Dangers Overseas: The Barbary Wars

Jefferson’s desire to keep government and the military small met a severe test in the western Mediterranean Sea, where U.S. trading interests ran afoul of several states on the northern coast of Africa. For well over a century, Morocco, Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli, called the Barbary States by Americans, controlled all Mediterranean shipping traffic by demanding large annual payments (called “tribute”) for safe passage. Countries electing not to pay found their ships and crews at risk for seizure. After several years in the 1790s when some hundred American crew members were taken captive and held in slavery, the United States agreed to pay $50,000 a year in tribute.

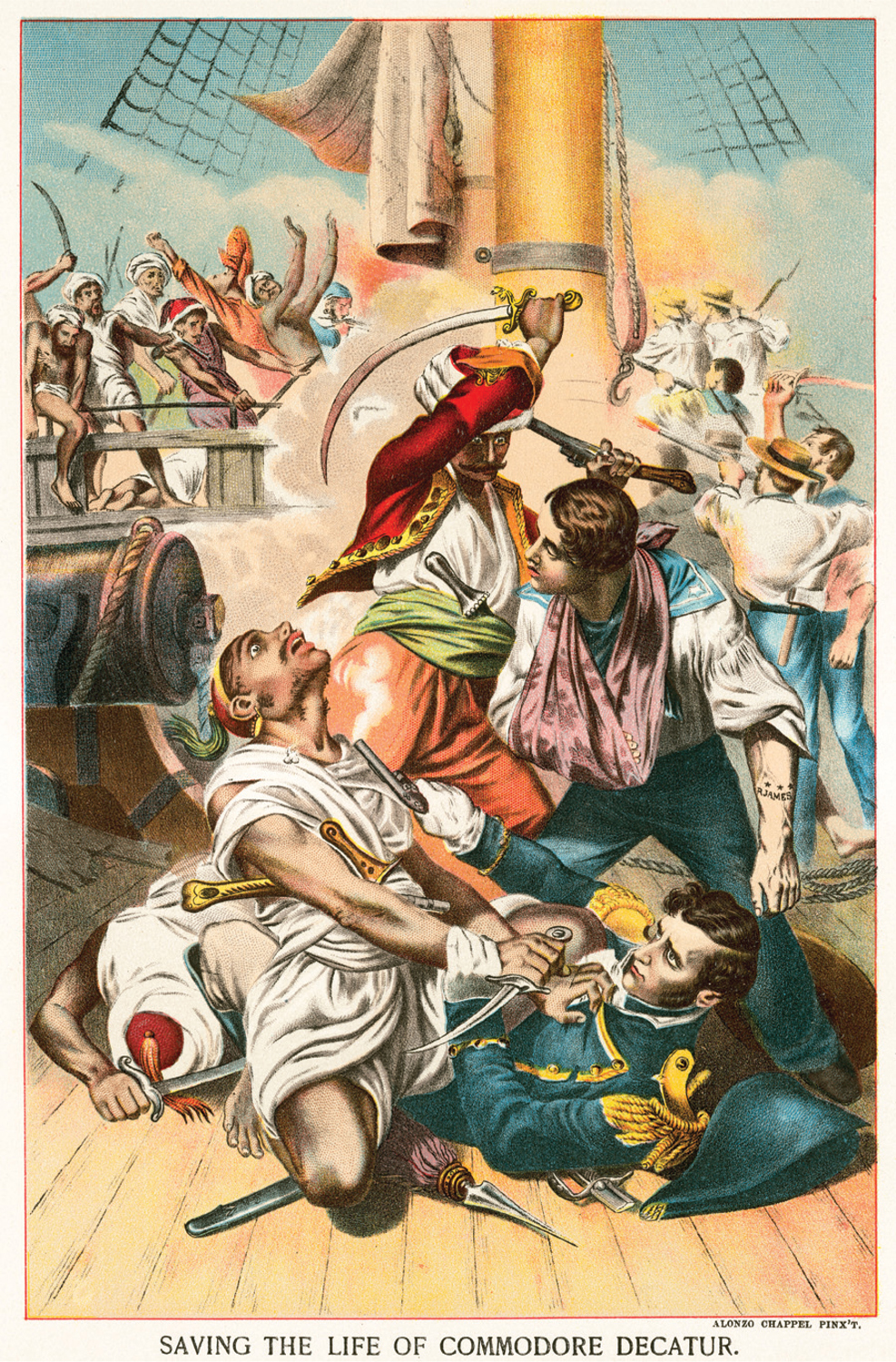

In May 1801, when the monarch of Tripoli failed to secure a large increase in his tribute, he declared war on the United States. Jefferson considered such payments extortion, and he sent four warships to the Mediterranean to protect U.S. shipping. From 1801 to 1803, U.S. frigates engaged in skirmishes with north African privateers.

Then, in late 1803, the USS Philadelphia ran aground near Tripoli’s harbor and was captured along with its 300-

In 1805, William Eaton, an American officer stationed in Tunis, requested a thousand Marines to invade Tripoli, but Secretary of State James Madison rejected the plan. On his own, Eaton assembled a force of four hundred men (mostly Greek and Egyptian mercenaries plus eight Marines) and marched them over five hundred miles of desert for a surprise attack on Tripoli’s second-

Periodic attacks by Algiers and Tunis continued to plague American ships during Jefferson’s second term of office and into his successor’s. This Second Barbary War ended in 1815 when the hero of 1804, Stephen Decatur, now a captain, arrived on the northern coast of Africa with a fleet of twenty-

REVIEW How did Jefferson’s views of the role of the federal government differ from those of his predecessors?