managed to get legislatures to call new constitutional conventions in which questions of suffrage, balloting procedures, apportionment, and representation were debated. By 1820, half a dozen states passed suffrage reform, some choosing universal manhood suffrage while others tied the vote to tax status or militia service. In the remainder of the states, the defenders of landed property qualifications managed to delay expanded suffrage for two more decades. But it was increasingly hard to persuade the disfranchised that landowners alone had a stake in government. Proponents of the status quo began to argue instead that the “industry and good habits” necessary to achieve a propertied status in life were what gave landowners the right character to vote. Opponents fired back blistering attacks. One delegate to New York’s constitutional convention said, “More integrity and more patriotism are generally found in the labouring class of the community than in the higher orders.” Owning land was no more predictive of wisdom and good character than it was of a person’s height or strength, said another observer.

Both sides of the debate generally agreed that character mattered, and many ideas for ensuring an electorate of proper wisdom came up for discussion. The exclusion of paupers and felons convicted of “infamous crimes” found favor in legislation in many states. Requiring literacy tests and raising the voting age to a figure in the thirties were debated but ultimately discarded. The exclusion of women required no discussion in the constitutional conventions, so firm was the legal power of feme covert mandating the subjugation of married women to their husbands. But in one exceptional moment, at the Virginia constitutional convention in 1829, a delegate wondered aloud why unmarried women older than twenty-

Free black men’s enfranchisement was another story, generating much discussion at all the conventions. Under existing freehold qualifications, a small number of propertied black men could vote; universal or taxpayer suffrage would inevitably enfranchise many more. Many delegates at the various state conventions spoke against that extension, claiming that blacks as a race lacked prudence, independence, and knowledge. With the exception of New York, which retained the existing property qualification for black voters as it removed it for whites, the general pattern was one of expanded suffrage for whites and a total eclipse of suffrage for blacks.